"Beautiful Landscape: Collections of the National Archaeological Museum of Naples" is currently being exhibited at the Pudong Art Museum in Shanghai. About 70 collections from the National Archaeological Museum of Naples, Italy, and the ancient Roman civilization more than 2,000 years ago have reproduced the brilliant civilization from different aspects. . Of particular importance are the frescoes from Pompeii.

In 79 AD, Mount Vesuvius erupted, destroying Pompeii and its surrounding city Herculaneum overnight. A large amount of volcanic ash has completely preserved the remains of the two cities, providing archaeologists and historians with extremely important research materials.

The National Archaeological Museum of Naples has the world's most complete and important collection of frescoes from Pompeii and Herculaneum, as well as various artifacts unearthed in the ancient city. "The Paper" traces back the belief and life more than two thousand years ago through cultural relics.

Landscape, Herculaneum, painted fresco, 1st century

The frescoes provide a starting point for understanding Roman antiquity. Examine these paintings not only as decorations that reflect the taste of the city, but also as the work of the artist. It's just that these artists were regarded as craftsmen at that time, and their own views and attitudes were not recorded and preserved.

Literary evidence from Pliny the Elder (23-August 24, 79, ancient Roman writer, naturalist, statesman) suggests that educated Romans considered contemporary frescoes inferior to ancient Greek painters of the 4th-5th centuries BC. The latter is considered to serve the public interest, while the Romans imitated the works of the Greek period on the wall, mostly just to decorate their homes.

There are four styles of frescoes in Pompeii, the first of which is hardly a painting, but a simple layer of plaster that gives the impression that the entire wall is inlaid with expensive imported marble. The second is the originality of Rome. The interior walls are dressed up as charming gardens or corridors in an attempt to extend the space. But this visually logical and simulated style became tiresome around the last decade of the first century AD, and a third style was created, emphasizing the smooth and limited nature of walls, favoring intricate detail. The fourth style seems to be a combination of a sense of space and refined elegance, and the mural painter still keenly captures the audience's expectations with his masterful control of shape and color.

Detail of a menorah, Pompeii, painted fresco, 1st century

One of the curators of this exhibition, Italian archaeologist Mario Grimaldi (Mario Grimaldi), in an exclusive interview with The Paper, divided the mural themes of the exhibition into "mythical stories, epic and dramatic poems, daily Life scene", "especially the daily life scene is a colorful world that restores the color of clothing."

Tribute women and statues, Herculaneum, painted fresco, 1st century

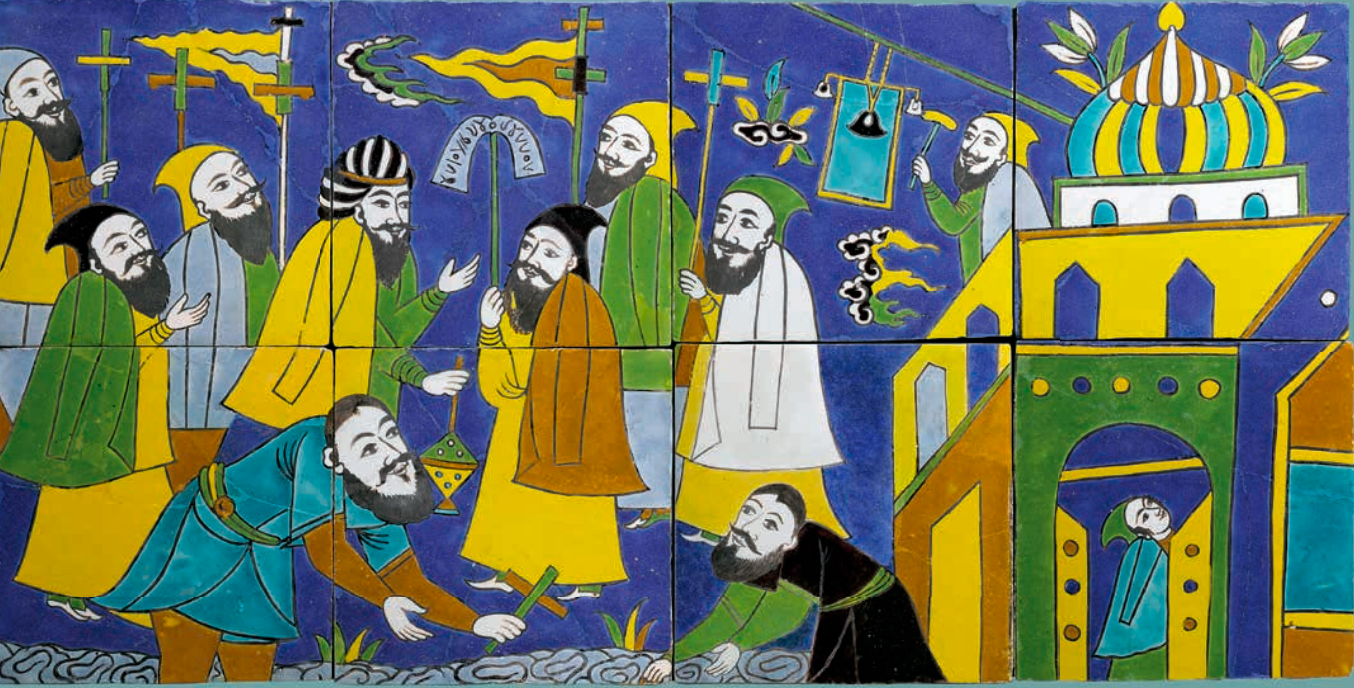

Myths and Epics, Ancient Rome in which a Man-God Dialogues

The most striking thing in the exhibition is a mosaic mural "Lion and Dionysus Procession Scene", which was unearthed in 1829. This gorgeous and exquisite mosaic is located in the center of the floor of a spacious restaurant, and the decoration on the surrounding walls can be traced back to Augustus. The period (the third style of Pompeian frescoes), exhibited in its original state, is located in the center of a separate dark hall.

Exhibition site, the ground is a stone mosaic of "Lion and Dionysus Procession Scene Mosaic", 1st century BC

Mosaic of Lion and Bacchus procession scene, Pompeii, Stone mosaic, 1st century BC

Bordered by delicate and colorful folds, this mosaic depicts the interior of a temple of Dionysus: Dionysus, priestesses, and Cupid surround a bushy mane, lion with a wreath. Wearing gold chains on its forelegs, the sacred beast seems overwhelmed by the power of the surrounding music and apparitions of Dionysus. The technique used here is called worm patterning, and it uses tiny inlays just 3mm wide. The image on the mosaic is a direct reference to a sculpture by Alexilaus (The Lioness Playing with Cupid), which Caesar built in his piazza, suggesting its prototype dates from the first century BC .

Sphinx standing on the edge of a carpet, Pompeii, painted fresco, 1st century

Originally derived from ancient Egyptian mythology, the Sphinx is a winged monster, usually male.

Unlike Egyptian male sphinxes, Greek sphinxes usually appear as females. She has the head of a woman, the body of a lion and the wings of a bird. Also, in ancient Egypt the Sphinx was considered benevolent, but in Greek tradition she was portrayed as perfidious and ruthless, killing and eating those who could not answer her riddles. This deadly sphinx appears in the myth and drama of Oedipus. Whether in ancient Egypt or ancient Greece, the Sphinx was considered a guardian and was often associated with architectural forms such as royal tombs and religious temples. Depicting intricate details, this work belongs to the third style of Pompeian frescoes.

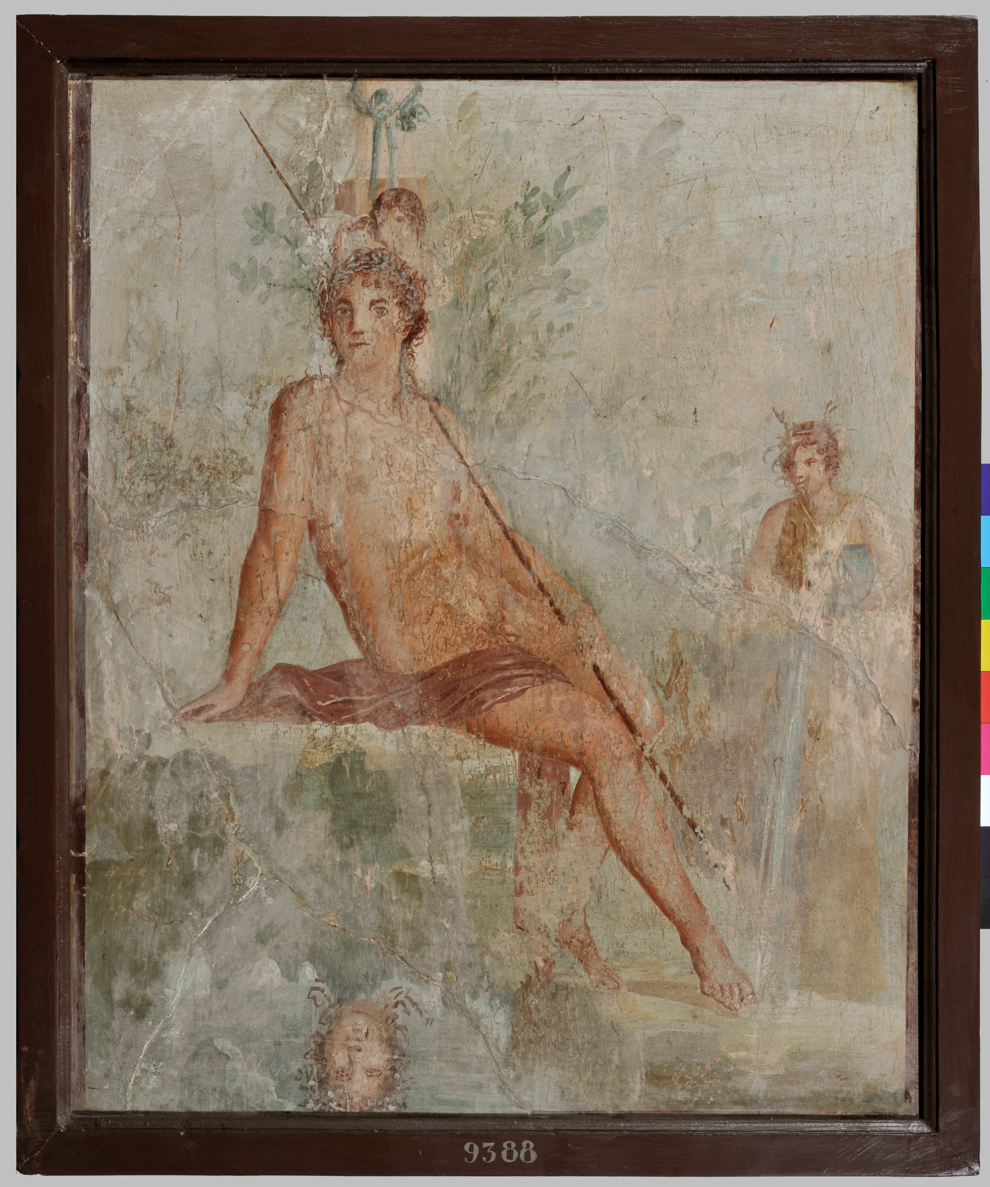

Narcissus and Leda and the Swan in the exhibition come from ancient Greek mythology.

Narcissus is a beautiful young man in ancient Greek mythology. One day he found his own shadow in the water, but he didn’t know that it was himself. For daffodils. To this day, in Greece, the daffodil is called Narcissus.

Narcissus, Pompeii, painted fresco, 1st century

Leda and the Swan is a story and artistic subject in Greek mythology. In Greek mythology, Leda was a princess of Aetonia who became queen of Sparta after marrying King Tyndareus of Sparta. According to Ovid's description, the god Zeus, out of love for Leda, turned into a swan to seduce her. Later Leda laid two eggs, from which two boys and two girls hatched, one of whom was Helen.

Leda and the Swan, Pompeii, painted fresco, 1st century

Leda and the Swan was a famous myth throughout the Middle Ages, but during the Italian Renaissance it became even more prominent as a classic subject with erotic overtones. The three masters of the Renaissance - Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael - have all depicted this theme, and the father of modernism, Cézanne, has also reinterpreted it.

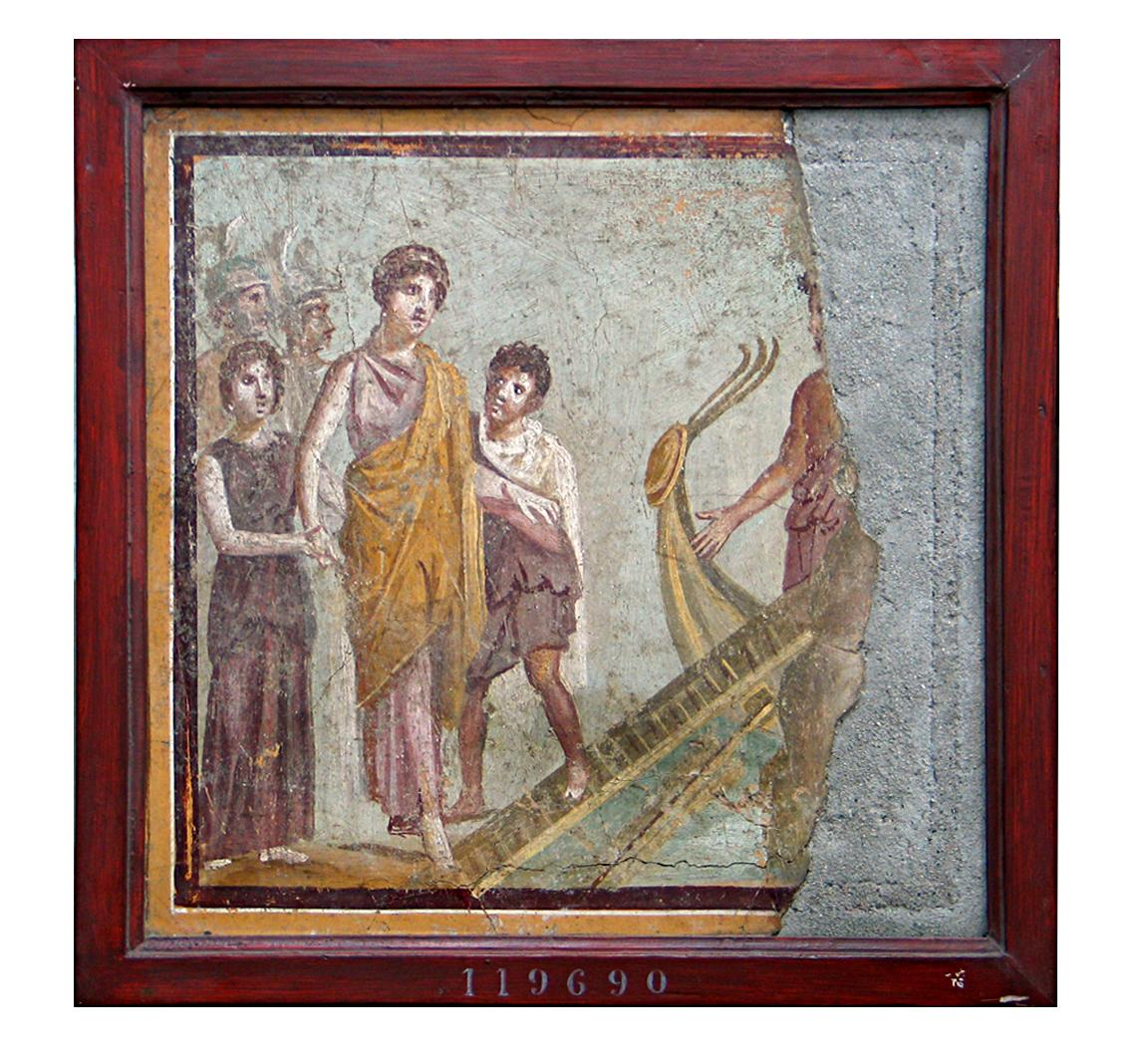

The Departure of Helen, Pompeii, painted fresco, 1st century

Helen is a character in Greek mythology, said to be the most beautiful woman in the world. In the golden apple dispute, Zeus appointed Paris, the little prince of Troy, to judge Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite as the most beautiful goddess. To win Paris' favor, Aphrodite promised him the most beautiful woman in the world. When Paris brought back Helen, the wife of King Menelaus of Sparta, back to Troy, the Greeks declared war on Troy in order to regain Helen. This was the trigger of the famous Trojan War.

Helen's beauty inspired artistic expression throughout the ages, and she was often the embodiment of ideal human beauty. Images of Helen first appear in the 7th century BC. Her abduction by Paris or her escape with him was a popular theme in ancient Greece. In medieval illustrations, the event is often depicted as a seduction; in Renaissance painting, it is often depicted as an abduction.

In ancient Roman religion, the goddess Victoria was the personification of victory. She first appears during the First Punic War and appears to be a romanization of the ancient Greek goddess Nick, the goddess of victory associated with the Roman mainland of Greece and the allies of Magna Graecia. Since then, Victoria has symbolized the ultimate hegemony and domination of Rome. The king of the mural "The Goddess of Victory and the King Before the Spoils of War" is the famous Alexander the Great, the king of the Macedonian Kingdom in the northwest of ancient Greece. Since inheriting the throne from his father Philip II at the age of twenty, he has carried out unprecedented large-scale military conquests, and by the time he was thirty, he had established a huge empire. Undefeated on the battlefield, he is considered one of the greatest generals in history.

Victory and King before the Trophy, Pompeii, painted fresco, 1st century

In the murals, the characteristic horned helmets and oval shields are Gaul weapons as trophies. The ax held in the right hand of Nick, the goddess of victory on the left, is also regarded as a trophies, while Alexander on the right is a young man who has just been crowned. The ruler, whose chest is protected by the armor of a Macedonian king, is instantly recognizable by the gorgon decoration on it and the helmet at his feet. He holds the Macedonian spear in his left hand and the army commander's scepter in his right.

Record daily scenes and look back at life two thousand years ago

A well-known claim is that Pompeii was an insignificant backwater in the Roman world. It is generally believed that when major historical events occurred in Rome, the Pompeians tended to live their days without any disturbance.

Archaeologists have two different attitudes toward Pompeii's insignificance. Most historians regret that Pompeii, the only city in the Roman world preserved at such a level of detail, is so far removed from mainstream Roman life, history, and politics. Others, by contrast, celebrate the city's mundaneness, arguing that it is precisely because of this that we are fortunate enough to understand the lives of the inhabitants of the ancient world today.

For example, their sacrificial life. Especially the sacrifice to Dionysus.

Tribute women in buildings, Herculaneum, painted fresco, 1st century

The god of wine, Dionysus, was the god of wine. He not only possessed the intoxicating power of wine, but also became a very charismatic god at that time by giving joy and love. He is also the god of drama, and is in charge of the fertility and reproduction of the earth, and the death and rebirth of human beings.

And his priestess (that is, his maid attendant) means "madman" or "crazy" in ancient Greek mythology. They may have originated from the aristocratic women who first worshiped Dionysus, and later more and more commoner women joined them-some were persecuted, and some followed voluntarily. A woman who follows Dionysus, in the Dionysian ceremony, will drink revelry, and use the power of alcohol to enter a state of madness and confusion, and liberate herself. According to Aristotle's records in "Poetics", tragedy originated from the celebration performances in honor of Dionysus.

Tragic mask, Pompeii, painted fresco, 1st century

The custom of offering sacrifices to the God of Dionysus was introduced to Greece from Egypt in the 13th century BC, and the worship of the God of Dionysus only became popular in Greece around the 8th century BC. At first, the center of Dionysus worship was in Naxos, and later Mount Catajon in Boiotia became a place for Dionysian carnival sacrifices, which soon spread throughout Greece from south to north. Pausanias, a Greek geographer in the Roman era in the second century AD, recorded in the "Description of Greece" (Description of Greece) about the carnivals of worshiping the god of wine in many places in Greece, the Aegean Islands, and Asia Minor. Activity.

Bacchus priestess fresco, Herculaneum, painted fresco, 1st century

At first only women participated in the procession dedicated to Dionysus. Early followers of Dionysus were only the three goddesses of Grace, but later his followers were changed to Dionysian Madame Minades and Pan, the god of fauns. Women participating in the Dionysian sacrifice procession usually wear ivy crowns and fawn skins, hold a Dionysian staff wrapped in ivy and topped with pine cones in their hands, beat tambourines and cymbals, and dress up as a Dionysian woman .

Still Life with Bacchus Statue and Tribute Plate, Herculaneum, Painted fresco, 1st century

There are also frescoes presenting tributes to Dionysus, the god of wine. In the painting, a majestic gilded bronze statue (similar to the family patron saint in the exhibition) was made in the image of Dionysus, and a branch of myrtle was placed in front of him. The Dionysian statue rests on a flat surface (possibly an altar), with other offerings in the foreground of the fresco, such as a silver cup containing remnants of wine, a sheep's head, and a bronze flagon. Behind them is a large rock on which a bronze dish with a hinged handle is laden with various fruits: pine cones, pomegranates, figs and dates.

Flagon with a horse's head, Vesuvius, painted fresco, 1st century

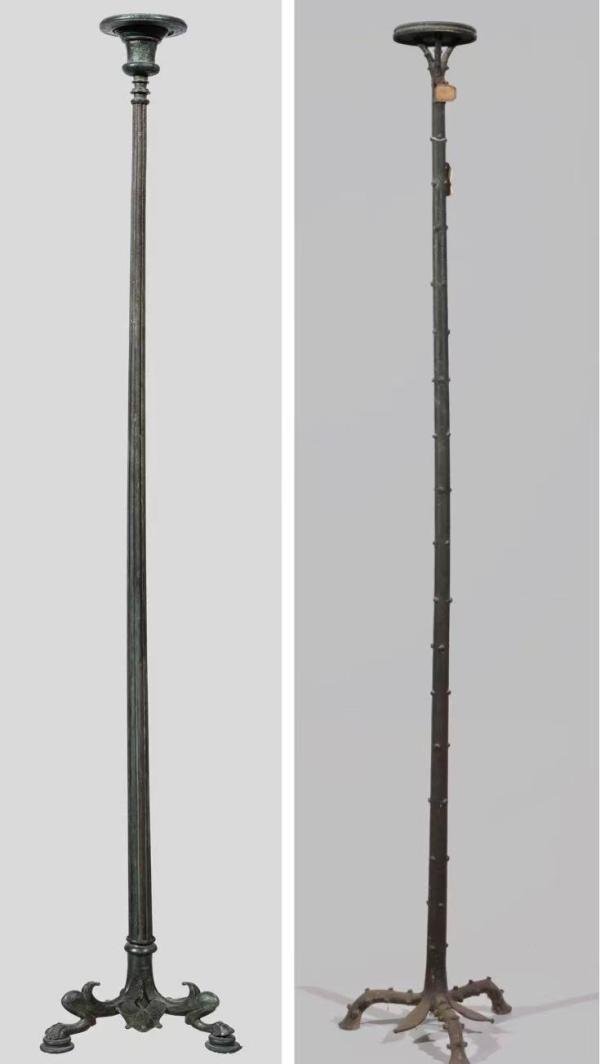

Many items presented in the exhibition correspond to the murals of the same period. It reflects the relationship between creation and life at that time. Particularly evident are the lampstands, which in Roman times were lamps made of various materials such as pottery, lead, glass and bronze, fueled by oil, which was placed in a chamber containing a wick. When the wick is saturated and burns slowly, it provides long-lasting light.

Menorah, Pompeii, bronze, 1st century

Menorah fresco, Herculaneum, painted fresco, 1st century

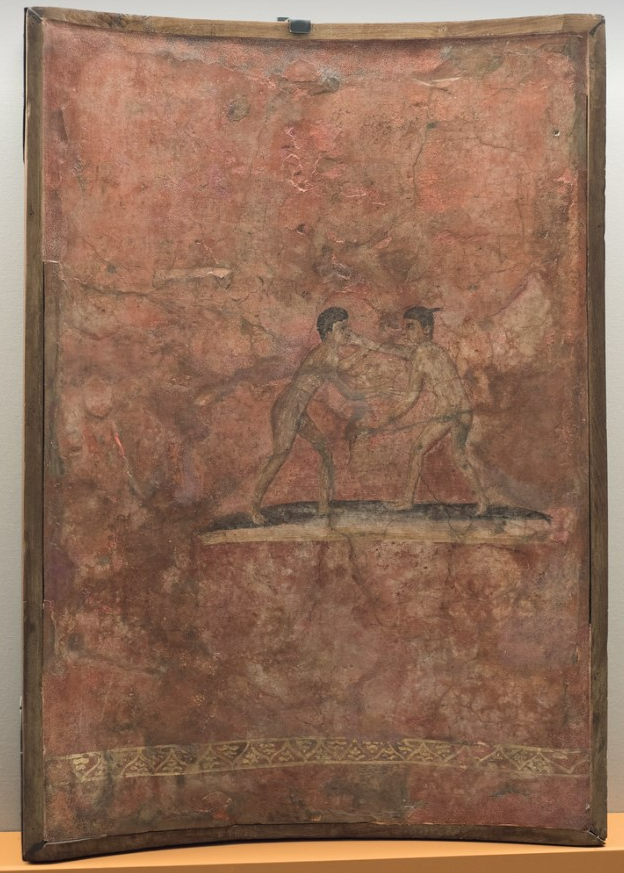

The life of the Pompeians in the 1st century AD is reflected in the "Fresco of Leaping Scene with Holding Weights", which depicts a square stone pillar with a bearded god (Hercules) engraved on the top, symbolizing the palm of victory Leaning on the stone pillar. At the same time, two athletes are holding weights in the long jump. They wear wrestling gloves on their hands during the long jump, which shows the sequential relationship between the long jump and the wrestling in the pentathlon.

Fresco of a jumping scene with holding weights, Pompeii, painted fresco, 1st century

The figure on the right concentrates on rubbing his body with oil before the game, showing the athlete's preparation process. Typical equipment for physical training included oil stored in vials, which wrestlers would anoint their bodies with before a match. In addition, there is a body scraper for degreasing at the end of the game. Together, they form the basic tools for physical activity preparation.

Arabella oil tank, Pompeii, bronze, 1st century

Body scraping board, Pompeii, bronze, 1st century

Frescoes also adorn the Roman baths, in one originally for the semicircular chamber of the thermal baths. Against a red background, two young wrestlers face off in a brown field on a yellow ground, depicted with only a few quick brush strokes. The frame of the picture was originally wrapped with a yellow tapestry pattern, but now only the lower part of the edge remains. On September 26, 1912, the National Archaeological Museum of Naples acquired the fresco, along with coins and other objects, for a low price of 500 lire.

Fresco with battle scene, Pompeii, painted fresco, 1st century

The depiction of women is also a new research point for murals. For a long time the study of the Roman Empire has been dominated by a focus on male displays of strength. Unlike the domestic space of many other societies, the Roman domestic space was not understood as a feminine space. In the exhibition, "Girls in a Boudoir" shows the scene of three women gathering and chatting in the porch next to the garden. The woman on the left is wrapped in a cloak and headscarf; the one in the middle leans against a pillar; the one on the right rests a water jug on her left arm and rests her right arm on her head.

Ladies in a boudoir, Herculaneum, painted fresco, 1st century BC-1st century AD

Scholars have also revealed how Roman women constructed a hierarchy with small differences in clothing through the study of women's clothing.

Men and women offering offerings, Stabia, painted fresco, 1st century

At the end of AD 79, Mount Vesuvius erupted and buried Pompeii, Herculaneum and the Gulf of Naples under volcanic ash overnight, along with all the way of life at that time. For the next thousand years, Pompeii was covered under volcanic ash more than six meters deep. Its name and location are forgotten. In 1599, the architect Domenico Fontana discovered an ancient wall with carvings when he opened up an underground aqueduct to divert water from the Sano River. In 1738, the ancient city of Herculaneum, which suffered the same fate as Pompeii, was excavated. In 1748, with the funding of the King and Queen of Naples, Pompeii was also rediscovered. However, they only excavated ancient art treasures to decorate their own. palace. Large-scale excavations and archaeological research on Pompeii did not really begin until the 19th century.

Necklace pendant with images of the gods, Herculaneum, painted fresco, 1st century

The frescoes became evidence of life at the time. Although the ancient Roman muralists may have painted purely from the perspective of their own trade, they left a material civilization, which is a glimpse of the past civilization in the present.

Note: The exhibition will last until April 9, 2023. The pictures in this article are provided by Pudong Art Museum, and the cultural relics are from the National Archaeological Museum of Naples