The eighteenth century was the century of enlightenment. The light of reason dispelled the fog of ignorance and illuminated the face of the South American continent.

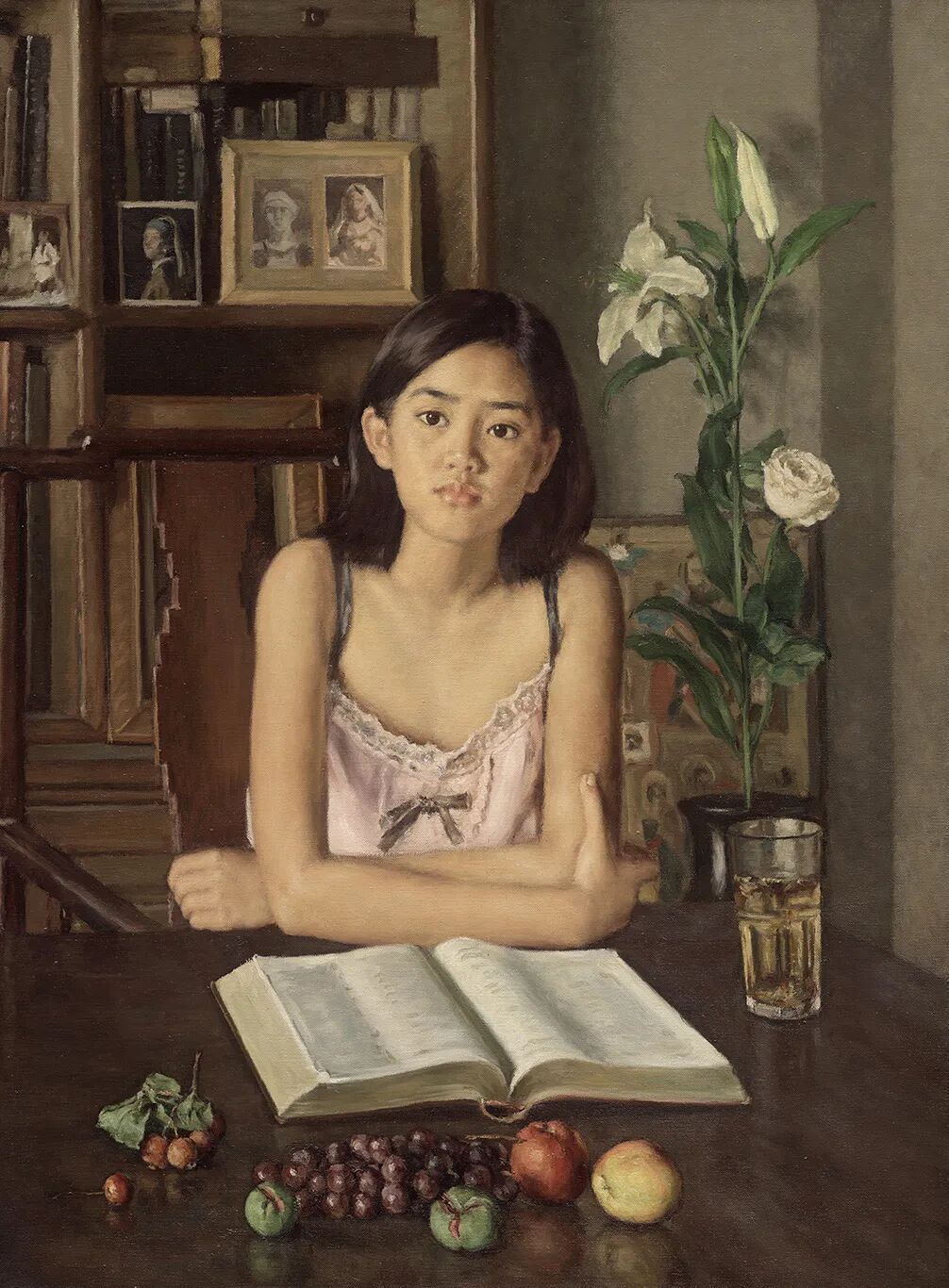

Latin America is a continent of mixed blood, where European, African and American cultures blend together, creating a dreamy, magnificent and grotesque "Mestizo World". At the time of the European Enlightenment in the 18th century, a "Latin American Art Enlightenment" quietly took place in Latin America.

Juan Rodríguez Juárez, De Mulato y Mestiza produce un Mulato Regreso-Atrás (De Mulato y Mestiza produce un Mulato Regreso-Atrás), 1715 , Museum of the Americas (Museo de America), Madrid, Spain

between order and liberation

On the west coast of the Atlantic Ocean, at one end of the southern hemisphere, Latin America is huge and vivid. Although starting from Europe at that time, this continent, which Marquez called "One Hundred Years of Solitude", is far away and untouchable, but it has never wandered outside civilization. , like a burning furnace, blends Spanish beliefs with local spirits, envelops African and Asian civilizations, and forms a unique "Mestizo" (Mestizo) soul in Latin America.

Miguel Cabrera, Spaniards and Muratos, Creation of Morisca, 1763, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Los Angeles, USA

Mestizo (Mestizo) means "mixed blood" in Spanish, derived from the Latin mix (Mixticius). Mixing and blending is the essence of Latin America and the essence of Latin American art. Latin America in the 18th century launched a journey of artistic enlightenment (La Ilustración) around the mestizo culture.

Miguel Cabrera, The Spaniard and the Indian Woman, Creating the Mestizo, 1763, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, USA

Since the arrival of Europeans in the 16th century, Latin America in the 18th century has experienced more than two hundred years of colonial rule, gradually forming a stable social system and structure. Europe and North America, which ended with the French Revolution and the American War of Independence in the 18th century, are already preparing for new changes in the 19th century. Social structural changes also came to the South American continent. Since the 19th century, Latin America started the War of Independence. In 1810, the flame was first ignited from Mexico and burned all the way south to Peru.

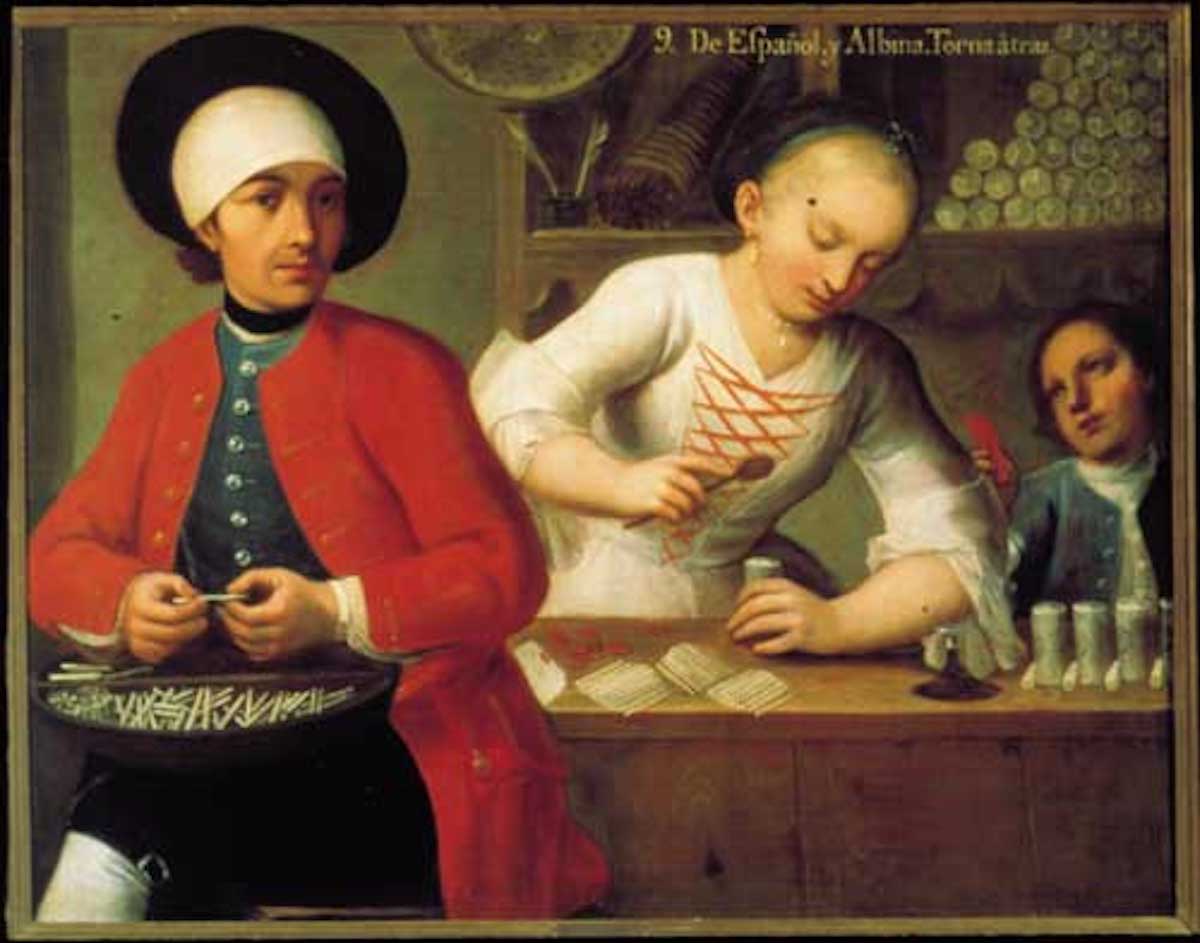

Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz, Spaniards and Albinos, Creation of Tornatrás (De español y albina, torna atrás), 1760, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, USA

Casta Painting, as a representative work of Latin American art enlightenment, was produced between centuries and lasted for a century. It is not only settled in the solid structure of colonial rule, but also anxious and eager to subvert changes, presenting a unique look. The vivid picture provides a space-time shuttle tunnel for us today to return to the distant era three hundred years ago.

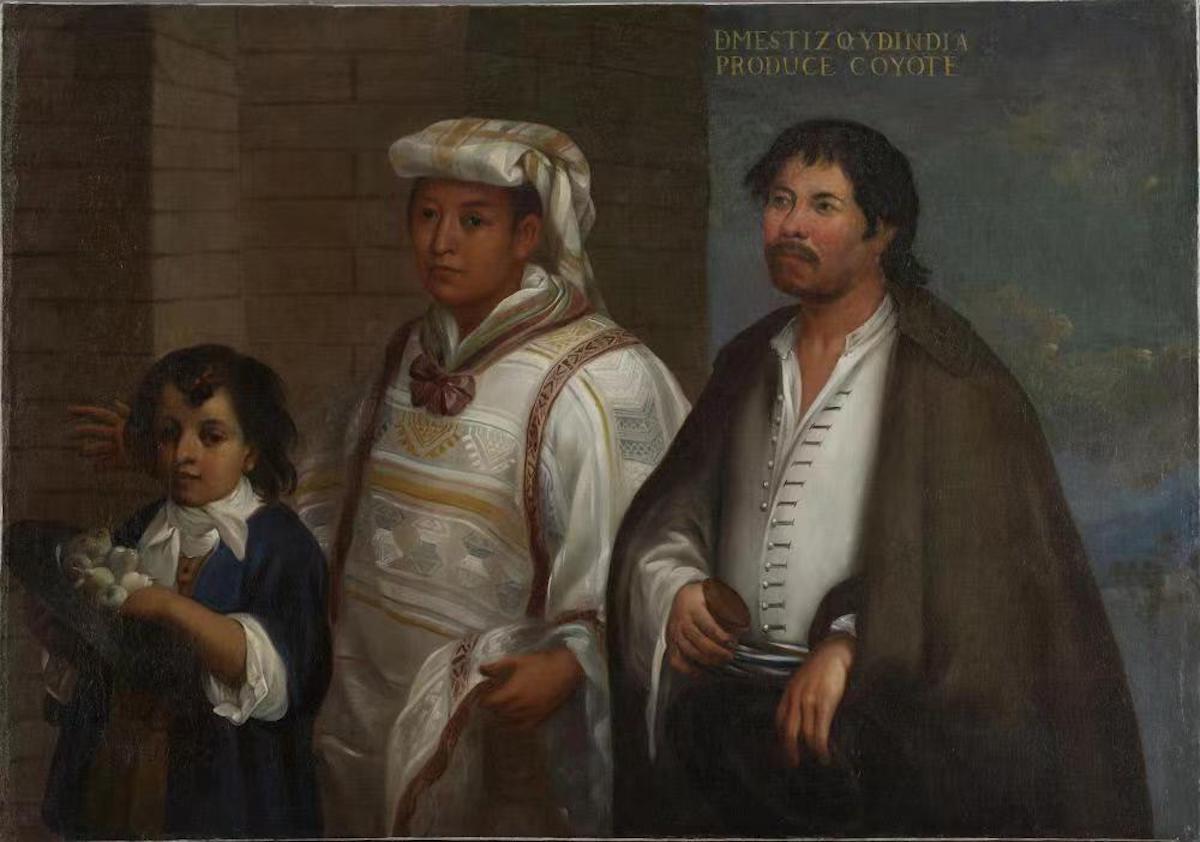

Juan Rodriguez Juárez, De mestizo, y de india produce coyote, 1715, Hispanic Society Museum of America), New York, USA

In the 16th century, Spain established governorships in the Americas. The Governorship of New Spain (Virreinato de Nueva España) with Mexico as its capital and the Governorship of Peru (Virreinato del Perú) with Lima as its capital were the two centers of the empire.

New Spain, with Mexico City as its capital, includes today's Mexico, Central America, and most of the western and southern United States; the Governorate of Peru covers most of the countries in South America today, extending to Chile and Argentina. As an important city-state in New Spain, Mexico City was built into a European-style city-state, and Latin American cities gradually took shape.

Cristóbal de Villalpando, View of the Plaza Mayor of Mexico city, 1695, Corsham Court Collection, England Wiltshire

Flipping through Mexican paintings of the 17th-18th centuries reveals secular paintings depicting cityscapes. "City Hall Landscape" presents the whole city square and municipal building, with various characters shuttling among them, and a European city is beginning to take shape on the land of Latin America. "Canal Boulevard" depicts the transportation system of Mexico City, and the communication of city residents is greatly enhanced.

Pedro Villegas, Paseo de la Viga, 1706, Museo Soumaya, Mexico City

The development of cities and transportation promoted the integration of races. People of different skin colors began to communicate and intermarry. The population of New Spain was diversified, leaving a large number of mixed races with mixed skin colors.

José Joaquín Magón, De Espanol y Negro, sale Mulato (De Espanol y Negro, sale Mulato), Museum of Spanish Anthropology (Museo de Antropología), 18th century, Madrid, Spain

In order to distinguish different races, a racist system called Casta was established by the Spaniards. This system classifies and names the population based on skin color and blood origin. Although this colonial system based on racism is under fire today, it unexpectedly gave birth to a distinctly Latin American style of art - Gusta oil paintings, which feature the theme of interracial marriages, usually white and colored. The combination of races and have mixed offspring.

Unknown author, Spaniard Husband with Native Peruvian Wife, and Mestizo Child, 1770, Peru

Gasta oil paintings have a large number of depictions of people of color. European portraits in the 18th century depicted white people, and colored people often appeared as servants, entourages, acrobats, etc. Gasta oil paintings subverted the viewers’ old-fashioned imagination of portraiture, and colored people became the protagonists and central figures. The position and proportion in the picture are comparable to that of white people.

The Marriage of Captain Martin de Loyola to Beatriz Ñusta (The Marriage of Captain Martin de Loyola to Beatriz Ñusta), 1675-1690, Collection of the Church of la Compañía de Jesús, Cusco, Peru

In Latin America, there are indigenous arts that specifically depict indigenous people of color, and in the "Cuzco School" (Cuzco), which is prevalent in Peru, there are portraits of Indian tribes. Gasta's oil paintings portrayed people of color more abundantly, entered the colorful scenes of urban life, walked into gardens, shops, restaurants, and participated in various industries, enriching the theme of Latin American secularism art.

Unknown artist, Mestizos and Spaniards gave birth to Mestizos, 1770, Peru

Why Gasta oil paintings became popular is still a mystery, but it reflects the awakening of national consciousness and identity construction in Latin America. Interestingly, the artists who created Gasta's oil paintings are also of mixed Mestizo origin. Art creation is also a reconstruction of self-identity, exploring the possibility of identity and existence within the harsh racist system of the 18th century.

Joseph de Paez, De Espanol y Albina produce Torna Atras (De Espanol y Albina produce Torna Atras), 1780s, Museum of Mexican History (museo de historia mexicana), Mexico

Usually, a Gasta artist will create a series of 16 paintings, each with a different story and scene, forming a chain series of works.

Gasta oil painting series in the Spanish American Museum Photo: EL PAÍS

In the creation center of Gasta's oil paintings, Mexico City, the capital of New Spain, there is a large collection of Gasta's oil paintings. Spain, as the former suzerain country, also collected many precious paintings. It is worth mentioning that because New Spain includes most of the land in the Midwest of the United States today, coupled with the strong strength of American art history research and collection, some of the most precious Gusta oil paintings are collected in art institutions in the United States, including Los Angeles County Museum of Fine Arts, Denver Museum of Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Austin Blanton Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum, New York, etc.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art exhibited 14 of Miguel Cabrera's 16 Gasta oil paintings, and most of Miguel Cabrera's works are in the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo: "Los Angeles Times"

Gasta oil paintings were also introduced to Peru, another major center of the Spanish colonial empire, but only one series of Gasta oil paintings in Peru has been preserved so far, and the style is slightly different from that of New Spain.

Peruvian Gasta theme oil painting series

pedigree of mathematics

Although Gasta's oil paintings have created a group of outstanding painters, most of the authors of Gasta's oil paintings are anonymous. The painters seem to invariably use the 16 paintings as the standard for Gasta's paintings, and the names of the paintings are also highly consistent, following the formula : "A certain race and a certain race produce a certain race", such as "De mestizo, y de india produce coyote" (De mestizo, y de india produce coyote). The naming follows the established formula. The 16 paintings are combinations of different races. It seems that mathematical addition and subtraction and the rules of arrangement and combination are used to classify races and bloodlines.

Unknown artist, Las castas, 18th century, Museo Nacional del Virreinato, Teposotelan, Mexico

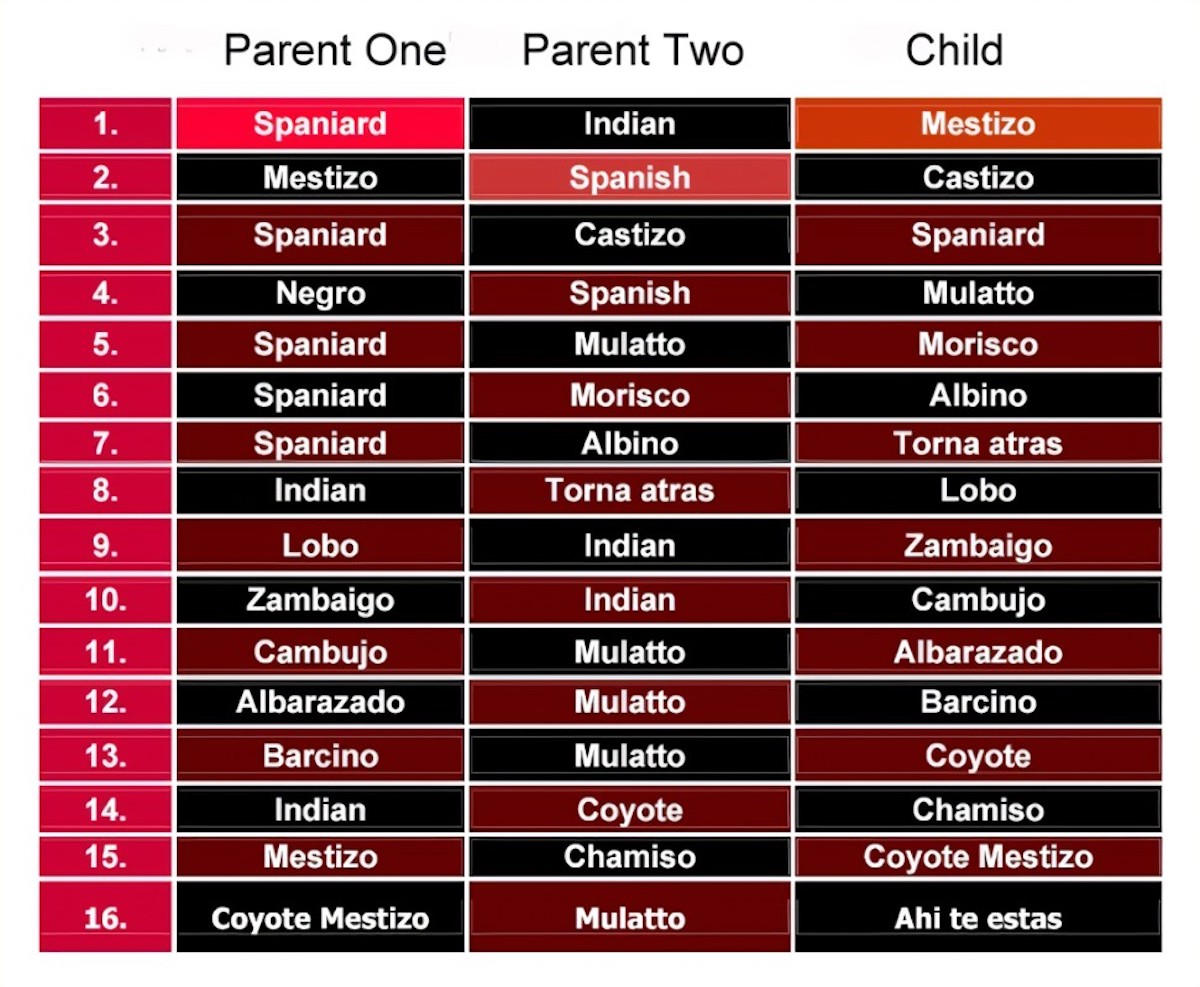

Casta is a word in the language of the Iberian Peninsula, meaning "blood". The English Caste also evolved from Casta, and later became a term to describe the Indian caste system. Casta in the Spanish colony is very similar to the caste system in India, both of which stratify races and form ranks.

Francisco Clapera, set of sixteen casta paintings, 1775, Denver Art Museum, Denver, USA

The Spaniards born in the Iberian Peninsula are the highest in the Gasta system, followed by the Spaniards born in the Spanish colonies, the American Indians are in the middle, and the African blacks are the lowest.

Gasta Atlas in the Museum of Mexican History (museo de historia mexicana) Image: infor7.mx

The main races intermarried to form secondary races, such as the Spanish-Indian mixed-blood Mestizo (Mestizo), the Spanish-black mixed-race Mulato (Mulato), and the Albino (Albino) ), Lobo, etc. There are 16 combinations of races to form a clear genealogy, which is also the naming code of the painting.

16 pedigree combination map Figure: martinharsh.com

Gasta's oil paintings are not only art, but also outline a social order for the colonists. Art is a visual illusion of order and structure. In the book "Imagination of Identity in New Spain: Race, Lineage, and the Colonial Body in Gasta's Oil Painting", Magali Carrera argues that Gasta's oil painting is actually the imagination of New Spain, and race is created, not natural.

The Joy of Sorting: Class, Fashion, and Order

Gasta's oil paintings differentiate and combine human beings to form a set of taxonomy. This difference caused by the distinction also brings a rich landscape of secular life, including class, occupation, lifestyle, and dress taste.

Installation view, “Painted Costumes: Fashion and Ritual in Colonial Latin America,” January 2023, Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, Texas, USA

The 18th century coincided with the period of Baroque art in New Spain. Baroque gardens often appeared in Gasta oil paintings and became leisure places for the aristocracy.

Artist unknown, De Albina y Español Produce Negro Tornatrás, 1770-1780, Banco Nacional de Mexico, Mexico City

The painting "The Abinos and the Spaniards Created the Negros" is centered on the fountain, with the protruding trail surrounded by a square, full of dynamics and drama, and people of all colors and races shuttle among them, reminiscent of the 16th-century Dutch painter Hieroni Mies Bosch's surreal painting "Earthly Paradise" is magical and full of imagination.

Juan Ruiz, De español y morisca, albino (De español y morisca, albino), 1760, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, USA

Walking in the garden is also the theme of Gasta's oil painting. The noble family enjoys the scenery and interacts with their children in the garden, showing the taste of life in New Spain. The scenery is quiet and beautiful, and it is integrated with the characters.

Joseph de Paz, De Español y Albina, Torn atras (De Español y Albina, Torn atras), 1780s, private collection, Mexico

Artist unknown, El Alvina y Espanol sale Negro Torna Atras (El Alvina y Espanol sale Negro Torna Atras), 1780s, private collection, Mexico

The artist not only described the life scenes of the leisure class, but also made a large number of detailed descriptions of their clothing and clothing. Therefore, Gasta's oil paintings are also a history of fashion in Latin America in the 18th century.

Miguel Cabrera, De español y morisca, albina (De español y morisca, albina), 1763, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, USA

In the works of Miguel Cabrera, we can see the painter's meticulous capture of clothing. The characters are dressed in high-quality velvet. The colors of lake blue, dark green or crimson red are bright and pure. Even though it has been more than 200 years since the creation, you can still feel the luster and smoothness of the velvet through the picture. The butterfly sleeves and lace edges reveal the A fashion trend in the Age of Enlightenment, striped shawls, silver jewelry, and Panama hats reflect the local taste of Mexico.

Miguel Cabrera, De español y albino, torna atrás (De español y albino, torna atrás), 1763, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, USA

Lace, weaving, embroidery, silk, patterns, handkerchiefs, neck scarves and other details all tell the lifestyle of nobles. Women like to wear hairpins and headdresses, and huge pearls show their status. The painter also brought Mexican decoration into his paintings, including crafts such as lacquerware, marquetry, and picture framing.

José de Bustos, DE ESPAÑOL E INDIA, PRODUCE MESTIZA, 1725

As a representative artist of Gasta oil painting, Miguel Cabrera is considered the most outstanding Gasta creator and was welcomed by Spanish rulers to create portraits for court women.

Miguel Cabrera, Doña María de la Luz Padilla y (Gómez de) Cervantes (Lady Maria), 1760, Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York, USA

"Lady Maria" is a portrait with a distinctive Baroque style. The whole picture is dominated by golden yellow and platinum, which is brilliant and dazzling. The golden embroidery on the skirt is particularly eye-catching. There is also black tear-stained makeup, showing the makeup fashion of Mexico in the 18th century.

José Joaquín Bermejo, Dona Mariana Belsunse y Salasar, 1780, Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York, USA

"Lady Mariana" created by Jose Bermejo for aristocratic women uses dark blue and silver-white as the theme, showing the stability and grandeur of the nobility, and also in line with the mature temperament of the protagonist's middle-aged woman.

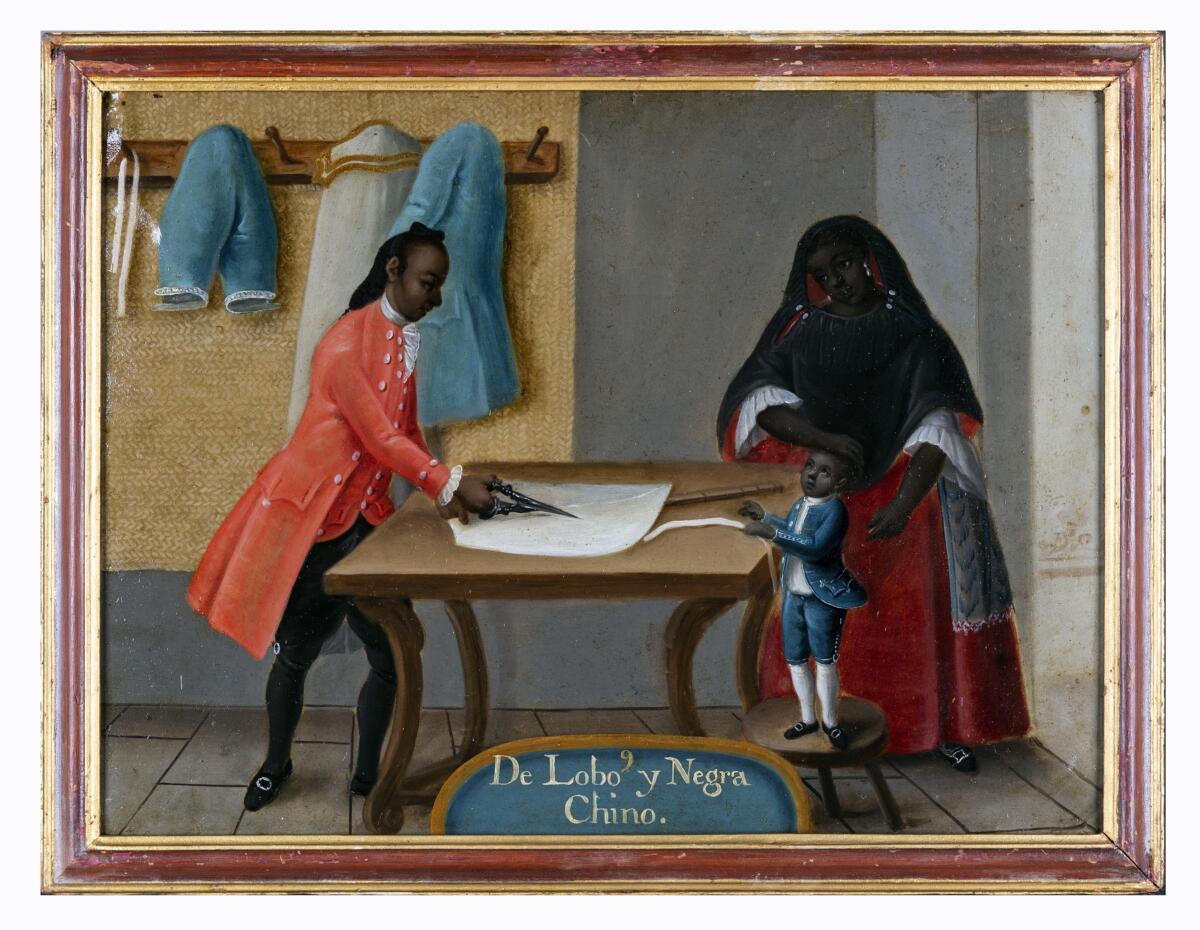

Andrés de Islas, De Lobo y negra chino, 1774, Museum of Spanish America, Madrid, Spain

Gasta painters also use space and actions to express the industries, occupations and economic status of different races and classes. Race is also often linked to economic status and social class.

José Joaquín Magón, Spaniards and Indians Create Mestizos, Born Humble, Quiet and Direct, 1770, Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico ,Mexico

The painter even defined the personality traits of the mestizo. When naming the work, the painter José Joaquin Magon described the mestizo as "born humble, quiet and direct". In the scene, a mixed-race child learns to read from a white teacher. The teacher and his mother are kind and friendly, and the picture is peaceful.

José Joaquin Magon, "The Creation of the Sambahiga Man by the Yndio and the Cambuja", 1770, National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico

In contrast to the richly dressed aristocrats were the colored people engaged in textile and clothing manufacturing. The aristocracy is the fashion consumer class, while the production end of textile production, design and tailoring is done by people of color.

Miguel Cabrera, De Mestizo e India, nace Lobo (De Mestizo e India, nace Lobo), 1763, Museum of Mexican History, Mexico

Gasta artists have depicted the production chain of the fashion industry very comprehensively, such as Mestizo people making shoes, Yndio people spinning cloth, and black people doing tailoring.

Artist unknown, Spaniards and Abinas, Creation of Tornatrás, 1760-70, private collection

These family workshop-style occupations are the skills that the whole family relies on to make a living. They are passed down from generation to generation, reflecting the development of urban handicrafts in early Latin America in the 18th century. The depiction of the fashion industry by the painter Gasta shows its social division of labor and reflects urban development. Diversity with the secular way of life of the citizens.

Francisco Crapella, De Chino e India, Genizara, 1775, Collection of Frederick and Jan Mayer ,Mexico

The kitchen is also the narrative space of Gasta's oil paintings, which is not only the basis of family harmony, but also the field of conflict.

Love and Hate in the Family: The Aesthetics of Violence

Most of Gasta's oil paintings depict a family of three as the theme, reflecting the importance of family and marriage in Latin America during the colonial era. However, it is quite puzzling that Gasta painters also chose "domestic violence" as the theme. A large number of oil paintings with "domestic violence" as the plot.

Andrés de Islas, De español y negra, nace mulata (De español y negra, nace mulata), 1774, Museum of Spanish America, Madrid, Spain

Scenes of domestic violence usually appear in families of people of color or interracial marriages, symbolizing interracial conflicts and reducing social violence to the smallest unit of the family.

José Joaquin Magon, De albarazado y salta atrá s, sale tente en el aire, 1770, National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico

Francisco Crapella, set of sixteen casta paintings, 1775, Denver Art Museum, Denver, USA

Domestic violence not only reflects disharmony within the family, but also reflects social disorder and system collapse. In Broken Borders, Lost Men, and Strong Women: Violence in Gasta Painting in 18th-Century New Spain, Evelina Guzauskyte argues that the theme of domestic violence reflects the broken borders of colonial society.

Francisco Crapella, De Mulato, y Española, Morisco (De Mulato, y Española, Morisco), 1775, Denver Art Museum, Denver, USA

It is worth noting that these violent scenes often take place in the kitchen. The background of the dispute is still lifes such as kitchen utensils, porcelain, tropical fruits, sugar cane, sauces, and turkey, which is a metaphor for the importance of food to human relationships.

Artist unknown, De negro y de india sale lobo (De negro y de india sale lobo), circa 1780

On the other hand, the painter also outlines his imagination of a model family through the brush. Breastfeeding, child rearing, parenting and family education are the subjects of many paintings.

Jose De Alcibar, DE ESPAÑÓL Y ALBINA NACE TORNA_ATRAS, DE ESPAÑÓL Y ALBINA NACE TORNA_ATRAS, 1778, private collection, Naples, Italy

Artist unknown, The Spaniards and the Alvinas, the Man Who Created Tornatrás (De Espanol Alvina Sale Tornatras)

The harmonious family theme painting is a moral education in the form of art, aiming at demonstrating how an orderly society should be and drawing moral models for racial harmony.

Juan Ruiz, The Spaniards and the Tornatrás, Creating the Tente en el aire, 1760, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, USA

Glory and Anxiety: Gasta in Art History

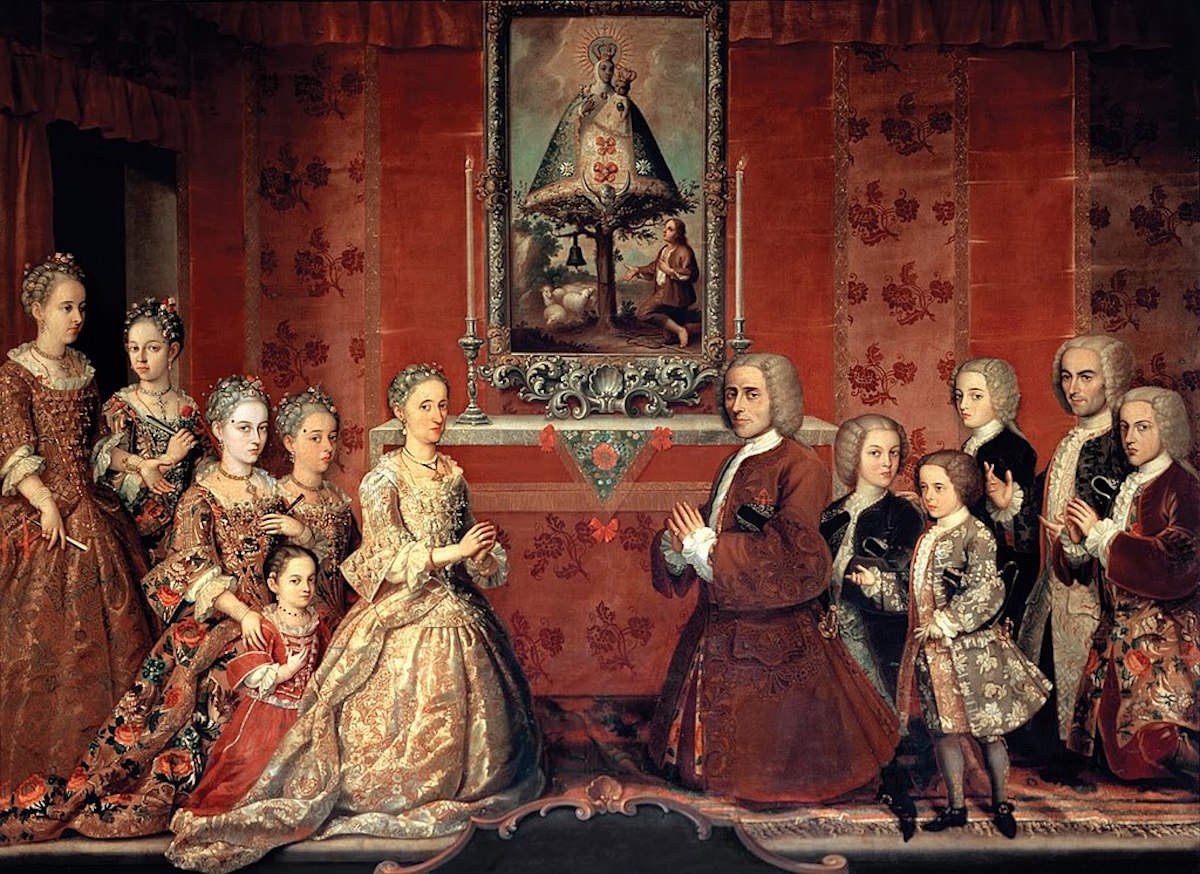

The 18th century, when Gasta was popular, was also the heyday of Baroque style. Although the Enlightenment movement aimed to get rid of the shackles of religion and move towards rationality, in Latin America, where the Catholic faith is deep, religion is still the theme of art, and the creation of Gasta's oil paintings also draws a lot of nutrients from religious paintings.

Jose de Alcibar, The Blessing of the Table, 18th century, National Museum of Art of Mexico, Mexico

Cusco School can be seen in Gasta oil paintings. The Cuzco school of painting prevailed in Peru from the 16th to the 18th century, featuring the depiction of Roman Catholic themes with bright colors, especially the ornate depiction of characters' costumes, which deeply influenced the way Gasta painters depicted costumes.

Unknown artist, Our Lady of Bethelem, 18th century, Cusco, Peru

Many Gasta painters are also famous for their religious paintings, such as Juan Ruiz, José Joaquin Magon, Miguel Cabrera, etc., their portraits in Gasta oil paintings The description method is exactly the same as its religious theme works.

Artist unknown, Retrato de familia Fagoga Arozqueta (Retrato de familia Fagoga Arozqueta), 1730

Looking at it today more than 200 years later, the religious works of these Gasta painters can be described as quite avant-garde, and they had already started the practice of surrealism as early as the 18th century. In Juan Ruiz's Catholic-themed paintings "The Heart of the Virgin" and "The Heart of Jesus", the heart pierced by a dagger glows in mid-air, resembling a small generator or a spaceship flying from outside the sky, fascinating the viewer. Get in touch with Dali, who is also a Spanish-language painter, and his surrealist works in the 20th century.

Juan Ruiz, The Heart of Mary, 1759, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico

Religious beliefs also appear in Gasta paintings, mixing secularism and religion in constructions. Luis de Mena hung the Virgin Mary in the center above the Casta screen, blessing every interracial family.

Luis de Mena, Virgin of Guadalupe and castas, 1750, Museum of the Americas, Madrid, Spain

The gorgeous costumes, racial hierarchy and order contained in Gasta's oil paintings symbolize the glory and glory of the Spanish colonial empire. But in the 19th century, Gasta oil painting began to decline. In 1810, the Latin American War of Independence first broke out in Mexico. Mexico abolished Gasta and regarded it as the ruling system of Spanish colonists.

José Agustín Arrieta, General's family portrait of Don Felipe Codallos, 1838, Somaya Museum, Mexico City

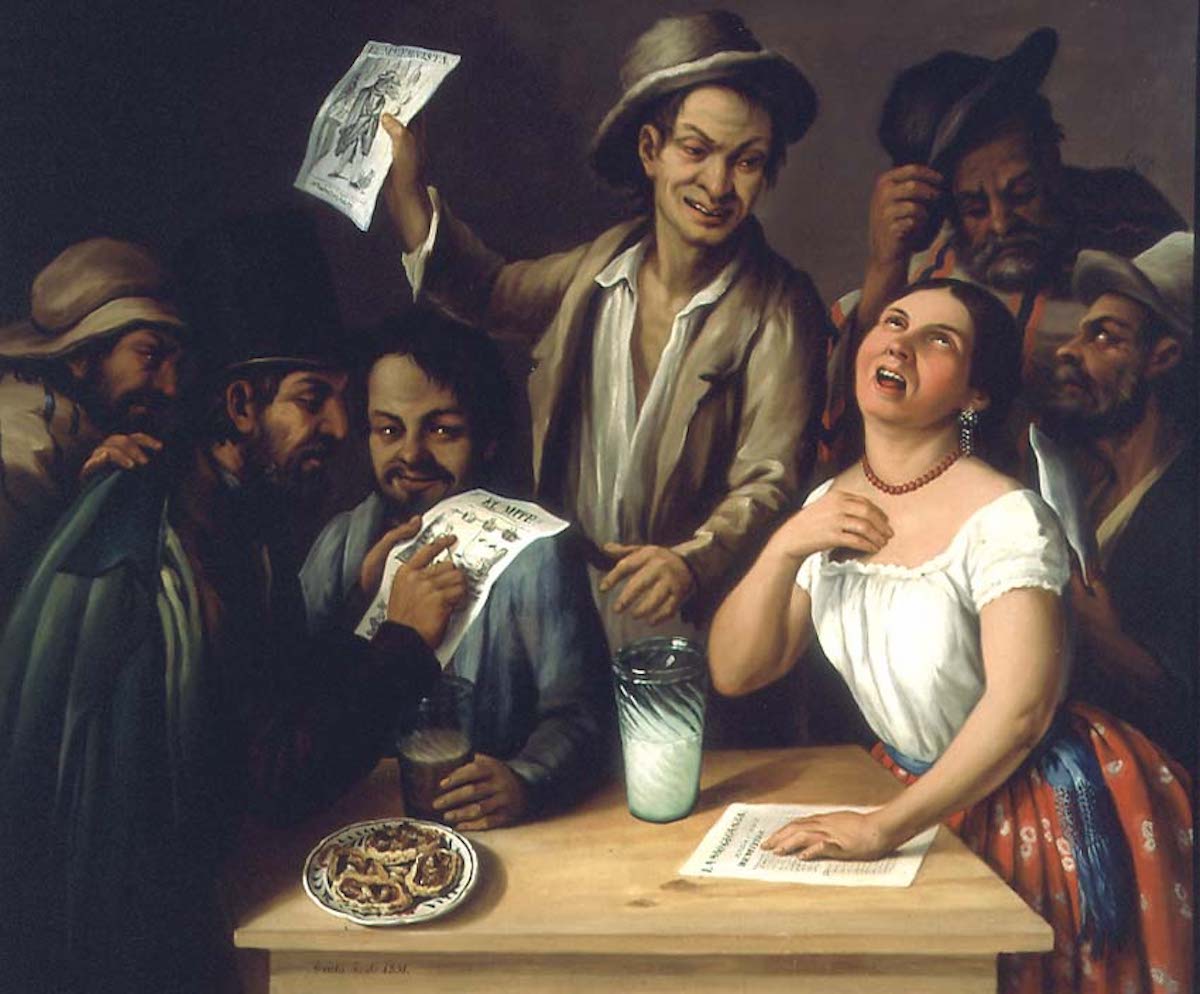

However, the abolition of Gasta cannot conceal the reality of a multiracial society. Paintings representing themes of multiracial society have not disappeared, but have evolved into a new form in the 19th century—costumbrismo, which combines realism and romanticism. Combined, it reflects the daily life and folk customs of Latin American diverse societies.

José Augustin Arrieta, Tertulia de pulquería (Party at the Tequila Bar), 1851, Museo Blaisten, Mexico

The works of Mannerist painters, especially José Augustin Arrieta, are the most representative. His works are full of interpersonal tension, full of tense atmosphere, and danger is imminent. In "Gathering at the Tequila Bar", white women are surrounded by men of color, and everyone loses their temper after drinking, revealing the essence of humanity.

José Augustin Arrieta, La Sorpreza (The Accident), 1850, National Museum of Mexican History, Mexico City

"Accident" depicts a street dispute that is about to break out. The woman with a blond hair seems to have a quarrel with a lady holding an umbrella. The man persuades the fight, and the colored people look out. Sitting on the street shows the higher economic and social status of the white people. Human races are more engaged in manual labor. Interestingly, between the conflicts between people, there are two dogs, one black and one white, fighting, which is a clever metaphor for the racial conflict between white people and people of color.

Felipe Santiago Gutiérrez, "La despedida del joven indio" (La despedida del joven indio), 1876, private collection, Mexico City

In the 19th century, due to the outbreak of the War of Independence in Mexico, the artistic career of local artists was interrupted, and the creation of multi-ethnic themes was often done by foreigners. German Karl Nebel was a European painter who traveled to Mexico. His "Images and Images in Mexico" Anthropological Journeys, a collection of illustrations documenting people of color in Mexico.

Carl Nebel, Indios de la Sierra Guachinango et Poblanas, illustration from the travel collection Pictorial and Anthropological Journeys in Mexico, 1836

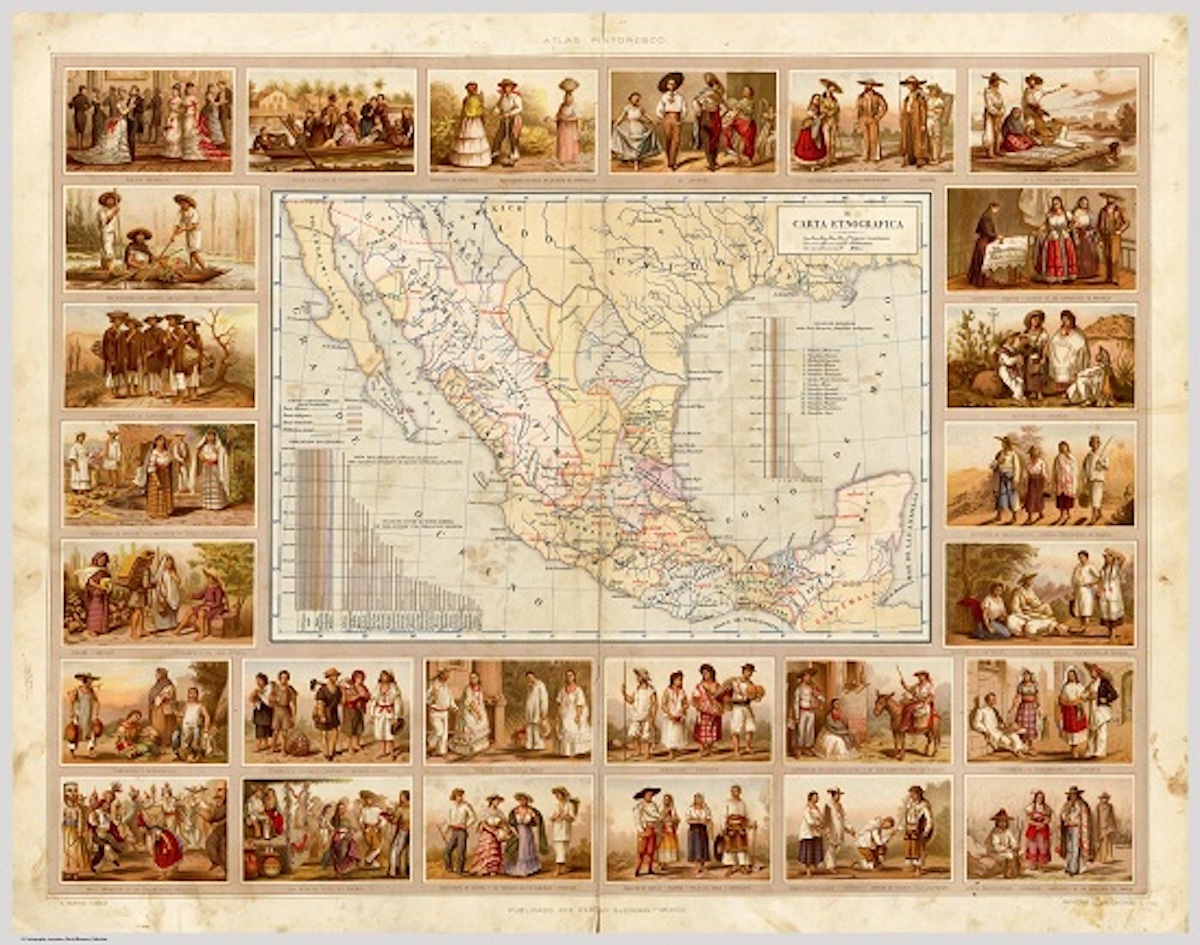

The former Gasta was gradually replaced by the Latin American nation (Raza). In the second half of the 19th century, the Mexican historian Antonio Cubaz depicted various ethnic groups in Mexico on his anthropological map. The form is very similar to that of Gasta oil painting, but the nature is different. At that time, Mexico got rid of France and restored the democracy of the Republic, and the painters who served in the finance department at that time carried out demographic statistics to consolidate the stability of the Republic.

Map and Anthropological Atlas of Mexico by Antonio García Cubas, circa 1868-1876, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Texas, USA

At the end of the 19th century, La Raza Cósmica (La Raza Cósmica), the foundational work of Mexican political thought, was published. Mixed races were put on the political agenda as a nation. A glimpse of Latin American art from the Age of Enlightenment.