When far-flung, oriental Japanese arts and crafts reached British shores, they attracted attention and were widely sought after. In the diplomatic links of the United Kingdom, Japanese artworks have also become an important bridge for cultural exchanges. Recently, the exhibition "Japan: Court and Culture" was held at the Queen's Gallery, Buckingham Palace, UK. It presented Japanese artworks collected by the British royal family, including lacquerware, porcelain, screens, samurai armor, etc., telling the story of the 300-year history of diplomacy, art and Japan between the UK and Japan. Cultural exchange stories.

In 1881, two young British princes served as midshipmen in the Royal Navy. They came to Japan for a visit and met with the Emperor of Japan. This meeting is not the most important and extravagant one between the British and Japanese royal families, but it is a symbol of the long-term and complex interaction between the two countries. The two princes bought metal teapots and cups at the Japanese market as gifts for their father. During their time in Japan, the two princes were 16 and 17 years old. They got tattoos on their arms, Prince Albert got a couple of storks, and Prince George, the future George V, got dragons and tigers.

"Tattoos were part of naval culture, an aristocratic fashion in late 19th century Britain," says Rachel Rachel, curator of Japan: Court and Culture, a new exhibition recently opened at the Queen's Gallery at Buckingham Palace. Rachel Peat explained. “Tattoos have very different connotations in Japan. Tattoos are a respected art form, but at the same time they are illegal in Japanese history, giving them a sense of mystery and danger. That’s why it attracts tourists. reason."

Curator Pitt said, “Usually, these objects are scattered across 15 different historical periods and royal residences. It is important to bring them together this time and to see them as a whole. Some of the objects It was a gift directly commissioned by the British royal family to Japanese artists, and in some cases some objects were even designed by the former themselves. The result is a work of art at its finest, while revealing a fascinating history, not only of the court There is also the changing relationship between cultural exchanges. Among them, there are both peaks and valleys.”

(This article is compiled from The Guardian, and some relevant content is integrated from the official website of the Royal Collection Trust)

In 1881, two young British princes served as midshipmen in the Royal Navy. They came to Japan for a visit and met with the Emperor of Japan. This meeting is not the most important and extravagant one between the British and Japanese royal families, but it is a symbol of the long-term and complex interaction between the two countries. The two princes bought metal teapots and cups at the Japanese market as gifts for their father. During their time in Japan, the two princes were 16 and 17 years old. They got tattoos on their arms, Prince Albert got a couple of storks, and Prince George, the future George V, got dragons and tigers.

"Tattoos were part of naval culture, an aristocratic fashion in late 19th century Britain," says Rachel Rachel, curator of Japan: Court and Culture, a new exhibition recently opened at the Queen's Gallery at Buckingham Palace. Rachel Peat explained. “Tattoos have very different connotations in Japan. Tattoos are a respected art form, but at the same time they are illegal in Japanese history, giving them a sense of mystery and danger. That’s why it attracts tourists. reason."

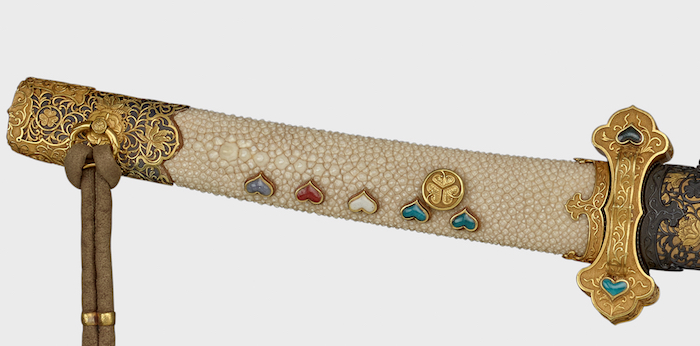

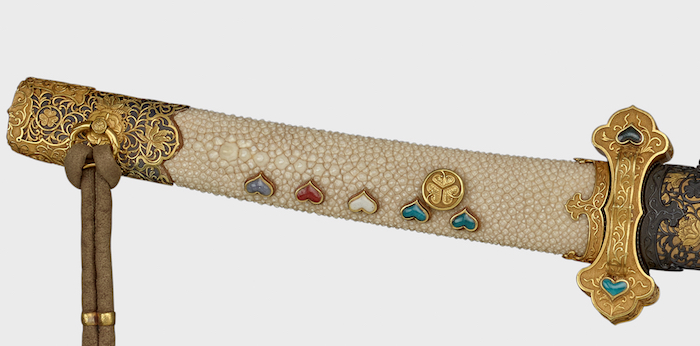

Japanese sword and scabbard

Early 20th century Japanese vase designed by potter Keida Masatarō

Distant, desirable, and inaccessible feelings have always been key to Westerners' fascination with Japanese art, culture, and objects. As proof of this, the exhibition is the first to exclusively showcase works of art from Japan from the British Royal Collection. The Queen's Gallery has also been redesigned. Although the exhibition is not a comprehensive examination of Japanese art (there is no calligraphy in the exhibit, nor is there a display of Japanese kimonos), a story of diplomacy, taste and power is revealed through these artworks and crafts.

Ceramics of Japanese Female Figures, 1690-1730

Japanese ceramics

The first contact between the two royal families was in 1613, when the twins exchanged gifts, among which, the British royal family received a set of samurai armor. This happened before Japan closed its doors to the West. In the 200 years since, it is not that Japanese artifacts have lost their appeal in the West. Japan's isolation and isolation also made the secrets of craftsmanship hidden from Westerners. This also makes Japanese handicrafts more fashionable and sought after. Through Chinese and Dutch merchants, the British royal family continued its collection of porcelain and lacquerware. In the 19th century, Japan reopened to the outside world, which also prompted the re-visit of the British royal family. So far, the West has gained a new appreciation and understanding of Japanese art. At the beginning of the 20th century, the relationship between Britain and Japan was harmonious. During World War II, the relationship between the two countries broke down. In the 1950s, Emperor Hirohito's coronation gift to Britain's new queen healed relations between the two countries, a move widely seen as an artistic symbol of a new era of collaboration.Curator Pitt said, “Usually, these objects are scattered across 15 different historical periods and royal residences. It is important to bring them together this time and to see them as a whole. Some of the objects It was a gift directly commissioned by the British royal family to Japanese artists, and in some cases some objects were even designed by the former themselves. The result is a work of art at its finest, while revealing a fascinating history, not only of the court There is also the changing relationship between cultural exchanges. Among them, there are both peaks and valleys.”

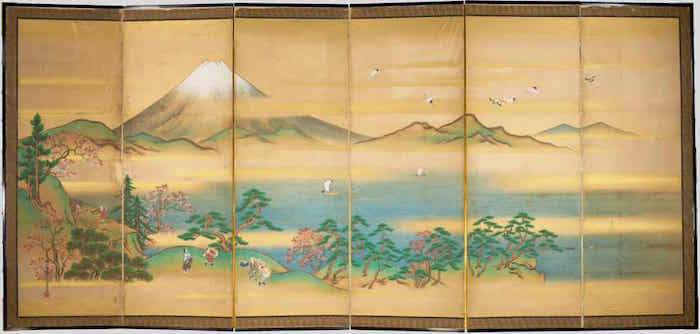

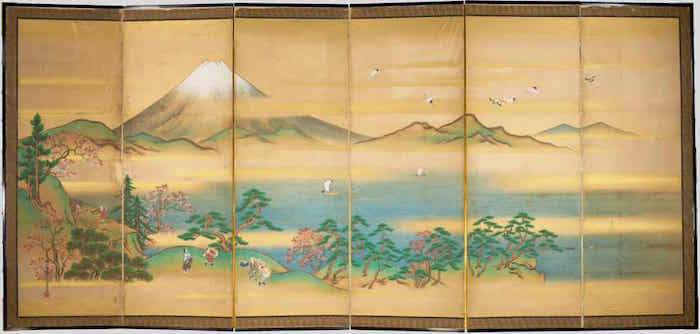

Folding screen created in 1860.

This painting depicting Mount Fuji in spring was given to Queen Victoria by the Japanese royal family in 1860. This is a pair of paintings, and this exhibition is one of them. The painting was thought to have been lost, but was rediscovered in preparation for this exhibition. The heart of this piece is embroidered on silk and the folds are made of gold leaf, which is very fragile. The screen is considered a painting, not a practical piece of furniture. When it comes to showing, opening the show can best showcase the artist's artistic prowess. The piece is also one of Japan's first diplomatic gifts after more than 200 years of isolation and reopening to the world. Afterwards, the Japanese royal family purchased this silk screen from Nishimura, Iida and Kawashima in Kyoto in the 1880s, both to decorate the new Imperial Palace in Tokyo, which was completed in 1889, and as a diplomatic gift to foreign envoys.

Japanese fan, 1880

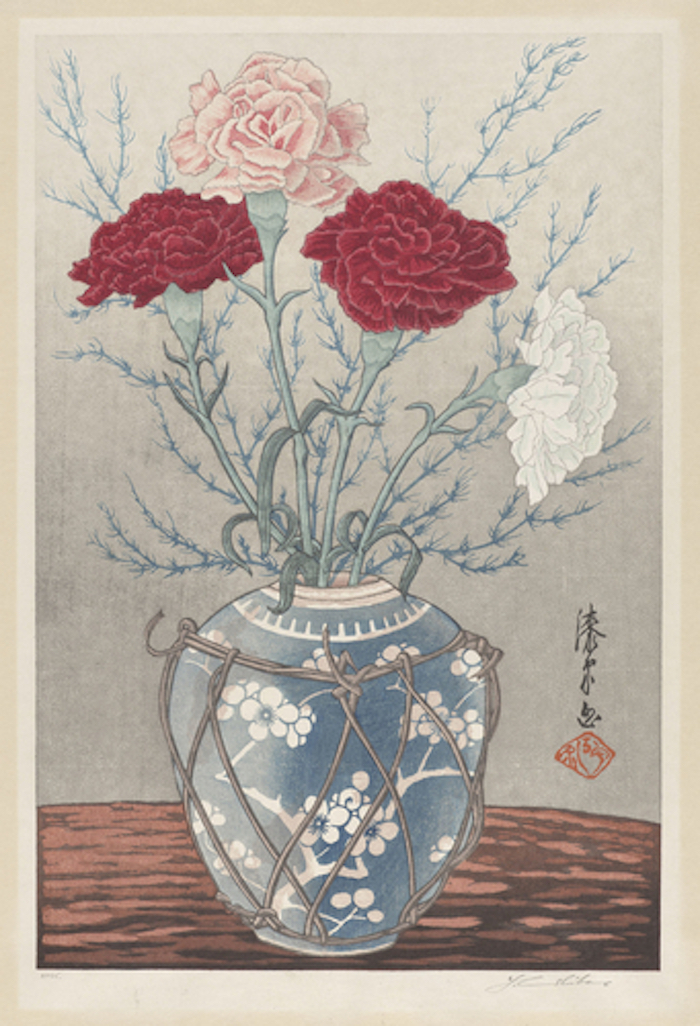

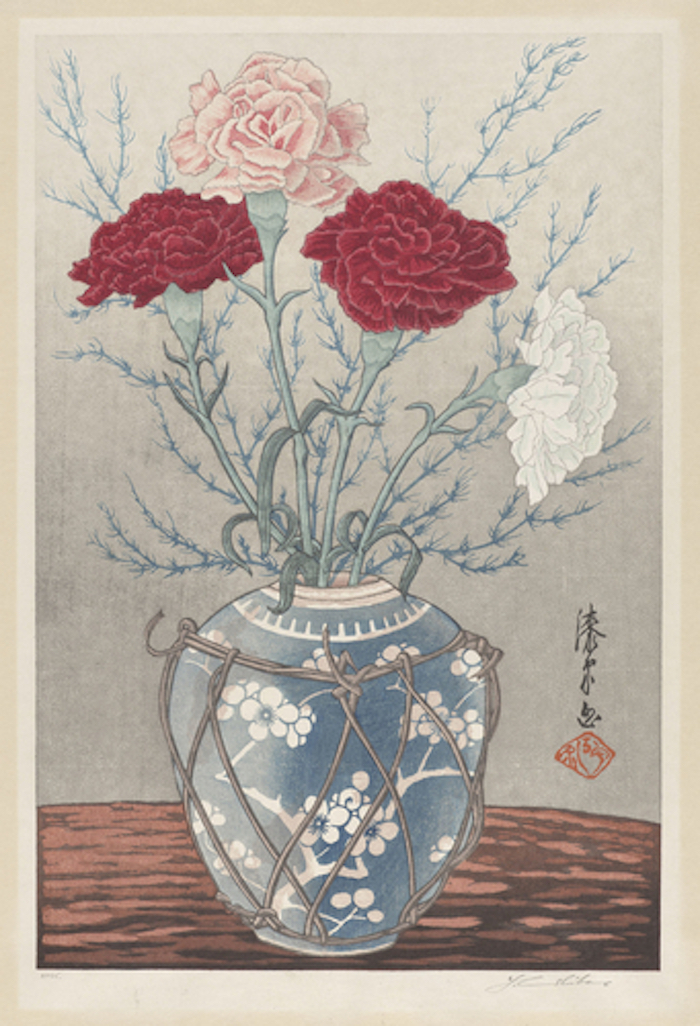

Ukiyo-e print depicting carnations

For centuries, Japan has used paper and ink to create colorful woodblock prints known as "ukiyo-e". This type of painting depicts folk customs, songstresses, flowers and plants, and landscapes in various places. The above image of carnations is presented in a five-color overprint.

Pair of porcelain incense burners in the form of rabbits, 1680-1720

Japan has been producing ceramics since the Jomon period. From the 1640s, the works of Japanese potters were admired in Europe for their harmonious colors. The decorative porcelain pictured above represents the Year of the Rabbit. The artist also draws on broader Eastern mythology, the concept of rabbits, the moon and immortality. At the same time, the china served as an incense burner, allowing smoke to emerge from the hole in the stump where the rabbit sat.

Samurai Armor, 1537–1850

This samurai armor is made of leather, deerskin, horsehair, bear mane, gilded copper, gold wire and thousands of small iron pieces. These iron sheets are combined with bright blue and red silks to form a flexible covering that wraps around the body. At the same time, this samurai armor is likely made using elements from multiple sets of armor. In 1869, the Japanese royal family gifted it to Queen Victoria's son Alfred, the first overseas royal to visit modern-day Japan.

Wendell Halt's portrait of Prince Alfred

box inlaid with fritillary

In the 16th century, the sparkling box was one of the first Japanese exports to Europe. This kind of box is almost inlaid with thick fritillary to the surface. The style is called "Nanban" in Japan because it appeals to Western buyers who arrive on the islands from the south.

Cosmetic box by Matsuya Shirayama, 1890–1905

Decorated with black, gold and silver lacquer, this wooden cosmetic box was the first diplomatic gift after World War II. In 1953, on the occasion of the coronation of the Queen of England, it was hereby presented by the Emperor Shōwa of Japan. This object was made by Shirayama Shōsai, one of the leading artists of the golden age of Japanese lacquerware in the early 20th century. Here he depicts a heron and paints its feathers in silver paint with golden stripes.

Gift Boxes

Box for writing instruments, late 18th-early 19th century

Japanese screen

The exhibition will be on view until March 12, 2023.(This article is compiled from The Guardian, and some relevant content is integrated from the official website of the Royal Collection Trust)

Related Posts