The Paper learned that from July 5th, "chrome: Ancient Color Sculpture" will be held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met) in New York. The exhibition "restores" and reproduces the Sphinx in a primitive and vibrant form. There are 14 ancient Greek and Roman statues including faces, as well as more than 40 other ancient sculptures and pottery. They are in dialogue with ancient sculptures that have been polished to pure white by time in the bright and large exhibition hall of the Metropolitan Museum.

In the exhibition hall of the Metropolitan Museum, the color-reconstructed "Greek Woman" looks out of place among the white marble sculptures.

The colour reproduction of the "Sphinx" in the exhibition "Chroma" is the result of an extensive collaboration between the Frankfurt Sculpture Museum (Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung) and the Metropolitan Museum. Other reconstructions in the exhibition were created by the Frankfurt Sculpture Museum antiquarians Vinzenz Brinkmann and Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann, a husband-and-wife team. He has been researching color systems for more than 40 years, and his "Gods in Color" exhibition has been traveling since 2003, and his reproductions are collected by many museums.

The Sphinx from 530 BC (right) is on display alongside reconstructions in the Metropolitan Museum galleries

The exhibition title "chrome" is an academic term that means "five colors", especially when the sculpture is covered with oil paint. The exhibition showcases new discoveries of ancient color surviving in the Metropolitan Museum's collection, explores ancient color practices and materials used, and explores how color helped convey its meaning and how ancient polychromatic sculpture was viewed and understood in later generations .Rather than grouping these colorful reconstructions into a single exhibition hall, the Metropolitan Museum of Art is scattered throughout the museum's iconic Greco-Roman halls, and the scientific process by which the statue's true color is generated is illustrated through exhibition signs.

Sphinx, marble, ancient Greece, 530 BC

Take, for example, the "Sphinx," from 530 BC, which originally stood on the tall monument in the exhibition hall. It retains a large number of traces of yellow, red, black, and blue pigments, and there was a palm and scroll (spiral scroll) pattern on the top of the column. The "Sphinx" is a mythical creature that has appeared in various forms in Eastern Mediterranean art since the Bronze Age. The ancient Greeks depicted it as a winged woman as the patron saint of the dead, and its image is often seen on tombstones.Given that the original colors of the marble sphinx are relatively well preserved, through scientific analysis, photos in ultraviolet and infrared light, virtual color photos, and archaeological comparisons, it is possible to reproduce almost completely in bright and precious natural colors more than 2,500 years ago elegant design. Details where information is now almost lost, such as how to subdivide the feathers, may be the last step in the original painting process.

Greco-Roman Gallery, Metropolitan Museum, New York

For another example, Caligula was a Roman emperor in the 1st century AD. He was 25 years old when he ruled, but he died in an assassination after only 3 years, 10 months and 8 days in the reign. After that, his monumental sculpture was destroyed. Marble statues in the Met's collection record the image of the young monarch, but the scabs on their surfaces indicate that they were buried in a watery environment, and the marble surfaces are now well preserved. But Egyptian blue on the back has been identified by luminescence imaging technology, although its purpose is unclear, but usually Egyptian blue mixed with white and pink pigments was used for the flesh color of Roman figures; plus black, it was used for to represent shadows.

Marble bust of Emperor Gaius (Caligula), Rome, 37–41

The rich color traces were extensively analyzed by the researchers using a variety of scientific methods. The investigation found pink between the lips and lower eyelid, a mixture of iron oxide and chalk on the neck under the right ear, hair, eyelashes and pupils painted with charcoal black extracted from charred bone, which may have are traces of sketches on marble. Brinkmann also studied another portrait of Caligula in the Frankfurt Sculpture Museum's collection, and applied the faintly visible colors to the reconstruction of the Metropolitan Collection.

Caligula in the showroom

Color Reconstruction of Caligula

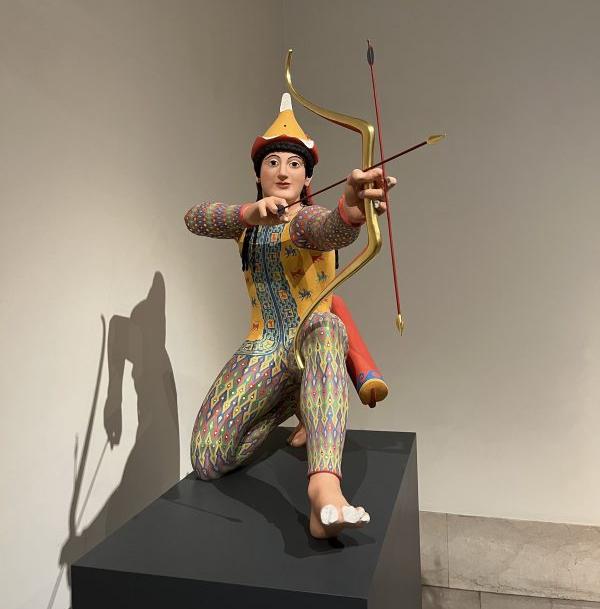

To determine the colors of the ancient statues, the Brinkmans combined scientific and art history research. For example, when reconstructing the ancient Greek archer statue, they used ultraviolet and oblique light to determine the patterns originally painted on its surface, and then used technical photography to see the color of the archer.They have since delved into art history for clues—a well-preserved Persian knight from the Acropolis helped the Brinkmanns determine the colors of the archers. After studying Greek pottery and Scythian textiles with patterns similar to the archer's clothing, the team also placed gold flecks on the replicas.

Greek Archer in Color Reconstruction of Team Brinkman

Seán Hemingway (grandson of the writer Hemingway), curator of Greek and Roman art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, believes that most ancient Greek and Roman statues bear traces of the original polychromatic origins of the ancient Greeks and Romans. In other words, the solemn white marble is not considered a finished draft, but a blank canvas. So why are these rebuilt, brightly colored statues so unaccustomed to viewers?

Fragment of a marble stele (tombstone) of an infantryman, Ancient Greece, c.525-515 BC

In fact, the white marble statue is a concept of the Renaissance. It is not known how this concept came into being. But during the Renaissance, sculptures with remnants of color were also found. And people of the Renaissance should also be able to read the relevant texts that mention the fact that there is color on the sculptures.

Standing Goddess, Ancient Greece, circa 525-500 BC

But during the Renaissance, an aesthetic standard of white antique marble was formed, which may have been the supreme visual code politically wanted to convey. The concept continued until the 18th century, when archaeologists excavated the ancient city of Pompeii with marble sculptures that were covered in lava and retained their colors. This makes people gradually change their understanding. In the 19th century, the issue of polychromacy began to be discussed openly because of public acceptance, but by the beginning of the 20th century, the issue of color on ancient Greek marble was somewhat suppressed, perhaps related to ideological tendencies.

Marble statue of a member of the royal family, Rome, 27 BC-68 AD

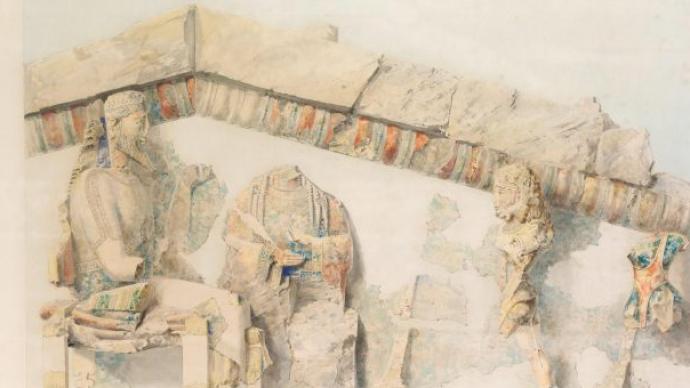

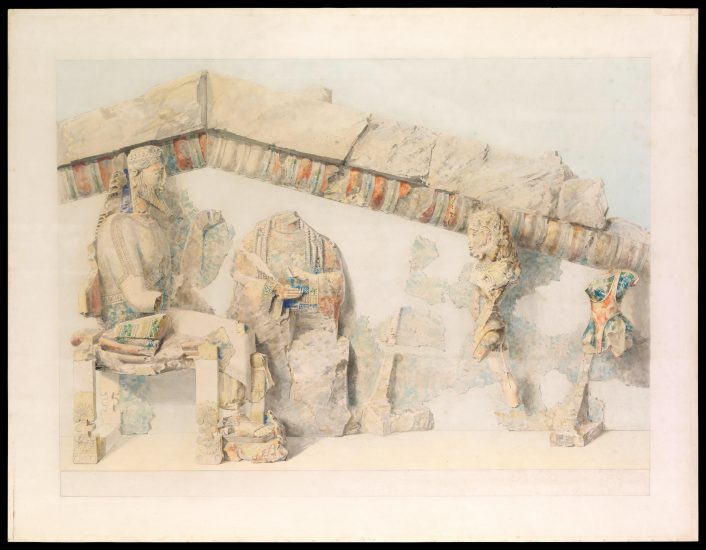

Although color has been studied in ancient sculpture for nearly half a century, Brinkman is certainly not the first to observe color in ancient sculpture. In a small room dedicated to the exhibition, a 1919 watercolor depicts the statue in the Acropolis after it was discovered, before it was exposed to sunlight.

Emile Guilléron (1850–1924) Watercolors of Limestone Sculptures on the Acropolis

Although, the colors of the replicas in the showroom made some visitors feel out of place. With extensive scientific explanations and lifelike reproductions, the Chroma exhibit sheds new light on ancient statues. "We believe that reproduction is the most powerful education in order to give the public a different perception. At the same time 'white purity' is a misunderstanding. Our research is a constant process of getting closer to the truth, we have no time machine and will never be able to find the complete the truth," Brinkman said.

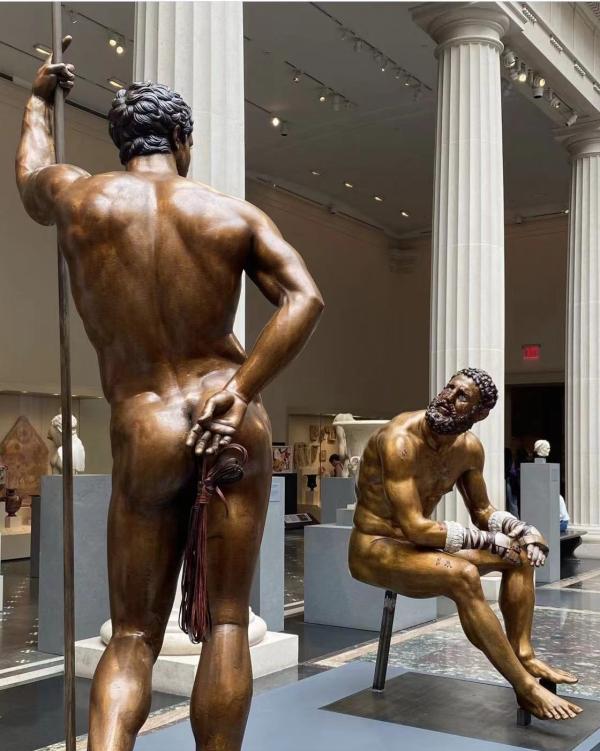

Brinkman's Reconstruction of Roman Quirinal (Boxer) and Other Bronze Statues

Perhaps the exhibition will finally change our perception of ancient sculptures - they are not pristine white, but colorful and vibrant artistic expressions. Note: The exhibition will run until March 26, 2023. This article is compiled from Hyperallergic Magazine, "The Met Brings Back the Colors of Ancient Sculpture" (Elaine Velie/Text) and the official website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Note: The exhibition will run until March 26, 2023. This article is compiled from Hyperallergic Magazine, "The Met Brings Back the Colors of Ancient Sculpture" (Elaine Velie/Text) and the official website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.