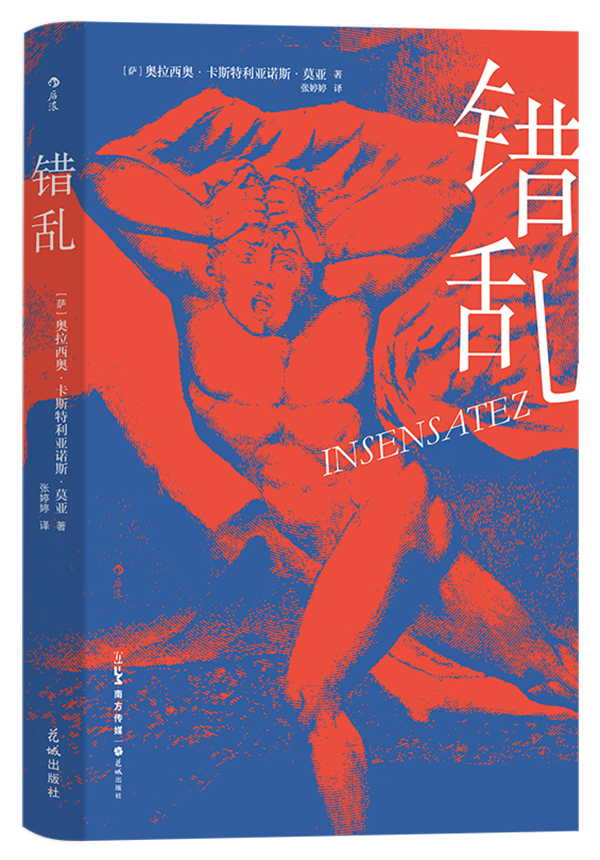

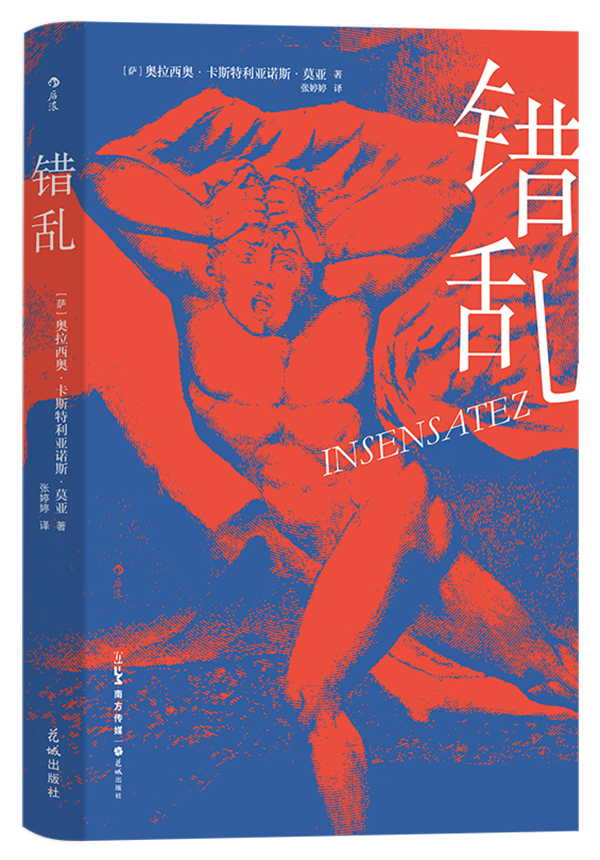

The Salvadoran writer Horacio Castellanos Moya is an important writer in the post-"literary explosion" era in Latin America. El Salvador, The Tyrant of Memory, The Dream of Homecoming, The Devil in the Mirror, Dancing with Snakes, etc., have won one of the highest awards in Spanish literature, the Manuel Rojas Medal. Recently, Moya's representative novel "Insanity" was launched by Houlang Literature. This is the first time that his works have been translated into Chinese and published.

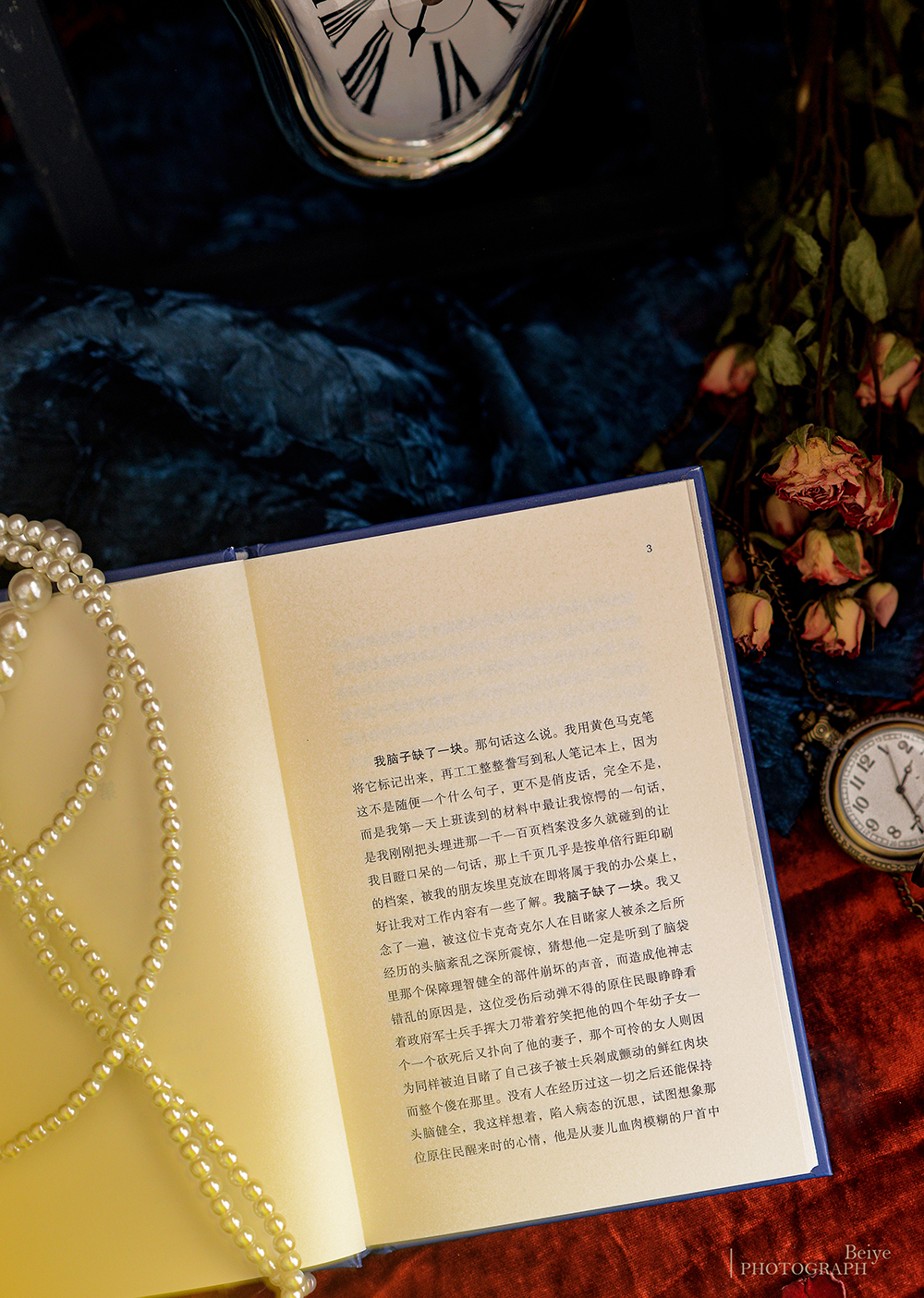

"Derangement" tells the story of a fugitive writer who is hired by a church in a Latin American country to edit an oral archive. The archive is 1,110 pages long and records the bloody testimonies of the local aborigines over the massacre by the army ten years ago. During the editing process, the writer grew delirious, while the executioner who still ruled the unnamed Latin American country loomed.

Although the novel does not name the United States, readers can speculate that the background of the novel is the atrocities committed by the military against its citizens during the 36-year Guatemalan Civil War. The oral file also alludes to the "historical memory" initiated by the Guatemalan Catholic Church. recovery plan".

After "Derangement" was launched in China, Moya accepted an exclusive interview with The Paper, which was the first Chinese media interview he accepted about "Derangement". He admits that he doesn't know much about China, nor does he know much about contemporary Chinese literature, but he will read Li Bai and Du Fu from time to time, "their poems are very beautiful, or they are the profound philosophical thoughts written by Zhuangzi."

In the novel, "fear" always accompanies the protagonist

The Paper: How long did the novel "Insanity" take to complete? What was the original source of inspiration?

Moya: That adds up to about five months. But it was completed in two stages: I started writing in early 2003, stopped writing in the middle, and finished it in mid-2004. The story revolves around a report on human rights in Guatemala released in 1997, but it does not directly describe the report, but rather the psychological impact of the report on the editor.

The Paper: The editor-the protagonist of the novel "I" is a writer who is exiled due to political reasons: he speaks wild words, has persecution delusions, accepts a job he doesn't really want to do for five thousand dollars, and uses a relationship between men and women. To vent the pressure... What is your attitude towards this protagonist? I feel a little joking and sarcastic?

Moya: The protagonist is a complex and somewhat contradictory character. I don't have a playful attitude towards him. If I can't get into the heart of the characters, I can't write this novel, and the banter and ridicule will create a distance and prevent me from writing. The character may be a little amusing, but those amusing elements stem from his character, from his worldview and the series of encounters his neurological disorder has inflicted on him.

The Paper: You have spent a lot of time on the protagonist's psychological activities. For example, in the face of the heavy massacre oral archives, "I" sees their literary nature rather than political and historical nature. This way of writing is hidden behind What are your thoughts?

Moya: Fiction is psychological in nature, a construction of a certain mental state, a certain way of thinking and a sense of belonging. As far as the protagonist in "Derangement" is concerned, there is a persistent contradiction between himself and the society in which he lives, and he lives in this contradiction. He doesn't believe in what he's doing, but he has to; he doesn't believe in the values of his team, but he still has to pretend to. He was a man of no faith, caught in an environment permeated with faith, not just religious faith, but faith in those supposedly vital values to humanity.

The Paper: In this story, "fear" has always accompanied the protagonist, including fear of political persecution, fear of massacre memories, fear of love murder, fear of sexually transmitted diseases... They are so ubiquitous. However, it seems that it is precisely because of "fear" that "I" was spared the fate of being assassinated like the archbishop. As a writer, how do you understand "fear"? What "fears" do you think humans cannot overcome or even face?

Moya: Fear is part of human nature. Nietzsche said in Thus Spoke Zarathustra that fear is a basic human emotion that is passed down from generation to generation. Fear is the fear of being pushed to the extreme, pushed to the apex of an explosion. Fear will always be with us, sometimes veiled and other times revealed.

Moya: There is no doubt that violence is part of human nature, part of its natural attributes in a broad sense. With the help of education and legislation, the long process of civilization has tried to tame human violent tendencies, but human violence can be controlled and quelled, but it cannot disappear unless the human species disappears. Violence and fear are two sides of the same coin.

The Paper : For writers, the process of writing novels may also be a process of thinking. What are the main questions you think about in "Derangement"?

Moya : During the writing process, I thought about very specific issues, that is, how to keep the plot, characters, environment, scenes and other elements coherent. I don't think about those broad abstract questions. Only think about it after writing it. My writing process is intuitive, not conceptual.

As a writer, options are limited

The Paper : You resist the labels of "political novel writer" and "violent novel writer", but you also admitted that your writing is full of violent elements. As a writer, what do you think is optional? What is not optional?

Moya : Our options are very limited. We are a product of our social environment, our family background, and our relationships, and we cannot fully transcend these limitations. Creative themes are imposed on me as part of my life, they are part of my personal experience, part of the time and place I am in. The only choice I have is the way of expression, the angle of observation, and ultimately how to bring it to the pen. But even in these active choices, I was always constrained by my own nature and my own sensory conditions. For example, I'm still not sure if I'm more visual or auditory, and that's reflected in my storytelling style, which affects whether I'm better at delineating environments or creating sounds. Our options are extremely small. I like the ancient Greek view of destiny.

The Paper: As a Latin American writer, where do you think your literary resources come from? You once said, "Our generation of Latin American writers is closer to American writers in terms of how we understand the world and what we're talking about than magical realism." Why your generation of Latin American writers has a worldview "closer to American writers" "? Does this have anything to do with your reading source?

Moya: I say this sentence in a specific context. I was reading passionately about the great American writers of the first half of the twentieth century: Faulkner, Hemingway, Raymond Chandler, Truman Capote, Flannery O'Connor, Dahir Hammett, Carson McCullers, etc. I have no interest in contemporary American literature. There is an ideological climate dominated by Puritan sentimentalism in contemporary American literature, and I have little interest.

The Paper : Do you have any favorite works in Latin American literature?

Moya : The word "favorite" is very popular among our contemporary people. I would use it to describe objects, but not literature. There are writers and works that I keep rereading (Onetti, Rolfo, Borges, Cesar Vallejo, Cabrera Infante, Roger Dalton, etc.) is the first that springs to mind). Why do you like them? Because they inspire me about life, about what it means to live in this world, about how to do literature, and how to look at the profession of being a writer.

The Paper : Besides writing and reading, what other things or topics are you usually interested in?

Moya : I occasionally watch movies. When reading newspapers, pay more attention to international politics and crime news. Going out for a beer in the afternoon. The rest of the time, silent.

The Paper : "Insanity" is the first time your work has been translated into Chinese and published in China. What did you know about China before? What are you confused about? As far as this work is concerned, what do you expect from Chinese readers?

Moya : My little knowledge of China is limited to some reports published in newspapers and magazines in Western countries. Only by visiting a country in person can it be possible to talk about understanding. For example, I lived in Germany for two years, Mexico for thirteen years, Spain for two years, Guatemala for two years, Japan for six months, and the United States for twelve years. Sweden with her daughter. I can barely comment on these countries, but I have never visited such a vast and historic China, so I dare not express any opinion. When French writer Andre Malraux interviewed Mao Zedong and asked him what he thought of the French Revolution of 1789, Mao replied that it was too early to express an opinion on that event. I find it interesting to understand time and history in this way.

The Paper: Have you read the works of Chinese writers? If so, I would also love to hear your comments on Chinese literature.

Moya: I'm sorry to disappoint you. It's prudent to express opinions on things you don't understand. I haven't read any of the Chinese writers who are famous in the contemporary media, like Mo Yan and Mai Jia. Will read it one day. I read Li Bai and Du Fu from time to time, their poems are wonderful, or the profound philosophies of Zhuangzi, but I know very little about contemporary Chinese literature.

Novels create their own reality

The Paper: In your opinion, the pillar of "witness literature" (represented by the autobiography of Maya- Kiche human rights fighter Rigoveta Menchu) is historical truth, but reality is complex, and there is no single true story. . Has your experience of more than 20 years of journalism—what we call "non-fiction"—in Mexico and Guatemala influenced your attitude toward "witness literature"?

Moya: I think it was that experience that made me understand why I didn't like "witness literature" as a literary genre. A group of people who promote a political point of view by telling their own experiences of victimization call this type of writing "witness literature." I have no sympathy for political propagandists. What I am interested in is memory, the autobiographical writing that carries memory, and the image of the writer highlighted by these words must reveal all the contradictions, misfortune, morality, and cowardice in his heart.

The Paper : In the past ten years, the Chinese literary community has paid more and more attention to "non-fiction". There are also views that fiction represented by novels can no longer respond to today's reality, and cannot establish a real and effective relationship with the present, so it can only turn to non-fiction. Fiction seeks a kind of help. In your opinion, what textual expressions might establish a real and effective relationship with the present?

Moya: The situation stemmed from a misunderstanding caused by a lack of thought. Fiction never has the function of "establishing a real and effective relationship with the present". Some can, others can't. Stendhal, Kafka, Melville—to name just three—were all considered great writers many years after they died, many years after they were writing. Based on your description, I speculate that there are many people in China who suffer from that kind of disease infected by technology: I think that only what is present, instantaneous, and can get immediate satisfaction from it is worth writing about. Understanding the world in this way cannot create lasting literature. I don't see literary creation as one of the many disposables in the contemporary era. Recently, after a few decades, I reread The Brothers Karamazov and found that it conveys far more insights about human beings than most of the "now" works I've read.

Moya: I don't talk about what I'm writing, it brings bad luck and blocks the mind. As for the new crown epidemic, it is nothing more than reaffirming the vulnerability of the human species. During the pandemic, before getting vaccinated, I flew across the Atlantic four times and spent the night on an airport couch. For me, the Covid-19 pandemic is a deafening noise; and a nightmare, because travel has become so difficult and the masks are taking my breath away. die? In my country, crime has long been a culture, and everyone has to learn to live with death. I was afraid of death, like everyone else, but I knew it was inevitable. Death can come suddenly at any moment, and there is nothing I can do to stop it.

The Paper: Since 2020, the novel coronavirus has become the object or point of writing for a group of writers. What do you think of it?

Moya: If writers don't have themes that stir up their internal organs and require them to write, then they will naturally go to contemporary reality to find themes, which is understandable. But I never wanted to write a novel about the epidemic myself, and I didn’t need to. After my experience settles down, I may write in the future. "Reality" is an intractable concept, which is why novels try to create their own reality, and the truth in novels is based on credibility, not the era they reflect.

Note: Zhang Tingting, the Chinese translator of "Crazy", provided translation assistance for this interview, and I would like to express my thanks.

"Derangement" tells the story of a fugitive writer who is hired by a church in a Latin American country to edit an oral archive. The archive is 1,110 pages long and records the bloody testimonies of the local aborigines over the massacre by the army ten years ago. During the editing process, the writer grew delirious, while the executioner who still ruled the unnamed Latin American country loomed.

Although the novel does not name the United States, readers can speculate that the background of the novel is the atrocities committed by the military against its citizens during the 36-year Guatemalan Civil War. The oral file also alludes to the "historical memory" initiated by the Guatemalan Catholic Church. recovery plan".

Recently, Moya's representative novel "Insanity" was launched by Houlang Literature. This is the first time that his works have been translated into Chinese and published.

Central America remains one of the highest concentrations of violence in the world. At a Literary Forum of the House of America in Madrid, Moya said, "We are also the product of a massacre. That's why we are so fond of jokes. We use laughter to ward off insanity." "Insanity" is also an absurd In the dark comedy, Roberto Bolaño once said: "The sharp humor in his (Moya) works is like a Buster Keaton movie, and like a time bomb, enough to To deter the fragile sense of stability of those idiots (nationalists), let them get out of control, and wish to hang the author in the public square.”After "Derangement" was launched in China, Moya accepted an exclusive interview with The Paper, which was the first Chinese media interview he accepted about "Derangement". He admits that he doesn't know much about China, nor does he know much about contemporary Chinese literature, but he will read Li Bai and Du Fu from time to time, "their poems are very beautiful, or they are the profound philosophical thoughts written by Zhuangzi."

Horacio Castellanos Moya (1957- )

【dialogue】In the novel, "fear" always accompanies the protagonist

The Paper: How long did the novel "Insanity" take to complete? What was the original source of inspiration?

Moya: That adds up to about five months. But it was completed in two stages: I started writing in early 2003, stopped writing in the middle, and finished it in mid-2004. The story revolves around a report on human rights in Guatemala released in 1997, but it does not directly describe the report, but rather the psychological impact of the report on the editor.

The Paper: The editor-the protagonist of the novel "I" is a writer who is exiled due to political reasons: he speaks wild words, has persecution delusions, accepts a job he doesn't really want to do for five thousand dollars, and uses a relationship between men and women. To vent the pressure... What is your attitude towards this protagonist? I feel a little joking and sarcastic?

Moya: The protagonist is a complex and somewhat contradictory character. I don't have a playful attitude towards him. If I can't get into the heart of the characters, I can't write this novel, and the banter and ridicule will create a distance and prevent me from writing. The character may be a little amusing, but those amusing elements stem from his character, from his worldview and the series of encounters his neurological disorder has inflicted on him.

The Paper: You have spent a lot of time on the protagonist's psychological activities. For example, in the face of the heavy massacre oral archives, "I" sees their literary nature rather than political and historical nature. This way of writing is hidden behind What are your thoughts?

Moya: Fiction is psychological in nature, a construction of a certain mental state, a certain way of thinking and a sense of belonging. As far as the protagonist in "Derangement" is concerned, there is a persistent contradiction between himself and the society in which he lives, and he lives in this contradiction. He doesn't believe in what he's doing, but he has to; he doesn't believe in the values of his team, but he still has to pretend to. He was a man of no faith, caught in an environment permeated with faith, not just religious faith, but faith in those supposedly vital values to humanity.

The Paper: In this story, "fear" has always accompanied the protagonist, including fear of political persecution, fear of massacre memories, fear of love murder, fear of sexually transmitted diseases... They are so ubiquitous. However, it seems that it is precisely because of "fear" that "I" was spared the fate of being assassinated like the archbishop. As a writer, how do you understand "fear"? What "fears" do you think humans cannot overcome or even face?

Moya: Fear is part of human nature. Nietzsche said in Thus Spoke Zarathustra that fear is a basic human emotion that is passed down from generation to generation. Fear is the fear of being pushed to the extreme, pushed to the apex of an explosion. Fear will always be with us, sometimes veiled and other times revealed.

opening

The Paper: There is one detail in the novel that left a deep impression on me. It is that the protagonist is in a spiritual asylum. Facing the testimony of victims of the Holocaust, he loses his attention from time to time, and only fantasizes that he is the torturer of the Holocaust. to be temporarily relieved. This detail is intriguing because it simultaneously points to three disorganized subjects: the victims of the Holocaust, the torturers of the Holocaust, and the witnesses of the Holocaust years later. What observations do you have about human nature in this description? Do you think violence is a part of human nature?Moya: There is no doubt that violence is part of human nature, part of its natural attributes in a broad sense. With the help of education and legislation, the long process of civilization has tried to tame human violent tendencies, but human violence can be controlled and quelled, but it cannot disappear unless the human species disappears. Violence and fear are two sides of the same coin.

The Paper : For writers, the process of writing novels may also be a process of thinking. What are the main questions you think about in "Derangement"?

Moya : During the writing process, I thought about very specific issues, that is, how to keep the plot, characters, environment, scenes and other elements coherent. I don't think about those broad abstract questions. Only think about it after writing it. My writing process is intuitive, not conceptual.

As a writer, options are limited

The Paper : You resist the labels of "political novel writer" and "violent novel writer", but you also admitted that your writing is full of violent elements. As a writer, what do you think is optional? What is not optional?

Moya : Our options are very limited. We are a product of our social environment, our family background, and our relationships, and we cannot fully transcend these limitations. Creative themes are imposed on me as part of my life, they are part of my personal experience, part of the time and place I am in. The only choice I have is the way of expression, the angle of observation, and ultimately how to bring it to the pen. But even in these active choices, I was always constrained by my own nature and my own sensory conditions. For example, I'm still not sure if I'm more visual or auditory, and that's reflected in my storytelling style, which affects whether I'm better at delineating environments or creating sounds. Our options are extremely small. I like the ancient Greek view of destiny.

The Paper: As a Latin American writer, where do you think your literary resources come from? You once said, "Our generation of Latin American writers is closer to American writers in terms of how we understand the world and what we're talking about than magical realism." Why your generation of Latin American writers has a worldview "closer to American writers" "? Does this have anything to do with your reading source?

Moya: I say this sentence in a specific context. I was reading passionately about the great American writers of the first half of the twentieth century: Faulkner, Hemingway, Raymond Chandler, Truman Capote, Flannery O'Connor, Dahir Hammett, Carson McCullers, etc. I have no interest in contemporary American literature. There is an ideological climate dominated by Puritan sentimentalism in contemporary American literature, and I have little interest.

The Paper : Do you have any favorite works in Latin American literature?

Moya : The word "favorite" is very popular among our contemporary people. I would use it to describe objects, but not literature. There are writers and works that I keep rereading (Onetti, Rolfo, Borges, Cesar Vallejo, Cabrera Infante, Roger Dalton, etc.) is the first that springs to mind). Why do you like them? Because they inspire me about life, about what it means to live in this world, about how to do literature, and how to look at the profession of being a writer.

The Paper : Besides writing and reading, what other things or topics are you usually interested in?

Moya : I occasionally watch movies. When reading newspapers, pay more attention to international politics and crime news. Going out for a beer in the afternoon. The rest of the time, silent.

The Paper : "Insanity" is the first time your work has been translated into Chinese and published in China. What did you know about China before? What are you confused about? As far as this work is concerned, what do you expect from Chinese readers?

Moya : My little knowledge of China is limited to some reports published in newspapers and magazines in Western countries. Only by visiting a country in person can it be possible to talk about understanding. For example, I lived in Germany for two years, Mexico for thirteen years, Spain for two years, Guatemala for two years, Japan for six months, and the United States for twelve years. Sweden with her daughter. I can barely comment on these countries, but I have never visited such a vast and historic China, so I dare not express any opinion. When French writer Andre Malraux interviewed Mao Zedong and asked him what he thought of the French Revolution of 1789, Mao replied that it was too early to express an opinion on that event. I find it interesting to understand time and history in this way.

The Paper: Have you read the works of Chinese writers? If so, I would also love to hear your comments on Chinese literature.

Moya: I'm sorry to disappoint you. It's prudent to express opinions on things you don't understand. I haven't read any of the Chinese writers who are famous in the contemporary media, like Mo Yan and Mai Jia. Will read it one day. I read Li Bai and Du Fu from time to time, their poems are wonderful, or the profound philosophies of Zhuangzi, but I know very little about contemporary Chinese literature.

Novels create their own reality

The Paper: In your opinion, the pillar of "witness literature" (represented by the autobiography of Maya- Kiche human rights fighter Rigoveta Menchu) is historical truth, but reality is complex, and there is no single true story. . Has your experience of more than 20 years of journalism—what we call "non-fiction"—in Mexico and Guatemala influenced your attitude toward "witness literature"?

Moya: I think it was that experience that made me understand why I didn't like "witness literature" as a literary genre. A group of people who promote a political point of view by telling their own experiences of victimization call this type of writing "witness literature." I have no sympathy for political propagandists. What I am interested in is memory, the autobiographical writing that carries memory, and the image of the writer highlighted by these words must reveal all the contradictions, misfortune, morality, and cowardice in his heart.

The Paper : In the past ten years, the Chinese literary community has paid more and more attention to "non-fiction". There are also views that fiction represented by novels can no longer respond to today's reality, and cannot establish a real and effective relationship with the present, so it can only turn to non-fiction. Fiction seeks a kind of help. In your opinion, what textual expressions might establish a real and effective relationship with the present?

Moya: The situation stemmed from a misunderstanding caused by a lack of thought. Fiction never has the function of "establishing a real and effective relationship with the present". Some can, others can't. Stendhal, Kafka, Melville—to name just three—were all considered great writers many years after they died, many years after they were writing. Based on your description, I speculate that there are many people in China who suffer from that kind of disease infected by technology: I think that only what is present, instantaneous, and can get immediate satisfaction from it is worth writing about. Understanding the world in this way cannot create lasting literature. I don't see literary creation as one of the many disposables in the contemporary era. Recently, after a few decades, I reread The Brothers Karamazov and found that it conveys far more insights about human beings than most of the "now" works I've read.

"Confused"

The Paper: Are you writing a new novel? The global outbreak of the new crown epidemic in 2020, how has your life changed? Did you come up with some new ideas?Moya: I don't talk about what I'm writing, it brings bad luck and blocks the mind. As for the new crown epidemic, it is nothing more than reaffirming the vulnerability of the human species. During the pandemic, before getting vaccinated, I flew across the Atlantic four times and spent the night on an airport couch. For me, the Covid-19 pandemic is a deafening noise; and a nightmare, because travel has become so difficult and the masks are taking my breath away. die? In my country, crime has long been a culture, and everyone has to learn to live with death. I was afraid of death, like everyone else, but I knew it was inevitable. Death can come suddenly at any moment, and there is nothing I can do to stop it.

The Paper: Since 2020, the novel coronavirus has become the object or point of writing for a group of writers. What do you think of it?

Moya: If writers don't have themes that stir up their internal organs and require them to write, then they will naturally go to contemporary reality to find themes, which is understandable. But I never wanted to write a novel about the epidemic myself, and I didn’t need to. After my experience settles down, I may write in the future. "Reality" is an intractable concept, which is why novels try to create their own reality, and the truth in novels is based on credibility, not the era they reflect.

Note: Zhang Tingting, the Chinese translator of "Crazy", provided translation assistance for this interview, and I would like to express my thanks.

Related Posts