"Vittore Carpaccio: Master Storyteller of Renaissance Venice," currently on view at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., is the painter's first retrospective outside of Italy.

Vittore Carpaccio (c. 1460/1466–1525/1526) was a leading figure in Venetian Renaissance art, known for his large and spectacular narrative paintings that brought sacred history to life. The exhibition features some 45 paintings and 30 drawings, ranging from large-scale canvases painted for charitable societies to smaller works that originally adorned the homes of wealthy Venetians, and are surprisingly innovative. Particularly striking are two famous oil paintings from the Slavic St. George's Synagogue in Venice and the Reading of the Virgin from the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

At the exhibition site, Carpaccio's best works are all commissioned and created in a narrative way. The exhibition reunites all six paintings from the life cycle of the Virgin Mary.

American writer Henry James once said: "It is a bit absurd not to use 'he' as a refrain when talking about Venice." The time is 1882, and the American writer is not yet 40 years old. What James said "he It was Vittore Carpaccio, the early Renaissance painter whose narratives of saints adorned the floating city and its surrounding churches.

James fell in love with Venice, and he wrote an article about being so shocked he gasped in front of paintings by Tintoretto and Bellini. He found, however, that Carpaccio was "nearer to perfection" than Tintoretto, although he felt no need to dwell on this, "his reputation is louder today than ever," James wrote in 1882.

Carpaccio, Nativity of the Virgin, circa 1502/1503, oil on canvas, Academy of Carrara

But as the 20th century dawned, Venice’s pilgrims and sightseers were drawn to the passionate, stirring paintings of Titian, Tintoretto—and Tintoretto even featured “contemporary” artists at the recent Venice Biennale. Identity appears. The answer given by the curator is: he is very modern; he breaks the rules; he reminds young artists that they should also break the rules.

In contrast, Carpaccio's works of half a century earlier were more Gothic and more conservative. His name has faded into the modern mind, and he is one of the old masters who lost their celebrity status when the storm of modernism hit.

Therefore, the "Vittore Carpaccio Exhibition" at the National Gallery of Art in Washington tries to give the audience a full understanding of this perfectionist painter. This is the most important Carpaccio exhibition held outside Italy for the first time in 60 years. The exhibition brings together works on loan from nearly 50 museums, universities and churches.

Carpaccio, The Young Knight, 1510, oil on canvas, Thyssen Museum, Madrid

Luxurious, fantasy, solemn, magnificent in the prime of life, slightly slovenly in the old age. Carpaccio is not as moving as Bellini, far less intelligent than Titian, and less nervous than Tintoretto.

The National Gallery of Art in Washington features two of the nine fascinating paintings he created after 1500 for the Slavic Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni (also known as the Dalmatian Synagogue, founded in 1451). One of them is the panorama "St. George and the Dragon" (c. 1504-1507), in which the martyr's spear pierces the throat of the beast. Another is the wonderful Saint Augustine in his Study (c.1502), probably Carpaccio's most famous work. James called it "a pearl of emotion, the color of a jewel". The exhibition ranges from extremely detailed studies of saints' heads and soldiers' armor to quick sketches made of line.

Carpaccio, Madonna Reading with Child, circa 1496-1497, Samuel Courtauld Trust, Courtauld Gallery

Unlike many artists who immigrated to Venice, Carpaccio was born in the early 1360s, the son of a Venetian leather merchant. Whether he studied under Giovanni Bellini or his lesser-known brother Gentile Bellini is uncertain. By the early 1490s, however, he had begun to paint religious and domestic scenes, such as Two Women on a Balcony, on loan from the Museo Correr in Venice, which continued Bellini's breath, but also with Carpaccio's own style.

Carpaccio, Two Women on a Balcony, circa 1492/1494, oil on panel, Museum Correr, Venice

Women appearing in profile is a common choice for Capaccio. He likes static compositions, which make people feel timeless, even a bit medieval. They play with pet dogs, sit among exotic birds... the painter demonstrates his skill and attention to detail. They overlooked the green lagoon from their luxurious marble balconies. It is an imaginary space that Carpaccio lays out with rigorous perspective.

Carpaccio, Fishing and Birding on the Lagoon, circa 1492/1494, oil on panel, Getty Paul Museum

The excitable Victorian critic John Ruskin praised Two Women on a Balcony in one of his books as "the finest picture in the world". Seriously, it's not even Carpaccio's best work. Even more fascinating is his 1505 Reading of the Virgin. Maria in the painting has shed her usual blue dress for a lustrous vermilion gown. Recent conservation work reveals the incised left edge to be painted with a sun-bathed forearm covered in blue fabric and the toes of the Christ Child.

Carpaccio, The Reading of the Virgin, circa 1510, oil on panel turned to canvas, collection of Samuel H. Kress. Recent protection shows the baby's left white arm and toes.

Carpaccio's best works are written in narrative cycles—The Legend of Saint Ursula, The Life of the Virgin Mary, The Life of Saint Stephen—mostly inspired by the Venetian synagogue (Scuole Grandi of Venice, also known as "Brotherhood of Venice" is a broad term for the mutual aid religious groups formed in Venice. . The exhibition combines all six of the "Life of the Virgin Mary" (from Birth, Annunciation to Sleep). But most striking are the two monumental works from the Slavic St. George's Synagogue, expressing great care and containing marvelous detail in their visions of holy courage and knowledge.

Carpaccio, Saint George and the Dragon and Four Scenes from the Martyrdom of Saint George, 1516, oil on canvas, Monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore

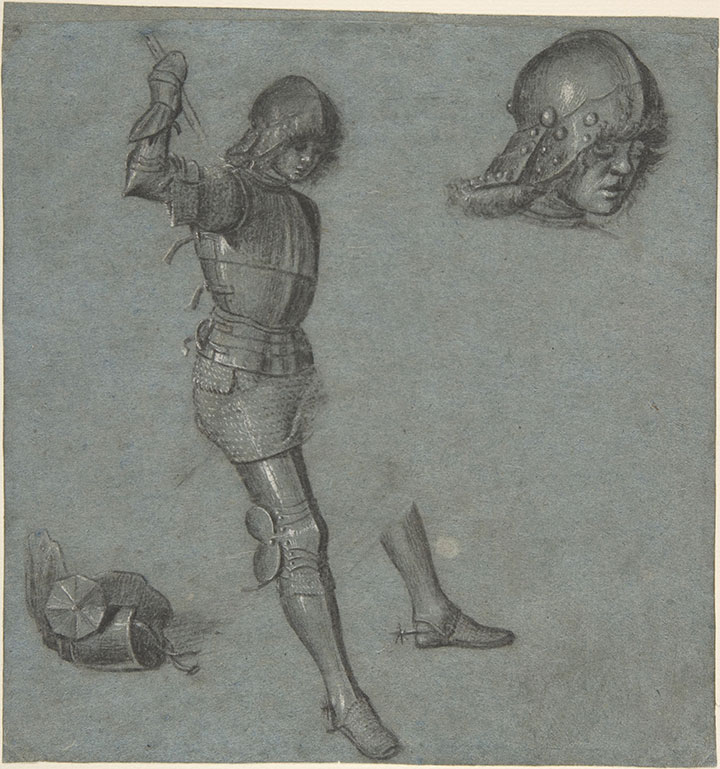

In "St. George and the Dragon," St. George charges forward on a prancing horse, but Carpaccio seems more interested in depicting the mutilated bodies on the ground that are becoming Delicacy for lizards and snakes. A beautiful work on paper, on loan from the Metropolitan Museum, shows the painter's study of plate armor, allowing the viewer to see the soft ripples of chain mail and the shimmer of greaves.

Carpaccio, Study of a Youth in Armor, circa 1500-1505, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In “St. Augustine in His Study,” Carpaccio’s genius for constructing imaginary spaces and seductive narratives reaches its zenith. Augustine (long mistaken for St. Jerome) sits at a table, drawn by a mysterious vision. His study is full of open books and sheet music.

The mitral hat and staff are nestled in niches in the background, echoing the architecture of the Slavic St. George's Synagogue. The supernatural light outside the window casts not only on Augustine, but also on a fluffy puppy lying on the floor next to a card with Carpaccio's name on it. Visiting the painting in Venice in 1882, Henry James wrote that it "combines the most exquisite finish with a general grandeur", but also complained that in St. Well, the caretakers are greedy and the tourists can't stand each other."

Carpaccio, St. Augustine in his Study, after about 1502, in the Slavic St. George's Synagogue, Venice

In the mid-1510s, as prosperous Venice descended into war, Carpaccio began to lose his grip on art, and his rigorous lines and meticulous studies gave way to a strange, even cartoonish, late style. The National Gallery of Art in Washington has an altarpiece depicting the martyrdom of Christians, their bodies wound bonelessly around trees (or crucified). Later on the Flight to Egypt or the Pietà looks almost amateurish, with unconvincing drapes and gaudy colours. It's as if the aging painter was trying to keep up with the times, like the younger Giorgione and Titian, but couldn't get the hang of painting.

Carpaccio, The Flight into Egypt, circa 1516/1518, National Gallery of Art, Washington

Perhaps when seeing Carpaccio (Carpaccio), many people will think of "thin-cut raw meat". Indeed, Carpaccio's legacy included painting and cooking. The dish was invented in 1963 at Harry's Bar in central Venice. Owner Giuseppe Cipriani named the new dish after a large Carpaccio exhibit that was on display at the time. Clearly, red inspired him. The bar has invented some interesting novelties, each named after the artist. Bellini, for example, is a sickeningly sweet drink made of prosecco mixed with white peach puree.

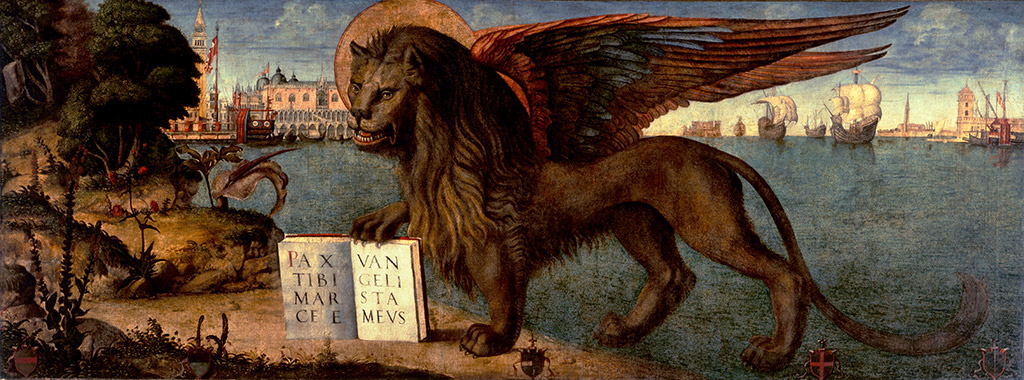

Carpaccio, The Lion of San Marco, 1516, oil on canvas, Ducal Palace, Venice

This exhibition will also be on tour at the Duke's Palace in Venice. The "Lion of St. Mark" in the exhibition comes from the Duke's Palace in Venice. St. Mark's is the symbol of the Republic of Venice. The palace itself and the bell tower of nearby Piazza San Marco can be seen in the background, with the Church of San Giorgio Maggiore and the Slavic Synagogue of St. George sitting by the water. Full of what James calls "the luxury of loving Italy".

The exhibition will run until February 12.