From the early 20th century to the present, "Hui School Printmaking", as an important topic in the history of Ming Dynasty printmaking, has received continuous attention from researchers. During this period, around the naming of the concept of "Hui School", scholars had a long discussion from the perspectives of the nature of engraved books, geographical divisions, and engraving functions. This article defines "Hui School" as a style of fashion, although it is closely related to the Huizhou book industry, but its cause, mode of operation, and time and space of streaming are beyond the single level of early discussions. As a unique landscape of the book industry in the late Ming Dynasty, "Huizhou style" is the core of a certain change in publishing orientation; through the appearance of print image style, we can even glimpse the propositions of class mobility and identity.

In the book prints of the Ming Dynasty, some highly recognizable images can often be seen, such as the common "upper picture and lower style" illustrations in Jianyang, northern Fujian, or the "moonlight version" in the Suzhou and Hangzhou areas. The particularity of this type of image is mainly reflected in the page layout arrangement. As far as the image itself is concerned-such as the content, structure, and style of the picture-it is rare to be called typical in the history of Ming Dynasty prints. The reason is that the ancient prints are different from the "prints" created independently by modern individuals. Most of them are attached to printed books, and they are drawn, transcribed, engraved, and printed by multiple people. In short, the ancient prints we are discussing are similar to all kinds of pictures produced by the assembly line of the modern book media industry, which are restricted by many factors such as publishers, editors, and readers. In the eyes of authors in the Ming Dynasty, engraved images were often associated with opera novels and stove horse playing cards, which belonged to "vulgar literature and art" that was difficult to be refined.

According to legend in today's bookstore, those who shoot profit are fake novels and miscellaneous books. Southerners like to talk about such things as Xiao Wang Guangwu of Han Dynasty, Cai Bojieyong, and Yang Liushi Wenguang, while northerners like to talk about such things as stepmother and great sage. Farmers, businessmen and traders, banknotes and paintings, livestock but people have them; demented women are especially fond of them, and those who are good at things are called "Nv Tong Jian", which is why. What's more, Jin Wang Xiuzheng, Song Lu Wenmu, Wang Guiling and other famous sages, even framed them in various ways, and used them as dramas as tools for drinking and entertaining guests. There are officials who don't think it is forbidden, and scholar-bureaucrats don't think it is wrong;

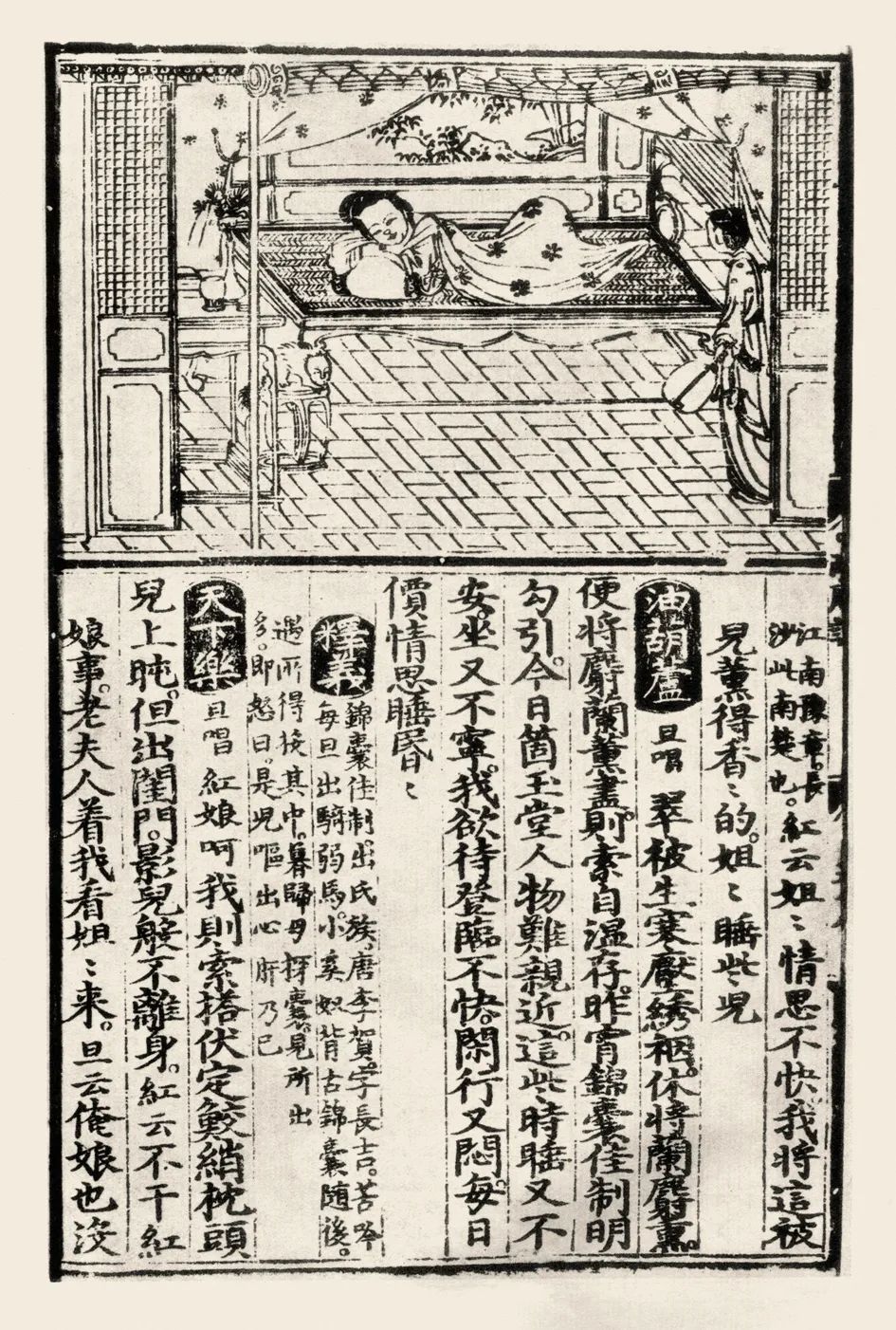

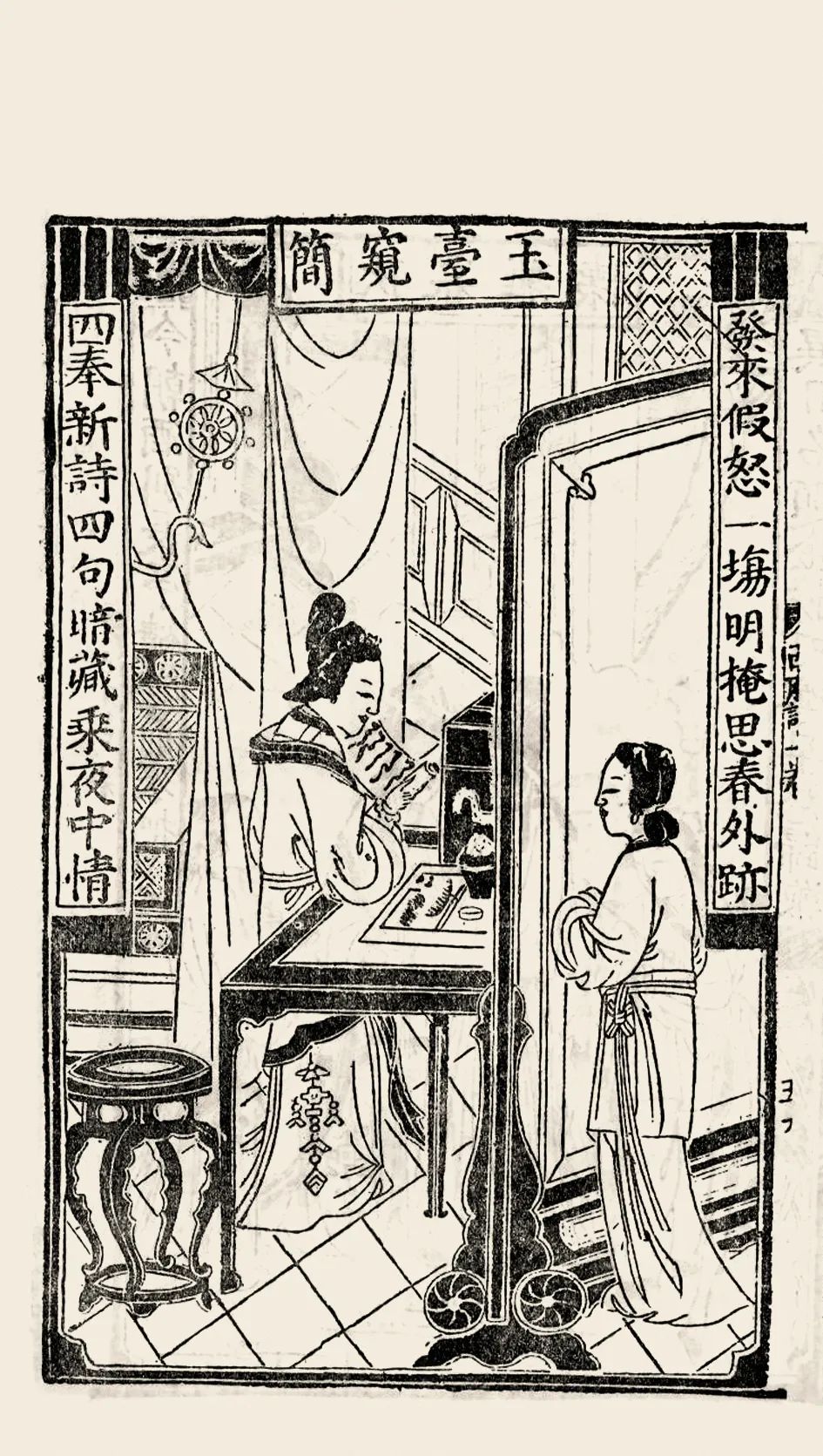

Figure 1 "The new publication of the big character Kui edition with wonderful annotations on the West Chamber" published by Beijing Jintai Yuejia in the 11th year of Hongzhi

This account by Ye Sheng (1420-1474) reflects the ambivalent attitudes of 15th-century scholars towards novels and opera readings as popular culture: they both acknowledge their influence and despise their superficial vulgarity. Popular novels originated from narration in the streets and alleys. Artists used rap skills and corresponding body movements to attract audiences. Therefore, early story books focused on storylines, with simple characters and rough writing. Things seem to have changed in the 16th century, though. As Shandong bibliophile Li Kaixian (1501-1568) said:

I have the disease of good books, and Zhishan Gezi is very dangerous. Isn't it the same disease and pity each other? However, scholars and bureaucrats are fond of novels, and the ancients have many books explaining the scriptures, which is not enough.

Jiaxing scholar Shen Defu (1578-1642) also recorded:

Yuan Zhonglang (Hongdao) used "Jin Ping Mei" and "Water Margin" as external canons in "Shang Zheng", which I hate to see. In the afternoon of Bingwu, when I met Zhonglang's mansion in Beijing, I asked if there was a complete copy. ... For another three years, Xiaoxiu (Yuan Zhongdao) got on the bus, already carrying his book, and returned home because of borrowing. Wu Youfeng Youlong (Menglong) was pleasantly surprised when he saw it, so he persuaded the bookstore to buy the engravings at a high price.

In the late 16th century, not only ordinary people read and copied novels, but also upper-level elites and officials. Printing and publishing novels has also become a custom. After collation, adaptation, and even re-creation by literati, novels that were originally oral cultures have been promoted to a literary style that appeals to both refined and popular tastes, and have also become texts for desk reading that do not rely on artist performances.

Quite similar to novels, Chinese opera was promoted from "village tricks" to urban written culture in the 16th century due to the participation of scholars. In the Song and Yuan Dynasties, zajus tended to be more popular with ordinary audiences. In the Ming Dynasty, most of the southern operas were created by literati. After the innovation of Kunqiang by Wei Liangfu (1489-1566) and Liang Chenyu (about 1521-1594), the northern operas were completely replaced by the legends of southern operas. In addition to teaching workshops and artists writing and performing themselves, more authors write scripts for self-entertainment or to communicate with their peers. For example, Shen Jing (1553-1610) and Tu Long (1543-1605) both had private theater troupes for entertainment. In the late Ming Dynasty, the function of literati drama was similar to that of pure literature such as poetry and ci, with an obvious elite circle color. Opera books, which are textual literature rather than oral culture, obviously target scholars with similar knowledge backgrounds. They are positioned not only as performance scripts, but also as elegant commodities with appreciation value. In the 11th year of Hongzhi (1498), which was slightly later than Ye Sheng’s life, the Jintai Yue Family of Jingshi Bookstore published "The New Issue of Big Character Kui Ben Can Zeng the Wonderful Annotation of the West Chamber" (hereinafter referred to as "Wonderful Annotation of the West Chamber"). There is such a text:

There are still many songs in the world, such as "The West Chamber", the best among the songs. Kuangluyan alley, recited by family members, and reenacted in plays, the words must be true, and the singing and pictures should match, and then it can be done. Today's publication in the market is intricate and incoherent. Although it means climbing the ridge, it is very inconvenient for people to view, and it loses the ancient system. Our workshop would like to rewrite the drawings according to the scriptures, and participate in the compilation of the large-character Kui version, singing and matching with the pictures. So that the guests who live in the guest house, travel in the boat, and sit on the boat can see it all the time, and sing clearly, which is refreshing.

Paiji belittles printed editions in the market and advertises its own products. It has a strong advertising meaning, but it also reveals the book engraver's positioning for illustrations: in addition to being used as a reference for opera texts, it must also have a certain appreciation value, so that readers will feel refreshed when reading and singing. . Although "The Story of the West Chamber" in "New Issue of Big Character Kui Ben Shen Zeng Miraculous Notes" follows the 14th-century Pinghua format of "upper picture and lower text", the content of the picture is far richer and more complex, and traces of the early stage setting have also been eliminated. (Figure 1) In the printed operas of the 16th century, the trend of engravings breaking away from the function of illustration and pursuing the value of appreciation is more obvious. Against this background, some "accidents" appeared on the huge book publishing line in the Ming Dynasty, and the prints, which were originally appendages to books, had the possibility of becoming independent "works".

What first attracted the attention of researchers were some prints that appeared in Huizhou in the middle Wanli period of the Ming Dynasty. They were mainly attached to printed copies of operas and novels, and most of them were narrative pictures. In the study, it will be discussed as "Hui School Prints". What is special about these prints is that they have an unprecedented sense of refinement and completeness, and are recognizable in image style, which is enough to leave a deep impression on the witnesses. Zheng Zhenduo, an early print historian and collector of ancient prints, described the characteristics of "Hui School" woodcuts in detail:

The layout is elegant and neat, the lines are delicate and well-proportioned, as small as the tip of a needle, as big as a landscape of splashed ink, firm and soft, suitable for everything. Rigid as an iron wire, soft as a gossamer. There is such a set of "scores" for the body and face of the characters. All the beauties have oval faces, like powdered jade shells, they are extremely beautiful to look at, if they are increased by one point, they are too long, and if they are reduced by one point, they are too short. The generals are mighty, and the civil officials are solemn and graceful. From the palaces of thousands of households to the thatched huts of the common people, they have all been beautified, like a paradise, with their own set of scores. Even the swirl of water waves, the unwinding of mountains and clouds, the ruggedness of strange rocks, and the branches of ancient trees all have their own set of scores. I can't tell the era, I can't tell the region, but from those "scores", there are thousands of wonderful things and scenes.

Zheng Zhenduo's text is beautiful and full of emotion. The main points can be summarized as follows: first, the layout is neat and the lines are delicate; second, the pursuit of ideal perfection; third, the shape follows a certain "score". Since then, researchers have further discussed the definition of "Hui School prints", and the main points include: 1. "Hui School prints" are defined as prints printed in Huizhou, or prints with the artistic style of Hui School; 2. "Hui School prints" 3. The style and characteristics of "Hui School Printmaking": elegant, rich, precise, and delicate; 4. The main influence of "Hui School Printmaking": promote the "Jian'an School" and "Jinling School" Pie" to a fine-grained style.

There are many disputes about the definition of "Hui School". In the past 20 years, the academic circle has gradually reached a consensus on the core role of book engravers in printmaking. In view of the fluidity of the book market in the late Ming Dynasty, it is not enough to divide the "genres" of printmaking by the place where the book is engraved; moreover, as a public commercial activity, book publishing is difficult to maintain a stable and introverted value appeal and creative concept like the literati painting school . The "Hui School" mentioned by Zheng Zhenduo and other scholars does not refer to the "Huizhou Printmaking School", but a certain printmaking style, and the decisive factor of this style comes from Huizhou. If this statement is true, we can call it "Huizhou style", and thus pay attention to the engraving event behind the style, that is, the rise of "Huizhou style".

As the name suggests, "Huizhou style" means a certain phenomenon, a certain fashion, and its specific manifestations are: Huizhou has become a new center of the book industry, Huizhou engravers are active, and Huizhou printed books are popular. This phenomenon arose from the surge in private publishing in the 16th century. In this regard, Jiangyin bibliophile Li Xu (1506-1593) had a real experience:

When Yu Shaoshi studied Juzi, he didn't have a manuscript for publication. There is a book Jia Zai Li Kao, and a friend's house, and the money is spent on dozens of papers, each of which is copied for 20 or 30 papers, and a few papers are selected in Yu's family school, and each paper is paid two or three papers. ... Now everywhere are engraved, and it is also a test of the elegance of the world.

Li Xu’s emotion from “no publications in the window” at the beginning of the 16th century to “everywhere is engraved” at the end of the 16th century is not an isolated case. His contemporary Tang Shunzhi (1507-1560) described the abundance of private printed copies from another angle:

For a butcher who has a bowl of rice to eat, there must be an epitaph after his death; for those high-ranking officials and nobles who have a little name in the world, there must be a collection of poems and essays after death... Fortunately, the so-called epitaphs and anthologies of poems and essays will soon disappear, but those that passed away are gone, and those that remain are still full of houses. If they all exist in the world, even if the earth is used as a shelf, they will not be able to settle down.

The ease of obtaining printed books stems from the reduction in material and technical costs, such as the widespread use of cheap bamboo paper produced in Jiangxi and Fujian and the reduction in production costs brought about by the modularization of book engraving processes; at the same time, it also benefits from the The literacy population expanded and the demand for books increased. However, the more profound social changes in the 16th century were the rapid development of the commercial economy and the changes in social class and consumer culture brought about by it. Traditional social class boundaries became loose, and businessmen began to pursue things that belonged to the elite by virtue of their wealth advantages; literati used their poetry, calligraphy and painting skills to win the employment and sponsorship of the rich:

Fengzhou Gong (Wang Shizhen) and Zhan Dongtu (Zhan Jingfeng) were in Waguan Temple. Fengzhou Gong even said: Xin'an Jia people see Suzhou literati, like flies gathering together. Dong Tu said: Suzhou literati see Xin'an Jia people, just like flies gathering together. Duke Fengzhou smiled but did not answer.

Wang Shizhen (1526-1590) and Zhan Jingfeng (1532-1602) joked about Huizhou businessmen, which can be regarded as a typical group of scholars and merchants in the late Ming Dynasty. In the late 16th century, Huizhou merchants were the first to be the "rulers of the rich". Different from ordinary business gangs, Huizhou merchants spend more of their wealth on art collections, culture and education, as well as making friends with officials and donating fame, which reflects the tendency of businessmen to become officials. Ideal way. Ordinary commercial bookstores focus on making profits, and the consideration of cost and sales is the first. For Anhui merchants who got rich in salt, tea, and wood, they engaged in engraving books more to seek cultural identity recognition. Books are not stingy about cost, pay attention to taste, and show a clear literati orientation. The rise of engraved books in Huizhou during the Wanli period was due to factors such as geography, materials, and engraving techniques, but the most critical driving force came from the participation of literati booksellers. The emergence of these Huizhou "Confucians and Jia" has greatly changed the development trend of late Ming book prints, and because of this, the academic circles have discussed them as "Hui School prints" for a long period of time, and paid special attention to them .

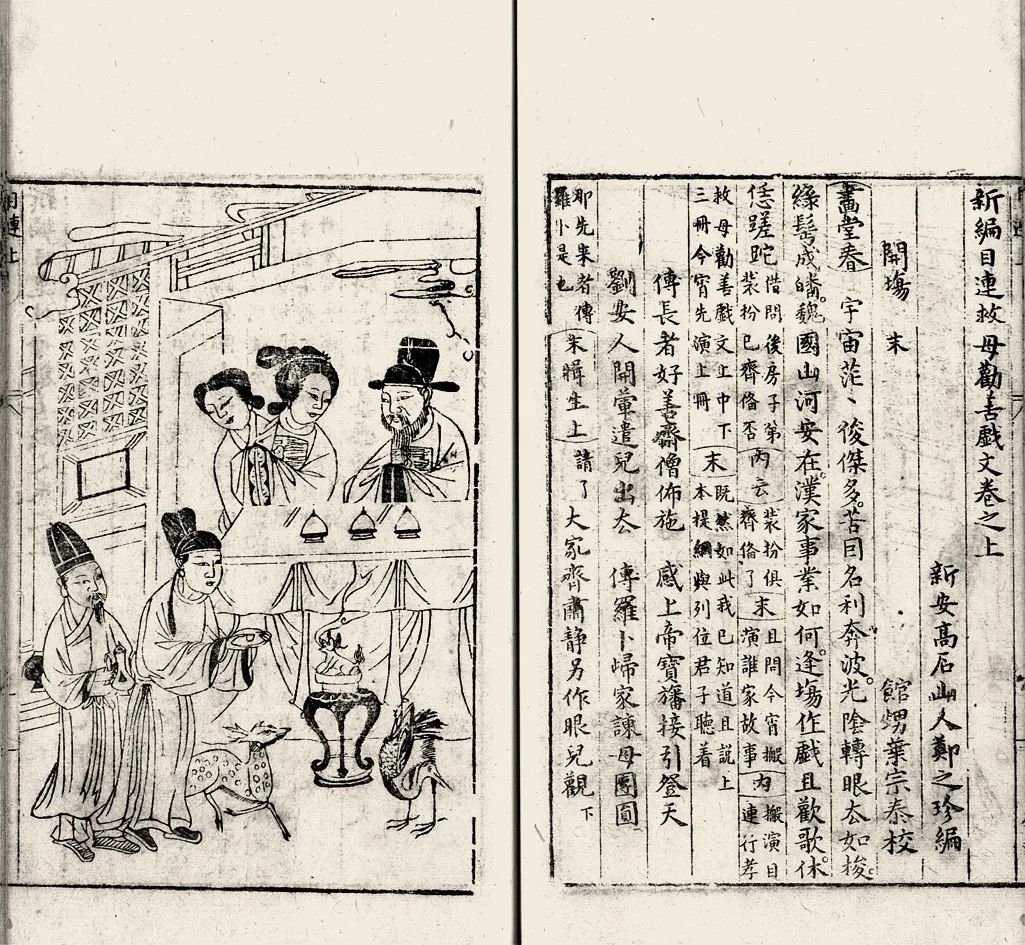

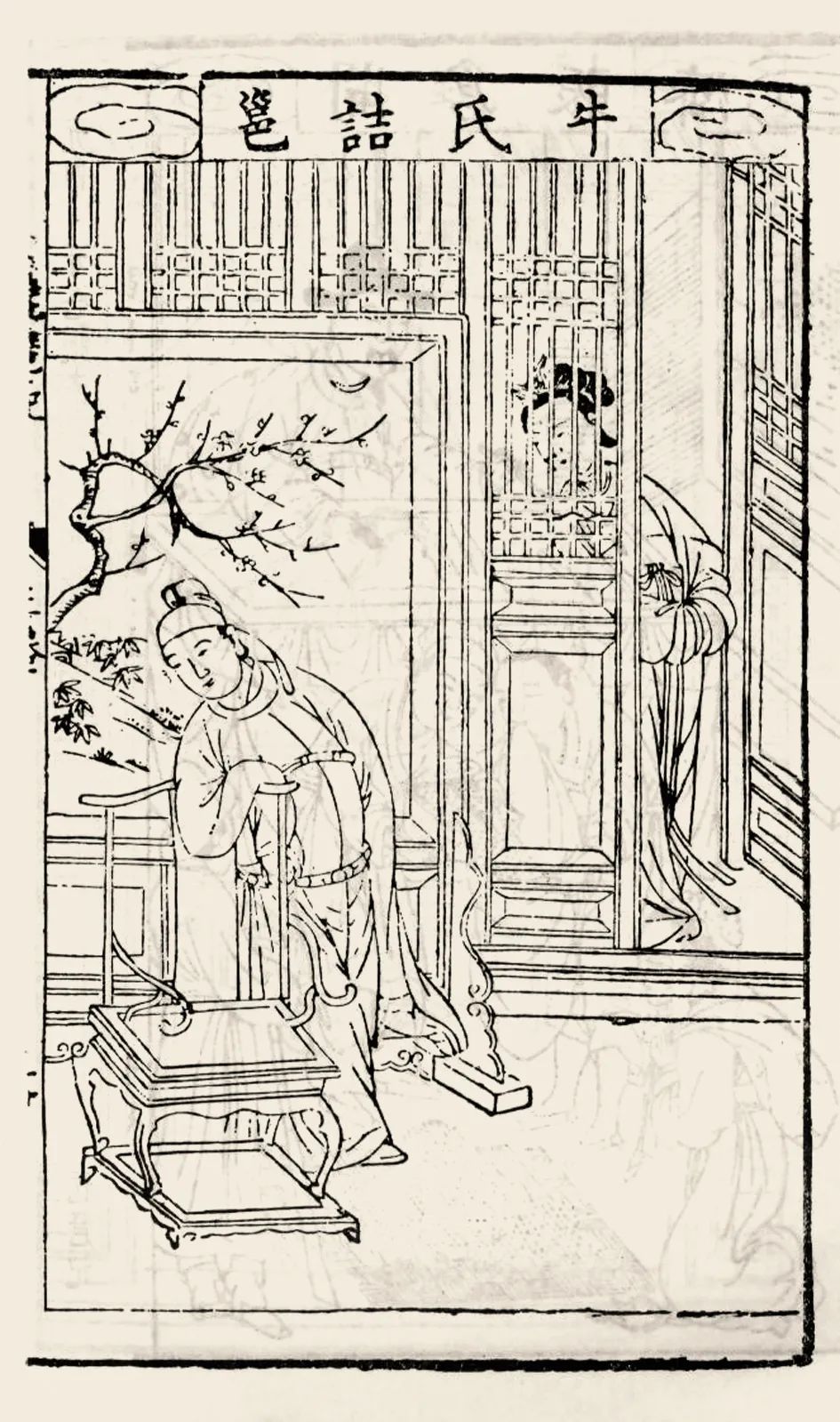

Figure 2 "New Catalog Lian Rescue Mother and Encourage Kindness Plays" Anhui Museum

Early scholars generally believed that "Hui-style prints" began with the "New Catalogue Lianjiumu Encouraging Good Play" (hereinafter referred to as "Mulian Jimu") published by Zheng Zhizhen's Gao Shishanfang in the tenth year of Wanli (1582), and the Hui edition has been since then. Gradually get rid of rough and simple, and tend to be beautiful and delicate. This conclusion is obviously influenced by the concept of "carver center", because it is the earliest work of Huang's carver in the Wanli period. Zheng Zhizhen was a native of Qimen, and was born in the Ming Dynasty. His life history is unknown, and his inscriptions are unknown. However, the paper, typesetting, and text content of "Mulian Rescue Mother" all reveal the obvious color of mass reading, and its readers are likely to be middle- and lower-class people. The characters in the prints are also similar to folk New Year pictures, with simple and hard lines, overcast lines and ink block color blocks, and the scenery is roughly expressed. (Picture 2) This kind of picture effect is far from "workmanship and delicacy", and it is quite contradictory to regard it as a representative of "Hui School". It is worth mentioning that scholars followed this line of thought and summarized the prints of other regions into a certain style, such as "Jinling School prints" as "vigorous", and "Jian'an School prints" as "quaint and naive", which also concealed the geographical scope. stylistic diversity within, as well as dynamic changes over time at the individual level.

Recent research shows that by the middle of the seventeenth century at the latest, the book trade in southern China had been virtually integrated. As we can see, the names of the same writers, editors, and engravers repeatedly appear in printed books in different regions, and publishers and craftsmen with different origins travel and live in various cities in the book publishing network. In the second half of the 17th century, the competition and "resource sharing" among the book industries in Jiangnan, Huizhou, and Fujian may have gone far beyond our imagination. For a bookstore with limited funds and targeting low-end consumers, the Jianyang Printed Edition in Northern Fujian is an ideal imitation object. Among these printed copies, which are aimed at ordinary people, do not avoid slang, and are close to daily needs, one often sees a kind of "simplified" prints. Its characteristics include: 1. The prints are mainly used to interpret words, mainly the above pictures and below, There is also a single-sided method; 2. The composition is not fixed, the spatial level is simple, or it presents a stage-like flat depth of field effect; 3. The background is mostly blank, with fewer decorative patterns, and there are obvious traces of the stage in the set decoration; 4. The drawing and carving are simple, Yang lines and Yin carvings are used together, and the lines are less varied; 5. The movements of the characters are exaggerated and pretentious, often presenting a "show" posture on the stage, without obvious emotional portrayal.

Most of these prints are in Jianyang printed editions, and they appeared earlier, which can be called "Jianyang style". However, the existence and spread of this style is not limited to Jianyang. In the Wanli era, each book industry center selected a corresponding publishing model based on market factors such as materials, labor, and transportation. At the same time, due to personal reasons, book engravers also adopted publishing strategies that "escaped" from the current model, such as Jianyang engravers such as Liu Longtian, Yu Zhangde, Jiang Yunming, and Yu Shaoya all tried layout schemes different from the "Jianyang style" in their printed copies. As for printed editions such as "Mulian Saves Mother", they actually adopt the Jianyang style of publishing. It was not until more than 10 years later that Huizhou book industry shed the influence of Jianyang and established a new model of book engraving due to the participation of literati engravers. Among them, the Wanhuxuan Bookstore of Wang Yunpeng from Shexian County has played an important role in pioneering and leading the evolution of the style of book prints.

An unusual feature of Wanhuxuan's products is that the text content and drawing style are relatively fixed. "Yangzheng Diagram" published in the twenty-fifth year of Wanli (1597) is an exhortation reading compiled by Jiao Hong (1540-1620), who was a lecturer in the Eastern Palace, for the eldest son of the emperor. This book is a collection of allusions to characters from the Western Zhou Dynasty to the Song Dynasty. There are 60 biographies in total. Each biography has a picture. With such a "production team" and its results, "Mulian Rescue Mother" is naturally not in the same breath:

Between Yiwei and Bingshen, Hou Hong, the eldest son of the emperor, was a lecturer for the eldest son of the emperor, and wrote "Yangzheng Tushuo" which entered the Eastern Dynasty. …Since it was carved by people from Huizhou, the pear jujube is exquisitely crafted, and its portrait was made by Ding Nanyu, a famous Xin'an scholar, and it is even more flying like life.

An important reason for the great success of "Yang Zheng Diagram" is that the prints have achieved an unprecedented level of delicacy and elegance. Compared with the brevity and crudeness of "Jianyang Style", the illustrations in "Yangzheng Diagram" are composed of continuous and fine lines, just like those drawn with a brush. Not only the sharp "knife taste" completely disappeared, but also various details, such as horses The mane of the mane and the decoration of the clothes are all carved out tirelessly. This significant change in printmaking is directly related to the participation of famous craftsmen, but it is fundamentally due to the difference in the publishing orientation of bookstores. Choose books with serious themes, use famous artists like Ding Yunpeng as signs and imitation objects, and polish beautiful and fine woodcut images, which are extremely rare in the past.

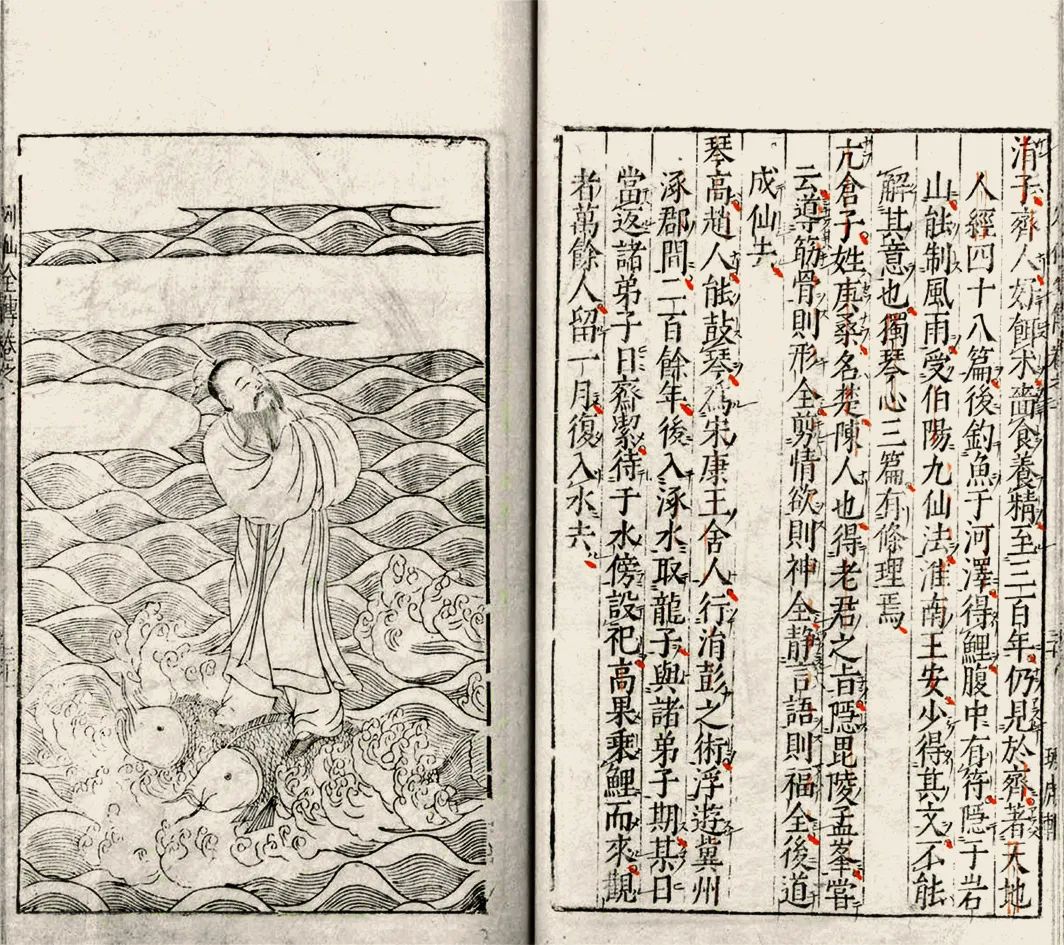

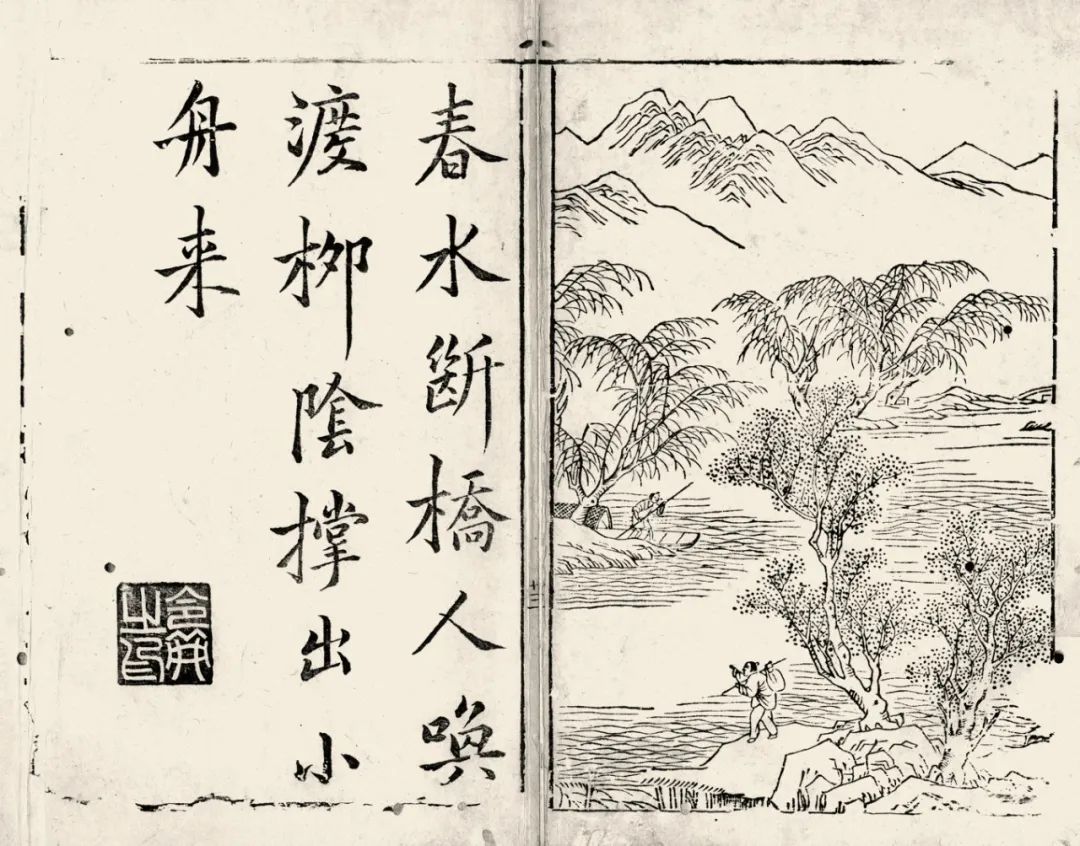

Figure 3 "Pipa Records of Yuanben's Appearance" National Library of China National Library of China

In the same year, Wanhuxuan published "Yuanben Chuxiangxixiangji" and "Yuanbenchuxiangpipaji" which were also all the rage, and soon became the targets of imitation and plagiarism by other bookstores. Two volumes of "The Story of the Western Chamber in Yuanben", a total of 20 pieces, each with a picture, engraved by Huang Yu and Huang Yingyue, and the small portrait of Yingying at the beginning of the volume signed by Wang Geng; three volumes of "Pipa in Yuanben", with 28 pictures , those not signed and drawn, were engraved by Huang Yikai and Huang Yifeng (Figure 3). The text content and visual form of these two opera books continue the elegant and refined taste established by "Yangzheng Diagram". Not only that, but the 48 illustrations in the two books have been changed to double-page linkage, which has reached a perfect state in terms of visual pleasure and poetic creation. The "Romance of the West Chamber", "The Story of the Pipa" and another "The Story of the Red Fu" chosen by Wang Yunpeng were all classic texts at that time. It is to produce high-quality goods that are enough to impress scholars and readers and demonstrate their own brand value.

Figure 4 "The Complete Biography of You Xiang Lie Xian" published by Huxuan in the 28th year of Wanli

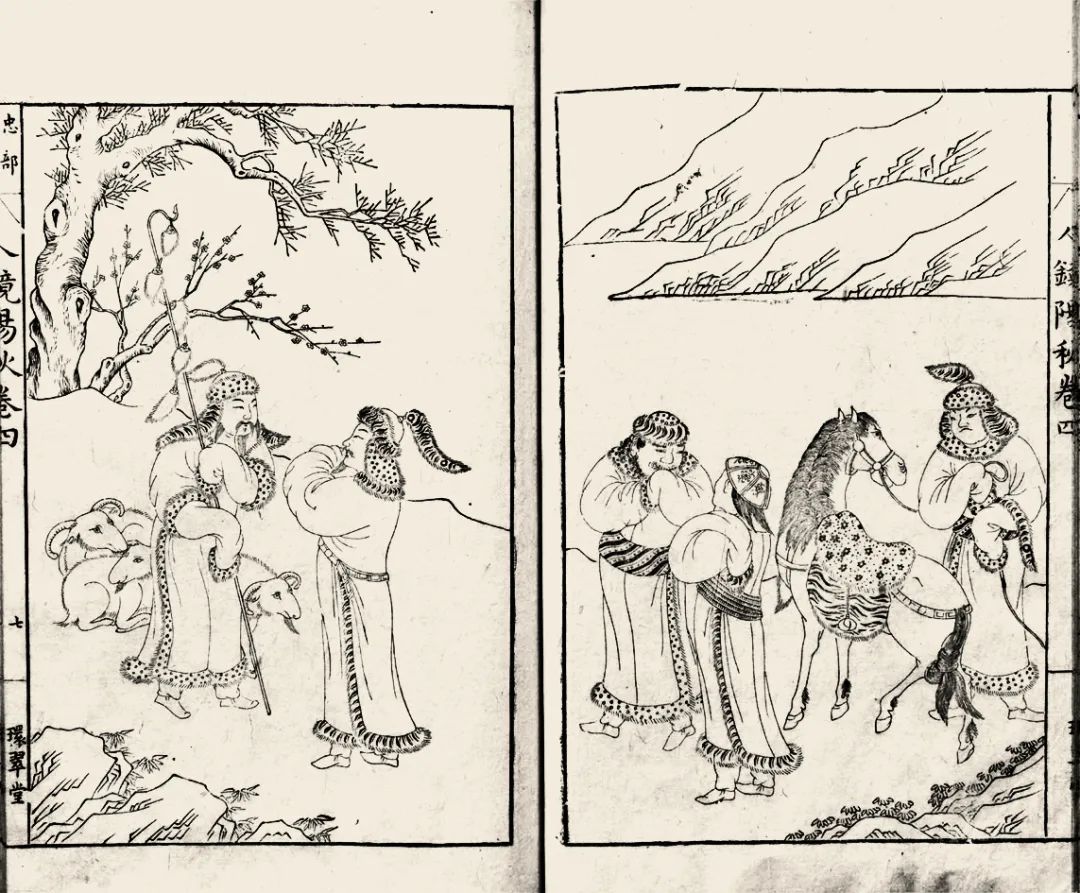

There is no biographical information about Wang Yunpeng, we can find out from the related printed copies and the information of the engraver. In the twenty-eighth year of Wanli (1600), Wang Yunpeng published "The Complete Biography of You Xiang Lie Xian", a total of nine volumes, including 581 Taoist gods from ancient times to the end of Hongzhi, with 222 attached pictures, single-sided, Huang Yi woodcut (fig. 4). No matter the subject matter or scale, this book is very reminiscent of "Human Mirror Yang Qiu" published by Wang Tingna, a native of Xiuning at the same time. The latter consists of 22 volumes, which describe the role models of the past dynasties. Each story is accompanied by a picture, a total of 358 pictures, double-sided, drawn by Wang Geng and engraved by Huang Yingzu (Figure 5). The text structure and illustration style of "Renjing Yangqiu" and "The Complete Biography of Youxiang Liexian" are quite similar. Not only that, the six-page "Zuoyin Yipu" in another printed edition of Wang Tingne's "Zuoyin Yipu" "Picture" also uses the combination of Wang Geng and Huang Yingzu. If you compare "The Story of the West Chamber", "The Story of the Pipa" and "The Story of the Red Fu" published by Wanhuxuan, you can find that although the layout of these illustrations is different, the style is exactly the same.

Figure 5 "Huancuitang Printed Edition" in the twenty-eighth year of Wanli, Shanghai Library

Wang Geng is undoubtedly the key figure in the drawing of the above-mentioned prints. Although he has cooperated with Wang Yunpeng and Wang Tingna many times, there are only a few prints with clear signatures; the rest can be roughly divided into two categories based on the pictures: one is highly similar in style, It is very likely that it was written by Wang Geng, such as Wanhuxuan's "Red Fuji" and "Yuanben's Story of the Western Chamber" published by Cao Yidu Qifeng Museum in Hangzhou in the 38th year of Wanli (1610); another type of overall effect is similar. But the details are obviously different, which belongs to the imitator of Wang Geng's painting style. The latter type of "imitation" is widespread in the book market in southern China, which shows how popular this image style was in the book market from the end of the 16th century to the early 17th century. This style generally has the following characteristics: 1. The layout is mostly double-sided, and there is also a single-sided format, presenting a complete picture and narrative plot; 2. The composition is clear and the scenery is realistically depicted, basically eliminating the stage-like space effect ; 3. The shape is purely Yang line, without ink background, incised, round and smooth lines, rich in details, and densely decorated; 4. The figure is slender, with a gentle and reserved posture, even if it shows conflicts and conflicts, there is no sense of tension; 5. Facial expressions are stylized, most of them are "full of heaven, square of ground, arched eyebrows, and eyes like tadpoles", and their expressions seem to be smiling but not smiling; some details, such as the shape of trees and horses, still retain the traces of folk prints .

This is undoubtedly a very typical and recognizable image style. According to its source, it can be called "Huizhou style" or "Wang Geng style"; compare the "Huizhou style" prints described by scholars such as Zheng Zhenduo and Zhou Wu style, it's not hard to find consistency in it. However, the Huizhou style is the product of the specific intention of the book engraver, and it is difficult to simply use the region as a static classification standard; Nanjing and Hangzhou may also have the Huizhou style, and small-cost bookstores in Huizhou may also choose other styles.

From the description of the above characteristics, it can be seen that the Huizhou style is actually a rather stylized language. Zheng Zhenduo's "music book", that is, the ancient painting samples and powder books, should be referring to this point. As discussed by Redhout about the widespread "modular" modeling in Chinese art, although literati painters despise modular products, they still follow the principle of modularity when organizing compositions and arranging scenery. In the system of folk painters, this principle becomes more specific and easier to operate, and it is matched with the corresponding motif. Interestingly, some of these criteria are quite close to the visual characteristics of the Huizhou style:

Beauty appearance: nose like guts, melon-seeded face, small cherry mouth and grasshopper eyes; walk slowly, don't slap your hands, and don't open your mouth when you want to smile.

Lady-like: Eyes upright and happy, calm and brow relaxed. Walk slowly, sit like a mountain.

Maid-like: with high eyebrows and charming eyes, with a charming smile, biting her fingers and flicking a towel, sweeping her temples and finishing her clothes.

Look like a nobleman: with eyebrows drawn into the temples, energetic eyes, and steady movements, you are a nobleman.

In an ingenious way, Huizhou-style authors realized the "image conversion" from individualized brush and ink to uniform components, from referential things to all-encompassing systems. For example, the halls, rocks, chariots, horses, and vegetation in Wanhuxuan's version of "The Story of the Pipa" can all be moved to the illustrations in "People Mirroring Sunshine Autumn" or Qifengguan's version of "The West Chamber", and appear in a new combination. Even the images of the characters can be reused with only minor changes. The tens of thousands of scholars, couples and children with different appearances in the printed books of Wanhuxuan, Huancuitang, Qifengguan and other bookstores all have almost the same faces, and the clothes of the characters do not seem to be wrapped in real bodies. , but a mass of weightless air. These pretentious pictures bring us a special sense of beauty, as if we are living in a clean and beautiful world that does not eat human fireworks.

These engraving books of Wanhuxuan show the characteristics that were rarely seen in commercial publishing before: first, Wang Yunpeng’s book engraving business adopts a "high-quality" strategy, and its audience is likely to be scholars and intellectuals; Second, Wang Geng's style (including Wang Geng's style imitated by many unknown painters) is the image style selected by Wang Yunpeng to continue to appear in his products; The delicacy of the engraving quality and the consistency of the image style; Fourth, the prints in the printed version of Wanhuxuan have basically broken away from the graphic and subordinate functions, and have independent appreciation and brand building value. This is also an important factor for the fame of Wanhuxuan Bookstore.

In a short period of time, a group of similar literati bookstores appeared in Huizhou. For example, Cheng Junfang’s Zilan Hall, Fang Yulu’s Meiyin Hall, Wang Tingna’s Huancui Hall, and Xie Zixu’s Guanhuaxuan all use literature and appreciation books as the main themes, and employ famous craftsmen to create exquisite prints printed copy. Wang Tingna, like Wang Yunpeng, chose the painting and engraving team of Wang Geng and Qiucun Huang, and maintained a stable continuity in the volume, shape, layout, font, and illustration style of the book.

Regarding the influence of Huizhou style, a common view in the field of print history in the late Ming Dynasty is: under the influence of "Huizhou School", the "Jinling School" has undergone a change from rough to fine. This point of view is still due to the way of thinking that divides the printed copies of Huizhou and Nanjing into two. As for the interaction between the book engraving centers in the Yangtze River Basin in the late Ming Dynasty, conclusions cannot be drawn based solely on the comparison and analysis of images. That is to say, in terms of prints, Nanjing and Huizhou are not a simple relationship of influence and being influenced, and the situation of individual bookstores varies greatly, let alone generalize.

In fact, the exact opposite may be true. As the upper reaches of the market and the central city of the region, Nanjing has an all-round influence on the commercial culture and social customs of Huizhou on the edge of the "Jiangnan". Although the rising Huizhou has not fallen behind in terms of book quality and marketing methods, in the eyes of Huizhou merchants, the superiority of prosperous cities like Nanjing and Hangzhou in terms of cultural identity and consumption methods is not only difficult to eliminate, but also irresistible. attraction. Many Huizhou engravers set up bookshops in Nanjing at the same time, traveling between the two places. In the 17th year of Wanli's reign, Shidetang's publication Nanjing book industry has several notable characteristics, namely, huge consumption volume, diversified market, popular scholar culture and exquisite life taste. Since it is different from Jianyang, Huizhou and other book engraving centers with a relatively single publishing orientation, it is impossible to generalize Nanjing's commercial publishing into a certain model. Previous studies mostly defined the style of the "Jinling School" as "rough and bold" and "vigorous". For finely printed prints, it was explained that they were influenced by the "Hui School", and then changed from "rough" to "fine". Such an explanation belongs to the same type of misunderstanding as the concept of "Hui School". It is not difficult to see from the existing prints that the so-called "Jinling School" prints do not have a convergent style. If you compare them again, you will find that not only are the prints of different bookstores different, but even the same bookstore has very different product appearances in different time periods.

In fact, the "Jinling School" style described as "vigorous" and "thick" is mainly a kind of printmaking pattern commonly seen in the printed books of Sanshan Street Bookstore, among which Tang Duixi Fuchuntang is the typical representative. It can be summarized as follows: 1. The layout is mostly single-sided, with titles and headings attached; 2. The background arrangement is simple, and the movements of characters and scenery have a strong sense of the stage; Towel hats, hair buns, masonry, etc. are represented in ink, with a sharp contrast between black and white; 4. The characters are prominent, most of them are taller than half of the picture, and their postures are stiff, lacking a sense of reality; 5. The facial processing is stylized, with Obvious traces of folk art, no further emotional expression.

Figure 6 "The Story of the White Snake Published in Newly Published Image and Audio Annotation" published by Fuchuntang in Wanli

Figure 7 "Republishing Yuanben Title Commentary and Interpreting the Story of the West Chamber" published by Qiao Shantang in Wanli

Such a "Jinling School" style is actually quite similar to the Jianyang style. Judging from the text themes, publication costs and appreciation tastes of Sanshan Street Bookstore products such as Fuchuntang, their publishing belongs to a standard business model, and their target audience should be ordinary scholars and citizens. However, slightly different from the Fujian area, the "Jinling School" style is more like a manifestation of folk figure painting styles since the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Mainly based on the line drawing of Yang lines, supplemented by the method of engraving on the ink background, the book prints in the 12th century, such as the engraved version of "Three Ceremonies" in Zhenjiang in the second year of Chunxi in the Southern Song Dynasty (1175) and the "Picture of Three Ceremonies" published in Jin Mingchang (about 1190) It has been widely used in the Supplementary Notes of Bronze Man Acupoint Acupuncture and Moxibustion Illustrated Classic in the new issue. In popular readers for ordinary readers, the characters are often more simple, direct and symbolic. For example, during the Chenghua period (1465-1487) Beijing Yongshun Shutang's "Bao Long Tu Duan Cao Guojiu Gongan Biography", Wanli Nanjing Fuchun Tang's "Newly Published Image and Audio Annotated White Snake" (Figure 6) and Jianyang Qiaoshan Tang's edition The illustrations (Fig. 7) of "Republishing Yuanbenti Commentary and Interpretation of the West Chamber" show the characters and settings as if they came from the same production team. As mentioned above, the visual form of book prints mainly depends on the intention and taste of the book engraver, as well as the function of the printed copy. Geographically, "Mulian Rescue Mother", which belongs to Huizhou, is far from the style and taste of Huancuitang, but it is closer to the three printed editions of Yongshun Shutang, Fuchuntang, and Qiaoshantang. orientation and positioning. This is also the reason why "rough" and "majestic" prints exist in all book engraving areas, not limited to Nanjing. For this type of print, it may be more appropriate to call it "folk style".

Fig. 8 "New engraving and re-editing of phases with annotations and notes on Yueting Ji"

Figure 9 "Revisiting Yuanben Big Board Interpretation Holographic Audio Interpretation of Pipa", Wanli Shidetang Publication

In fact, the Fuchuntang style only represents a certain type of reading orientation in Nanjing’s diversified market. Considering the cost of engraving books and readers’ tastes, various bookstores in Nanjing, including the same bookstore, have different choices in different periods. same. "Jingtai Xinqigong Yu Shenglan National Beauty and Heavenly Fragrance" published by Zhou Yuexiao Wanjuanlou, both in text and illustrations, has strong Jianyang characteristics. In the 17th year of Wanli (1589) Shidetang published "Newly Engraved and Re-edited with Notes and Notes on Yueting Ji" (Figure 8) is still a typical Fuchuntang schema, and another engraved edition "Re-adjusted Yuanben Daban However, the illustrations of the Interpretation Hologram Yinshi Pipa Ji are very different, showing obvious signs of imitating Huizhou style (Figure 9). Other bookstores, such as Chen Dalai's Jizhizhai, Tang Jinchi's Wenlin Pavilion, and Tang Zhenwu's Guangqingtang, all turned to Wang Geng's meticulous painting style. The popularity of Huizhou style in the Nanjing book market is closely related to the strong aesthetic atmosphere of scholars in this area. In the evaluation system of literati paintings, the description of characters has corresponding value standards. Just as the rapid and sharp line outlines of the late "Zhejiang School" were considered "unrefined", the Wumen painting style of leisurely, subtle and subtle brushwork is authentic. In the eyes of modern scholars, the Fuchuntang-style boldness may have a lively and simple atmosphere, but in the atmosphere of literati painting in the south of the Yangtze River, compared with the finely carved Huizhou printed version, the result is self-evident. figurative.

Figure 10 "Tang Poems and Paintings" Wanli Collection Yazhai Block Edition

However, the era of Huizhou style is coming to an end. From about the late Wanli period, imitating the painting style of the Wu School, emphasizing artistic conception and literariness gradually replaced Wang Geng's style of laying out, and became the mainstream of high-end prints. The change in book engraving style is more evident in the publication of Appreciation Atlas. The popular "Gu's Painting Book" and "Tang Poetry Painting Book" paid more attention to leisurely literati and artistic poetic sentiments (Fig. 10), and there were also many "showing elegance" with Cheng Junfang, Fang Yulu and others for the purpose of making ink and propaganda same. The prevalence of Huizhou style is due to its dense layout and modular "components", while literati paintings focus on the authenticity and unrepeatability of inner experience, just like the aura in the art works described by Walter Benjamin. ):

The strange entanglement of time and space: the singular manifestation of something far away, as if it were near at hand. Resting at noon in summer, following the arc of the mountain on the horizon, or following a branch of a tree projected on the viewer, until "this moment" becomes part of the image—this is breathing the mountain , The aura of the branch.

The "here and now" emphasized by Benjamin refers to the unique presence of aesthetic and creative experience. For the public in the era of woodblock print reproduction, it is easier to obtain the uniqueness of things through the printed matter of images. From the perspective of a literati reader in the late Ming Dynasty, "Gu's Painting Book" and "Tang Poetry and Painting Book" provided a possibility of private repeated browsing experience. The viewing activities and the influence of previous owners have become the "spiritual friendship" with the image at the moment. During the Tianqi and Chongzhen periods, the advent of color overprint prints by Wu Faxiang, Hu Zhengyan, Min Qiji, etc., satisfied the intellectual readers' constant pursuit of sensory enjoyment and elegant sentiment, and also made the products of Wang Yunpeng and Wang Tingna increasingly appear "low end".

The Huizhou style gradually disappeared around the middle of the 17th century, and what became popular in the book market was a graphic style that was closer to the style of literati painting and more sophisticated and diverse in terms of "rhetoric". Behind the gorgeous pictures of Huizhou style, there is a kind of expression of perfection and exquisite taste. This deliberate, "for fear that people don't know" construction method is almost a behavioral code exclusive to Huizhou businessmen, which is completely opposite to the implicit and self-admired style advocated by the scholar class. In the Jiangnan area where the literati atmosphere is strong, readers' appreciation tastes fully reflect the trend of following the aesthetic standards of scholars. With the continuous changes in the standards of the publishing market, printed books and prints are also transformed into forms that are more adaptable to new changes.

(The author of this article is the Chinese National Academy of Arts. The original title of the article is "Huizhou Style: The Evolution of Book Prints from the 16th to the 17th Century". The full text was originally published in the 12th issue of "Art" magazine in 2022.)