Unusual in the British museum landscape, the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge houses more than half a million artifacts, from Bronze Age pottery to Titian masterpieces. Of course, as a university museum, it plays multiple roles—although it is not on the same level as a national museum, it has a larger public platform than ordinary academic institutions. The importance and quality of the collections of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge is also rare among university museums.

Luke Syson, the current director of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, started his career as curator of medals at the British Museum, and he was also the curator of Da Vinci: Painter of the Holy See of Milan in the National Gallery in 2011. As for appreciating paintings, he believes that the age of screens has made attention accustomed to a framed experience. In museum exhibitions, the relationship between works on shelves and works in space must be adjusted.

Fitzwilliam Museum Director Luke Sisson

Inside the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

The Fitzwilliam Museum is an art and archaeological museum named after its founder, Richard Fitzwilliam, VII Viscount Fitzwilliam of Merrion.

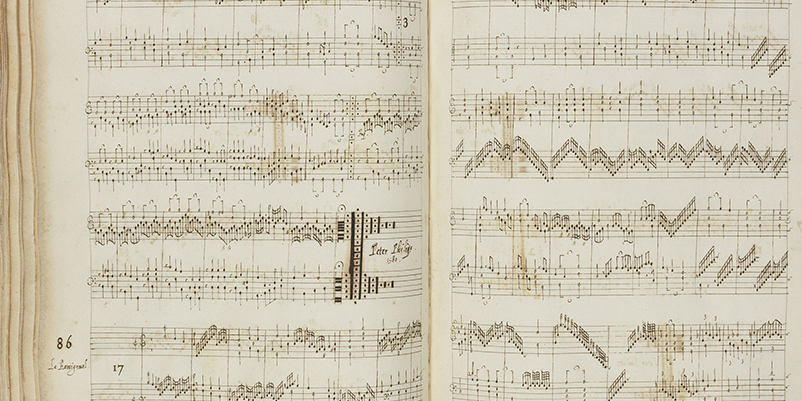

Richard Fitzwilliam entered Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1761. He inherited from his maternal grandfather a large collection of 17th century Dutch paintings, in addition to a large collection of Old Master prints. Richard himself has a strong interest in music, for which he traveled around Europe and collected a large number of hand-copied and early printed scores.

Early 17th century sheet music.

However, these collections are not yet sufficient to form the basis of a museum collection. Richard's most important collecting opportunity came in 1798-99, when he sold paintings from the Ohlins collection in London. He tried to buy all the works privately, but failed. He did, however, buy several masterpieces from it, including Venus, Cupid and the Lutheran by Titian, a master of the Venetian school of Renaissance painting, and Hermes, Herse and Argentine by Veronese. Gloros.

Titian "Venus, Cupid and the Lute Player"

To house this extensive collection of books and manuscripts, paintings and prints, Richard established the museum, which he bequeathed to his alma mater, the University of Cambridge, upon his death.

Although in terms of scale, the Fitzwilliam Museum is not comparable to the large national museums, but the huge exhibition hall of Italian oil paintings surpasses some large museums, and its exhibition hall of 18th century European porcelain is also something that the museum has not yet paid attention to. By the 19th century, the museum's collection was growing thanks to various donations. In 1823, the explorer GB Belzoni donated the lid of the sarcophagus of the ancient Egyptian pharaoh Ramses III (1184-1153 BC). The Roman sculptures donated by John Disney in 1850 and the ancient Greek pottery vases, coins and jewelry from the Lick collection purchased by the museum in 1864 have witnessed the emphasis placed on the study of classical civilization by Western academic circles in the mid-19th century.

The granite sarcophagus lid of Ramses III.

By the end of the 19th century, in the face of increasing collections, museum display and collection space had begun to become a major problem. The problem was not resolved until 1908, when Sidney Cockerell was the curator. He received a large and generous gift from Charles Brinsley Marley in 1912, which included Titian's Tarquin and Lucretia, one of the museum's true treasures. In 1915, Cockrell decided to create a courtyard on one side of the original building, where Cockrell's talent for display design could be fully utilized. He combined paintings with furniture, carpets and other decorative arts, and arranged them in a domestic interior environment, which is still maintained today.

Italian Renaissance Exhibition Hall, the unique golden wall of this exhibition hall was chosen by Sidney Cockrell, the curator from 1908 to 1937.

However, the Fitzwilliam Museum was relatively late in accepting modernist art, and only began to have French Impressionist paintings in 1939; since then, the number of modern art works has increased year by year, and it has begun to have works such as Matisse, Picasso and Braque.

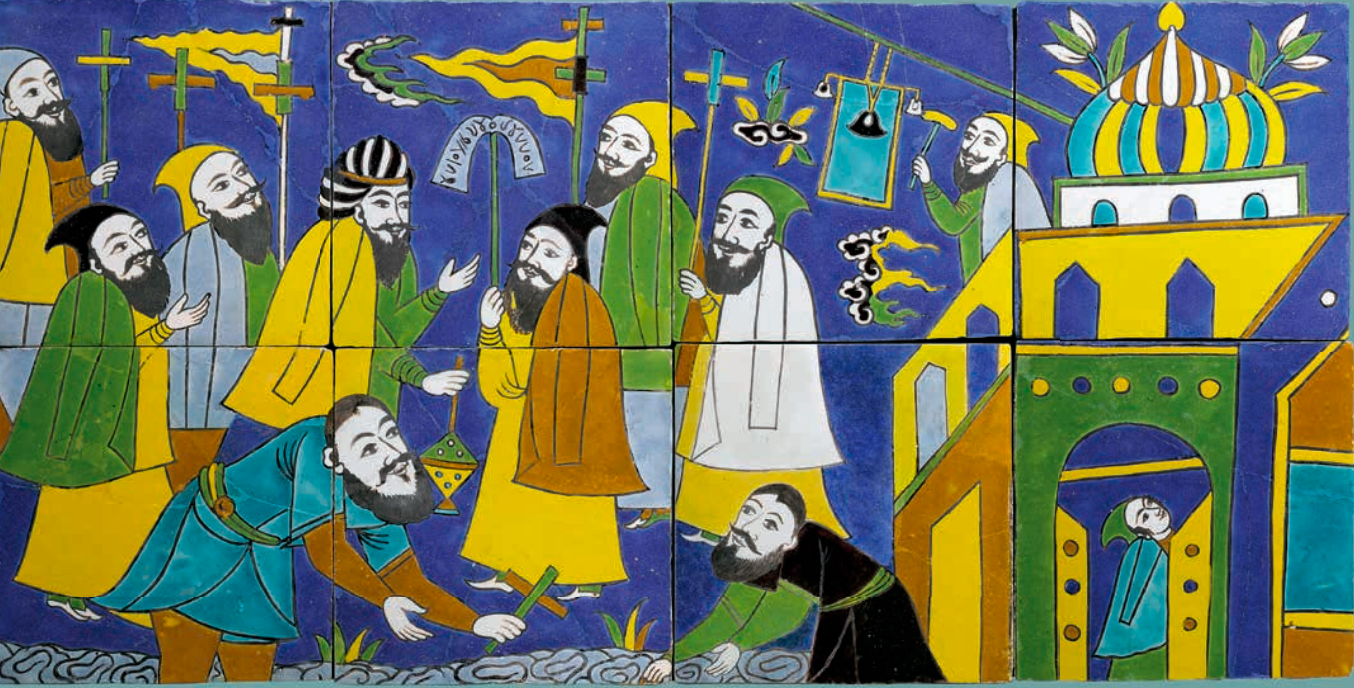

The latest expansion of the museum was in 2004. Today, the collections of the Fitzwilliam Museum range from the ancient Mesopotamia, ancient Egypt, ancient Greece and Rome, to the European art of the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and the 17th and 18th centuries, as well as Western modern and contemporary art. Art. There is also a separate Chinese art exhibition room in the museum, where there are bronze wares from the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period, as well as porcelain wares from the Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties.

Oriental Art Exhibition Hall

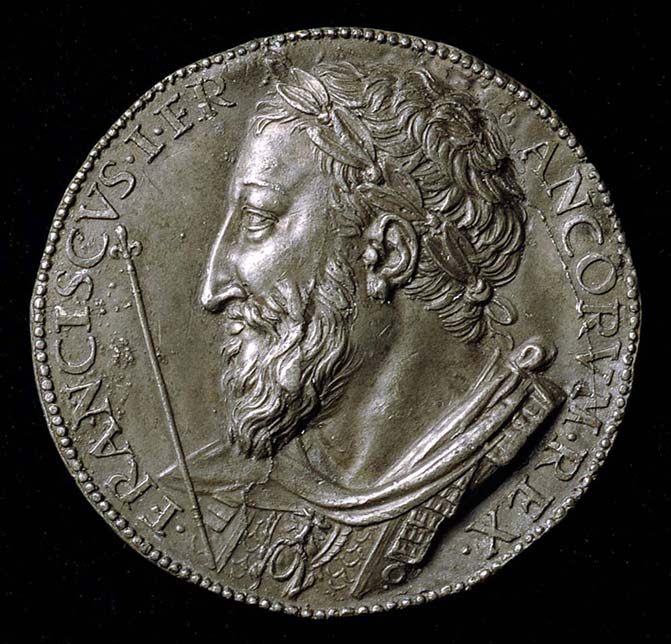

The current curator, Luke Sisson, took office in 2019. For the curator, currency is usually not the beginning of everything, but for Sisson, it is especially important. On the one hand, it was because the Arts Council England announced a 50% cut in funding for the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge last November, and on the other hand, Sisson began his career as a medal curator at the British Museum. Therefore, different types of "currency" have become an unavoidable topic for dialogue with Sissen.

Sissen's research on currency can be traced back to his doctorate in royal portraiture of Milan, Ferrara and Mantua in the 15th century at the Courtauld Academy of Art. One day, while researching my doctoral dissertation in the reading room of the British Museum, I sat next to the art historian Ronald Lightbown. Letterburn was then conservator of metalwork at the V&A, but he is best known for his large monograph on the Italian Renaissance painters Botticelli, Carlo Crivelli, Mantegna famous.

Sisson asked him about Mantegna's research. Sisson describes himself as never having done so - because "I'm very shy". Letterburn graciously answered questions and suggested tea. Sisson then proceeded to boldly present his theory of Mantegna research, which Wrightben thought was entirely wrong, and suggested that Sisson look at the portrait of the medallion. That advice turned out to be important not only for Sissen’s PhD, but also for Sissen’s understanding that “if you want to understand larger, more unconventional problems, it’s fruitful to look for clues of subtle connections between media in a given period.” Finding connections in stories has been a hallmark of Sissen's work since then.

The Order of Francis I of France, designed by the Florentine goldsmith and sculptor Benvenuto Cellini, Titian depicted Francis three times but never actually saw him in person. The medal had a huge impact on him.

Over the past 20 years, many of the world's leading museums have sought new forms of presentation, with the aim of showing the connections and the stories behind the connections. Sissen has been involved in some of these prestigious gallery projects at various stages of conception and delivery, such as the British Museum's Enlightenment Gallery and the V&A Medieval and Renaissance Gallery in 2003. Although he modestly said: "(The latter) I only participated in six months." However, it is clear that his planning work with Peta Motture (Senior Curator at V&A) and others has determined The appearance of the showroom. As director of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Sisson initially worked with Ellenor Alcorn on the refurbishment of the Met's UK gallery, which was restored after Sissen moved to Cambridge in 2019. To be completed in March 2020 by the follow-up principal.

Because of this, Sisson was instrumental in considering how Art Deco could be displayed in the most effective way. As he puts it, "the combination of painting (and easel art more broadly) with objects in space has always been difficult." Not for aesthetic reasons, but because "they have different ways of seeing, of interacting with the viewer. And very different.” In Sisson’s view, this problem may be exacerbated by contemporary lifestyles: “With the work on the wall, the experience is framed, [the viewer] places himself in a fixed viewing position, which is We are more familiar in the age of screens." The artist provides us with a "window to an alternative world", and "anything else you touch (such as sculptures, utensils) is an invasion of the existing world."

Few viewers would shy away from approaching the picture to appreciate the brush strokes, but "it is not the case when approaching the sculpture, because the three-dimensional space of the sculpture itself requires a larger field of vision to watch." "Although the objects in the space have more influence on the audience, when the handle When online art and spatial cultural relics are displayed together, there is a natural comfort in viewing paintings, which means that the cultural relics displayed in the space are secondary to the works on the wall.”

Greco-Roman Gallery, Bust of Antinous

Sisson sought to confront these questions directly when conceiving the British gallery at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art. "My original idea was to pretty much get rid of paintings. But my successors changed that, and they introduced more paintings than I could have imagined." Nevertheless, the Met is now telling about Britain and its collections in innovative ways The story clearly bears Sisson's stamp.

At the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, how to answer the question of displaying collections in a slightly different way. It’s about “building them: finding the frame, finding the light” and “engaging the audience in an almost telling way,” Sisson said. “While some viewers like the ceramics gallery at the Fitzwilliam Museum, we don’t have enough clues as to where to stop,” he admits. Providing "focus" exhibits is clearly next on the museum's agenda.

European and Japanese ceramic exhibition hall

Changing a visitor's perception of a work is what university museums are good at. Because one of the richnesses of university museums is “bringing a rich disciplinary approach to the collection,” Sisson means, curatorial teams aren’t the only ones shaping the museum’s narrative. "There's a feeling that when you're working with academics, you can present a more distinctive exhibition," he said. The Fitzwilliam Museum has several special exhibitions that are examples of academic papers being transformed into visual exhibitions, and the flexibility of university museums allows such The exhibition is more comprehensive.

Innovation doesn't just come from museums, but from wider community engagement. Most recently, the Fitzwilliam Museum, in partnership with the University of Cambridge, sent Egyptian coffins and artefacts to Wisbech in Cambridgeshire for display. Dilapidated Georgian buildings and the manuscript of Dickens' Great Expectations at Wisbech & Fenland Museum are evidence of its illustrious past, but today it has one of the highest unemployment rates in England. “What university museums can do is build broad intellectual bridges and connect with local, regional, national and international audiences to achieve different types of impact,” Sisson said.

Cambridge Fitzwilliam Museum

Space, however, was a major challenge for the Fitzwilliam Museum. The conservation and research of part of the museum's cultural relics is currently carried out at the Hamilton Cole Institute in Whittlesford. But the institute should be closer to the museum. "A better storage space for cultural relics provides access for scholars and allows more interaction between cultural relics researchers and conservation scientists."

Returning to Sisson's vision for a university museum, the Fitzwilliam Museum as a place to share knowledge, he did not want to build a grand new building, but rather repurposed unused buildings that Fitzwilliam College could utilize. He hopes to realize this idea before retiring in ten years, and he hopes that more new audiences will talk to the museum.

Note: This article is partly compiled from an interview between Edward Behrens and Luke Sisson in Apollo Magazine about how it will reshape the future of museums.