This year marks the 100th anniversary of the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb by Howard Carter and his team from England and Egypt.

However, the moment the Tutankhamun treasure was discovered, it became an active player in 20th-century politics, from the Egyptian government's struggle to maintain ownership of the tomb in the 1920s to the blockbusters of the 1970s and 1980s The exhibition contributed to the reconciliation between Egypt and the Western world. The British National Archives hold "Lord Carnarvon's Discovery" compiled by staff at the British High Commission in Cairo, which includes a large number of memorandums, letters and even intercepted telegrams related to Tutankhamun's tomb. The as yet unseen files show that the tomb is less a treasure trove than a diplomatic minefield.

Howard Carter and an unnamed Egyptian assistant inspect Tutankhamun's coffin in November 1922. Photography: Harry Burton; © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford

Carter's mud-brick house in Luxor is being restored a century after Tutankhamun's discovery; the $1.5 billion Grand Egyptian Museum, designed to fully reveal Tutankhamun's tomb, remains under construction.

But a hundred years ago, the controversy over the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb became a political hot water: the fate of the tomb was tied to the prospect of Egyptian independence and the reality of the withdrawal of the British Empire.

In 1922, Britain had effectively ruled Egypt for 40 years. However, since the 1850s, Egyptian antiquities have been supervised by the "Service des Antiquités" (Service des Antiquités), run by French archaeologists. This exception was so important to France that it was written into the fine print of the Anglo-French Entente of Amity (Anglo-French Entente) of 1904. In 1914, during the First World War, Britain declared war on the Ottoman Turkish Empire and announced the establishment of the "Egyptian Protectorate", deposed the anti-British Khedive, and supported another member of the royal family to become the Sultan. After the war, delegations seeking Egyptian independence were banned from the Paris Peace Conference, and its leader, Saad Zaghlul, was exiled to Malta after instigating anti-colonial demonstrations across Egypt. Egyptians who were dissatisfied with the British government launched riots in various places. In February 1922, facing a country in chaos, Lord Allenby, the British High Commissioner to Egypt, suggested unilaterally declaring Egypt's independence and establishing the Kingdom of Egypt. Sultan Fuad was promoted to king. However, Britain still has a certain influence on Egypt's domestic and foreign affairs, and it retains control of the Suez Canal Zone and Sudan. Egyptian artifacts, however, belong to the land.

Howard Carter and his patron, George Herbert, 5th Lord Carnarvon, were able to excavate and collect the treasures of Tutankhamun because Lord Carnarvon's wife, Almina Umberwell ( widely believed to be the illegitimate daughter of banker Alfred Rothschild) was French.

Lord and Lady Carnarvon at the racetrack in 1921.

Lord Carnarvon is confident the "magical stuff" in Tutankhamun's tomb will soon be his, as his excavations in the Valley of the Kings were carried out under a contract with the Antiquities Research Department which allows Sharing half of whatever he found (a 50-50 split between the digger and the museum was also standard practice at the time). But in semi-independent and nationalist Egypt, such generous distributions are coming under scrutiny. Lord Carnarvon quickly capitalized on his discovery, gaining practical support from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The Met sent archaeologist Arthur Mace and photographer Harry Burton to serve, and their photos of the tomb vividly showcased the treasures within. Carnarvon also signed a lucrative deal with The Times of London, which gave The Times exclusive access to the tomb for interviews and the use of Burton's photographs, forcing other media outlets, including local Egyptian newspapers, to demand The Times pays a fee to get the latest information, otherwise it only publishes old news.

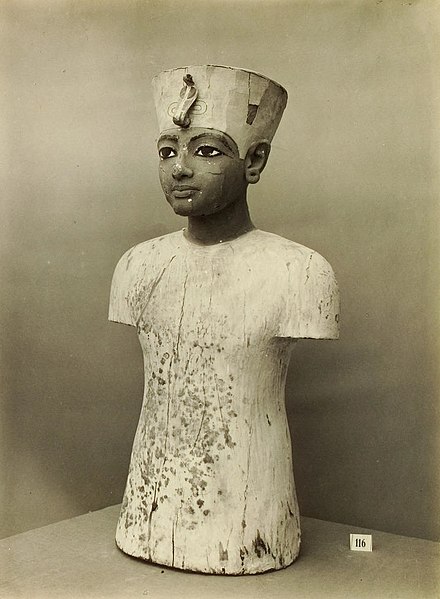

A painted wooden figure of Tutankhamun found in his tomb, photographed by Harry Burton

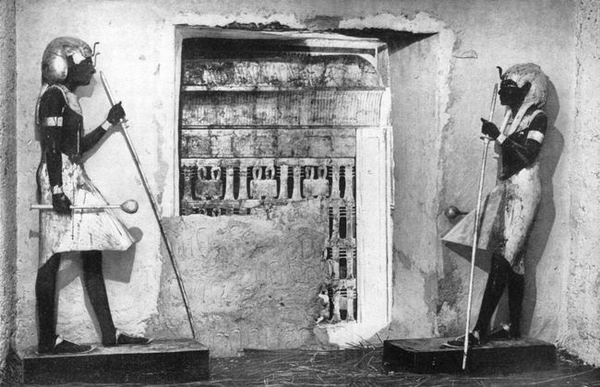

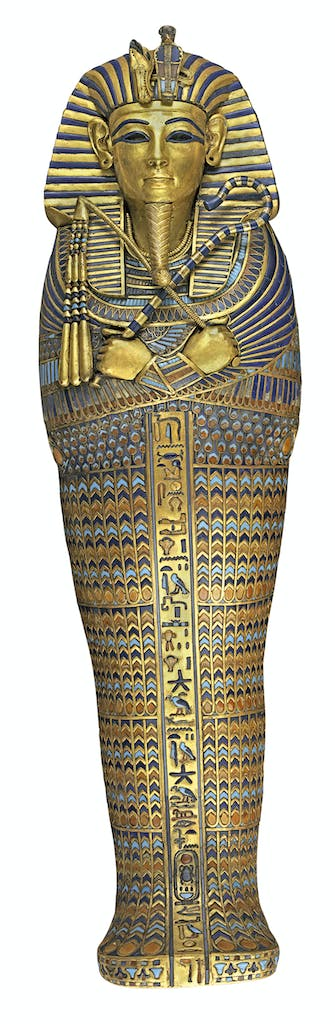

Lord Carnarvon and Carter snuck into the sealed chamber the day they entered Tutankhamun's tomb on November 26, 1922, but when the chamber was officially opened in February 1923, the pharaoh's mummy was surrounded by dazzling gilded Shrines and nesting coffins await its discoverer intact. A British lord who profited from the sale of news and photos of an ancient tomb will also get half of King Tutankhamun's funeral, angering many Egyptians and worrying the Ministry of Antiquities. Research director Pierre Lacau, who had long opposed private excavations of ancient tombs, had to acknowledge Carnarvon's excavation permit, and Carter's talent as an excavator was beyond doubt. The excavators and the research department discussed how to allocate around the "elephant" in the tomb. However, Lord Carnarvon's death in April 1923 sparked speculation about the pharaoh's curse, and while the widowed Lady Carnarvon continued to support the excavation, it meant Carter needed to deal with the government, the Department of Antiquities and the media, rather than His courteous patron. The political climate was also changing at this time, and Saad Zaghrul returned to Egypt from exile in September 1923 and led the nationalists to victory in the January 1924 elections. The "Pharaonism" movement (reviewing Egypt's pre-Islamic history as part of a larger Mediterranean civilization) was all the rage under Egypt's first post-independence prime minister, similar to the "Egyptian Awakening" (Nahdet Masr, A colossal granite sphinx and a peasant woman welcoming the dawn, the monument to the new pharaoh, links Egypt's independent future with its past. So, why do foreigners have the right to speak about Egyptian cultural relics?

Lord Carnarvon with his daughter Lady Evelyn Herbert and Howard Carter at the top of the steps leading to the newly discovered tomb of Tutankhamun in November 1922.

By the time Carter and his team planned to open the pharaoh's sarcophagus in February 1924, he had thoroughly alienated the Research Department, which complained to Lord Allenby (British Government High Commissioner to Egypt): "[Carter] grossly exaggerates It is an unsettling state of mind to speak of himself with the arrogance of a great European power over his contribution to Egypt.” So wealthy British Egyptologist Alan Gardiner lobbied the British Prime Minister Ramsay McDonald ordered Carter's contract to be canceled to prevent "piracy of the worst kind".

Lord Allenby scribbled in the margin of the memo: "I have never expressed an opinion nor expressed sympathy for either side. It is not worth doing anything." Another diplomat commented tartly: “At the bottom of the whole trouble there was a wicked jealousy.” The High Commissions (of the Commonwealth countries reciprocating) did what they could to avoid it: Carter was outraged that his collaborators’ wives were denied a private tour of the burial chamber, and he stopped The excavation left the ominous sarcophagus lid hanging over the coffin where the pharaoh's mummy was kept. The Department of Ancient Egyptian Antiquities immediately released Mrs. Carnarvon's contract; Carter sued for the right to establish the expedition; the Department of Research offered Mrs. Carnarvon a new contract on the condition that she renounce her claim to the contents of the tomb; Carter's Lawyers charged the Public Works Minister with treason years ago and smeared him for his current conduct, which led to a complete breakdown in negotiations. Carter left Egypt for a lucrative speaking tour of North America, but his future looked bleak.

Inside Tutankhamun's Tomb

If the political situation drove Carter out of Tutankhamun's tomb, then he was reinstated because of politics. In November 1924, Sir Lee Stark, the British commander of the Egyptian army, was assassinated by Egyptian students while driving through Cairo. Lord Allenby demanded huge reparations from Saad Zagrul's government, forcing Zagrul to resign. A pro-British government was then appointed. Alan Gardner saw his opportunity and wrote again to Prime Minister MacDonald:

Like all Britons, I deeply deplore this brutal murder which claimed one of the most illustrious and beloved servants of the British Empire. This event changed our policy towards Egypt and seemed to be favorable in many respects. ...

Allow me to venture to hope that in the coming months the claims of archeology will not be completely forgotten. All Egyptologists earnestly hope that justice will finally be done for their cause.

Although Macdonald's secretary turned him down again, this time Gardner's cynical assertion was not without merit. Because the new administration gave Carter a chance. The Antiquities Research Department knew that Carter was the best person to complete the excavation, and Carter also knew that the days of 50-50 splits were over. In negotiations for a new contract, Mrs. Carnarvon was promised to acquire some of the duplicate artifacts after the excavation, although stripped of any rights to the finds.

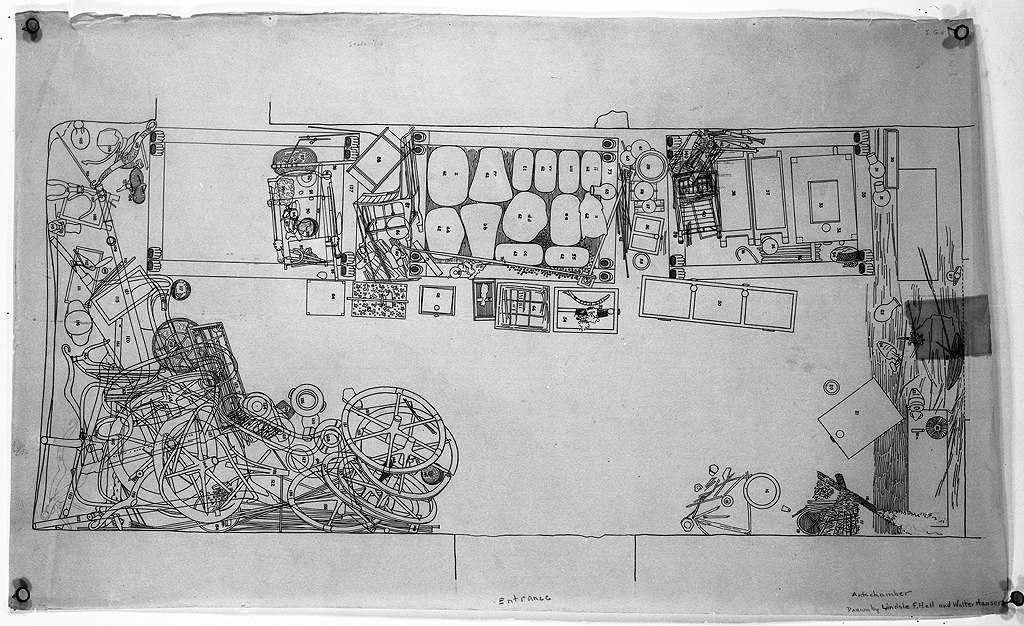

Plan of Tutankhamun's Tomb, by Carter

The 6,000 objects buried with Tutankhamun include hundreds of statues of Sapeti, dozens of gilded wooden deities and cosmetic ornaments, and six chariots. To this end Carter continued the painstaking work of cleaning the tomb until the High Commission (then headed by Conservative politician and Empire supporter Lord Lloyd) remembered Tutankhamun's tomb again. In the spring of 1929, when the mausoleum was empty, Carter and Mrs. Carnarvon pressed the Department of Antiquities to settle the accounts. But what can they expect from the Egyptian government? The previously promised "repeat" is gone, and the government has no plans to refund Mrs. Carnarvon's fees. Carter and Mrs Carnarvon estimated the cost at £75,000 (about £4m today), but the Egyptian government put it at £35,000.

Openwork gold memorial plaque from Tutankhamun's tomb, depicting Tutankhamun seated on a chariot. Cairo Grand Egyptian Museum

In April 1929, after a chance encounter with Carter, Lord Lloyd excitedly telegraphed the Foreign Secretary, Austin Chamberlain:

I have learned from first-hand and most confidential sources that an agreement between the Egyptian Government and Mrs. Howard Carter, representing Mrs. Carnarvon, is very likely. Their claim against the Egyptian government for Lord Carnarvon's discovery will be settled by a payment of money. ...

Lord Carnarvon was legally entitled to some "repeats," and it seems reasonable to expect something more than "repeats" as a token of gratitude for the great wealth that his discoveries conferred, directly or indirectly, on Egypt. I have been informed that the Egyptian government has decided not to surrender any of the artifacts to Madame Carnarvon and is confident that they will be sold quickly to the highest bidder.

I have come to the conclusion that if the British Museum or the government could stand up to represent Lord Carnarvon 's interests, it would be very difficult for the Egyptian government to refuse to give up "duplicates", which would be valuable collections in their own right.

If Mrs. Carnarvon can be persuaded not to make a fuss, Lord Lloyd thinks he can go to the Egyptian Prime Minister Mohamed Mahmoud to negotiate. Lord Lloyd's later telegram confirmed the dramatic proposal: Mahmoud agreed to the Egyptian government's sale of "replicas" of Tutankhamun's artifacts to the British Museum but rejected compensation to Lady Carnarvon.

Mahmoud instructed Pierre Racoud, head of the Antiquities Research Department of Ancient Egypt, to put aside a pile of duplicates and "provide the British Museum with the most complete and representative collection possible". These included at least one of the four golden canompus jars that contained the mummy of Tutankhamun's organs ("It may be suggested to Mahmoud that we should have two, one for the Met!" Lloyd added), Jewelry, a bench, a game board, gold statues and "a chariot or two". Lord Crawford, powerful in the British art world, was enthusiastic about Egyptian antiquities. He wanted the newly-elected Prime Minister Macdonald to give the British Museum a grant to buy the artefacts, and suggested that the British Museum choose ahead of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

One of four Canopic jars containing mummified viscera from the tomb of Tutankhamun (c. 1320 BC), in the Grand Egyptian Museum, Cairo

The last letter in the series was dated 18 July 1929, in which it was planned to invite representatives of the British Museum to assess the collection. At this time, Lord Lloyd was rushing to the UK to meet the new Foreign Secretary. Because his imperialist views were incompatible with the new Labor government, he was immediately asked to resign. Without support, plans to secure artifacts from Tutankhamun's tomb for the glory of the British Empire would die - and so would Mahmud's minority government, which had originally provided Tutankhamun's artifacts to maintain Britain's respect for Mahmud. regime support. A year later, the new Egyptian government paid Mrs. Carnarvon more than 35,000 pounds, she gave Carter a quarter, and everything seemed to be over.

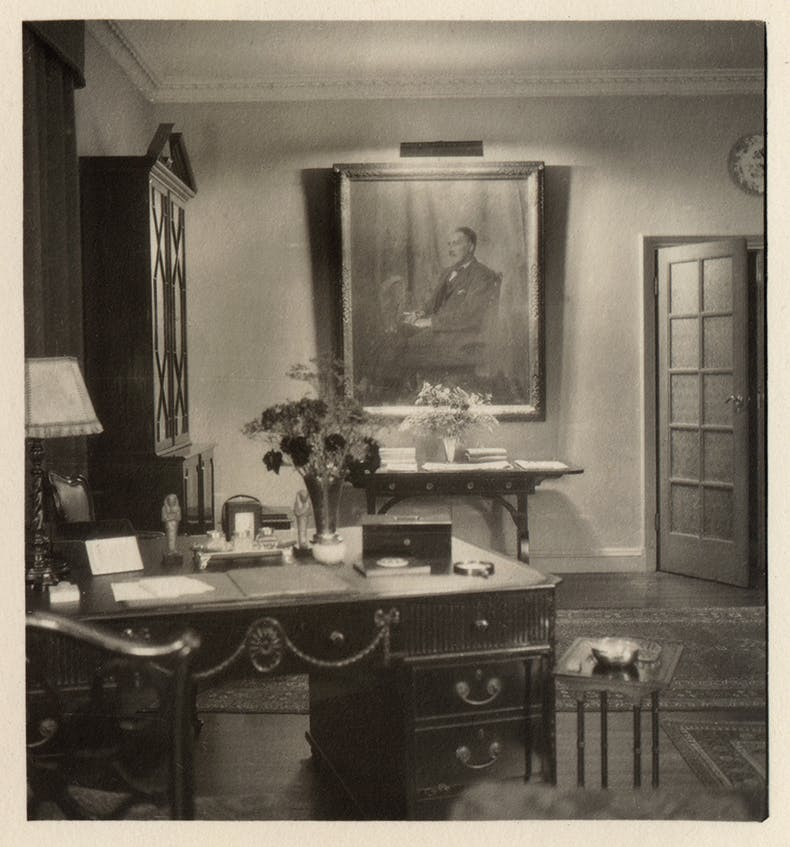

Carter's apartment in Kensington, London, photographed by Carter in the 1930s. Two Tutankhamun Shabiti statues can be seen on the table. Courtesy of the Peggy Joy Egyptology Library

However, after Carter's death in London in March 1939, Tutankhamun relics once again haunted the British Foreign Office. Carter's niece, Phyllis Walker, inherited his estate and soon found numerous objects inscribed with Tut's name in his Kensington flat. They could only come from the grave. Photos of Carter's apartment show two Sabiti figurines made of dark blue faience on his desk, while elsewhere there are faience vessels, openwork gold ornaments and a dark blue glass headrest with gold rims. Carter's executor, Harry Burton, investigates at the Egyptian Museum. British affairs manager Rex Engelbach was not impressed with Carter. He was chief inspector of antiquities in Luxor in 1922, but was out of town when the tomb was discovered. Out of courtesy and protocol, Carter and Lord Carnarvon had to wait for his arrival before opening the tomb, but they didn't. Engelbach complained to the High Commission that they deliberately downplayed the significance of the discovery so that the grave could be accessed without supervision. Burton's discovery came as no surprise to Engelbach. In November 1939, he wrote to the British ambassador, Sir Miles Lampson:

I've been skeptical for the past five years that Howard Carter didn't turn over everything he found to the museum, but my suspicions are based entirely on hearsay. There is nothing we can do because any official report will result in me and my department being sued for defamation.

This summer, Burton wrote to me that he had found two statues of Tutankhamun’s tomb among Carter’s belongings and asked me how to get them back to the museum. I replied that I would not touch that thing. Because I don't want to be taken advantage of in covering up an Englishman's theft. The best thing to do would be to throw that thing in the Thames, but I'll discuss it with my colleagues before making a definitive decision.

Burton advised Miss Walker to gift or sell them to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, claiming that the Egyptian government had not paid for the excavation. I don't know anything about it, and while I disagree with describing them as stolen, they cannot be considered Carter's property.

Engelbach proposed that if they could be returned to the museum, the Ancient Egyptian Antiquities Research Department would accept them anonymously as "possibly stolen from the excavation of Tutankhamun's tomb", but they must be placed in the British ambassador's office. sent to Egypt in the embassy's pouch to avoid customs checks. Will Sir Miles help?

Even in times of relative peace, British ambassadors and foreign ministers have bigger things to attend to. A scandal involving Tutankhamun's treasure would not only damage Britain's archaeological achievements in Egypt, but also Britain's wider interests and reputation. Myers referred the question to the Foreign Office. Two subordinates of Foreign Secretary Harry Fax added their advice to the document:

I suppose these things must be sent back to Egypt, though my personal inclination is to throw them into the Thames, as Mr. Engelbach suggests; The world disappears.

...

We're used to a "holier-than-thou" attitude towards Egyptians (not to mention other foreigners), so it was indeed shocking when we found out that a British antiquarian sometimes acted like a liar in Egypt. I see no reason for His Majesty's government to be involved in such a nasty affair. Miles Lampson needs to tell Mr Burton that the stolen item must be returned. There is absolutely no way we will condone any misuse of the official mailbag, nor am I prepared to suggest other forms of covert action in the hope that these precious artefacts will be illicitly smuggled out of Egypt — that hope is extremely slim.

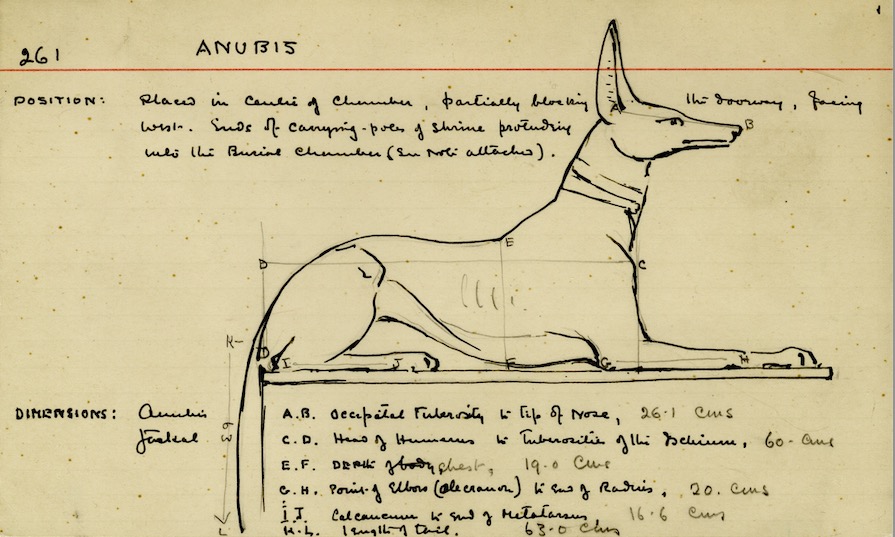

A record card by Carter showing his drawing of Anubis (the god of death in ancient Egyptian mythology who appears in pharaoh's tomb murals with the head of a jackal and a human body), with notes and dimensions. © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford

David Kelly, the Egypt affairs chief who worked in Cairo for several years and may have known Carter, was sympathetic:

By the way, I'm not sure it's entirely fair to call Mr. Howard Carter a liar. He has serious financial grievances with the Egyptian government (which has contributed nothing to the finds, which have greatly increased the interest of tourists, but which are currently intermingled with Cairo's ancient collections), and he may persuade I just got a little reward...

The potential damage from the revelations of the scandal is more of a concern than a discussion of Carter's propriety. Foreign Secretary Harry Fax's office instructed Miles to distance himself from the matter:

While I fully understand your concerns, I do not believe that His Majesty's Government will assist in the secret return of items taken by the late Mr Carter and now found among his belongings. Under the circumstances, I think there is only one course properly advisable, and that is to inform the executors of the late Mr. Carter to return the relevant cultural relics to their rightful owners as soon as possible.

Headrest from Tutankhamun's tomb. Cairo Grand Egyptian Museum

The files on Carter's and Lord Carnarvon's questionable estates were sealed after the Foreign Office turned their backs on the matter. Fortunately for estate heir Phyllis Walker, the Antiquities Department was also eager to cover up its own scandal. Pierre Lacourt's successor, Étienne Drioton, told her to leave Tutankhamun's artifacts at the Egyptian embassy in London, where they survived World War II. In 1946, it was delivered to King Farouk I of Egypt in an Egyptian diplomatic pouch. King Farouk quietly gave most of it to the Egyptian Museum, and Farouk kept Tutankhamun's amazing glazed head pillow.

The saga about Tutankhamun's tomb didn't end there, and its next twist came after a political upheaval. In 1952, Farouk was deposed in a coup, and his possessions - Fabergé jewellery, coins, banknotes, cars, antiques (some purchased on Carter's advice), snuffboxes, guns and more - were listed Auction catalog to support the Egyptian treasury. Artifacts from his collection, including the glazed headrest, were taken back to the Egyptian Museum, sending a signal that the new regime would not allow Egypt's past to be sold.

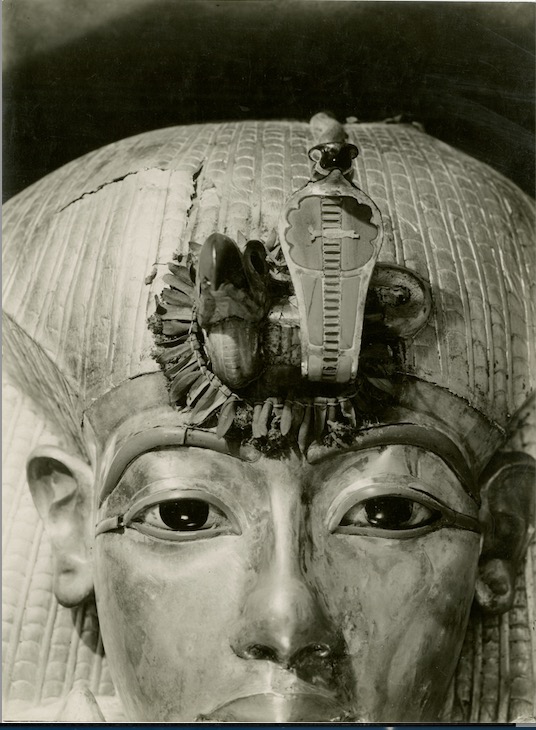

Small garlands of cornflowers and olive leaves are worn on the royal coat of arms of the cobra and vulture on the forehead of Tutankhamun's outer coffin. © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford

The government of Gamal Abdul Nasser and his successors used the treasures of Tutankhamun in another way. The cultural relics in Tutankhamun's tomb were "sent" to tour in exchange for support from other countries weights. Between 1971 and 1981, Tutankhamun's golden mask traveled longer than it stayed in Cairo. At the same time that major museums began to examine the history of their collections, the glass headrest was not the last item returned to Egypt from Tutankhamun's tomb.

Researchers examine Tutankhamun's coffin

In 2010, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York returned another collection. Further revelations that Carter may have taken items from the tomb continue to emerge as academics study Carter and Carnarvon's collection (Carter reportedly received a £5,000 commission through a middleman deal). Carnarvon also asked Carter about the grave-"I wonder if you will find more unmarked things", and this sentence has multiple meanings.

The Grand Egyptian Museum under construction.

Whenever the inauguration of the Grand Egyptian Museum takes place, it will surely be a triumphal celebration. Through the efforts of several generations, Egypt has established that the tomb of Tutankhamun belongs to Egypt.

Note: This article was originally published in the November 2022 issue of "Apollo Magazine" under the original title "Serious Questions - The Fight for Tutankhamun"