In the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang, the paintings depicting the story of "Subduing the Demon" or "Laodu Chadousheng" brought together a very rich and diverse material, including at least 20 murals, a scroll of Bianwen paintings, a fragment of a painting banner and some The era of line drawing and white painting also lasted for hundreds of years, from the 6th century to the 10th century or even later. These materials allow us to deeply explore the spatial composition in Dunhuang painting, on the one hand guide us to explore the relationship between painting, text and rap, and on the other hand prompt us to observe the interaction between different pictorial spatial modes.

The entire Conqueror story consists of two loosely connected parts. The first part tells the story of the creation of Gion, the sacred place of Buddhism. In the second part of the story, the plot has changed dramatically, with the emergence of two opposing core characters-the Buddhist Shariputra and the outsider Laoducha, as well as a new narrative theme-the two fight through illusions to compete.

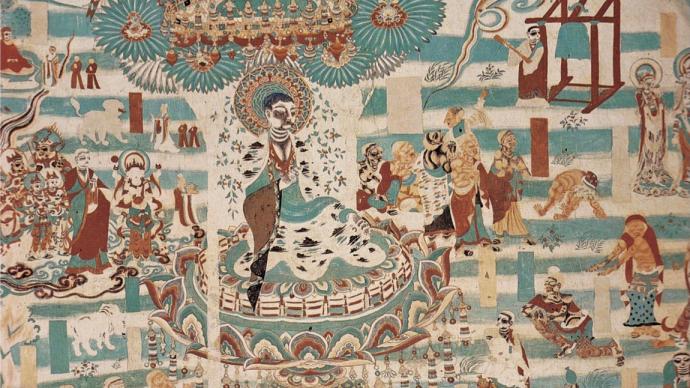

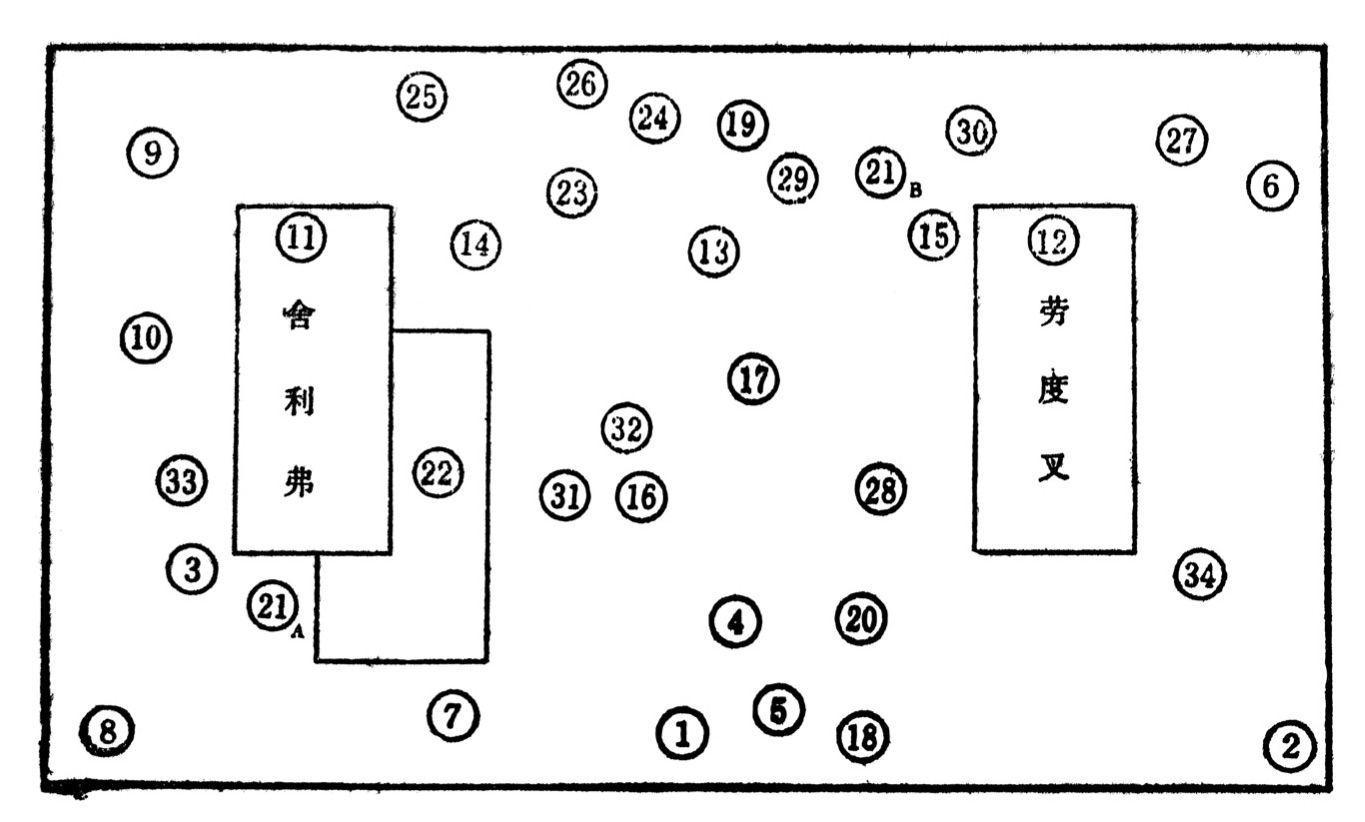

Figure 1: The fresco of "Subduing the Demons", Cave 12 of the West Thousand Buddha Caves, mid-6th century

The above summary is based on an earlier version of the story of "subduing the devil" titled "Suda Qi Jingshe", which is found in the classic "Xianyu Jing". The Classic of the Wise and the foolish is not a Buddhist scripture in the conventional sense, but a collection of Buddhist stories compiled after eight Chinese monks went to Khotan to attend a large Buddhist gathering. After the collection spread to Turpan, it was brought to Liangzhou by monk Huilang in 435, and the current title was added. This version immediately provided the basis for subsequent literary and artistic creations, including the much more complicated "subduing the devil" script found in the Tibetan scripture cave.Emergence of binary pictorial space

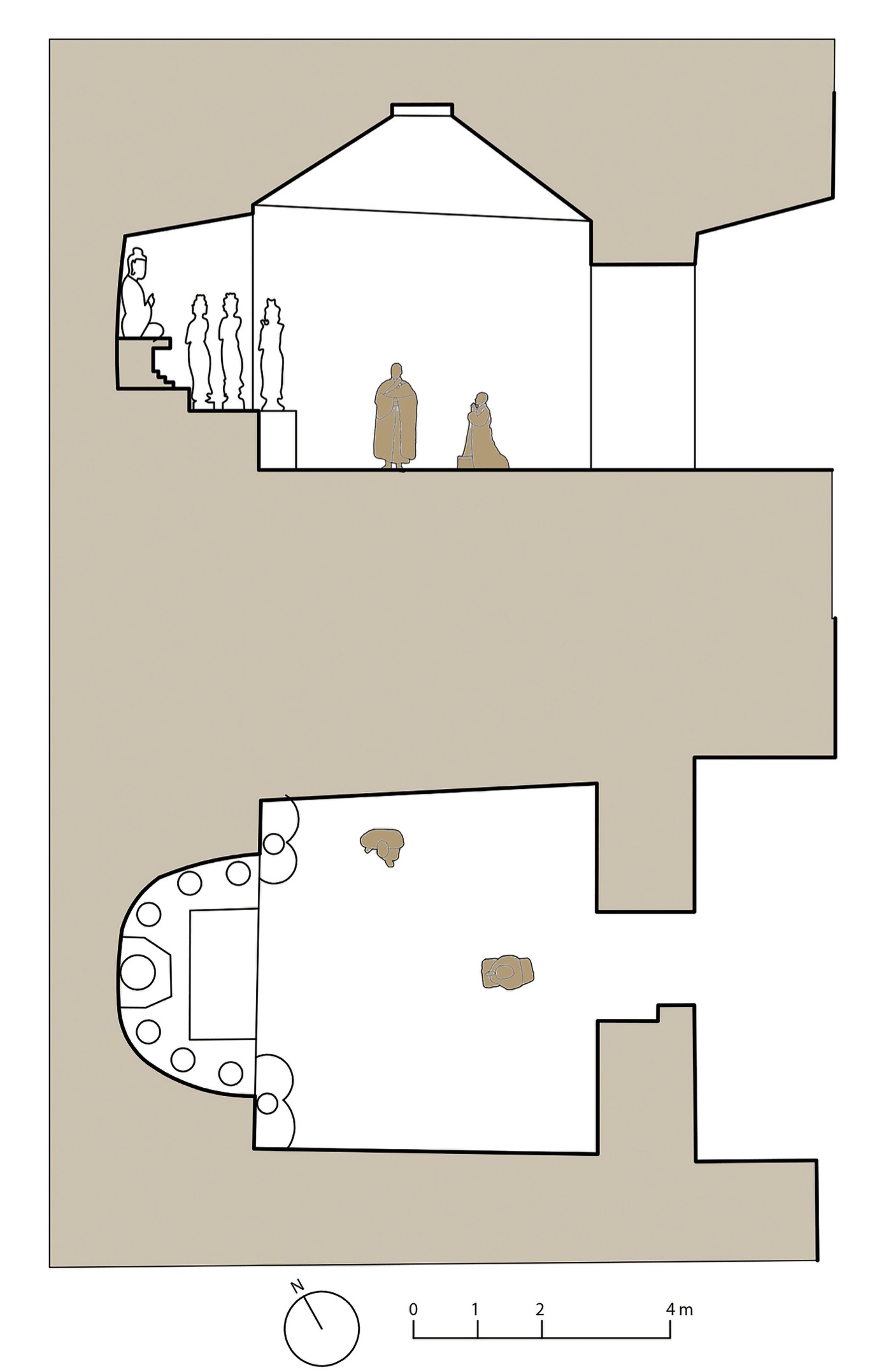

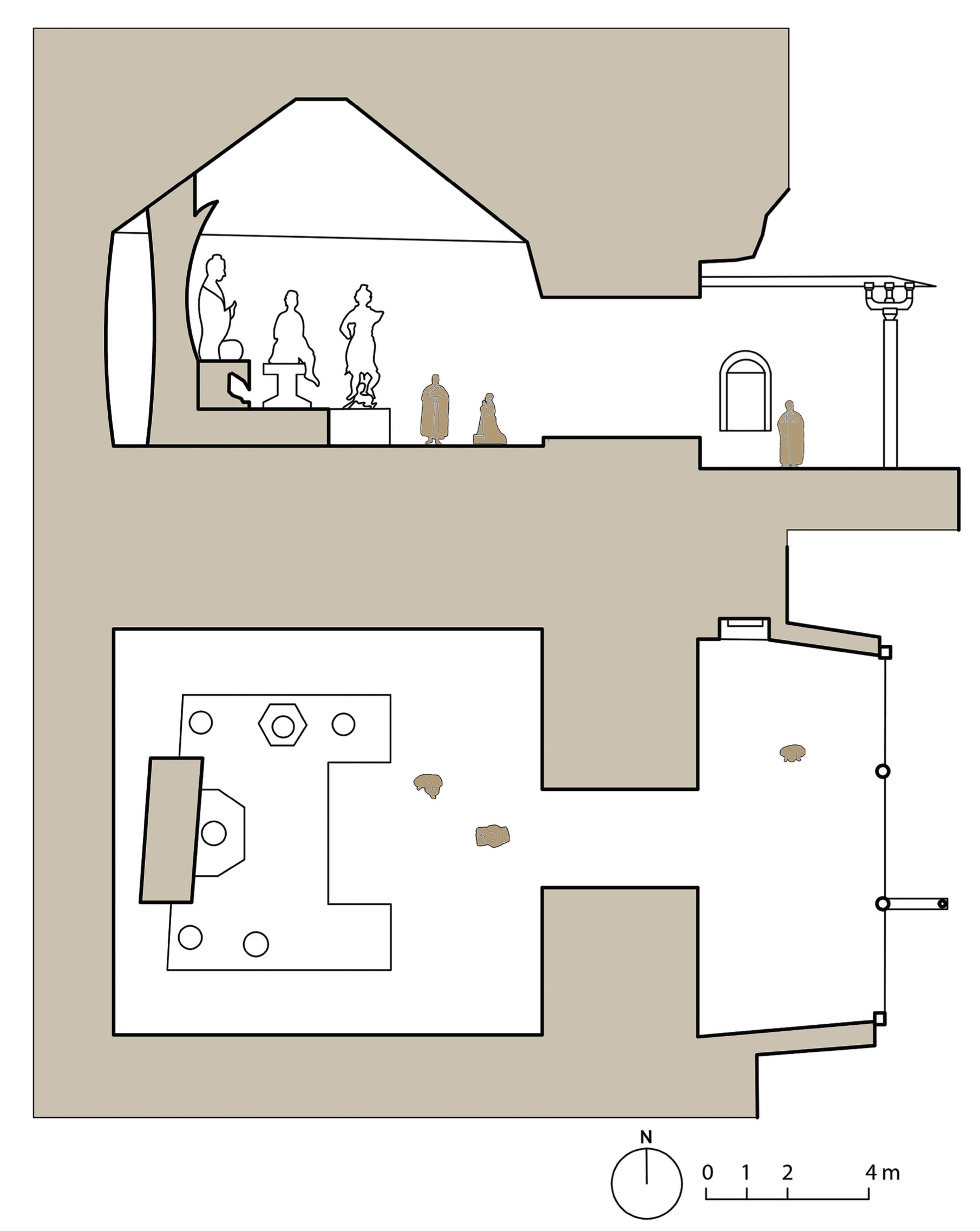

Figure 2: Elevation and plan of Cave 335, painted by Zhou Zhenru

If the earliest murals of "Conquering the Demons" imitated the linear literary narrative mode, the subsequent murals of the same theme in the Mogao Grottoes contradicted the literary prototype, and constructed a new visual representation of the story in a non-linear "binary" way. space frame. This fresco—comprising two sets of pictures that echo each other—is located in Cave 335 of the Mogao Grottoes and, according to an inscription on the north wall, was built in 686 and belongs to the early Tang Dynasty (Fig. 2). There is a large rectangular Buddhist niche on the west wall (the rear wall) of the cave. In the center of the niche, there is a Buddha statue, and there were original disciples and Bodhisattva statues on both sides. Now all but one has disappeared, leaving only a vague figure on the niche wall ( image 3). Clouds and clouds rose up along the two sides of the Buddha's backlight and went straight to the top of the cave. In the clouds appeared the Duobao Pagoda, and the two Buddhas, Shakyamuni and Duobao, sat side by side (Figure 4). The story of "Conquering the Devil" is painted on the walls on both sides of the niche, and its spatial structure and narrative style are very different from the 6th century murals in the West Thousand Buddha Caves.

Figure 3: Buddhist shrines in Cave 335

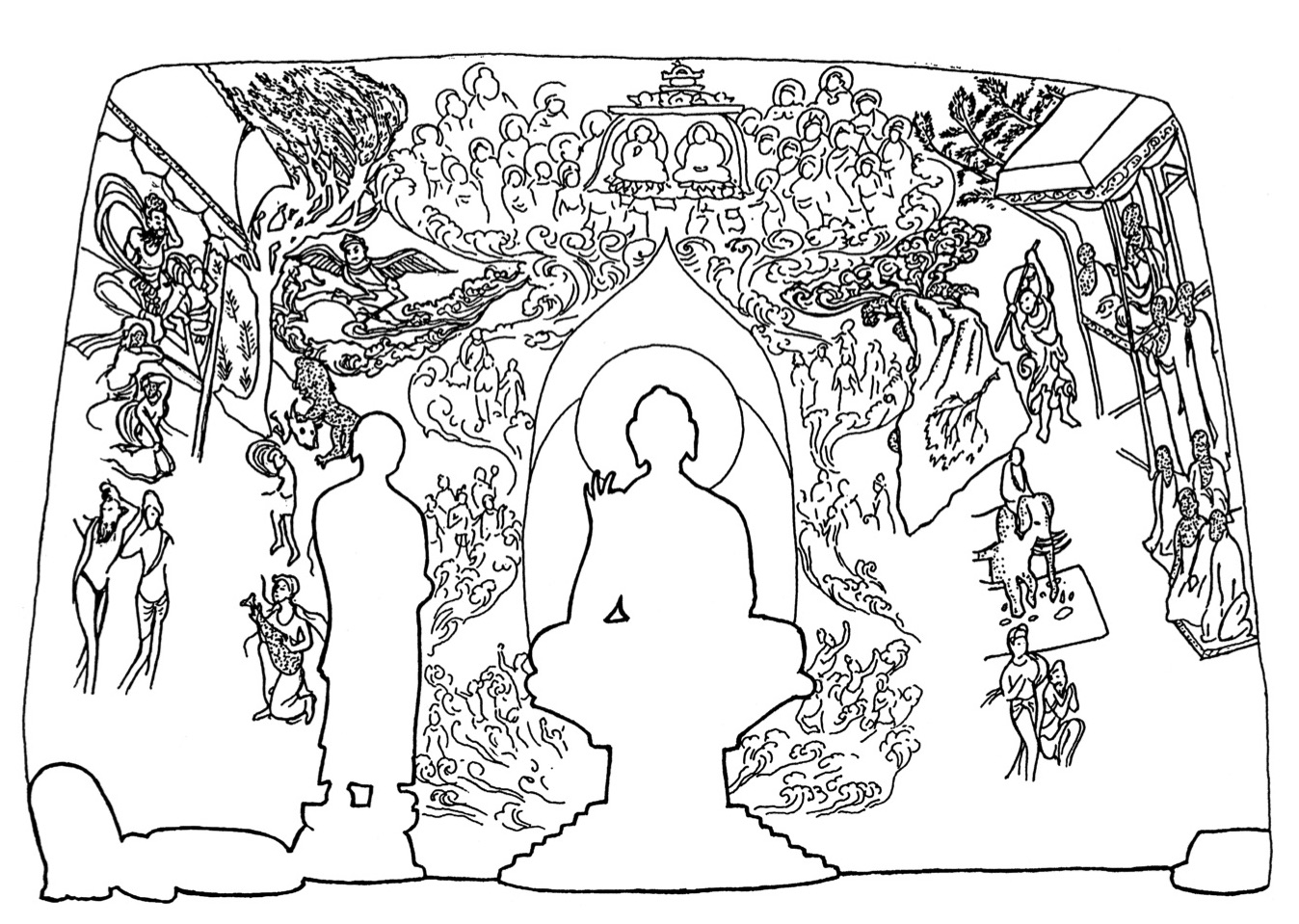

Figure 4: The shrine on the west wall of Cave 335, painted by Wu Hung

An important change made by the late 7th-century painter who created this fresco is the complete omission of the first part of the story: there is no scene of Suda looking for Gion, all the plot is taken from the fight between Sariputta and Lauducha . Therefore, this painting can no longer be titled "Sudaqi Jingshe", but can only be called "Saving the Demon" or "Laodu Chadousheng" - this is also what this type of mural was used in the Tang and Song painting classics name. Since all literary versions of this story—both scriptures and later versions—include the "Suda Qijingshe" part, and never one that focuses solely on fighting methods, it is reasonable to assume that this new emphasis has arisen In the field of visual arts, the frescoes in Cave 335 provide important evidence for this hypothesis.This new narrative emphasis is closely related to the spatial pattern of frescoes, which I call "dual structure" or "opposition structure". Different from the "idol-shaped" scripture paintings centered on Buddha or Bodhisattva, the "dual structure" always contains two figures side by side, in the midst of debate or struggle. They constitute the double center of the pictorial space, and other characters and plots are arranged around them as secondary factors. The frescoes in Cave 335 represent the initial form of this spatial pattern—although belonging to the shrine centered on the Buddha, it is divided into two sets of images facing left and right. A group appeared on the north wall of the niche, with Shariputra sitting under the canopy as the core, surrounded by several monks. On the opposite south wall, Lauducha, which is crowded with men and women outsiders, is being hit by a hurricane. There are fighting plots scattered between these two groups of characters: near Shariputra, the King Kong fighter strikes the mountain, and the white elephant sucks up the pool; near Laoducha, the Garuda defeats the poisonous dragon, the lion swallows the buffalo, and the hurricane blows down the tree. The plot of the battle between King Bishamon and the evil ghost is not seen here-maybe because the image of the evil ghost is not suitable to appear in the Buddhist altar, or the scene of Laoducha taking refuge in the Buddha Dharma added on the right has achieved a formal balance in the picture space.

Fig. 5: Early frescoes of "Vimalakirti", Cave 420, late 6th century

Separated by the Buddha statue in the center of the niche and the backlight, the two sets of images are not connected in a linear sequence and thus cannot be viewed as a continuous narrative painting. Their spatial symmetry—or, more properly, the spatial opposition of the two—shows as an "abstract" or "condensation" of Sariputta and Lauducha's several battles. In order to highlight the theme of "opposition", the painter follows a completely different logic from the previous mural of "Conquering the Devil". The early Tang painter in Cave 335 completely departed from this logic: his design process started with two competing characters, extracted them from the story, placed them in relative spatial positions, and then filled in this symmetrical pattern. into a solo fight scene. Therefore, if the 6th century frescoes are linear and temporal, this early Tang fresco is dualistic and spatial. The difference between the two is so great that it is hard to imagine that the latter developed from the former, but it is more likely that a certain fresco that already existed in the Mogao Grottoes provided the painter with a pictorial space model. This hypothesis draws our attention to the images showing the fighting between Vimalakirti and Manjushri—the only work in Dunhuang frescoes in the early Tang Dynasty with a clear “dualistic” spatial structure.

Figure 6: The right half of the fresco "Conquering the Demons" in Cave 335, photographed by Pelliot in 1908

There are a total of 58 frescoes in the Mogao Grottoes, which were produced in the long-term development process from the 6th century to the 11th century. The "Vimalakirti Sutra" tells that the Buddha ordered his disciples to visit the lay Buddhist monk Vimalakirti. Manjushri was finally appointed to undertake this mission, but as expected, he immediately fell into a debate with the famous orator-Vimalakirti's illusion A variety of heart failures detect Manjusri's perseverance and mind. It is not difficult to see that this debate has much in common with the story of "Conquering the Devil": both have a pair of "dual" antagonists, and they also have numerous scenes of magical betrayals. These commonalities can explain the similarity between the portraits of "Vimalakirti" and "Conquering Demons", and also explain why the two types of murals in the Mogao Grottoes have been painted in similar positions and have the same composition style since the early Tang Dynasty. Development continued for four centuries.This 7th-century mural in Cave 335 is important to the development of Dunhuang art in two aspects. One is that its "operating location" method has become the blueprint for all subsequent large-scale murals of "Conquering the Devil"; The rap show offers new plot and vocabulary.

Combination of Linear Space and Binary Space

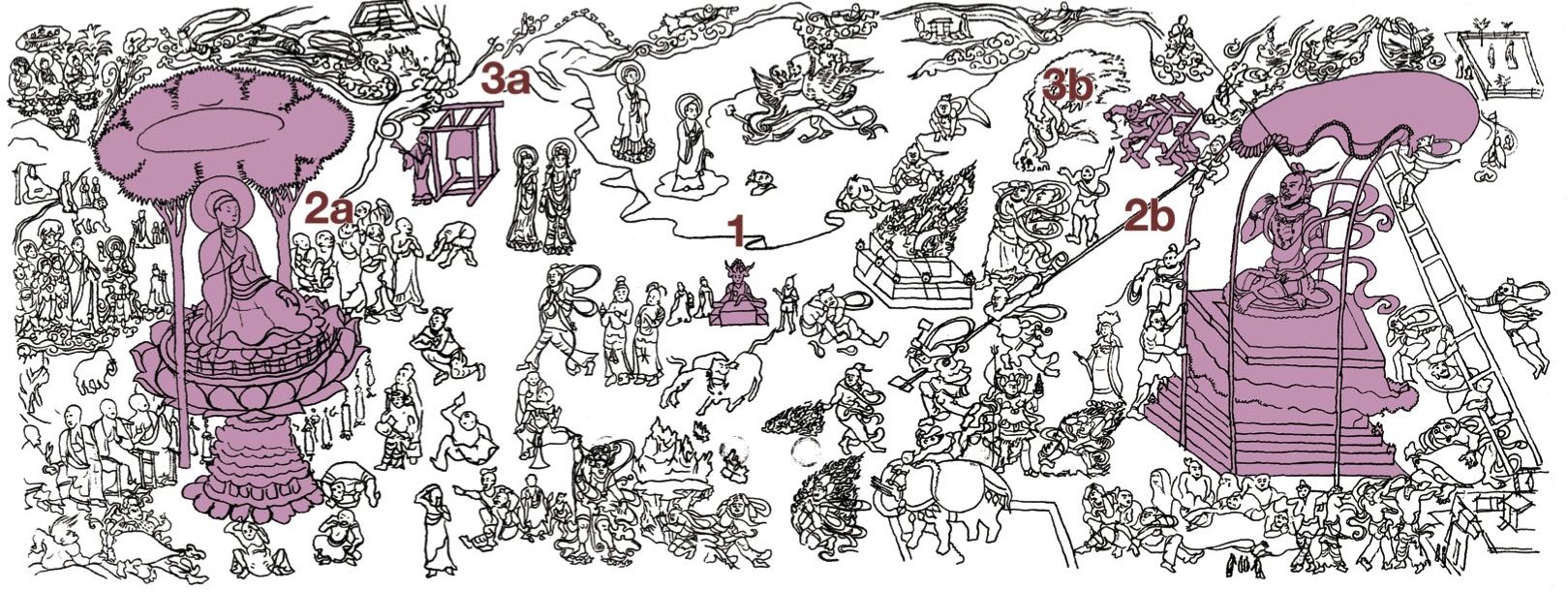

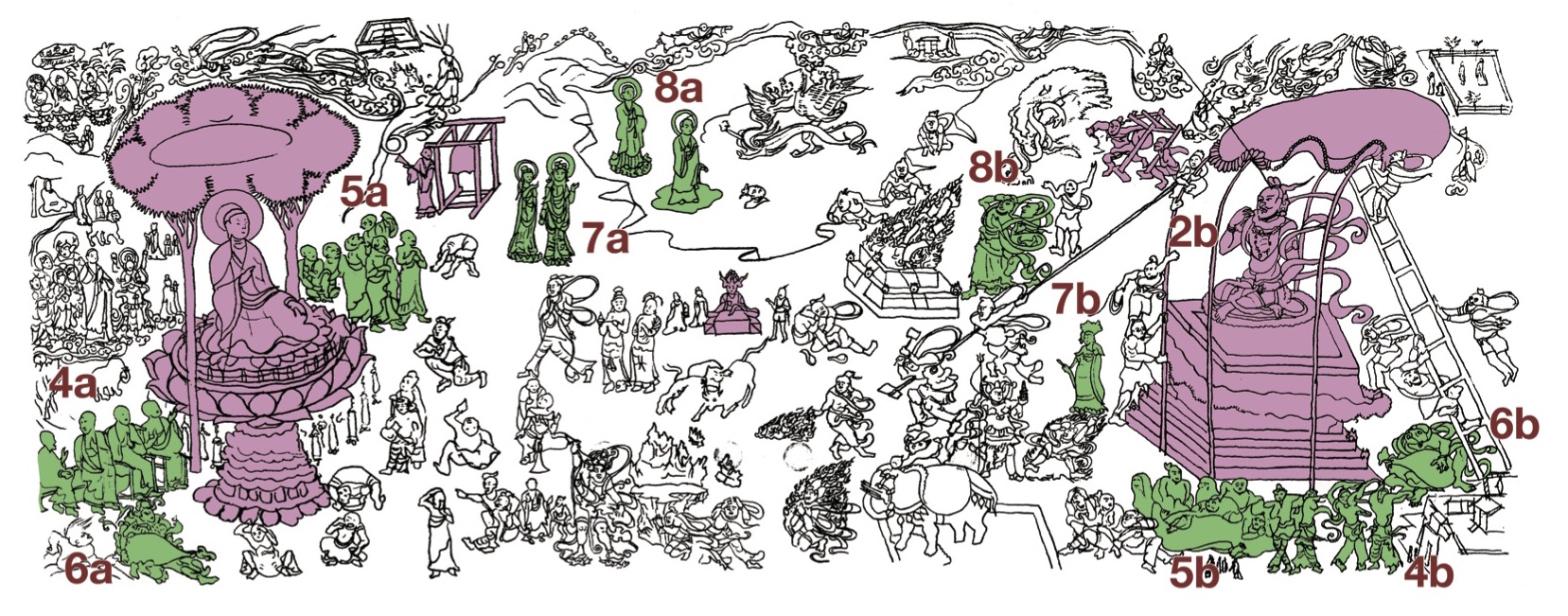

Before the middle of the 8th century, there were at least two literary versions of the story of "Saying the Demons" ("The Book of Wise and Foolish" and "Conquering the Demons") and two modes of painting representation (the murals in the 6th and 7th centuries). Since then, the pictorial representation of this subject has continued to develop along two different lines. On the one hand, there is a picture scroll directly used for speaking and singing in Dunhuang, which reflects the revival and complication of linear narrative techniques. On the other hand, at least 18 large-scale frescoes continued the binary pattern established by the frescoes of the early Tang Dynasty, and developed them into independent paintings of "Conquering the Demons". These two traditions are not entirely independent and unaffected by each other: on the one hand, the Bianwen Painting Scroll combines the binary composition into a temporal linear narrative; to enrich itself. This section focuses on the former aspect, the development shown in the well-known scroll of Conquering the Demons and Bianwen. The next section focuses on how the disguised murals absorb the plot of the text to enrich the spatial "opposition" composition.

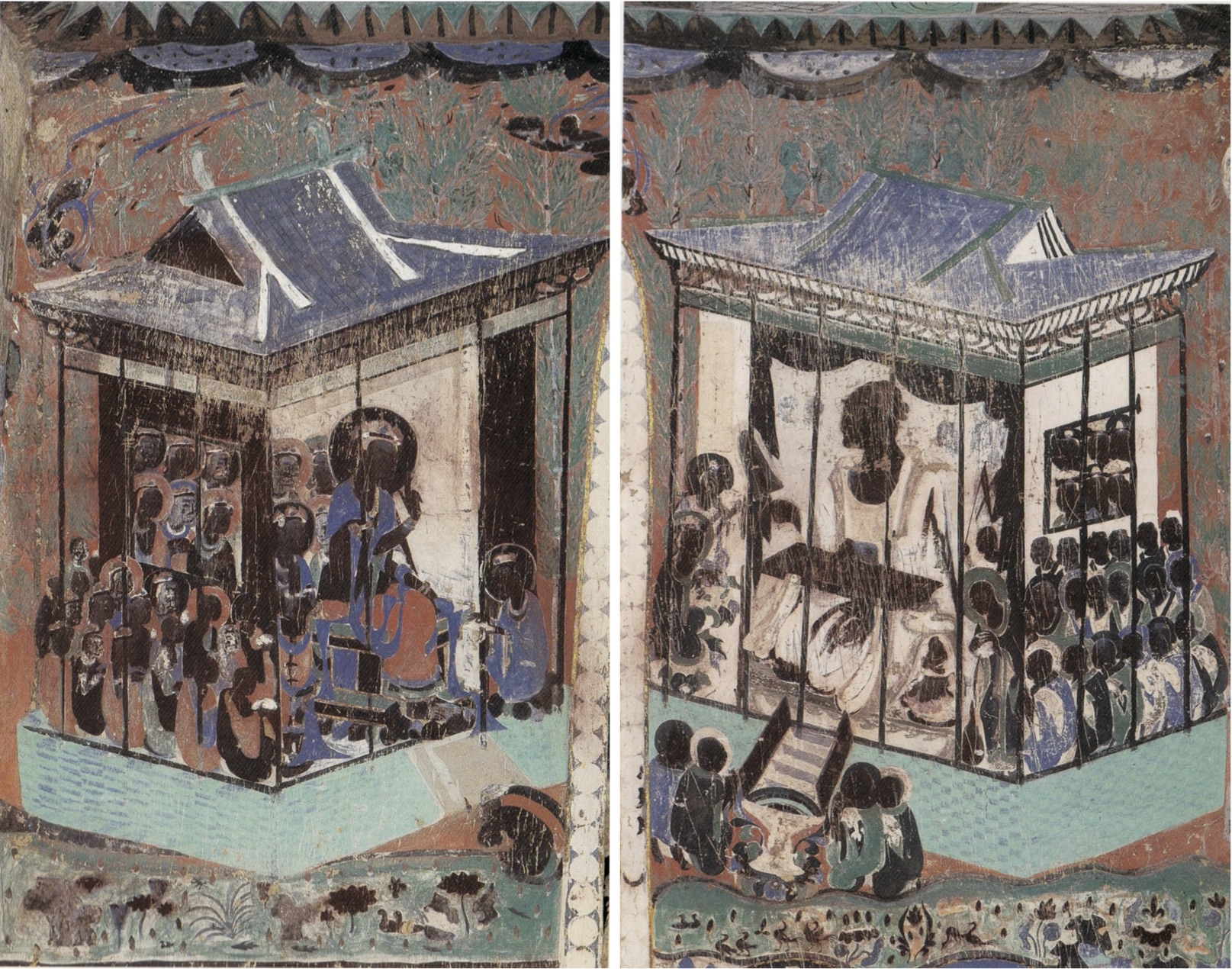

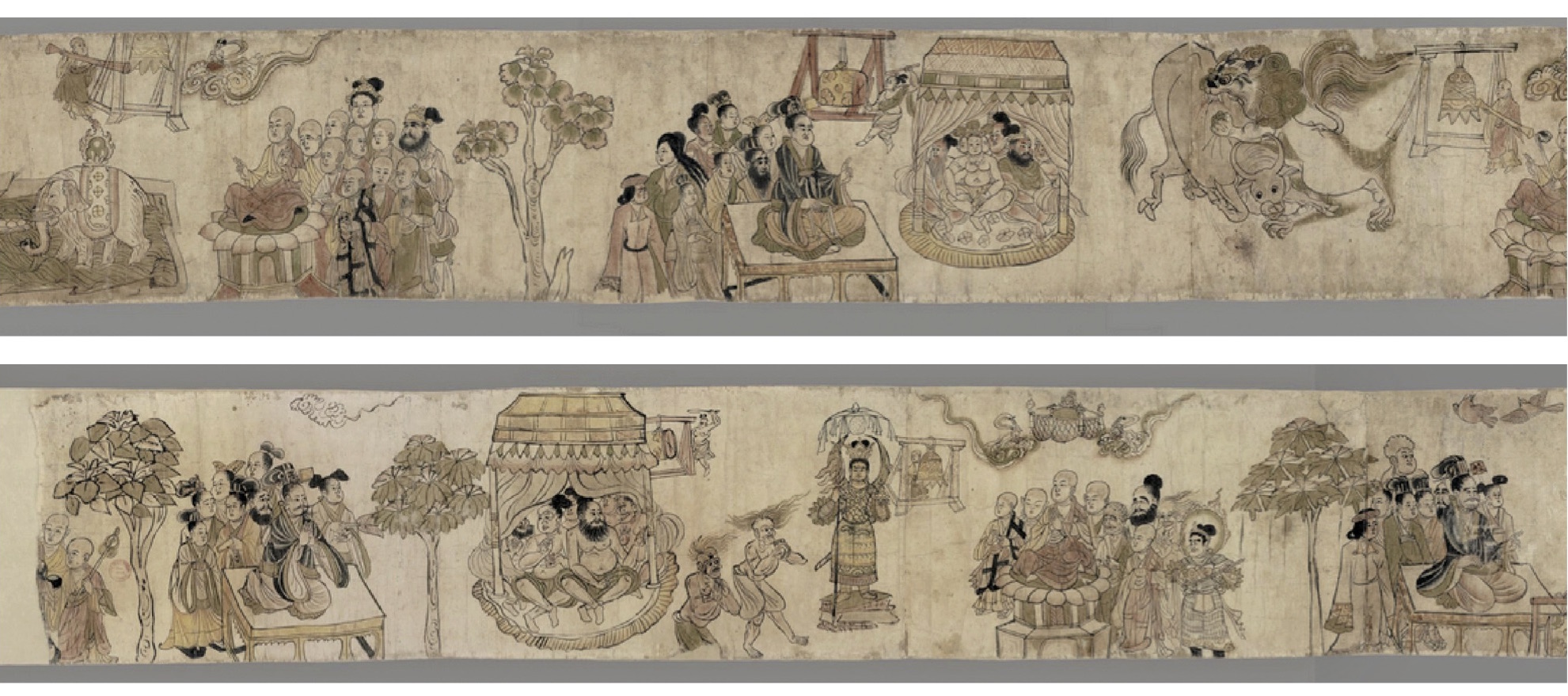

Figure 7: Scroll of the 8th century, "Conquering the Demons", in the collection of the National Library of France

The scroll was found in the Dunhuang Book Collection Cave, and was brought to Paris by Pelliot. It is now in the National Library of France, numbered P.4524 (Fig. 7). It has been discussed by many scholars over the past forty years and is dated to the 8th to 9th centuries. The picture scroll is made up of 12 sheets of paper linked together. Although the beginning and end parts are broken, it is still 571.3 cm long. The content about "Sudaqi Jingshe" is completely missing, and the long scroll only depicts the six fights between Shariputra and Laoducha. In this way, this work combines two previous frescoes of "destroying the devil": in general form, it arranges several pictures in a linear horizontal strip, so it is similar to the 6th century frescoes in the West Thousand Buddha Caves. But in terms of content, it follows the tradition of the frescoes in Cave 335 of the Mogao Grottoes, and only depicts the part of fighting.

Figure 8: Detail of the scroll of Conquer the Demons, showing some of the characters in the Dou Fa audience turning their heads towards the next scene

Figure 9: Detail of Gu Hongzhong's "Han Xizai Night Banquet", 12th century facsimile

This fusion is more evident in the spatial composition of the picture scroll. For example, in the 6th century frescoes, the painter internally divided this super-long picture, and composed the entire narrative with several pictures like the "frames" of a movie. As in the 6th century frescoes, the painter also used landscape elements to divide these frames: the trees that appear constantly in the painting are not directly related to the content of the story, their function is to divide the painting into six parts, each part showing a fighting method. Other details reflect the artist's more delicate compositional techniques, such as one or two figures at the end of each section turning their heads to face the next scene (Fig. 8). We need to remember that the "next scene" has not yet been opened, and the role of these characters is therefore to make the audience look forward to the part that will unfold. Some famous paintings in the history of Chinese art also used this technique. For example, in the painting "Han Xizai Night Banquet" painted in the 10th century, the painter Gu Hongzhong skillfully used a series of vertical screens to divide the scrolls into several spaces to display a series of paintings. Festive activities. He goes on to use secondary characters to link these separate spaces into a whole - most notably between the last two spaces, a young woman talks to a man through a screen, inviting him to enter behind the screen space to go (Figure 9).

Figure 10: Detail of the scroll of "Conquering the Demons and Bianwen", showing a fighting plot

Therefore, on the whole, the painting scroll of Conquering the Demons and Bianwen inherits the tradition of the 6th century frescoes, showing the sequence of different events in a linear space pattern, but each frame in the scroll adopts the dual structure and the 7th century frescoes. Symmetrical composition, with Buddhists on the right and outsiders on the left (Figure 10). This symmetry is enhanced by the contrasting figures of the two groups of competitors: bald Buddhists in cassocks, half-naked with bushy beards; Shariputra seated on a circular rosette; Under a square tent. Each scene is accompanied by a bell and a drum, which is obviously from a passage in Bianwen: "There are two paths to victory and defeat, and each must be clearly recorded. When a monk wins, he beats the golden drum and gets down the golden chip; if the Buddhist is strong, he deducts the golden bell and points it. Shangzi." The painter chose this pair of musical instruments from the hundreds of objects mentioned in the Bianwen, no doubt because their symmetrical images and functions can further strengthen the dual structure of the overall picture. In fact, with the exception of the king and his subordinates as judges, the other images in the scroll appear in pairs: the Buddhists and the outsiders sit opposite each other, their illusions fighting each other, and the drums and bells face each other. When this binary composition is repeated by the unfolding of the long scroll, the spatial narrative condensed in the frescoes of Cave 335 unfolds continuously in front of the audience in a linear fashion. Scholars all agree that this Bianwen picture scroll—also known as "disguised form scroll" or "biantu"—is an auxiliary prop used when singing Bianwen, but they have different opinions on how to use it. Baihuawen believes: "As for this disguised paper, it is a brief written record for (the narrator) to refer to." This explanation is unconvincing because the text on the back of the paper is not a brief record , but faithfully copied the verse part of the Bianwen describing the six times of fighting. In contrast, another hypothesis put forward by Wang Chongmin is more enlightening: "The front of this volume is a story map, and the lyrics of each story are copied on the opposite side of the back. This further shows that the changing map and the narration are mutually exclusive. Use (pictures can replace white), instructing to change the picture to tell the white, making it easier for the audience to understand. Then sing the lyrics, so that the audience can more happily grasp the main meaning of the story in the beauty of the music." Wang's hypothesis can be derived from This is supported by an observation by American scholar Victor Mair: "If anything is to be written on the paper used for performance, it should be verse. We have known this from the whole Indian rap tradition. In this tradition, the verse is always relatively fixed, while the vernacular part tends to be updated with each sing."

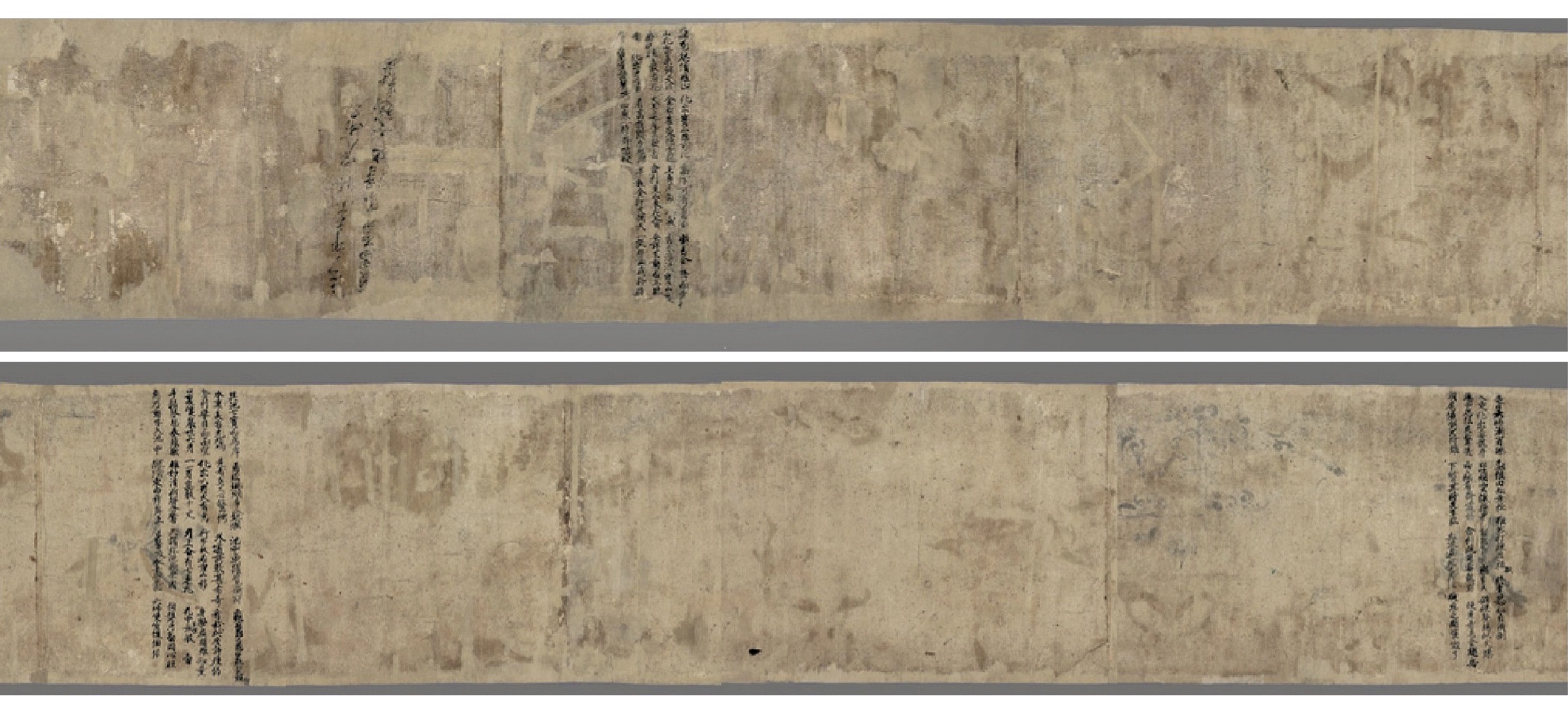

Figure 11: Bianwen lyrics copied from the back of the scroll of "Conquering the Demons and Bianwen"

It seems that these scholars all believed that only one person needed to perform "Conquering the Demons", and he kept showing the picture scroll while telling the story. This situation undoubtedly exists in history, but many clues lead us to imagine that when using this "Sorcerer" scroll, it is likely that two narrators will tell and sing separately. One of the most important clues is the relative position of the picture and the verse. The former appears on the front of the scroll, while the latter is copied on the back of the scroll. Since the ancients always wrote the inscriptions on the painting on the front which can be viewed, this scroll copied the verses at the back, and the space between each paragraph was quite wide, which must have its special purpose (Fig. 11). Another clue is the conventions of Tang Dynasty speech and singing performances. In the "Conquering the Demons and Bianwen" found in the Dunhuang Tibetan Scripture Cave, the vernacular narrative part of each plot always ends with a question sentence "Ruowei", which leads to the following lyrics. The same structure is also found in the scriptures used for "vulgar preaching" found in the Tibetan scripture cave. At that time, the common lectures were generally conducted by two people, "Dharma Master" and "Dujiao". After the Master preached a paragraph, he gave a "How to" prompt to Dujiao, and after Dujiao, he sang the next Buddhist scripture. The popular saying was extremely popular in the Tang Dynasty, and it was not only supported by the royal family, but also welcomed by ordinary people. More than one poet of the Tang Dynasty described the influence of vulgar lectures on the social customs of the time. For example, Yao He said in "Listening to the Monk's Cloud Lectures": "Far and near, hold fast to listen carefully, and there is no one in the wine shop and fish market." Changzhou Yuan Monk wrote: "It is still heard that on the opening day, there are fewer fishing boats on the lake." It is said that when the popular lectures are held, not only the hotels and markets are crowded, but the fishing boats on the lake also mostly disappear.Such a popular mass art form is likely to influence other types of rap performances. Starting from this assumption, we can reconstruct the use of the "Devil" picture scroll as follows. The two storytellers—referred to here as “speakers” and “singers”—perform in concert with each other. The "singer" holds the picture scroll, and the "speaker" stands in front of the picture scroll, pointing to the unfolded picture and telling the plot of the fighting style depicted in it in vernacular. When the "speaker" finished speaking a paragraph, he issued a prompt of "ruowei", and the "singer" then sang the verse copied on the back of the scroll. After singing, he rolled up the picture and unfolded the next scene, while the "speaker" continued to narrate the paragraph in the picture that had just been unfolded. One reason for copying the verse behind the scroll is so that the "singer" will not sing the wrong words, and another reason is to indicate where each scroll will stop. Therefore, each verse is always copied relative to the end of the front image, and the "singer" can know where to stop each time the scroll is unfolded without looking at the front image. That is to say, when he rolled the animation scroll to reveal a verse, what he saw in front of him happened to be a complete picture. The "singer" thus always faces the transcribed lyrics on the back of the scroll, while the "speaker" and the listener always look at the picture on the front of the scroll.

Dual Composition and Spatial Narrative

Zhang Yichao recaptured Dunhuang from the Tubo rule in 848, and the Mogao Grottoes saw an upsurge in the construction of large-scale caves, often decorated with the murals of "Conquering the Demons". Some scholars believe that these frescoes may have political significance, alluding to the victory of the Han Chinese to expel the Tubos with the legend of Buddhism subduing the heretics. This explanation may explain why the Buddhists in these paintings are painted as people from the Central Plains, while the outsiders are painted as Hu people.

Figure 12: "The Demon in Disguise" in Cave 196 of the Mogao Grottoes, late 9th century

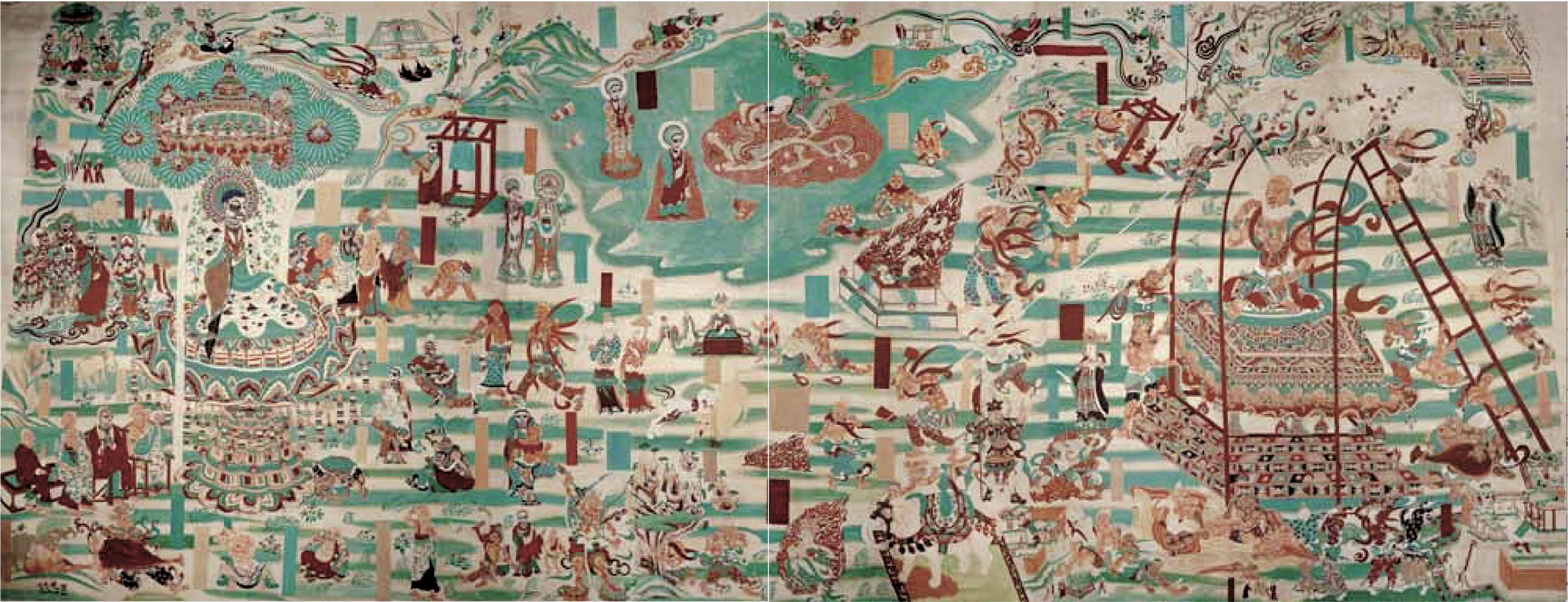

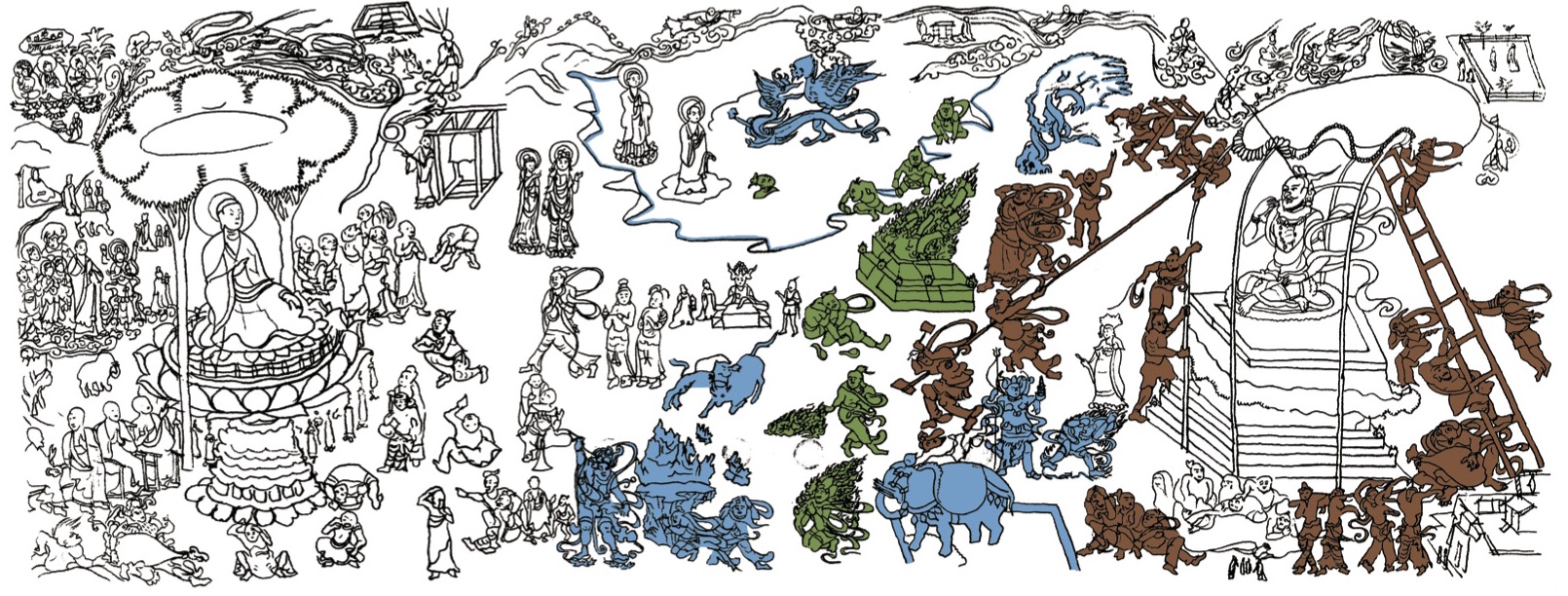

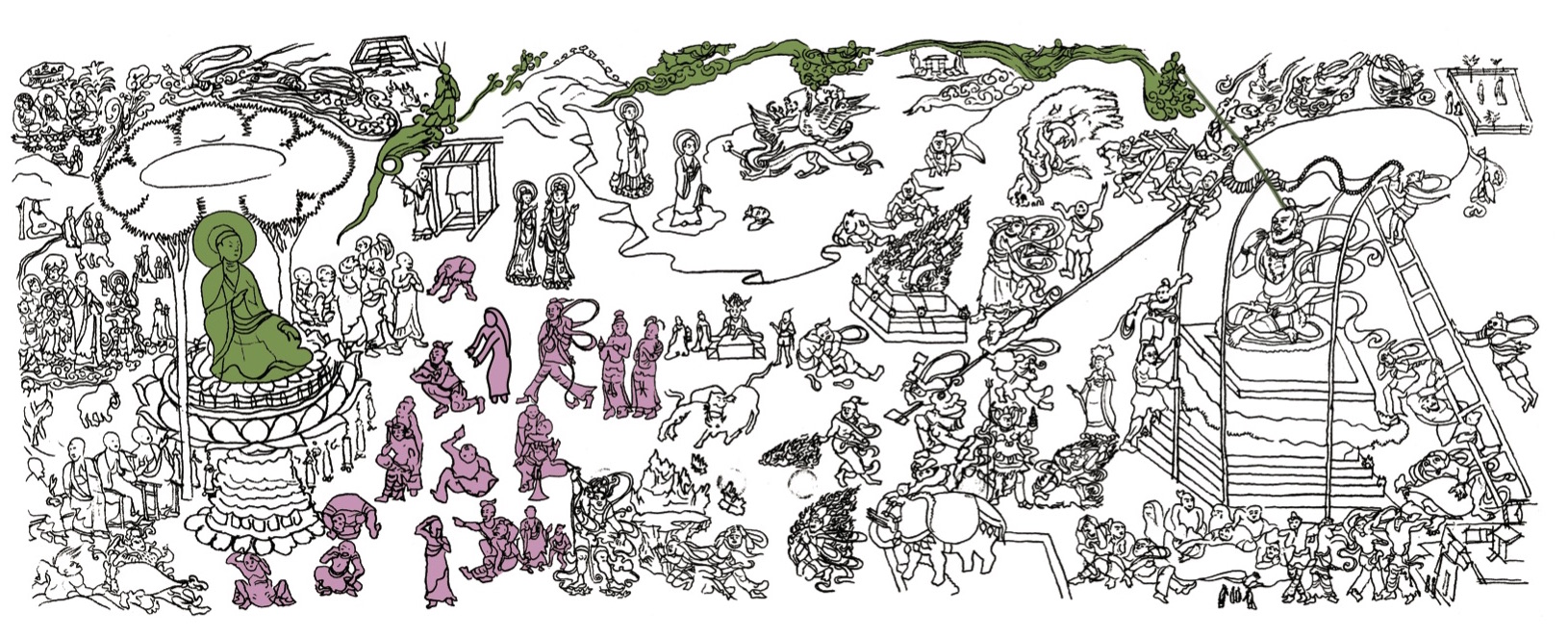

In this craze for excavating caves, the largest group of murals of "Subduing Demons" emerged, which are called "Subduing Demons" or "Subduing Demons in Disguise" because of their huge and independent composition. Although some of them were destroyed over the next millennium, at least 18 frescoes from the 9th and 10th centuries have survived in the Mogao Grottoes. Compared with earlier examples, these paintings are monumental works. The largest one is found in Cao Yijin Gongde Cave, numbered 98, with a width of 12.4 meters and a height of 3.45 meters. to 11 meters wide. These frescoes basically follow the same compositional pattern, and some examples—such as Cave 196 (Ho Master’s Cave) and the two in Cave 9—are so close that the same powder copy may be used. However, there are still a lot of differences in details, which reflects the autonomy and initiative of the painters in the creative process. The designs of these frescoes are extremely complex, and one often includes nearly fifty plots, each of which is explained by inscriptions written in rectangular boxes (Fig. 12). Since the texts in the inscriptions often transcribe or summarize "Conquering the Demons and Bianwen", some scholars believe that these murals must be used for Bianwen performances. However, this claim is difficult to hold for a number of reasons, including the special religious function of the grottoes, the inconsistency of the fresco structure with the narrative sequence of the scriptures, and the location and conditions of the paintings making them impossible to use for actual performances. In addition, the inscriptions of paintings are not always based on the script, and in many cases are created by the painter himself.

Figure 13: The interior of Cave 85 of Mogao Grottoes, you can see the "Devil in Disguise" late 9th century on the west wall behind the Buddha statue

Figure 14: Elevation and plan of Cave 196 of Mogao Grottoes, painted by Zhou Zhenru

However, all the 9th to 10th century murals of "Conquering the Demons" in the Mogao Grottoes were painted in this seemingly irregular fashion. How to make sense of these seemingly irregular pictures? One possible explanation is that the story of "Saying the Devil" was a household name during this period, and viewers would have no trouble recognizing it no matter how its plot was arranged. Another possibility is that these paintings hide deliberate "drawing puzzles" that require viewers to decipher to increase viewing interest. Some scholars believe that because this composition is difficult to interpret, it is necessary for the storyteller to guide the audience. However, all these explanations lack sufficient convincing force. For example, if the viewers at the time could easily identify the picture, then the numerous explanatory titles would seem meaningless. If these murals are deliberately set up a puzzle, then they should always provide some clues to solve the mystery, but what we see seems to be only the mystery without the answer. If these murals are the medium of rap performances, then they should at least be painted in places with enough space to watch, but these large-scale "Conquering the Devil" murals are often painted in dark places deep in the cave, and many even appear in hard-to-accommodate places. behind the back screen. In this dilemma, some scholars have to think that the design of these murals is an unexplainable "secret". In fact, in order to get out of this dilemma, we need to observe from a new angle. This observation includes two principles. First, in essence, religious art is mainly "image making" rather than "image viewing"; second, the process of image creation is different from writing and rap, and has its own logic. . The method of numbering the plots in the murals according to the narrative of Bianwen denies the logic of the images from the very beginning. This is because when the researchers marked these serial numbers on the pictures, they used a temporal reading logic, and they forgot that the most fundamental difference between painting and literature is its spatiality. In other words, the irregularity of these pictures is probably due to improper research methods. The picture itself is not necessarily without logic, but its logic is visual and spatial logic.

Figure 15: Schematic diagram of the narrative sequence of "Conquering Demons in Disguise" in Cave 9 of the Mogao Grottoes, illustrated by Li Yongning and Cai Weitang

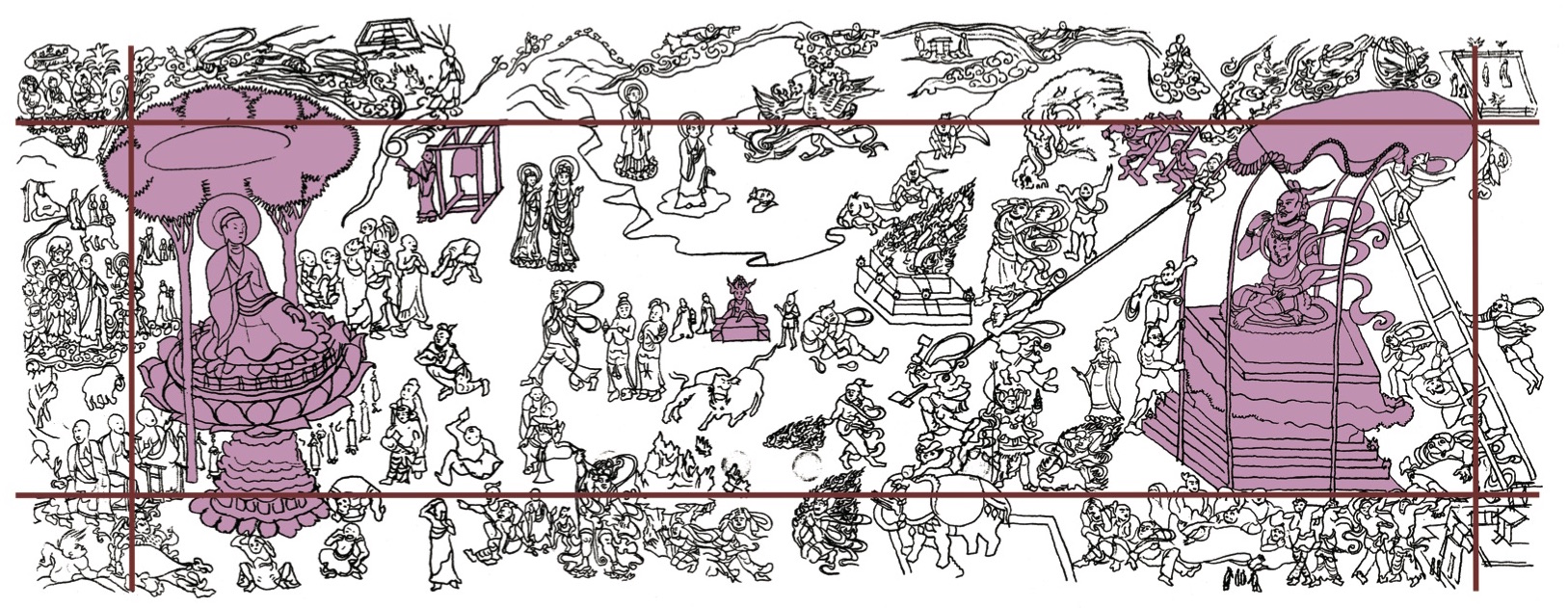

To explore this visual and spatial logic we need to change course and adopt a different analytical approach. The premise of this method is that each mural is designed from the whole, and therefore must be viewed as a whole. Our first task is to determine the basic compositional structure of the whole painting, rather than reading from individual episodes as in literature. That is to say, we should imagine that when ancient painters created these murals, the first thing to consider is the "operating position", that is, to carry out a general spatial conception of the picture, and then select and create details according to this conception, rather than passively Draw from the first plot to the last in the order of the text. This analytical approach allows us to shift our research focus from pursuing the literary provenance of a painting to exploring its compositional logic and creative process.

Figure 16: Basic compositional elements of the fresco "Conquering the Demons" in Cave 196 of the Mogao Grottoes, painted by Wu Hung

If we observe the frescoes in the later period of the Mogao Grottoes "Conquering the Demons" in this way, a clear visual logic will suddenly appear in front of our eyes. The logic can be summed up as follows: all these frescoes have a standard structure based on five picture elements: the king is in the center, the front is seated on the central axis of the picture (Fig. 16-1); the king is flanked by two opposite groups Figures and instruments: Lauducha and the golden drum are on the right (Figs. 16-2b, 3b), and Sariputra and the golden bell are on the left (Figs. 16-2a, 3a). This structure originates from the duality space established by the 7th century frescoes in Cave 335, and at the same time combines the images of bells, drums, kings and other images in the 8th century scroll of "Conquering the Demons".

Figure 17: The "Paired Image" of the mural of "Conquering the Demons" in Cave 196 of the Mogao Grottoes, painted by Wu Hong

Continuing the tradition of Cave 335, the painters of the later "Conquering the Devil" selected more images and plots from the script to form "pairs". These mirror images are added to the binary composition to reinforce the theme of the whole painting, namely the struggle between Buddhism and heresy. If the literature does not provide an exact pair, the painter will invent one. As a result, there are four eminent monks next to Shariputra (Fig. 17-4a), and next to Laoducha there are four "waitresses" (Fig. 17-4b). There are six foreign teachers in the Laoducha camp (Figure 17-5b), and six monks are added to the Buddhist side (Figure 17-5a). There is a wind god in the lower left corner of the picture on the Shariputra side (Fig. 17-6a), and a "foreign wind god" is added in the lower right corner of the picture on the Laoducha side for balance (Fig. 17-6b). The script mentioned two "great bodhisattvas" who helped Shariputra to subdue the demons (Fig. 17-7a), and the painter added two "outer goddesses" to help Laoducha (Fig. 17-7b). If you add the two main competitors, the golden bell and the golden drum, and the scene of the six fights, more than half of the images in the painting belong to this kind of binary image or "opposition" image.

Figure 18: The overall spatial structure of the frescoes in Cave 196 of the Mogao Grottoes, "Conquering the Demons", painted by Wu Hung

Although these images flesh out the binary space structure of the overall picture, the structure is still static. In order to inject temporal narrative into this spatial structure, the painter adopts another method. When the basic binary structure is established, they naturally divide the picture into five parts, four of which are distributed along the four sides of the picture, and the fifth part is centered (Fig. 18). Each part or space is then given a spatial meaning according to the prevailing concept of the universe at the time: the horizontal space at the bottom of the picture is regarded as the "earth" and the "world", so cities such as Shave and Rajasha are depicted here, as well as A scene from the monastery. The space along the upper edge of the picture is regarded as "heaven" and "Buddha country". Therefore, Shariputra is flying and changing here, and the upper left corner of the picture is painted with the brilliant image of Sakyamuni sitting on the Vulture Mountain. Some of the murals place Gion in the upper right corner of the picture—a place that also earned a place in the celestial realm as a holy site for Buddha’s sermons.The vertical spaces on both sides of the picture immediately connect the heaven and the human world. In the space on the left, Shariputra, sitting in meditation under the tree, wandered around the Vulture Mountain and sought the help of the Buddha before the fight. He then returned to the ground along the same vertical route, followed by a large group of Buddhist deities, including the eight god-kings, the giants holding the sun and the moon in their hands, and the elephant kings and golden-maned lions of the Himalayas. However, the painter seemed to have difficulty finding a suitable image to connect the upper right corner of Gion and the lower right corner of the castle, and as a result, the designer of the murals in the He Master Cave (cavity 196) found a passage from the old story of "The Book of Wise and Fool". , said that when Shariputra surrendered to the apostate, "the World Honored One and all the four groups surrounded the front and back, magnifying the light, shaking the heavens and the earth, and reaching the kingdom of Wei." The painter then painted this scene in the vertical space on the right.

Figure 19: Detail of the fighting method in the fresco "Conquering the Demons" in Cave 196 of the Mogao Grottoes, painted by Wu Hung

The center of the frame provides the largest picture space, and naturally becomes the battle field between Shariputra and Lauducha. More than 50 characters appear here, in different states such as fighting, struggling, crying, and escaping. While the first impression of this scene seems chaotic, a closer look reveals that all the characters belong to three distinct areas and related plots. The area along the central axis concentrates various fighting scenes. From the lower end, King Kong smashes the mountain, the white elephant drains the pool, the King Bishamon stands beside a burning ghost, and the lion swallows the water buffalo (marked in blue in Figure 19). At the top of the series is a dragon wrestling with a Garuda, which is clearly drawn above because both animals are associated with the celestial realm (Fig. 20). In this central area, the painter also added fighting scenes that were not mentioned in "Conquering the Demons" and other literary versions, including Shariputra handing the turban to the apostate who could not fold it; Immediately burnt; heretics tried to attack Sariputra by fire, but fell into a stupor or drifted into the sea from exhaustion; outsider immortals drove the square beam tablet with a spell but Shariputra condensed it in the air, etc. (marked in green in Figure 19) .

Figure 20: Garuda subdues the poisonous dragon, Cave 196

Figure 21: Laoducha and Outlander were attacked by strong winds, Cave 196

The second area in the center section is centered on the Laudo Fork on the right, where the outer lanes are all battling the hurricane. The canopy on Laudo's fork was blown to the brink, and his followers struggled to fix it (marked in ochre in Fig. 19). Some climbed ladders to repair it, while others drove piles into the ground with hammers, trying to hold on to the crooked roof. Others can only cover their faces with their hands under the attack of strong winds and give up resistance (Figure 21). In these later frescoes of "Conquering the Devil", this plot has been separated from the six fights and developed into a theme that dominates the pictorial narrative.

Figure 22: The scene of Shariputra vacating the sky, giving up Huishui and subduing the outsider and Laoducha's awakening and subjugation in Cave 196 of Mogao Grottoes, painted by Wu Hung

In order to balance the left and right sides in the middle of the picture, the painter added a group of scenes where the outsiders surrendered to Shariputra on the left (marked in pink in Figure 22). This episode is only briefly described in the Bianwen, but it is expanded into more than a dozen dramatic episodes in these frescoes, including Laoducha's reverence for the holy monk led by the Master Niganzi to the seat of Sariputra ( Figure 23); The outsider witch offered oil lamps to Shariputra, etc. Some newly converted heretics are still ignorant of Buddhist teachings, while others who have been admitted are shampooing, shaving their heads, brushing their teeth, and rinsing their mouths (Figure 24). The painter created these pictures and wrote inscriptions to explain them, enriching the original Bianwen story with new narrative links.

Figure 23: Conversion of Shariputra and Apostles, Cave 196

Figure 24: Refuge of the heretics, cave 196

It is worth emphasizing that the description we have made here also tells the story of "The Demon", but it does not follow the narrative sequence of the script. This is because the story has been given a new form in the fresco: the painter disintegrates the text into individual characters, events, and plots, and then reassembles these fragments in an augmented spatial form. When these characters and events are drawn in specific locations, their spatial relationship in turn prompts the painter to create new narrative connections. Although the images are largely faithful to the brevity, the spatial location of the images gives the painter an important gain.Based on the above discussion on the murals of "Conquering the Demons" in the late Tang Dynasty in Mogao Grottoes, we can see that their creators first constructed a spatial dualistic overall picture through "operating location". The first thing the audience sees in this picture is the theme of the picture, that is, "Subduing the Devil" or "Saint of God". This theme is interpreted, intensified and enriched by binary images that fill the picture. Even though many of these images are derived from texts, their spatial relationships in the frescoes recreate their connection to each other. Although these murals are not used for actual performances, they tell the story of "The Conqueror" in its own way - a story that is no longer a literary narrative created by writers or rappers, but a spatial narrative created by painters .

(This article is excerpted from Life·Reading·Xinzhi Sanlian Publishing, Wu Hung's book "Dunhuang in Space - Entering Mogao Grottoes", the original title is "Space in Mogao Grottoes Painting")