Sealing clay is a derivative that accompanied the early seals. As a relic of 2,000 years ago, sealing clay was rediscovered and studied only two hundred years ago, but it was nearly thirty years ago that it was actually displayed in the museum as an exhibit. thing.

The 15-volume "Complete Collection of Ancient Chinese Sealing Clay", which was collected and compiled by the editorial team led by Sun Weizu, a research librarian at the Shanghai Museum, was published recently. This book is by far the most abundant material, the most comprehensive system, the longest historical span, and the most three-dimensional academic information. This article is an excerpt from a paper written by Sun Weizu for "Complete Works", which systematically discusses the discovery and unearthed conditions of the sealing mud.

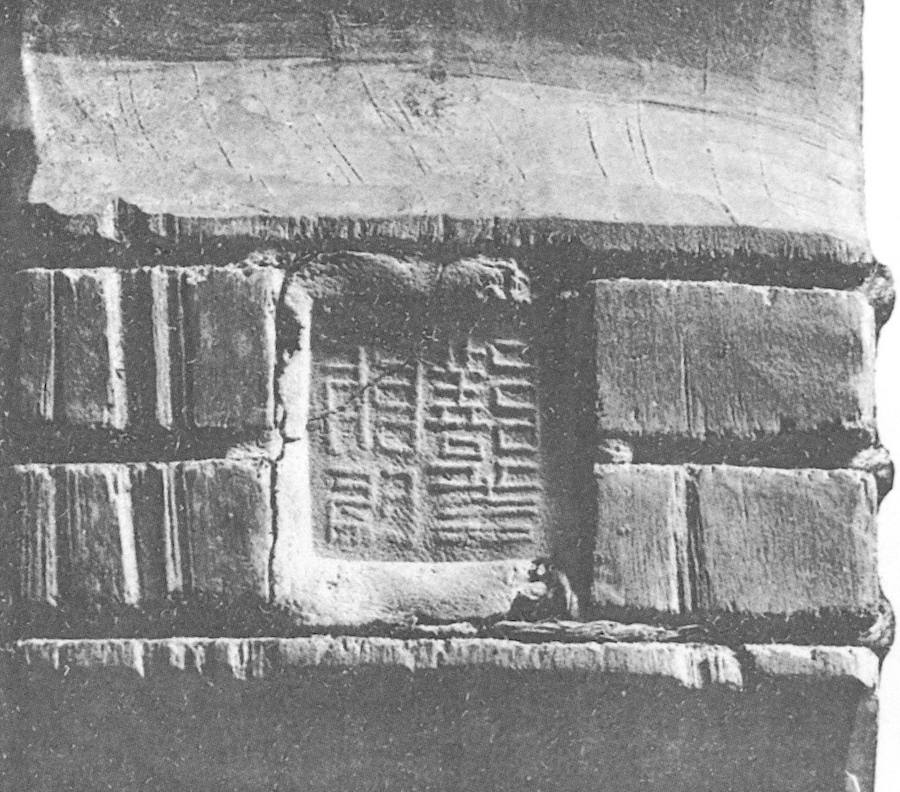

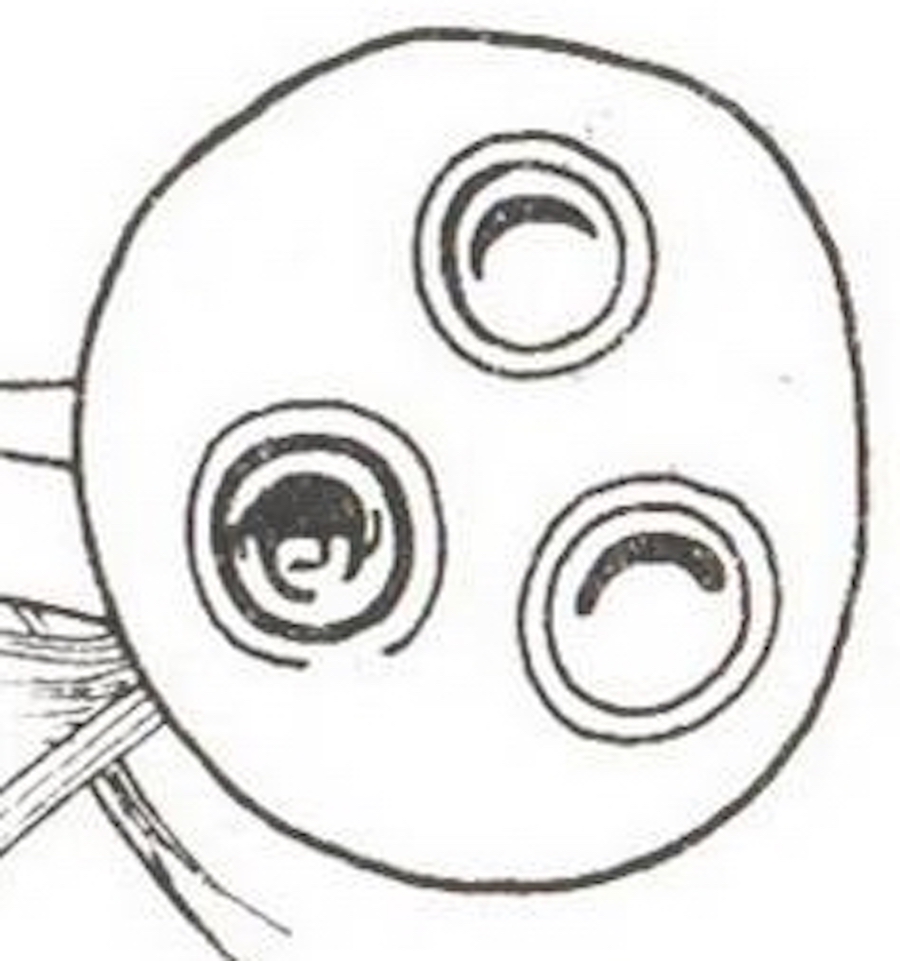

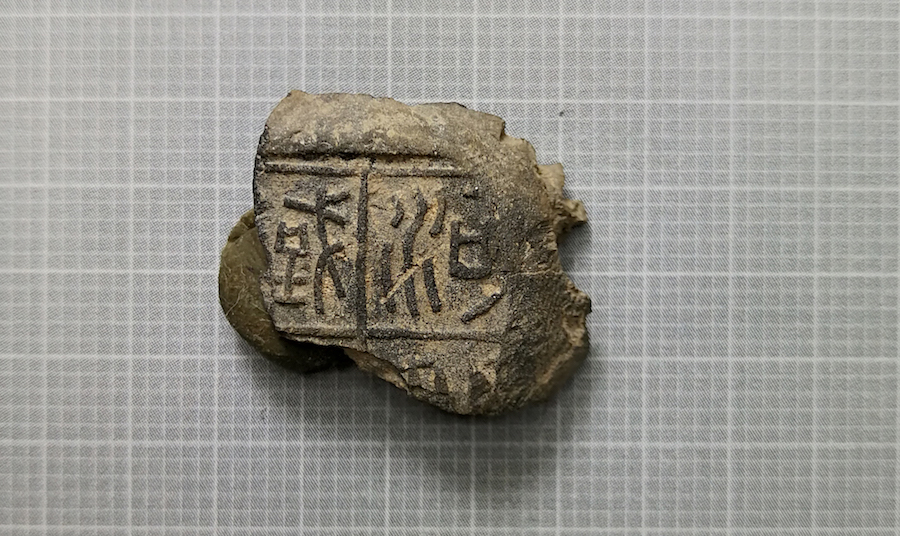

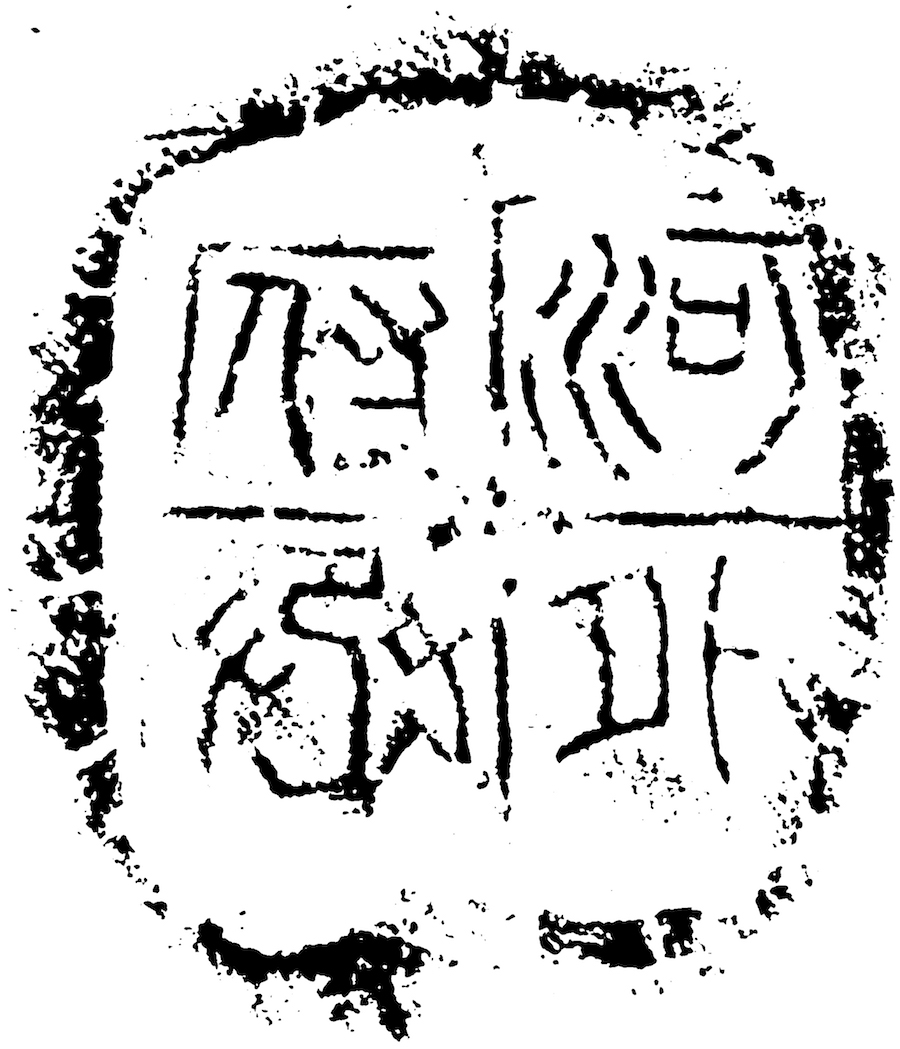

The use of several original seal systems in the world shows that the sealing clay is a derivative that accompanied the early seals. This feature is evidenced by the mud balls with patterns found in the Alpakia site in northern Mesopotamia (Figure 1) and the mud seals left by the first dynasty of ancient Egypt (Figure 2). The name "Feng Ni" appeared in ancient Chinese historical records, and it can be found in "Hou Han Shu · Baiguan Zhi" Shaofu "There is a man who guards the palace order". . Judging from the discovered objects, its existence in ancient Chinese social life began more than 2,000 years ago; if inferred from the literature records, its appearance should be earlier.

Judging from the social use of seals, China's Warring States Period to Wei and Jin Dynasties were in the era when seals were commonly used. The basic function of seals in this era, as a proof, is to seal on the clay, so as to realize the various meanings set by society. After the Southern and Northern Dynasties, it continued to exist in different forms in certain areas of social life, which is its remnants, and it has been completely separated from the general system of seals and seals.

The characteristic of Chinese seals is that words are used as the main form of expression. After the formation of a centralized state, the official seals from the central government to the local grassroots level have strict institutional norms, which are closely related to the bureaucratic system and administrative activities. Therefore, the seals and their mud seals carry various historical information. Due to the favor of historical conditions, ancient Chinese sealing clay, especially official seal sealing clay, has been preserved in large quantities by accident, and its rich text content is unprecedented in other areas where early seals originated in the world. The ancient Chinese sealing clay became the research object of late Qing epigraphy and contemporary philology, historical materials and seal studies.

Figure 1 Mud mass unearthed from the Alpacia site

Figure 2 Relics of the First Dynasty of Ancient Egypt

1. Discoveries from late Qing Dynasty to modern times

Sealing clay, oracle bones, and bamboo slips are all relics of ancient writing that have been rediscovered in modern times. Compared with seal seals, sealing mud was discovered and used as a research object about a thousand years later. From the late Qing Dynasty to the Republic of China, the excavation and collection of sealing clay can be roughly divided into two stages.

The first stage: from the early years of Daoguang to the last years of Tongzhi—Central Shu and Guanzhong

The earliest to come into the sight of the Jinshi family is the so-called sealing mud unearthed in Shu and Guanzhong. Wu Rongguang copied six pieces of clay seals including "Gangli Youwei" in "Junqingguan Jinshi", and said in the preface of the book that the clay seals were obtained from "Shu people digging yam" in the second year of Daoguang, and recorded the number as " More than a hundred pieces". According to the official titles and place names contained in the mud seals of this system, we can speculate that the place where the "Shu people" discovered the mud seals at that time should be a county site in the Han Dynasty, but there were no new discovery clues in the Shu area.

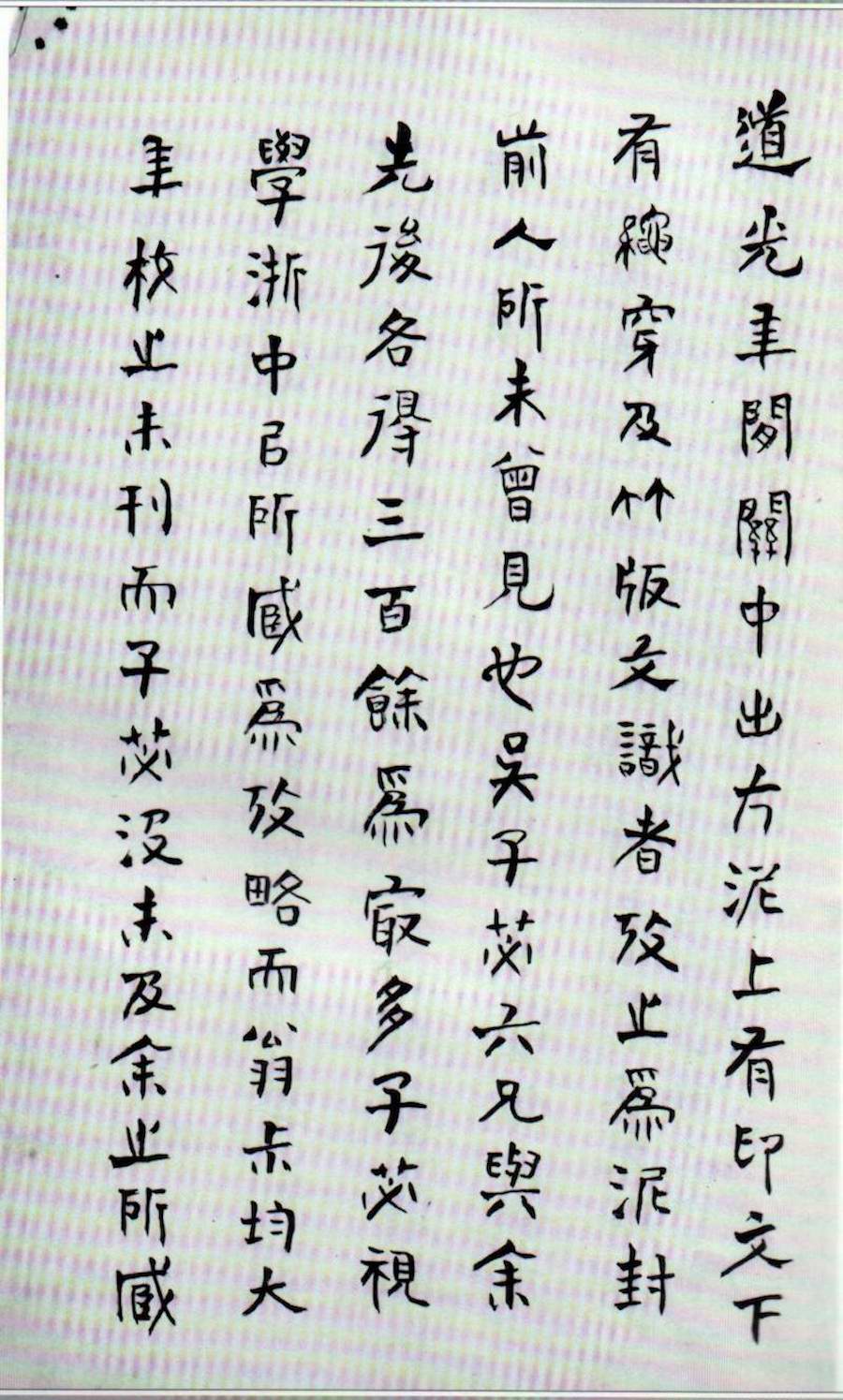

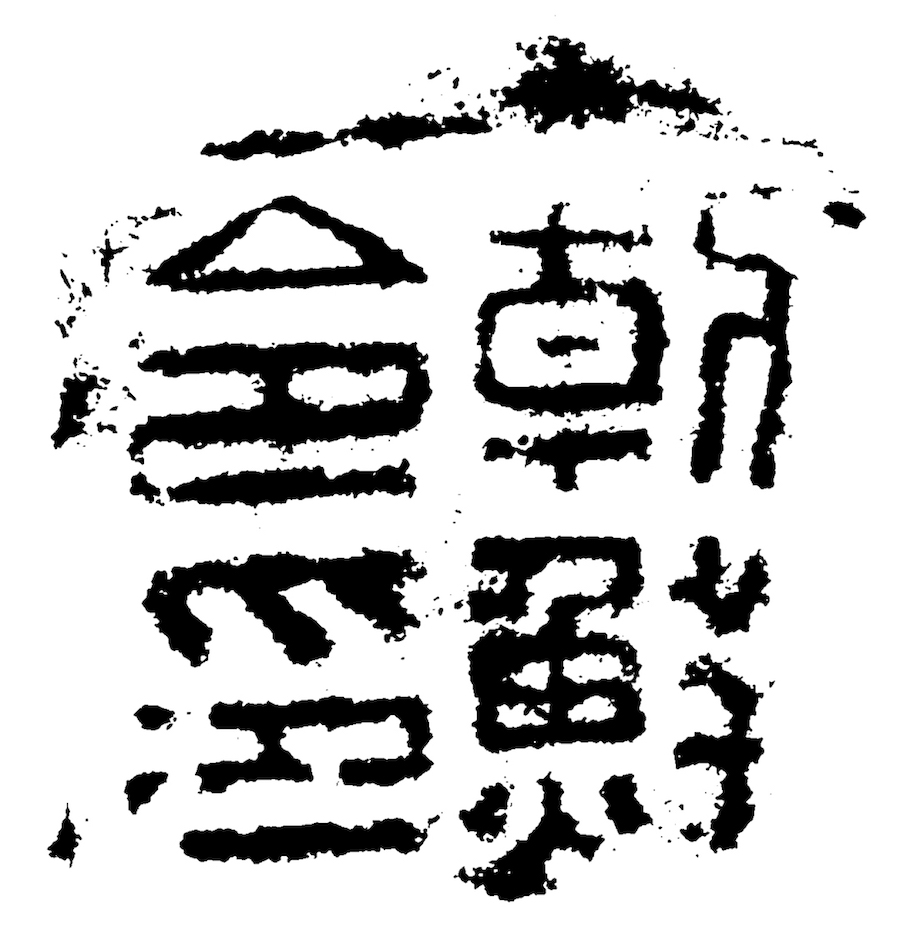

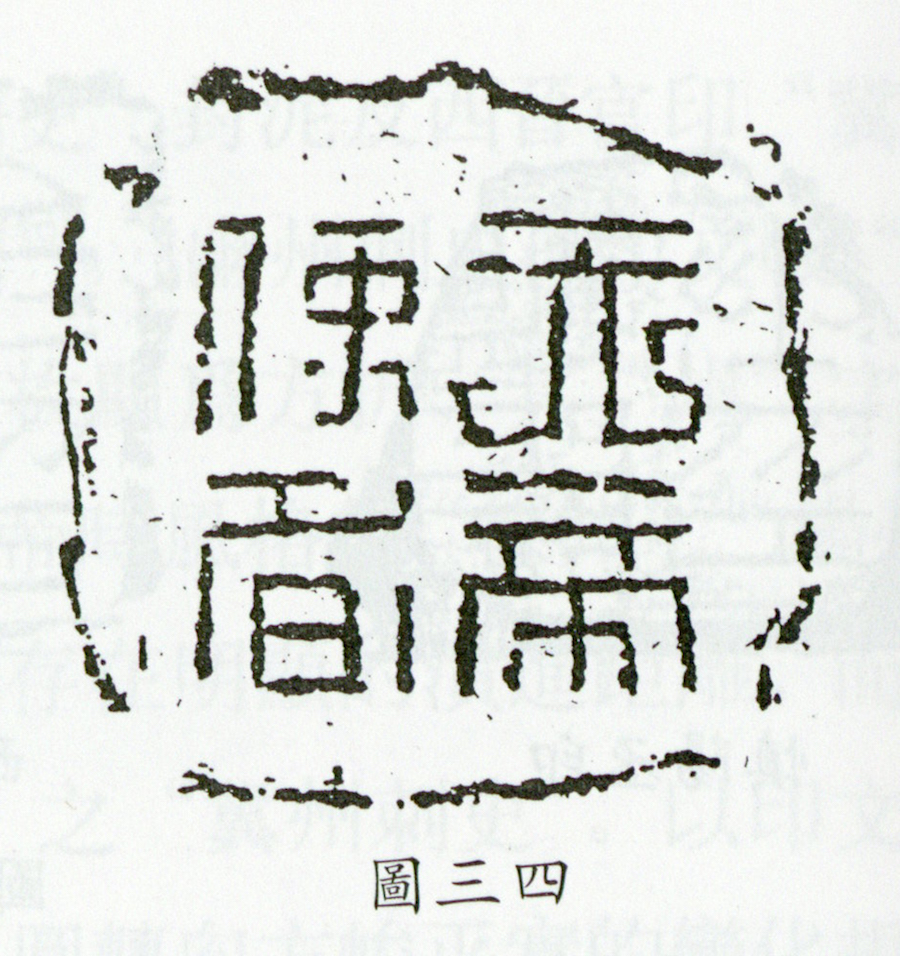

Fig. 3 Inscription on Chen Jieqi's Notes on "A Brief Study on the Clay Seals of Han Officials' Private Seals"

Fig. 3 Inscription on Chen Jieqi's Notes on "A Brief Study on the Clay Seals of Han Officials' Private Seals"

The record of the discovery of mud seals in Shaanxi can be found in the manuscript of Chen Jieqi in "A Study of the Private Seals of Han Officials": "The square mud came out of the Guanzhong between Daoguang and Guangjian. Wu Zibi's six brothers and I each got 300 pieces, which is the most." (Figure 3) In the second year of Xianfeng (1852), more than 30 clay seals included in Liu Yanting's "Chang'an Huo Gu Bian" also came from Xi'an.

The sealing clay obtained by Liu Yanting was transferred to Chen Jieqi around the Tongzhi period. Wu Shifen and Chen Jieqi obtained more than 1,000 pieces of sealing clay since then.

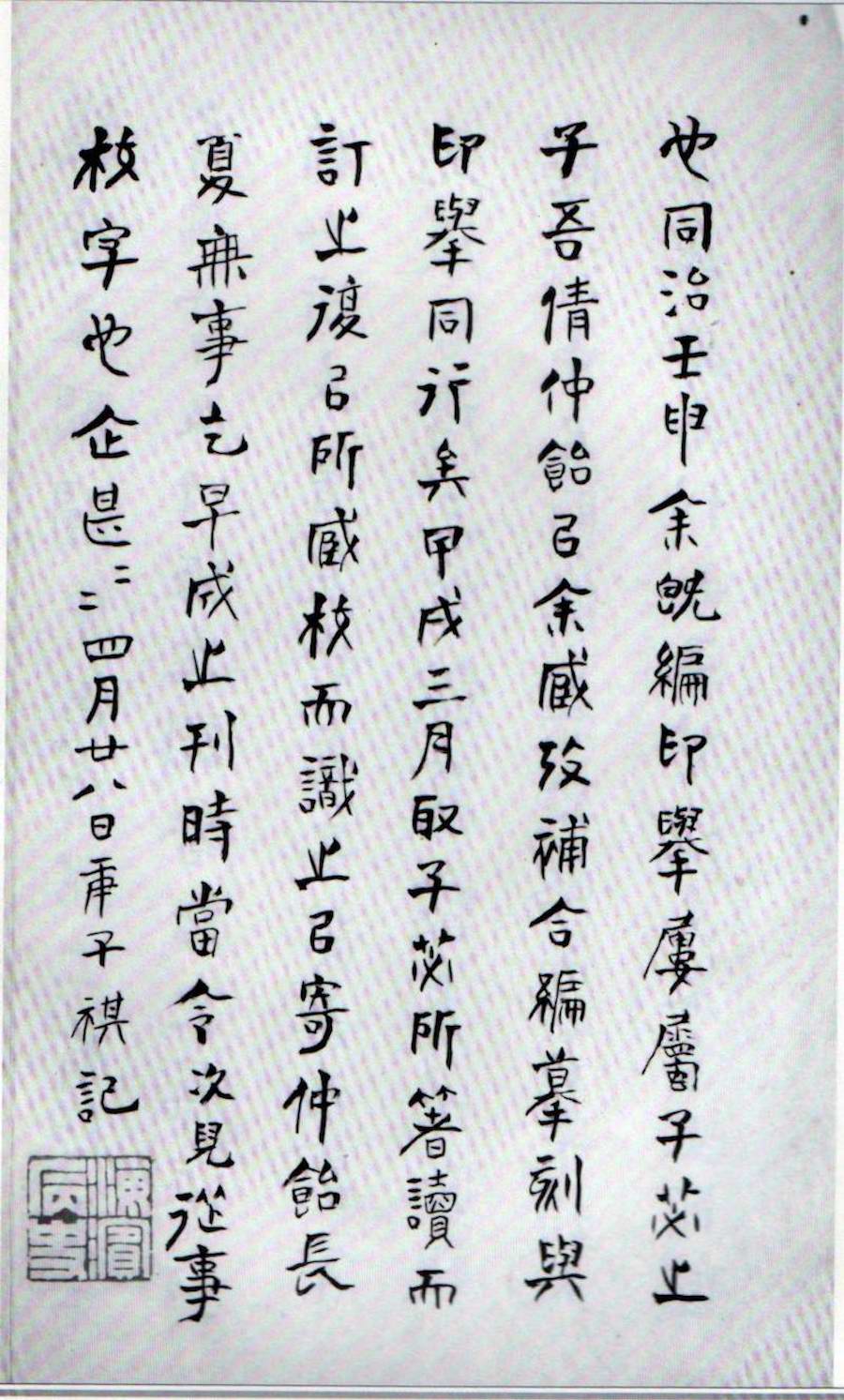

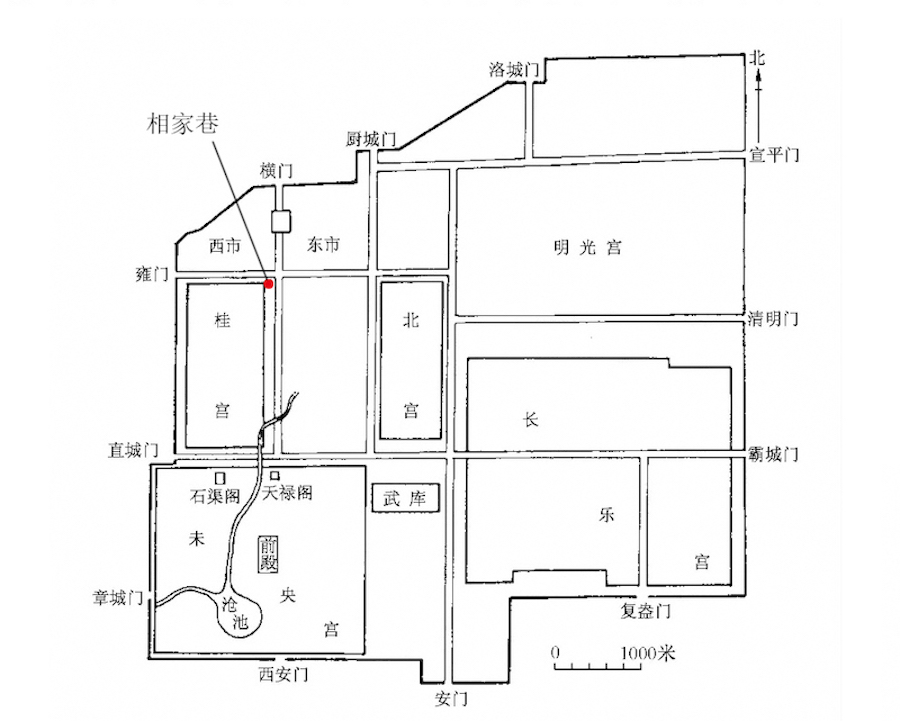

This part of the engravings contains official titles such as Zi, Nan, and Fucheng from a wide range of Western Han county guards, county lieutenants, Wang Guoxiang, and Wang Mang. In addition, there is also a part of Qin official sealing clay in Wu and Chen sealing clay, and its category is the same as that produced in Xi'an Xiangjiaxiang later. The main part is from the late Western Han Dynasty and the middle and late Western Han Dynasty. This connotation suggests that the above-mentioned sealing clay should come from a central government office or palace site from Qin, Western Han to Xinmang somewhere in Xi'an. According to my research on the types and forms of Wu Shifen and Chen Jieqi's clay seals collected by Shanghai Museum and Tokyo National Museum, the ones from Guanzhong should be the main part.

At this stage, the information about the location and scope of the excavation of the sealing mud is vague, and the specific locations of Shu and Guanzhong are unknown, which is related to the social awareness of the sealing mud at that time.

The second stage: from the early years of Guangxu to the period of the Republic of China—with Qilu as the center

Figure 4 Schematic diagram of the location of the ancient city of Qi (taken from the "Brief Excavation of the Old City of Qi in Linzi, Shandong")

In this stage, apart from sporadic discoveries in other unknown locations, the bulk of the unearthed was in Linzi District, Shandong Province, so the types and times of clay seal characters were also different from the previous stage. In the second year of Guangxu (1876), Chen Jieqi was awarded the seal of "Gumu Chengyin". In his letter to Wu Dacheng, he mentioned: "There is actually a clay seal in the eastern land". The clay seals produced in the early days were obtained by Chen Jieqi, Wu Shifen, Liu E and others. In the 23rd year of the reign of Emperor Guangxu, more than 100 pieces of sealing clay were unearthed from the farmland near Liujiazhai in the north of Linzi City. According to Wang Xiantang's "Linzi Sealing Clay Text Syllabus" (hereinafter referred to as "Linzi Syllabus"), there were two large and small cities in Qi, and the small one was Miyagi. , Great for the national government and the county government, the seal of the mud came out, in Linzi "the central and southern area of the big city, the Shouxiang County Magistrate's Office was once set up as a room". (Fig. 4) The place where the excavation was unearthed, "all regions are connected into one area, about 20 mu, and the soil is three feet, and it can be obtained. There are dozens or hundreds of cellars, and as few as three or four pieces." Therefore, he believes that " At that time, the site was almost the former site of the government office, which was left behind by the burning of documents and documents.” This is the earliest record about the specific place where the mud was found. The seal clay from Liujiazhai was collected successively by descendants of Chen Jieqi, Guo Yuzhi, Gao Hongcai, Wang Yirong, Ding Shuzhen, Sun Wenlan, Chen Baochen, Zhou Jin, Luo Zhenyu and other families. Some of them were later transferred to the Shandong Provincial Library, and Wang Xiantang was in charge of it. In 1936, it was expanded into "Linzi Sealed Clay Characters" (hereinafter referred to as "Linzi"), and the total number of catalogs reached 464. About a little earlier than this year, Peking University collected 170 clay seals acquired by Guo Yuzhi. This is the beginning of large-scale collection and research of sealing mud by domestic public institutions. After the middle of the 20th century, most of the sealing clay collected by Zhou Jin, which was acquired by the Shanghai Museum, also came from Linzi. According to the author's statistics, the total number of clay seals unearthed in Shandong during this period is about 1,500 or more. The era includes the Warring States Period, Qin Dynasty, and Han Dynasty, and the early Western Han Dynasty is the most common. Some collectors of gold and stones in Shanzuo competed to collect them, and the trend of textual research and description became more and more popular.

During this period, foreign archaeologists discovered the mud seals outside the inner county, which became unearthed records in the archaeological sense.

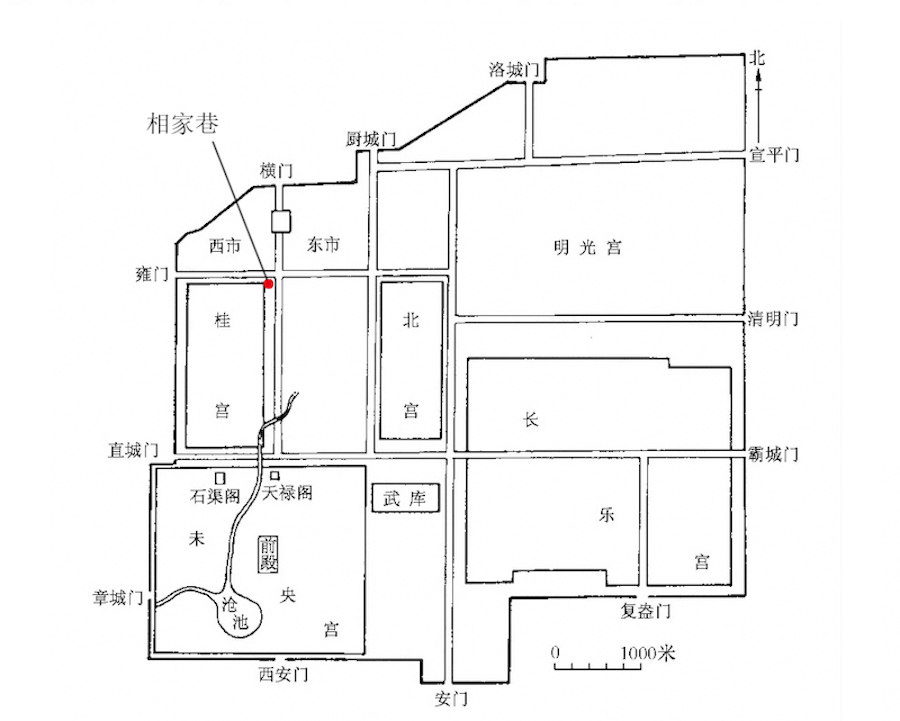

Figure 5 Graphic seals on wooden tablets in the Khalu language unearthed from the Niya site (taken from "Illustrated Records of Archeology of the Western Regions")

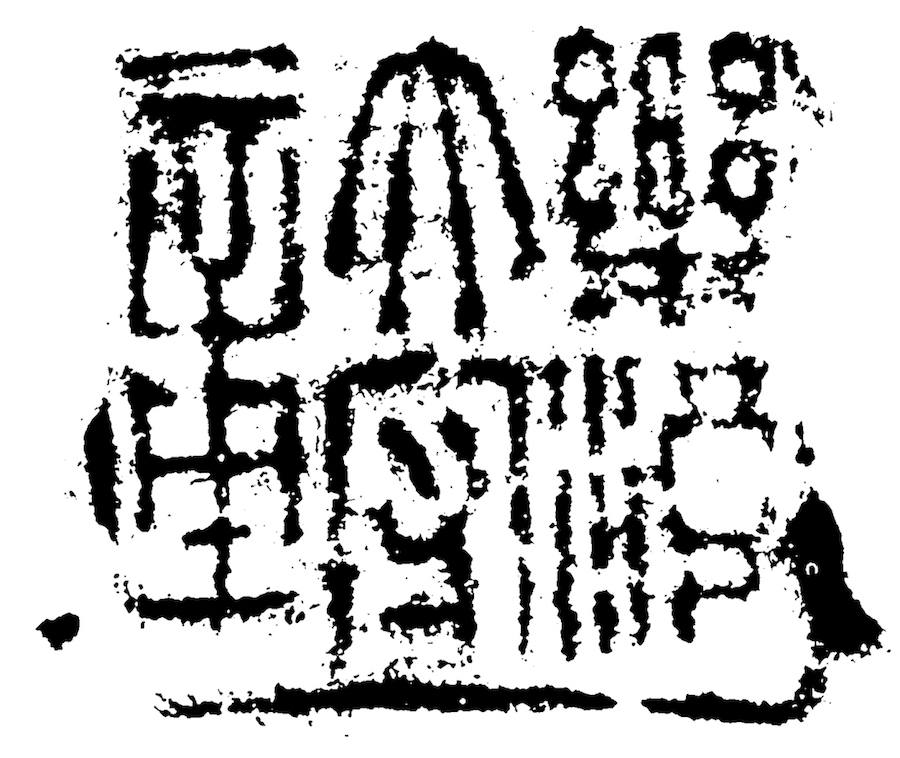

After 1901, Stein discovered a batch of wooden tablets in Chinese and Lu script at the Niya site in Xinjiang, accompanied by clay seals with images of ancient countries in the Western Regions (Fig. 5) and clay seals with Chinese characters "Shanshan Junwei" (Fig. 6) still preserved on the broad slips among. From the pictures collected in this edition, we can see that these clay seals are different from the ones from the aforementioned places, but the shape of the wooden tablet seals still follows the elements of the Three Kingdoms era in Neijun and has changed. The dissemination of "Shanshan Junwei" and the existence of "Shanshan Junwei" and its seal style, the era of sealing mud should be around the fourth century AD.

Figure 6 Shanshan County Lieutenant (taken from "Illustrations of Archeology in the Western Regions")

Figure 7 Schematic diagram of the unearthed sites of the Lelang County site in Han

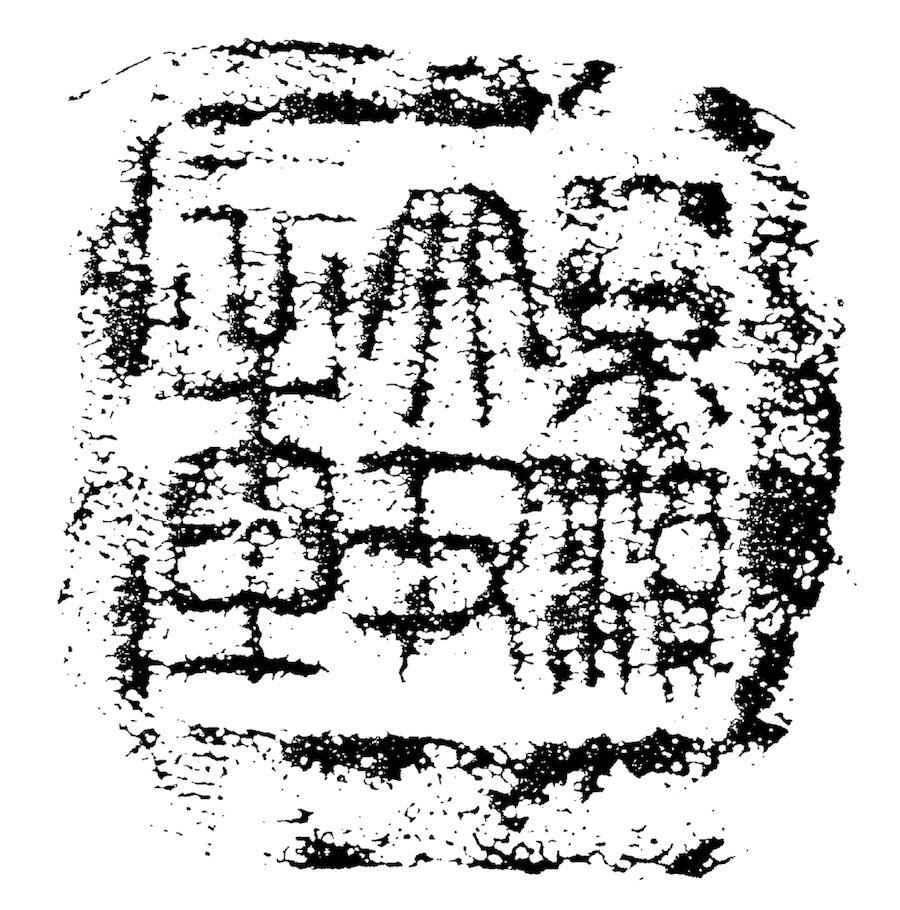

It was around the 1920s that the ruins of Hanlelang County in Tucheng, Tucheng, on the south bank of the Datong River in North Korea (Figure 7) were unearthed successively. In 1935, the Korean Antiquities Research Association conducted two excavations and surveys to confirm the discovery area and excavation status of the mud seal. Most of the mud seals unearthed from the excavation (including collection) of the Lelang site have been recorded in detail by Fujita Ryosaku, and the place names and official systems have been researched and interpreted, totaling more than 200 pieces. Among them, such as "Korean Order Seal" (Fig. 8), "Le Lang Prefect Chapter" (Fig. 9), "Le Lang Dayin Chapter" (Fig. 10) and other era attributes are clear. The excavated mud seals unearthed by Le Lang compiled by this editor include the excavated items collected by the Archaeological Research Office of the University of Tokyo (formerly Imperial University), part of the collection of the National Museum of Korea (formerly the Museum of the Governor-General of Korea) and the entire collection of the Tokyo National Museum.

Figure 8 North Korea's order and seal

Figure 9 Le Lang prefect chapter

Figure 9 Le Lang prefect chapter

Figure 9 Le Lang prefect chapter

Figure 10 Le Lang Dayin Zhang

Before the founding of the People's Republic of China, there were more than 3,000 recorded clay seals. This part of seal clay handed down from generation to generation was mainly collected by several epigraphers in the late Qing Dynasty, and was later collected by Shanghai Museum, Tokyo National Museum, Shandong Provincial Museum, Peking University, Jinan City Museum, Otani University in Japan, and National Museum of Korea. Other institutions and individuals at home and abroad also have varying numbers of collections.

Before the 1950s, the unearthed bulk of recorded mud seals showed relatively concentrated accumulation and burial, which should be a relatively fixed disposal site within a period of time after unsealing and inspection. This state was found continuously later. The author calls it the phenomenon of "sealing mud groups". Noticing this, based on the categories and textual connotations of official seals unearthed in a centralized manner, it is meaningful for archaeological research to determine the status of administrative activities and their ascending and descending relations in a certain period of time, which will help to infer the location of the excavation or the nature of the site. of.

2. Unearthed in the age of archaeology

Since the 1950s, it has entered the stage of archaeological discovery of ancient clay seals. The sealing mud unearthed from the tomb has become a new record, which has promoted the expansion and deepening of the research field of sealing mud.

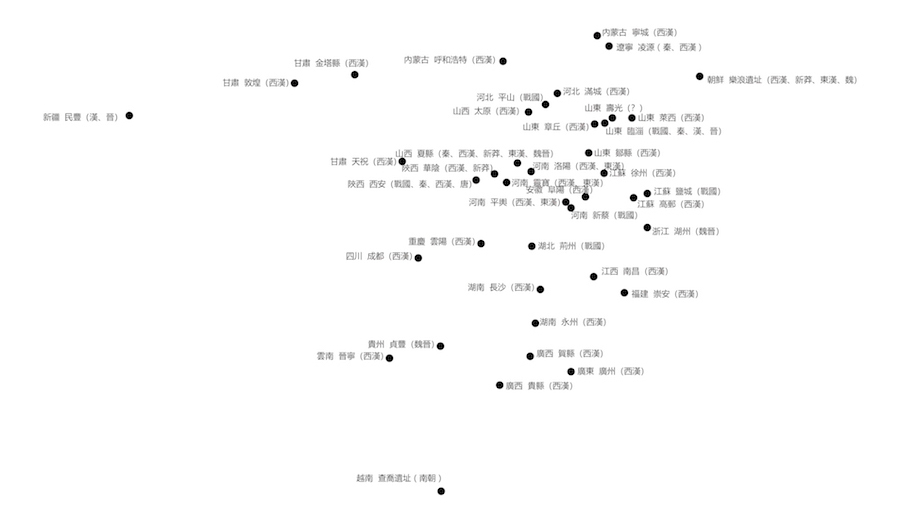

Figure 11 Schematic diagram of the excavation site of sealed mud in China

Since the founding of the People's Republic of China, the clay seals discovered by archaeology are mainly from tombs, and some are from the excavation and cleaning of the ruins. The total number of them has reached more than 700. City, Dingzhou, Cangzhou), Shanxi (Taiyuan, Yanggao), Inner Mongolia (Hohhot, Ningcheng, Ejina), Liaoning (Lingyuan, Fushun, Jinxi, Chaoyang), Jiangsu (Gaoyou, Xuzhou, Yangzhou, Suzhou, Yancheng , Xuyi), Zhejiang (Huzhou), Anhui (Fuyang, Fengyang, Lu'an, Bengbu), Fujian (Chong'an), Jiangxi (Nanchang), Shandong (Jinan, Laixi, Changle, Zhangqiu, Linzi, Juye , Qingzhou), Henan (Luoyang, Lingbao, Xinxiang, Yongcheng), Hubei (Yunmeng, Jiangling, Baoshan, Yichang, Yunxian), Hunan (Changsha, Yongzhou, Liye, Yuanling), Guangdong (Guangzhou, Wuhua), Guangxi (He County, Gui County), Chongqing (Yunyang), Sichuan (Chengdu), Yunnan (Jinning), Shaanxi (Xi'an, Xianyang), Gansu (Juyan, Dingxi, Dunhuang, Tianzhu), Xinjiang (Minfeng, Niya), Ningxia (Yanchi) and other places; North Korea (Lelang site) was discovered in the early stage abroad, and Vietnam (Chaqiao Goose Brocade site) and Mongolia (Bayanbulag fortress site) were discovered in recent years. The age of these mud seals is relatively clear, and the research information is rich, and the information has been published in various archaeological and cultural relic research journals. Among them, the most unearthed ones are:

From April to June 1955, the Henan excavation team of the Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Sciences excavated more than 20 pieces of mud such as the "Henan Taishou Chapter" in the ash pit of the Han Dynasty site in the western suburbs of Luoyang.

In October 1958, during the investigation and excavation of the ancient city of Qi in Linzi, Shandong, more than 40 pieces of mud seals such as the "Qi Nei Official Seal" were unearthed in Liujiazhai to explore the Han Dynasty layer. The connotation of the printed text is the same as that published earlier.

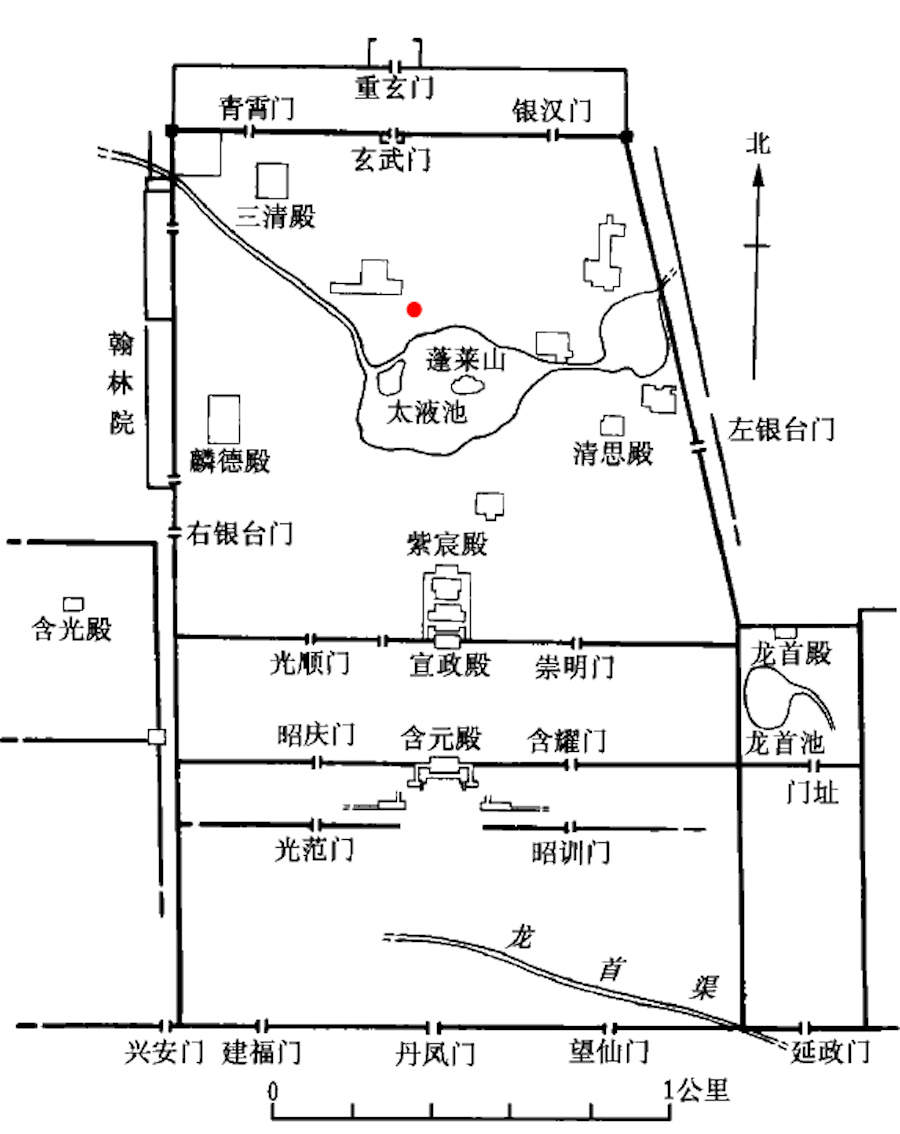

From March 1957 to May 1959, more than 160 pieces of clay seals from the Tang Dynasty, including the "Tanzhou Dudufu Seal" were unearthed from the Tang Chang'an Daming Palace site.

In 1972, 37 pieces of mud seals such as "Jihou Jiacheng" and "Youwei" were unearthed from Han Tomb No. 1 in Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan, and a "mud seal box" was unearthed at the same time. Tomb No. 3 also yielded the "Yuan Jiacheng" and a piece of "incomplete" sealing clay (Fig. 12). The latter was reconstructed and interpreted as "Li 狶", and at the same time, two different "Jihou Jiacheng" were found through analysis (Figure 13).

Figure 12 Leap

Fig. 13 Jiacheng of the Marquis Hou (collected by Hunan Provincial Museum)

Fig. 13 Jiacheng of the Marquis Hou (collected by Hunan Provincial Museum)

In 1977, 22 pieces of mud seals such as "Chu Nei Guan Cheng" were discovered and collected during the investigation of the Han Dynasty tombs in Tushan, Xuzhou.

In 1983, 35 clay seals such as "Emperor Seal" and "Zhen" were unearthed from the tomb of Nanyue King in Xianggang, Guangzhou.

In 1987, 85 pieces of mud seals from the "Suichuan Houfu" were unearthed from the Western Han Tomb in Dongquan Village, Changle County, Shandong Province.

From October 1987 to May 1988, 112 pieces of mud seals such as "Zhang Mu Da Fu Zhang" and "Chen Zun" were excavated and cleared from the architectural site of Weiyang Palace No. 4 in Xi'an. The mud seals are all left over from the seal inspection in Wang Mang's era.

In the archaeological excavations after 1990, there are several more important discoveries:

The mud group of the tomb of the king of Chu in Lion Mountain, Xuzhou. From December 1994 to March 1995, more than 80 pieces of sealing clay such as "Fu Licheng Seal" were unearthed from the tombs of the Han and Chu kings in Shizishan. Published many papers such as Wang Kai's "The Significance of Seals and Seals Unearthed from the Mausoleum of the King of Chu on the Lion Mountain to the Study of the Establishment and Territory of the Chu State in the Western Han Dynasty" and Zhao Ping'an "Re-understanding of the Seals and Seals Unearthed from the Lion Mountain", discussing the The age of seals and mud seals from the tomb, and the feudal domain of Chu State in the early Western Han Dynasty. Since the age of the Chu King's Mausoleum in Shizishan is relatively clear, it is the same as the Mawangdui Han Tomb and the Nanyue King's Tomb, and it is also the standard for the writing and shape of the clay seals in the early Western Han Dynasty.

Xi'an Yangling and Yanglingyi Fengni Group. From 1998 to 2008, more than 1,100 pieces of Hanfeng clay were excavated by the Shaanxi Hanyangling Mausoleum archaeological team. Among them, the unearthed official seal clay preserved several official names that were unknown before. Yang Wuzhan analyzed the age and form of the unearthed mud seals in the article "Examination of the Excavated Seals from the Hanyang Mausoleum". The mud seals unearthed including the Yangling Waizang Pit, the "Luo Jingshi" site, the Eastern District Burial Pit, and the Yanglingyi Ruins can be regarded as a group of related mud seals. For the early Western Han Dynasty, it has the significance of dating specimens. The age of sealing mud in Yanglingyi lasted for a long time, reaching the Xinmang period.

The sealing mud excavated from Mawangdui Han Tomb, Nanyue King Tomb, Shizishan Chu King's Mausoleum, Yangling Waizang Pit, and accompanying burial pits has not been burned, and some of them have preserved seals, which are different in nature from those from the site. In addition to supporting the identity of the tomb owner, it also has specimen value in reflecting the burial customs of the Han Dynasty and the original sealed form of the burial objects.

Xuzhou Tushan Fengni Group. Since 1994, more than 4,500 pieces of Han Dynasty seals have been successively removed from the seals of Han tombs in Tushan (Fig. 14) by Xuzhou Museum. At present, the cleaning work is still in progress, and some information has been published. The sealing mud from Tushan is quite special. As far as the author sees, the main part is the remains of the early Western Han Dynasty, and the era of a small amount of mud sealing extends to Xinmang. According to the written content of the sealing mud, it can be determined that the sealing mud and the sealing soil came from a certain official site from Chu State in the early Han Dynasty to Xinmang, and the place should not be too far from Tushan. The sealing mud obtained by Tushan is not only a considerable amount, but also involves many categories. Li Yinde's "Overview of Seals and Seals of the Western Han Dynasty Unearthed in Xuzhou" reports some results of research on seals, seals and mud seals unearthed in Shizi Mountain in recent years, and puts forward new conclusions about the nature of seals unearthed in Shizi Mountain and the age of mud seals in Tushan Mountain. Lü Jian/Du Yihua's "Analysis of the Original Deposition Site and Properties of the Sealing Mud Unearthed from Tushan Han Tombs" made an in-depth discussion on the seal, age and nature of some of the sealing mud, revealing its significance for the study of the territory of Chu State in the Western Han Dynasty. In the Western Han Dynasty, there were few seals found in Chu State in the past. According to Li Yinde’s disclosure, most of the earthen seals were found in Chu State and its county officials in the early Western Han Dynasty. The research on the official system of the vassal kingdom and the feudal domain of Chu State will bring new discussions space.

Figure 14 Sun Weizu inspected the fief landform at the tomb of King Pengcheng of the Han Dynasty in Tushan (photographed in 2004)

Qinfeng mud group in Xiangjia Lane, Xi'an. From April to May 2000, the Hanchangan City Archaeological Team of the Institute of Archeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences excavated and cleared Xiangjiaxiang Village, Liucunbao Township, Weiyang District, Xi’an (Figure 15), and confirmed that the site was from the late Warring States period to the Qin Dynasty. 325 pieces of clay seals were unearthed from the architectural site. Prior to this, from the end of 1996 to the beginning of 1997, the Xi'an Institute of Cultural Relics Protection and Archaeology carried out rescue excavations in this area, unearthed more than 10,000 pieces of mud seals. Information has not yet been published.

The location map of Xiangjia Lane (taken from "Green Clay Treasures - Proceedings of the International Symposium on Sealed Clay Inscriptions in the Warring States Period, Qin and Han Dynasties")

A large number of mud seals were unearthed in this area earlier, most of which were collected by individuals. The Xi'an Chinese Calligraphy Art Museum has collected some seals with relatively complete shapes. In addition, after the discovery of mud seals in Xiangjiaxiang Village, it is rumored that some mud seals were also found in the neighboring Liucunbao Township and Gaoling District of Xi’an. (hereinafter referred to as "Compilation"), according to the sealing clay compiled, some of the seal styles passed down from Gaoling are earlier than those from Xiangjiaxiang.

According to the preliminary understanding of many cultural relics and archaeological institutions and personal collections, more than 20,000 pieces of sealing mud (including fragments) have been successively released from the ruins in this area. This batch of clay inscriptions on Qin seals contains unprecedentedly rich official and administrative geography historical materials, which brought an opportunity to advance the research field of Qin history in the 20th century.

In the archaeological work since the 21st century, there are still several unearthed records with a large number of mud seals, such as:

In 2009, more than 20 pieces of mud seals from the "History of General Wei" were unearthed from the Fengqiyuan Han Tomb in Xi'an, Shaanxi.

In 2010, a total of 82 pieces of basically complete and damaged sealing clay with seals and ink writings (Figure 17) were unearthed from the northern ash pit of Taiye Pond (Figure 16) in the Daming Palace in Chang'an, Tang Dynasty. This batch of sealing clay is of the same nature as those produced at the Daming Palace site from 1957 to 1959, and it is the symbol of the sealed jars left on the porcelain jars that sent tributes from various states in the Tang Dynasty. In recent years, it has been reported that the remains of the Northern Song Dynasty imprinted mud on containers from the site of Liaoqingzhou City, Balin Right Banner, Inner Mongolia, indicate that this use method has continued.

Figure 16 Schematic diagram of the mud sealing site unearthed from the northern ash pit of Daming Palace Taiye Pool in Chang’an, Tang Dynasty (provided by Gong Guoqiang)

Figure 17 Seal of Cangzhou (Provided by the Xi'an Tangcheng Task Force of the Institute of Archeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences)

In 2011, more than 50 pieces including the "Dingmao Cheng Seal" and "Dingmao Seal" were unearthed at the Shixiongshan Site in Wuhua, Guangzhou.

In 2011, more than 40 clay seals were discovered at the site of Guyang City, Guzhen County, Bengbu, Anhui Province, and most of them with clear handwriting were private seals.

The mud seals obtained by archaeological excavations in recent decades extend from the middle of the Warring States Period to the Tang Dynasty, but the main body is still in the Qin and Western Han Dynasties. The number from the tombs is mostly only one to a few pieces, and those with more than 20 pieces basically belong to the tombs of princes; the number from the ruins is relatively large. This part of the sealing mud not only has outstanding historical significance, but also provides a reliable standard for the study of the shape and dating of the sealing mud.

Although only one or several pieces of sealing clay were unearthed from some tombs or ruins, they are of relatively unique value, and it is necessary to make a further statement here.

Figure 18 "The Messenger of the Emperor of Heaven" (taken from "Clearing of Han Dynasty Sites in Shaojiagou, Gaoyou, Jiangsu")

Jiangsu Gaoyou Wei Jin Religious Law Seal Clay. In 1957, the "Emperor Messenger" was unearthed from the Han Dynasty ruins in Gaoyou, Jiangsu Province (Figure 18). This is the first time that early religious sealing clay has been found in archaeological work. According to the writing characteristics of Fengni, its era should be in the Wei and Jin Dynasties. This judgment is slightly different from the age judgment held by the original report. From this, it was discovered that the "Yellow God Yuezhang" recorded in "Fengni Kaolue" (hereinafter referred to as "Kaolue"), the "Tiandi Huangshen □□" discovered by Le Lang, and the "Ghost Killing" unearthed in Miaoxi, Huzhou A series of religious seals of different periods, such as "Messenger" and multi-character script seals, and the "Yellow □ (God) Messenger Seal" unearthed from the Chachao-Ejin site in Vietnam (Figure 19), present their evolution process, scope of use and popular period. This system is a type of social function evolution of ancient Chinese seals, and it provides clues for thinking about the record of "Huangshen Yuezhang" in Ge Hong's "Baopuzi". The Huangshen seal unearthed from the Ejin site is also the first discovery in Jiaozhou of the Central Plains with Chinese characters sealed with mud. Its writing and printing style are consistent with the period attributes of the same tile image style, and it should be after the Eastern Jin Dynasty. This is the physical proof of the local spread and popularity of Taoist rituals in the Central Plains. Previously, Ye Qifeng wrote an article to discuss the issue of the handed down "Huangshen Yuezhang" and related ancient seals, and proposed that such ancient seals are "relics of the four historical stages of the middle and late Western Han Dynasty, Eastern Han Dynasty, Jin Dynasty, and Sixteen Kingdoms", and "should be obtained from the official seal system. Separation"; and pointed out that it should be named "Fulfillment Seal". The existing sealing mud unearthed in many places further confirms his opinion.

Figure 19 "Yellow (God) Messenger Chapter" (provided by Mariko Hiyamagata)

Seal clay of Jiangling and Jingzhou Warring States figures in Hubei. In 1978, two pieces of graphic sealing clay were unearthed from Tomb No. 1 in Tianxingguan, Jiangling, Hubei (Fig. 20). The pottery pots of the Baoshan Chu tomb, which was buried more than 20 years later, also contain clay seals with animal-shaped images (Fig. 21). In addition, in the silk quilt covering the coffin in the tomb, the sealing mud with the word "糹女" was found. This is the earliest clay seal found in China so far. Judging from the shape and usage of the sealing mud, no device for fixing the sealing mud has been found. It seems to be a relatively simple form, but the meaning of the use is very clear. Obviously, they are all used as a proprietary letter mark, and they are all used for sealing objects or transactions. This provides us with an answer to the function of early graphic seals, and also provides a new direction of thinking for exploring the early form of Chinese seals.

Figure 20 Graphical sealing clay (provided by Jingzhou Museum)

Figure 21 The pottery pots and the sealing mud of the mouth of the sealer unearthed from the No. 2 Chu Tomb in Baoshan (collected from "Baoshan Chu Tomb")

Figure 21 The pottery pots and the sealing mud of the mouth of the sealer unearthed from the No. 2 Chu Tomb in Baoshan (collected from "Baoshan Chu Tomb")

Figure 22 Sealing mud unearthed from the site of the Minyue King City in the Western Han Dynasty in Chong’an (provided by Fujian Museum)

Figure 22 Sealing mud unearthed from the site of the Minyue King City in the Western Han Dynasty in Chong’an (provided by Fujian Museum)

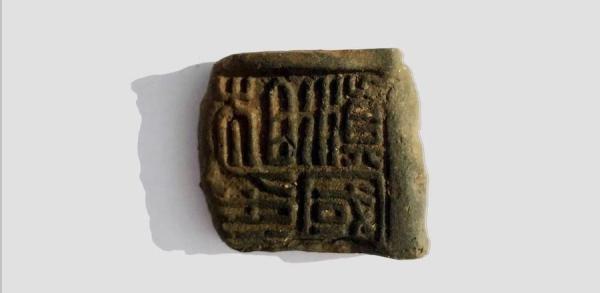

Fujian Chongan Minyue Kingdom Seal Clay in the Western Han Dynasty. From 1980 to 1986, three clay seals similar to private seals were discovered in the Chengcun site in Chong'an, Fujian Province (Fig. 22), of which the two complete seals reflect the same sealing form as that in the Central Plains. The printed text is a variant of Chinese characters, with Qin-style sidebars. The ruins of Chengcun are the King City of Minyue, which was destroyed in the period of Emperor Wu. Two seals with mutated Chinese characters were unearthed at the Chengcun site, which is an example of the Central Plains seal, the system of seals and the form of seal inspection, as well as the cultural elements of the Qin and Han Dynasties in the Minyue area.

Figure 23 "Wang Xingyin" (provided by He County Museum)

Guangxi, Guangdong Eastern Han and Nanyue Kingdom Seal Clay. From 1975 to 1976, the "Wang Xingyin" sealing clay was unearthed from Gaozhai Han Tomb in Hexian County, Guangxi (Figure 23). The clay seal unearthed from the Nanyue King’s Tomb in Guangzhou in 1983 (Fig. 25) and the Nanyue Palace Office site later, and the seal clay unearthed from the Shixiongshan site in Wuhua, Guangdong in 2011 (Fig. 26) have the same writing style, with clear and specific pen shapes , thus not only confirming their chronological relevance, but also showing that the seal characters in the tombs and ruins are all in the style of the Nanyue Kingdom, which reflects the regional coverage of the Nanyue Kingdom’s politics and culture from one aspect. Previously, two "sealed mud boxes" with characters were unearthed from Tomb No. 1 in Luobowan. These also show that the seals and seals in the Nanyue Kingdom inherited the Qin system in the Central Plains. The seal clay inscriptions on Shixiong Mountain ruled out the possibility that it was a site of the Qin Dynasty.

Figure 24 "Family Coward Seal" (Provided by Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Museum)

Figure 25 Emperor Seal (provided by the Nanyue King Museum of the Western Han Dynasty in Guangzhou)

Figure 26 The seal of Ding Brown (provided by Guangdong Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archeology)

Figure 27 "Chen Cong's Words" Clay Seal

Sealing mud of Wei and Jin Dynasties in Zhenning, Guizhou. In 2005, the "Chen Cong Yanshi" sealing clay was unearthed from the Tianjiaojiao site in Liangtian Township, Zhenning Miao Autonomous County, Guizhou Province (Figure 27). This is the first time that Chinese characters have been found in Guizhou. The shape of the clay seal is a typical C shape, and it should be from the Wei and Jin Dynasties in terms of the Indian style and writing style. This is an important demonstration of the connection between the local existence and the Chinese character culture of the Central Plains.

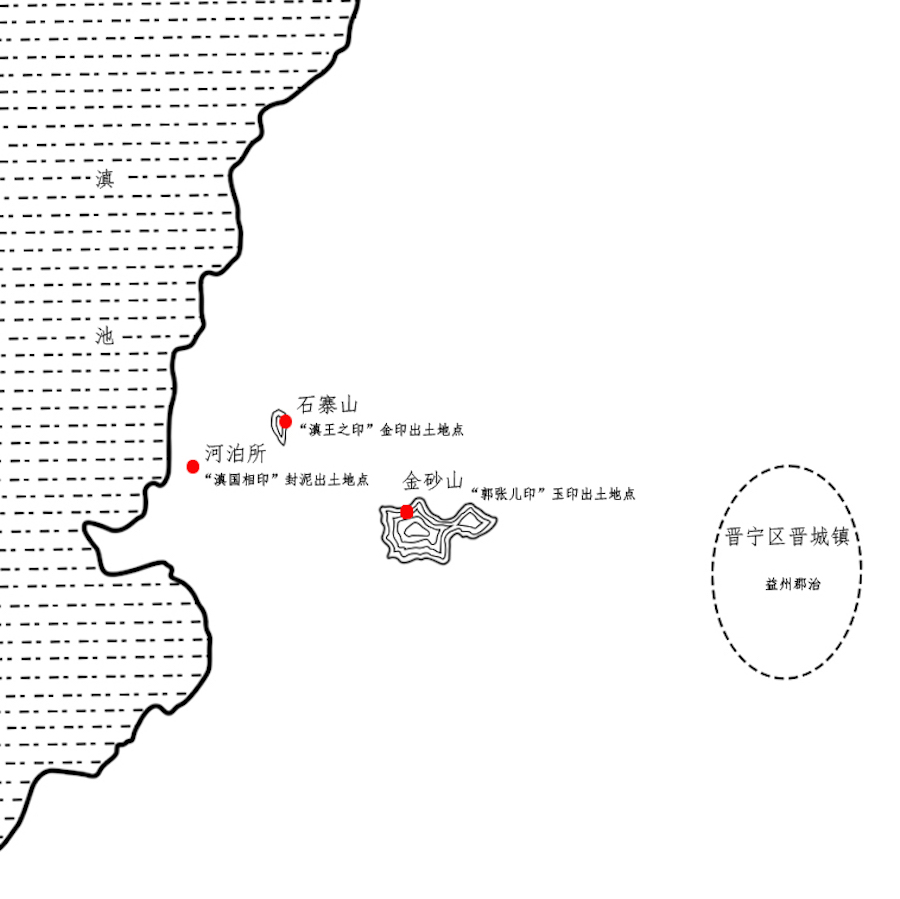

Figure 28 Schematic diagram of the location of the Hebosuo site (painted by Liu Dewu)

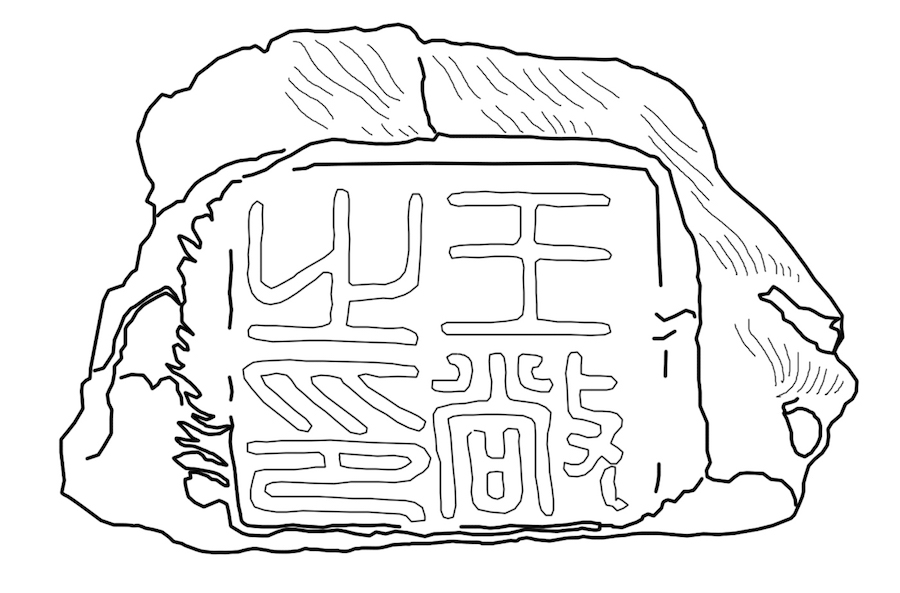

The seal mud of the Dian Kingdom in the Western Han Dynasty in Jinning, Yunnan. From 2018 to 2019, the "Dian Kingdom Xiangyin" (Figure 29) and "Wang Chang's Seal" (Figure 30) "Tian Feng's Private Seal" and "Eren Xuan "Wait to seal the mud. This is the first archaeological unearthed clay of the Han Dynasty in Yunnan. The seal is in the calligraphy and casting style of the official private seal of the Central Plains, and the shape of the clay seal is B1 type. According to a comprehensive judgment, its age should be from the middle to late Western Han Dynasty. The excavation of the above-mentioned official and privately sealed mud reveals the dual elements of the cultural attributes of the Dian Kingdom site in Hebo and the continued existence of the Han ethnic group. At the same time, it also provides us with a further understanding of the nature of the "Dian Kingdom", its relationship with the Central Plains Dynasty and its duration , providing a very important basis.

Figure 29 "Prime Minister of Dian Kingdom"

Figure 30 Copy of "Wang Chang's Seal"

The period from the Warring States Period to the Wei and Jin Dynasties was the period when the sealing method of seals and seals was widely used. In recent decades, ancient mud-sealing objects with the remains of the Qin and Han dynasties as the main body have been discovered in various provinces and autonomous regions except Tibet, Qinghai, Heilongjiang, Ningxia, Jilin, and Hainan, and most of them belong to the records of archaeological excavations , which provides new academic conditions for contemporary mud sealing research.

3. Discovery of several other sealing mud groups

The end of the 20th century was the period when the largest number of non-archaeological seals were unearthed and the location was relatively clear. Influenced by the study of ancient seal seals, the art creation of seal cutting, and the publication of collections of sealing clay materials, the collection trend is active. Most of the scattered objects discovered and excavated in this period were hidden by individuals, and while they were preserved and disseminated in a timely manner, it also brought about the loss of scientific information and the dispersion of materials.

After the end of the 1990s, besides the aforementioned Xi’an Xiangjia Lane, Liucunbao, and Chuangaoling, other sites where mud seals were unearthed concentratedly, a large number of mud seals were found in the following places:

Henan Xincai Warring States Chufeng mud group. In 2001, hundreds of clay seals of the Warring States period were unearthed in Xincai, Henan, mainly in Chu script, which was the largest discovery of clay seals of the Warring States period since records began. "A Preliminary Investigation of the Sealing Mud in the Eastern Zhou Dynasty in the Old City of Xincai" disclosed the location where the sealing mud was found, and discussed the characters and the nature of the sealing mud. Dong Shan's "Revision of the Explanatory Inscriptions Unearthed from the Chu Seals in Xincai" also revised some texts and made new research and interpretations. There are not many items of clay seals produced. In addition to the seals of famous officials in Chu and the seals related to city trade and taxation, there are also a few private seals of the Three Jin Dynasty and the early Western Han Dynasty. Since the location of the discovery is relatively clear, it provides a basis for judging the nature of the site, and it also has specimen significance for understanding the characters and morphological special evidence of the Chu seal clay in the Warring States Period.

Linzi, Shandong Province, Qi State Fengni Group in the Western Han Dynasty. Around 2003, the number of clay seals unearthed in Linzi that were published successively has exceeded the sum of those unearthed before the 1940s. Most of the categories coincide with those unearthed in the early years, mainly belonging to Liu Fei Qi State and its subordinate county, county, and township official seals in the early Han Dynasty. There are also a few texts that show that the upper limit of the era is the Warring States Period, and the lower limit is the middle and late Western Han Dynasty and the early Eastern Han Dynasty. It is said that the excavation site of some of the Qi official seals in the Warring States Period in this area is different from the area where the Han seals were found (Figure 31).

Figure 31 Liujiazhai in Linzi

The ranks and names of officials and place names newly released in the Han Dynasty have also been extended compared with the previous ones, and some of the official seals of the Han County after Emperor Jing's cuts appeared. "Research on Fengni of Qi State in Linzi Newly Published in the Western Han Dynasty" believes that the Linzi Fengni Group has the most sufficient information on restoring the official system of the vassal kingdom.

Figure 32 The ruins of the State of Shen near Pingyu Ancient City Village

Henan Pingyu Qin Han Runan County Fengni Group. Around 2005, it is said that thousands of seals from the Qin, Western Han, Eastern Han and Wei Jin Dynasties were unearthed in Pingyu Gucheng Village, Henan Province (Figure 32). "Historical Signs of Xinjian Fengni Group in Runan County of the Han Dynasty" made a textual research on the era of Fengni and the eradication of Hou Guo in Runan County in the Eastern Han Dynasty.

This is a typical remains of the mud seals of officials in the inner county. According to the information seen, the unearthed mud seals cover but not much beyond the counties under the jurisdiction of Hanrunan County and the officials of the Marquis in the county. Therefore, the seal mud group can be named as the county. Name it to clarify its characteristics. The ascending nature of the sealing mud excavated from this site is clear, so it can be seen that Gucheng Village should be the site of the Ru'nan county government in the Qin and Han Dynasties. Later, a small amount of official seals from the Qin Dynasty and private seals from the Wei and Jin Dynasties were unearthed in succession, so it is inferred that there should be many accumulations in different periods at the site.

The Fengni Group of the Western Han Dynasty in Jiaojia Village, Xi'an, Shaanxi Province. It is said that hundreds of pieces of clay seals from the Western Han Dynasty were unearthed here. According to Ma Ji's "Investigation of the Land Excavated from Sealed Mud in Recent Years in Xi'an", the site of the unearthed mud sealed is located about 200 meters south of Jiaojia Village. "Compilation" records 144 clay seals "unearthed in Zhuanjiaojia Village", including the official seals of officials in the central government such as the servants of the Western Han Dynasty, Shaofu, Jiang Zuo, and Nei Shi, as well as official seals from Yandao and Jialingdao in Shu County It may be inferred that this place was the seat of a central government office in the Western Han Dynasty, which is similar to the connotation of some of the mud seals compiled in "Kao Lue". This is the first concentrated discovery of official seal clay of the Western Han Dynasty since the 20th century.

It is said that in recent years, the site of Weiyang Palace in Xi'an and the site of Jingshicang in Huayin have also been discovered successively, but the quantity is unknown. According to some known materials, the former is mainly the seal clay of Zhuyu Kingdom and Hanjun and county officials in the early Western Han Dynasty. Among them, the concentrated appearance of seals and seals of several king seals, county guards, and county lieutenants indicates that the land should be a more important official office for receiving items from the county.

It is said that it was unearthed from the sealing mud of Lujiakou in Xi'an, Shaanxi (provided by Ma Ji)

Xinmangfeng mud group in Lujiakou Village, Xi'an, Shaanxi Province. In 2009, it was reported that more than a thousand pieces of Western Han and Xinmang clay seals were unearthed in Lujiakou Village, Xi'an, Shaanxi (Figure 33). According to Ma Ji's investigation, the unearthed land is several hundred meters west of the ruins of the front hall of Weiyang Palace.

The main part of the excavation in this place is the official seal of Xinmang, which has been seen in Yang Guangtai's "Compilation" and Ma Ji's "Xinchu Xinmang Fengni Xuan". The clay seal preserves a lot of Xinmang central government, local prefecture and county official names and fifth-rank titles that have not been recorded in historical records. It is by far the most abundant physical historical material reflecting Wang Mang's official system and county and county reforms. Accordingly, this place should be the seat of a central government office that continued to Xinmang at the end of the Western Han Dynasty. The author's "New Evidence of Wang Mang's Official Officials" and Ma Ji's "Summary of the New Mang Seals in Lujiakou, Xi'an" are both based on the changes in Wang Mang's central government, ministries, prefectures, and county officials seen in Lujiakou. Sort out the rationale and textual research.

Fengni Group in Han Hongnong County, Hangu Pass, Lingbao, Henan. Around 2011, it is said that a large number of Qin and Han sealing mud were successively unearthed from the Hanguguan site in Lingbao, Henan (Figure 34), but the quantity is unknown. The sealing mud comes from a high slope in Wangduo Village, and there are still broken tiles and bricks scattered. The excerpts are based on the official seals of Hongnong County officials and county officials in the Han Dynasty, and the same as those in Gucheng Village are seals that mainly reflect the administrative activities in the county. Xu Xiongzhi/Gu Songzhang's article "A Preliminary Discussion on Fengni in Hongnong County of the New Han Dynasty" made a research and analysis on the age of the mud from this place and the geographical historical materials involved.

Figure 34 Lingbao Hanguguan Ruins

Qin and Han Fengni Groups in Yuwang Township, Xia County, Shanxi Province. It is said that around 2016, a batch of sealing mud was unearthed in Yuwang Township, Xia County, Shanxi Province, the quantity is unknown. As far as we can see, some of the mud seals include things from the Qin and Western Han Dynasties, mainly the seals of county officials in Hedong County in the Western Han Dynasty, and the site should also be the site of the county and county government offices that continued from the Qin Dynasty to the Western Han Dynasty. According to this compilation, "Hewai Tiecheng", an ad hoc official of Hewai County, appears in the mud seals of Yuwang Township, Xia County (Figure 35), which can be related to Liucun Baosuo in the "Selected Edition of Xin Chu Tao Wen Feng Ni". The "Hewai Fucheng" (Figure 36) and other mutual evidences that Qin once owned its county.

Figure 35 "Hewai Tiecheng" (collected from "Selected Collection of Ancient Seal Clay in Jianyin Shanfang Collection")

Figure 36 "Hewai Fucheng" (taken from "Newly Released Pottery Wen Fengni Selection")

The above discovery sites are all ruins. The number exceeds that of early unearthed and archaeological excavations.

From the archaeological excavations unearthed before the 1950s and published thereafter, together with the scattered mud seals unearthed in many places since the 1990s, the total number of mud seals (including fragments and the same text) in existence should be 30,000 according to preliminary investigations above. The era involved is from the middle period of the Warring States Period to the Southern Song Dynasty. Among them, the quantity and category of seal clay from Qin and Han Dynasties are the most abundant. In recent decades, the discovery of clay seals in Qin and Han Dynasties has exploded, and the combination of seal seals unearthed in the late Qing Dynasty and the Republic of China is a more complete physical data system in terms of time sequence and more complete forms and categories. unprecedented conditions.