Emerson was once called "Confucius of America" and "Father of American Civilization" by former U.S. President Lincoln. "Declaration of Independence in American Intellectual and Cultural Fields". As one of the important figures in the history of American literature and thought, Emerson not only influenced Thoreau, Whitman, Dickinson and Frost, but also inspired Nietzsche, Baudelaire, Proust, Wool husband and Borges, whose vitality still lingers 140 years after his death.

Recently, a book by the American historian and biographer Robert D. Richardson, "A Biography of Emerson: A Passionate Thinker", was published in simplified Chinese by Zhejiang Literature and Art Publishing House. This book was first published in 1995 and won the New York Times Book of the Year and the Parkman Award of the American Historian Association.

Emerson came from a pastoral family. He entered Harvard University at the age of 14, served as the pastor of the Second Church in Boston at the age of 26, and began to emerge as a speaker and writer at the age of 30. His major works include "Nature" (1836), "Prose" (No. 1, 1841; No. 2, 1844), "Poems" (1847), "Representatives" (1850), "Characteristics of the Englishman" "(1857), "The Code of Life" (1860), "May Day and Others" (1867), "Society and Solitude" (1870) and "Literature and Social Purpose" (1875), etc., published public speeches including As many as 1500 articles. In addition, he also left an astonishing number of notes and letters, providing valuable first-hand information for future generations to understand and study his life and growth process, as well as American society and culture.

Emerson came from a pastoral family. He entered Harvard University at the age of 14, served as the pastor of the Second Church in Boston at the age of 26, and began to emerge as a speaker and writer at the age of 30. His major works include "Nature" (1836), "Prose" (No. 1, 1841; No. 2, 1844), "Poems" (1847), "Representatives" (1850), "Characteristics of the Englishman" "(1857), "The Code of Life" (1860), "May Day and Others" (1867), "Society and Solitude" (1870) and "Literature and Social Purpose" (1875), etc., published public speeches including As many as 1500 articles. In addition, he also left an astonishing number of notes and letters, providing valuable first-hand information for future generations to understand and study his life and growth process, as well as American society and culture.

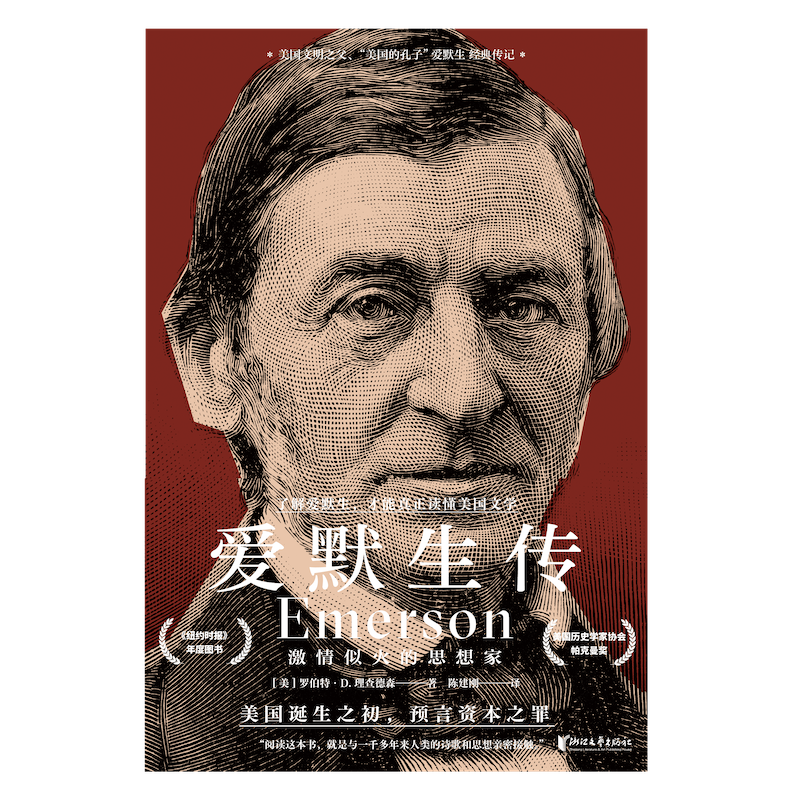

Emerson, 43 (original in Carlisle's London home, reproduced with permission from the Concord Public Library) All images courtesy of the publisher

In order to write Emerson's biography, Richardson lived in Emerson's hometown of Concord for a long time, studied a large number of Emerson's unpublished manuscripts, letters and private diaries, and read through Emerson's diary All works mentioned. Richardson attempts to present Emerson's daily life in its entirety, showing his reading, his habits and his personality, and to paint a true portrait of Emerson as a great writer and a common man, as well as his secret loneliness and love and hate.

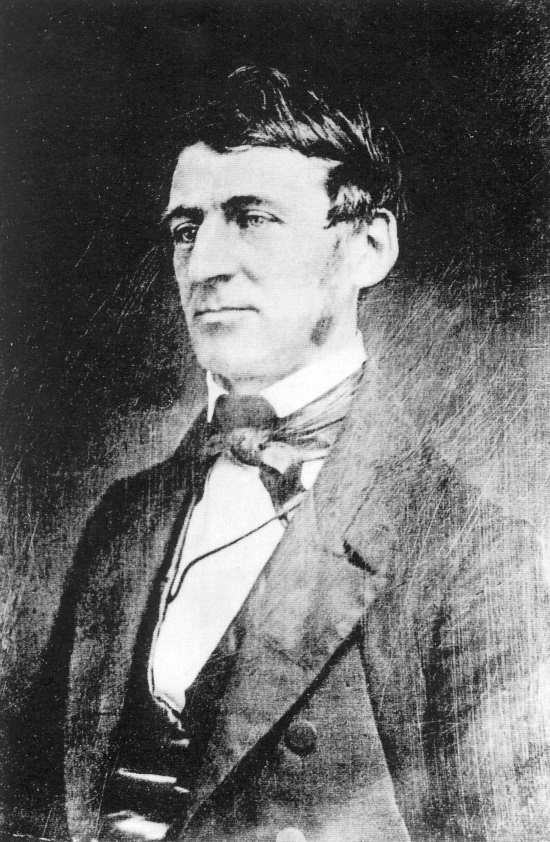

Ruth Haskins Emerson (1768-1853), Emerson's Mother (reprinted with permission from the Concord Public Library)

Richardson is also the author of the biographical work Thoreau: A Life of Mind at Walden Pond. In studying Thoreau and Emerson, Richardson read what they had read before trying to connect their reading with their writing. He originally planned to write Emerson's biography as a purely academic growth biography to match Thoreau's biography, but found that once he left Emerson's personal and social life, the growth of Emerson's academic wisdom would become difficult. understand. Thus, Emerson: The Passionate Thinker finally records Emerson's academic growth as well as his personal and social life.In Richardson's view, Emerson lived for ideas—he was a fanatical lover, obsessively pursuing ideas. At the same time, this great spokesman for individualism and self-reliance is also a loving neighbor, a devoted citizen, a loving and loving father, a faithful and reliable brother, and a lover A good friend of righteousness.

"Like Jefferson and Lincoln, Emerson's own life and his writings continue to influence and change Americans' self-perception. Because of this, biographies of him come out from time to time. Emerson never Written by certain groups, classes, or institutions, his work is often aimed at a single listener or reader. Compared to many other published and valuable biographies of Emerson, this biography (referring to The Biography of Emerson : The Passionate Thinker") is different in that it does not focus on Emerson's academic influence, but on Emerson himself, the individualist philosopher What kind of person is that," Richardson said.

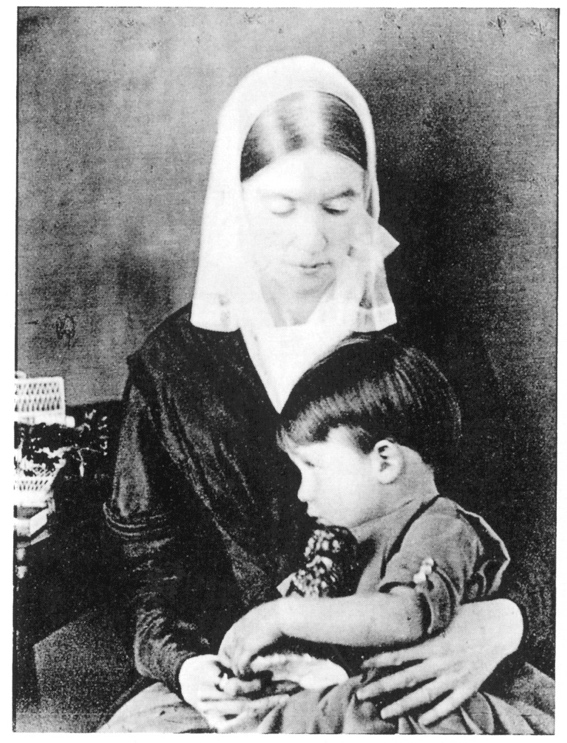

Lydian Jackson Emerson (1802-1892), Emerson's second wife and mother of children, pictured with second son Edward (1844-1930) in 1847 (with permission from the Concord Public Library post remake)

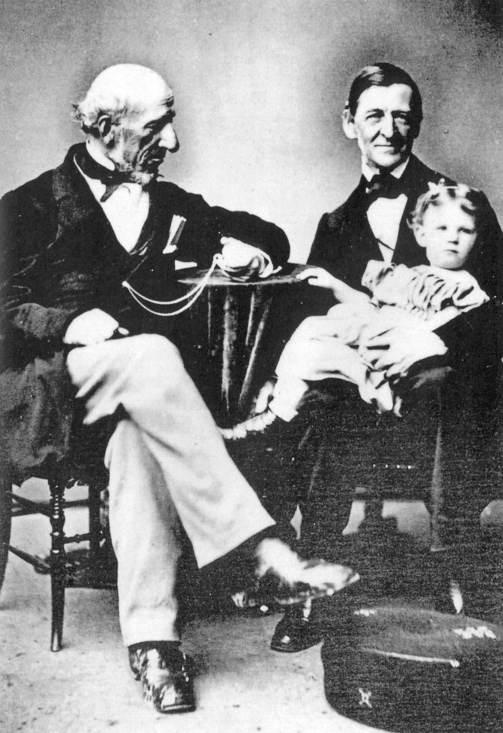

Emerson, 67, had his first grandson, Ralph Waldo Forbes (1866-1937). Another old man in the picture is John Forbes, his son William married Edith Emerson (the original picture is in the Massachusetts Historical Society, reprinted with the permission of the society)

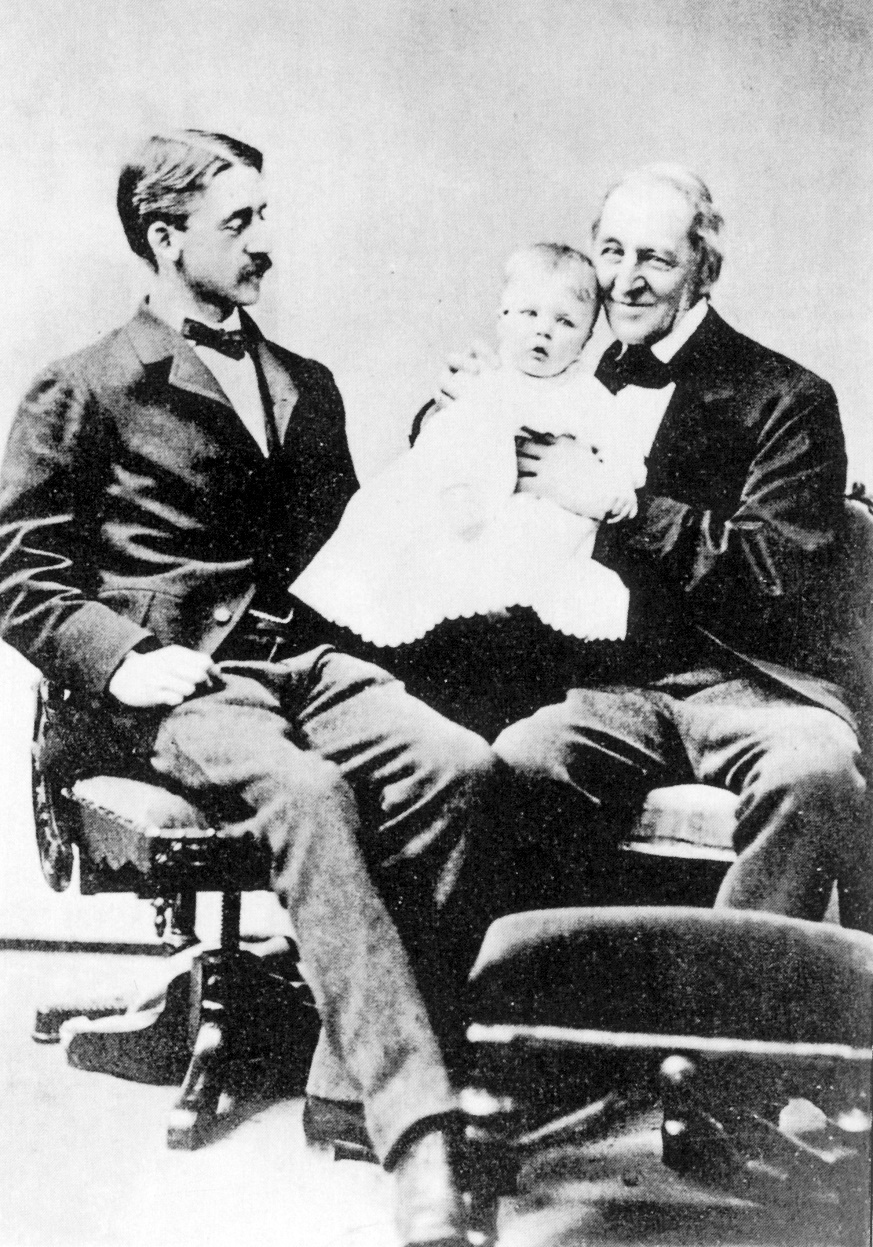

74-year-old Emerson with his second son Edward and Edward's son Charles Emerson (1876-1880) (reproduced with permission from the Concord Public Library)

The editor in charge of the Chinese edition of "The Biography of Emerson: The Passionate Thinker" told The Paper that although there are many biographies of Emerson, there are several special features in "The Biography of Emerson: The Passionate Thinker" : The first is the authoritativeness of the author and the classicity of the edition. Richardson has won the Bancroft Prize, the highest award in American history. It is this biography that focuses more on excavating Emerson himself, subverting people's traditional cognition of his "Concord saint", and striving to restore the "real life" under his reputation; finally, "Emerson Biography" also In particular, the precious images of Emerson and his family, the chronology of Emerson's life and other reference materials are included, hoping to provide readers with a window to understand Emerson in an all-round way.

Emerson in the 1850s (reproduced with permission from the Concord Public Library)

[Book Summary] The story of Emerson's emotional experience in "A Biography of Emerson: A Passionate Thinker"On March 29, 1832, 28-year-old Emerson came to the grave of his young wife Allen. Since his wife died a year and two months ago, it has become his habit to walk from Boston to his wife's grave in Roxbury every day. But today is different. What he does is no longer as simple as communicating with the soul of the deceased Alan, but to open his wife's coffin. Allen, young and beautiful, got engaged to him at the age of 17 and married him at the age of 18, but died of terminal tuberculosis when he was less than 20 years old. In order to cure her, the family tried every means, including taking a long journey to the country in a four-wheeled open-top carriage, in order to breathe a lot of fresh air. Because Ellen was always coughing up blood, their shared life was shrouded in a shadow almost from the beginning.

...

In his diary that day, Emerson wrote briefly: "I entered Ellen's grave and opened her coffin." They married on September 30, 1829, and their love was deep and complete. . The days of marriage seem to be very clear: travel together, write together, and write letters to express their thoughts; they laugh at the ascetic Shakers; she wants to be a poet, he wants to be a missionary. Emerson got the chance to preach in Boston, and they made their home there. The home then became the centerpiece of the Emerson family, as Waldo Emerson's mother and his younger brother Charles also moved in with them.

rise. But now, more than a year after the death of his wife Allen, Emerson's life is rapidly disintegrating, and his life is lonely and desolate. His mother had tried to persuade his ailing brother Edward to come back from the West Indies to take care of him. Emerson's career was also a mess, and while he was a beloved pastor at an important Boston church, he himself had trouble believing in immortality and he had doubts about the historical accuracy of the Bible. In fact, Emerson's career crisis is deepening sharply, and he can no longer play the role of pastor. He became suspicious of his beliefs and often felt empty and disoriented. his brother charles

Writing to Aunt Mary: "Waldo is ill...I've never seen him so depressed...he looks like he's going to break down."

In 1832, on the day Allen's tomb in Roxbury was opened, Emerson's life was on the verge of decadence. It has been more than ten years since she graduated from college, and her love is dead and her career is slim. He doesn't know what his true beliefs are, who he really is, or what he should do. He felt that "the fickle present is drifting away," replaced by a solid, unchanging past. "We walked on the lava that passed," he wrote.

(pages 003-005, death of first wife Alan)

Alan Tucker Emerson (1811-1831), Emerson's first wife (pocket photo, original in Concord Museum, reproduced with permission of the museum)

Charles Emerson and Elizabeth Hall were scheduled to marry in September 1836, three years after their engagement. After their marriage, the two plan to live in several additional rooms in Waldo and Lydian's new house. While Charles' health is slowly deteriorating, they plan for the future with hope. One day in April, Elizabeth was holding a measuring rope against the wall, trying to see if there was enough room for her piano, when she suddenly exclaimed: "It's futile, it's impossible." Charles had a cold, and his body was getting weaker and weaker, and to free himself from the "hot sea of fire in his chest", he went to New York to live with William. On May 9, Charles passed out while walking and died before being rushed by the hastily summoned Emerson and Elizabeth. Aunt Mary's darling, Milton's avid reader, the man his fiancée would later call "the smartest intellectual the state of Massachusetts has ever seen," the funny little brother, who danced around the table in a velvet cape, more than anyone else. The man who could make Emerson laugh out loud is gone.Emerson was hit hard. After the funeral, when leaving Charles' tomb, Emerson suddenly laughed strangely and said to the people next to him: "A man, who has never had many relatives to accompany him, and now even this only company has been taken away. Now, what is there worth living?" He wrote to Lydian from New York, saying he had lost a part of his body: "Through his eyes I saw so much." He said: "I not only Feeling lonely and out of place, and a little ashamed that I'm still alive." Two weeks later, still groping in the dark, he said: "The night covers everything around us, even though we can't get away from it. , but our nature is always after the day."

Emerson and Elizabeth had long conversations as they tried to separate the best of Charles—what he stood for, the meaning of his life—from his flesh. In the case of Emerson himself, the memory of Charles became his personal friendship principle or friendship archetype, and he found, not without grief, that whenever a friend "shows you a new quality...he tends to will be out of your sight." Both Charles' brother and Charles' fiancée tried to assuage their grief by constructing the image of Charles by replacing the personal immortality that Emerson no longer believed in with a worldly immortality. Emerson also tried to piece together what Charles had written into a book, but found that there were not many well-crafted articles, and most of them had too many traces of darkness, despair, and self-pity, and had to abandon the plan. . In some ways, Nature is Emerson's open letter to the world on behalf of Charles, who is also the "friend" at the end of the book's "knowledge" chapter.

After ten days of "helpless mourning," Emerson began to rediscover himself, even recalling the excitement and epiphany that trip to Auburn Hills gave him. He made a list of "partners who met my highest needs but were scattered around", among them Edward Stabler, Peter Hunt, Sampson Reed, Tabox, Mary Rowe Qi, Jonathan Phillips, Alcott and Murat, among others. He didn't put Mary Moody Emerson on the list, which may indicate that either she was with Emerson at the time of the list, or she was not in the same category as others, and her influence on Emerson was long-term. And stable, not the kind of casual friendship. There is also no Charles' name on the list.

(page 237, brother Charles dies)

January 1842 was a sad month. On New Year's Day, Henry Thoreau's brother John accidentally cut himself while sharpening his razor; on the 9th, he contracted tetanus, which doctors in Boston said was incurable. Henry, who had been living with the Emersons at the time, hurried back to his father's house to take care of John, but his brother died two days later. On January 20, Emerson concluded the Boston lecture series with images of a lonely wandering planet and stoic meditation. Two days later, on January 22, to the shock and inexplicable horror of friends and family, Henry Thoreau also developed symptoms of tetanus. However, the symptoms subsided in the early morning of the 24th. It turned out that he was not infected, but had a resonance reaction.

That night, at Emerson's house, little Waldo contracted scarlet fever. He started to have a fever and his temperature rose very rapidly. On January 27th, Waldo became a little delirious. Lydian had just left her son for a short rest when she heard him calling for mother; she returned and asked Dr. Bartlett if the child was getting better soon. "I had hoped he would have survived." That was the doctor's answer. It wasn't until that moment that Lydian realized that the child might not live much longer. A few hours later, at 8:15 p.m., the child left.

Little Allen got the same disease. That night, in order to take care of Ellen easily, Lydian asked her to sleep in the big bed with her, sleeping in her father's place. When Lydian talked to Emerson and Emerson's mother that dreadful night, she felt she could endure it all. But when she was alone, she collapsed completely. "Sad, miserable grief flooded my heart," she later wrote, "and I fear that the charm of earthly life will be destroyed forever." The next morning, nine-year-old Louisa May Alcott came to Emerson's house to ask if Waldo was better. Years later, she still remembered: "The way his father came to me, his face was haggard from the day-to-day care of Valdo, and his grief completely changed his appearance. I was startled and stammered. Out of my question. 'The boy, he's dead.' That's the answer. It was the first time in my life that I saw a person in grief," recalls Alcott.

The night Waldo died, Emerson wrote four text messages to friends and family, followed by six or seven the next day. In the letter, he repeated helplessly. "Farewell, goodbye." "My dear, my dear." "My child, my child is gone," he said to Margaret Fuller. "Do I dare to love anything more?" A month later, Emerson wrote to Carlisle, "You will never understand how much this child will take my life." Lydian has said before that she has a hard time understanding how people can actually feel The pain of others, and she herself now faces endless helplessness, heartbreak and grief. She understands that her husband's lack of pain is basically "theoretical", she said: "Every memorabilia related to his son evokes his endless longing for his son, and I can't describe it to you. . This is not a great hope lost, but a deepest love deprived.

The Emersons' grief is deep, real and immediate. This grief is expressed through letters, conversations, and poetry. Poetry is the most important way for Emerson. After a while, he wrote a long poem called "Lamentations", which is one of the greatest dirges in the English language. It is also Emerson's A poem that rivals Milton's; the dirge of Milton's "Lycidas" is well known to him. Emerson was deeply angry, shocked and distressed. He does not believe in traditional claims of an afterlife. He lost his son and the relief he had given him. But he was able to mourn through poetry, and perhaps that was the main reason why his greatest grief disappeared faster than Lydian. Emerson was far from being one of those stiff Yankees (as the joke goes, "Sam died Friday. He didn't want to talk about it"). When he told Caroline Sturgess in his letter that "I am sad because I cannot be sad," this Thoreau paradox may simply mean that he is a little chagrined that he is not, as Henry did, because of John Thoreau's death was completely overwhelmed by grief.

Waldo's death left a deep wound to the Emerson family that never fully healed. Allen, who was nearly 3 at the time, pointed out bitterly years later that Margaret Fuller could not accept the fact that Waldo was gone and that she — Ellen — survived. Over the next few years, Lydian's health deteriorated for a number of reasons, but the one that hit her the most directly and hit her the most was Valdo's death. Of Lydian's letters between 1843 and 1847, only one survives, a sad and bewildered letter to Emerson that reads, in part: "I have lost all the youth of Allen. . The other children are young and not yet grown, maybe I can take care of them. Valdo is safe now."

Six months after Waldo's death, Emerson wrote to a Baltimore wisher named Solomon Corner: "The strength of the soul is proportionate to the strength of its needs." If the first half of the sentence was For sure, then its last word is a world of pain. Emerson's ability to express also gave him the ability to mourn. "The south wind can bring/life, sunshine and hope," he wrote at the beginning of "Lamentations":

But in the face of the dead, it loses its magic,

cannot be resurrected;

Looking at the mountains from afar, mourning deeply,

My baby who never comes back.

(pages 384-386, death of eldest son Valdo)