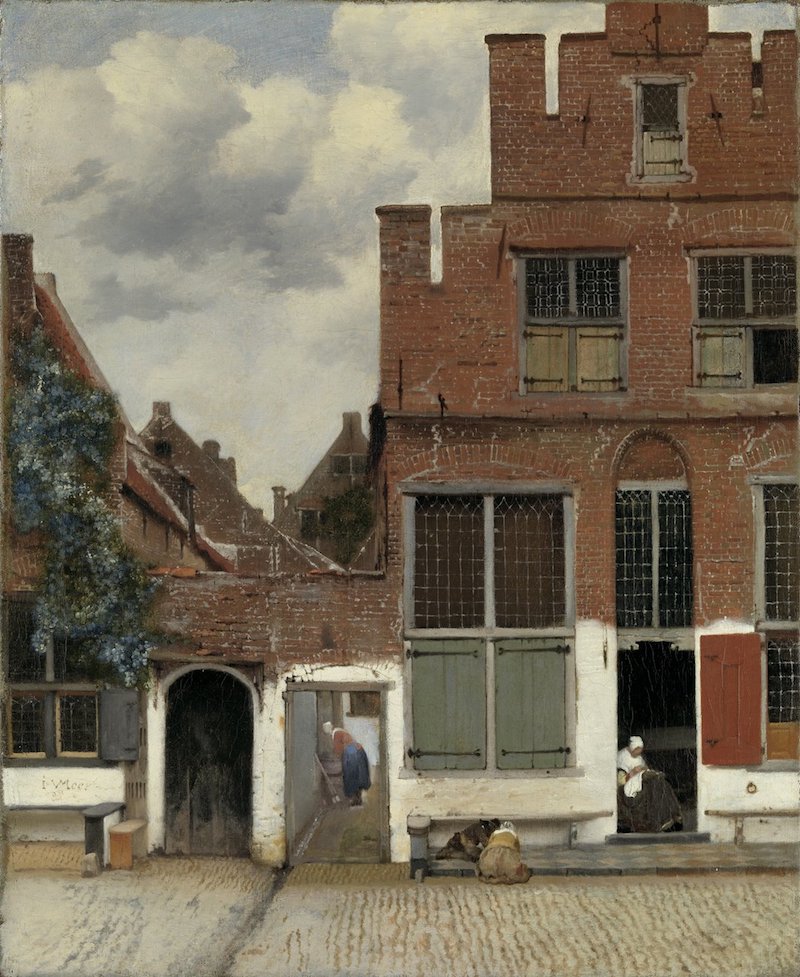

Washed cobblestone floors, white walls, gables of Dutch buildings, a woman sewing in a doorway. "Small Street" is the first work in the "Vermeer Exhibition" of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Every audience who walks through it will always be fascinated by the scene depicted in the painting.

It was a dramatic exhibition, with 28 Vermeers in ten dark rooms. Some works have a separate exhibition hall, while others appear in twos and threes. Viewers can watch longer, slower and sharper than ever before. However, Vermeer's paintings have their own mystery, their beauty and meaning are part of their content, the closer they are, the more alien they are, and yet the more serene.

Outside the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, a large Vermeer exhibition poster.

The "classic" has often stood the test of time, defied the skepticism of the fashion world, and displayed an irrefutable inner greatness. When we are shocked by the Venus de Milo, it is like traveling through a thousand years of history; we listen to Beethoven's Ninth Symphony and hold our breath, which is the same note played in Vienna in 1824.

Yet history screams back: It's not true! Most listeners in Beethoven's day hadn't heard Bach's notes, and he fell into obscurity for decades after his death in 1750. Similarly, people were indifferent to the saints described by El Greco, and deaf to the achievements of Kafka and Heston.

So, what is a masterpiece? Even if an agreement is reached at a certain stage of history, it may fall from the altar due to a change of taste.

Vermeer, The Little Street (House in Delft), circa 1658, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

There is perhaps no greater example of ups and downs in European painting than Vermeer. He lived in Delft all his life and was a minor celebrity there; yet two centuries after his death, his women who quietly read letters and poured milk attracted little attention again. When "Girl with a Pearl Earring" appeared at auction in 1881, its price was only two guilders. Today, Vermeer's works attract countless eyes as soon as they are exhibited. The light and tranquility in his paintings penetrate into the hearts of viewers.

Vermeer, Girl with a Pearl Earring, 1665, Mauritshuis, Netherlands

The largest ever Vermeer exhibition opened to the public on February 10 at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. It will almost certainly go down in history as Vermeer's most authoritative exhibition and cannot be reproduced. The museum's own collection, including the serene "The Milkmaid", the serene "Little Street", and more than three-quarters of the currently known works of Vermeer are gathered together. Only two days after the exhibition opened, the tickets for the exhibition were sold out. Vermeer let the impetuous modern man sink deep in front of his work, into his interior scenes, transforming the modulated paint into light in crystalline color and detail.

Exhibition view, "Girl with a Pearl Earring"

The exhibition is titled "Vermeer," and judging from its title, the exhibition is confident and modest. To only emphasize "rare" is to underestimate the show. The organization of the exhibition took seven years. It is already impossible to obtain such a valuable loan exhibition before 2020. The subsequent epidemic and the Russian-Ukrainian war have increased transportation costs and logistical coordination... Various preparations have presented this unprecedented situation. exhibition.

This is a near-perfect exhibition, perfect in argument, perfect in rhythm, as clear and pure as the light coming through a Delft window. In the empty exhibition hall, people can feel the attraction of the pearl-like gentle luster to the contemporary audience. Especially in the era of high-pixel reproduction, this attraction is even stronger. Why Vermeer and not other quiet painters of the 17th century Dutch Golden Age? Or, why us? What happened after Vermeer had been long forgotten that we are overwhelmed by Vermeer's silent woman?

Exhibition view, Letter Writer and Maid (1670), National Museum of Ireland, Dublin

One of the reasons for this is scarcity. Vermeer died young and had few works. The number of surviving paintings is about 37 (only 34 are confirmed, and the attribution of a few is uncertain), of which 28 are displayed in this exhibition. Eight works more than another full Vermeer retrospective at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., in 1995, when the harsh winter in Washington that year prompted hours of queuing.

Exhibition site, "Girl with a Flute" (left, about 1665-1675) and "Girl with a Red Hat" (about 1666-1667) from the National Gallery of Art in Washington. It is considered to be a companion product, but "Girl with the Flute" was removed from Vermeer's name last year.

In the Rijksmuseum, 28 works of various sizes are luxuriously displayed in 10 exhibition halls. Each work is surrounded by a semi-circular railing, allowing for close-up viewing as well as distracting crowds. Heavy velvet curtains were also hung between the works to block out the sound. Other than that, nothing but a few simple messages. There is no comparison of works, no videos, and even benches on both sides. The exhibition progresses slowly and silently. The seemingly empty exhibition hall is filled with details. It seems infinitely small, but it feels infinitely large.

The exhibition was designed by French architect Jean-Michel Wilmotte and curated by Pieter Roelofs and Greg JM Weber of the Rijksmuseum. Gregor JM Weber).

Vermeer, The Milkmaid, 1658-1659, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Several works are displayed separately in the exhibition hall, including "The Milkmaid" which is only 45 centimeters high. You can see Vermeer in all his power and poignancy in this little painting of a kitchen maid pouring milk for a bread pudding. In her rapt, focused gaze, on her austere bodice, every detail is held together by dots of hard, unblended paint. Everything from the nails on the kitchen wall to the little Delft blue tiles on the floor is a precise and perfect description of Dutch. Most importantly, in the light, Vermeer softens background and foreground with details that we anachronistically call "photography."

Vermeer's "The Milkmaid" (detail), on the bread, the paint dots are condensed together.

What is a masterpiece? In The Milkmaid, liquid comes to life, in the midst of the profane, touching the sacred. Even more touching than "Girl with a Pearl Earring." Girl with a Pearl Earring (on view only until March 30) occupies the most important position among Vermeer's five portraits. The silhouette of that turbaned girl is so perfect, the marvelous luster of that pearl, but two simple smears of white.

Vermeer's "Girl with a Pearl Earring" earring detail

Vermeer has a fascinating preoccupation with how things—letters, musical instruments, maps on the wall, Chinese porcelain, Turkish rugs, American beaver fur hats—make his women brilliantly described.

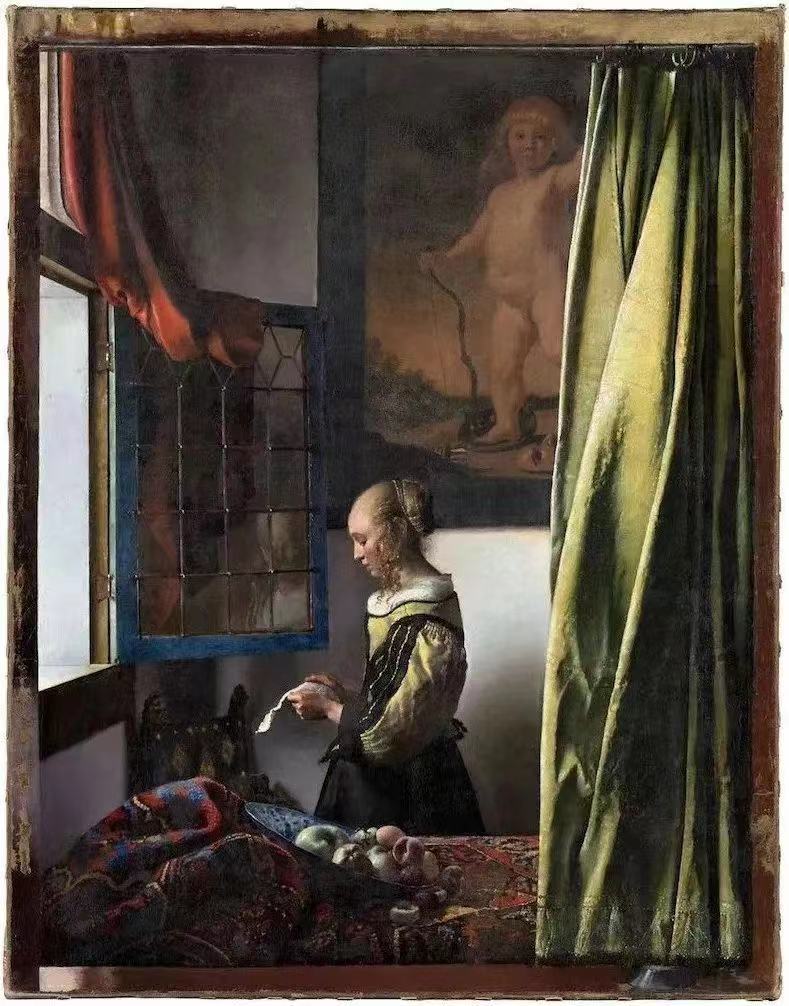

For example, the most important borrowed work in the exhibition, "Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window" from Dresden, is displayed in a separate exhibition hall for its extraordinary restoration. This is one of the typical scenes in Vimy's period. A young woman is standing sideways with her head slightly lowered. Her rapt reflection in the open window pane is unsettling and stirring. We also see the pilling of an Ottoman rug, the sheen of a Chinese fruit bowl, the drapes of a curtain. The back wall of the picture has been empty for over 250 years - but in 2021, thanks to the efforts of researchers and restorers, the smudged-out little Cupid appears, one of Vermeer's many paintings-in-pictures . It now appears that the woman in the painting is reading a love letter. The painting itself is also a love letter.

Vermeer, "Girl Reading a Letter at the Window", 1657-1658, Gallery of Old Masters, Dresden Collection, Germany

The same cupid appears in the background of two other paintings in the exhibition (plus the unloaned one, Vermeer has four works featuring cupids). Vermeer was an inventor and creator whose keen visual descriptive power even obscured how he deliberately constructed silent scenes. Unfortunately, Art of Painting from the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna did not arrive, nor did some works from the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Louvre in Paris and the British Atelier in Amsterdam. Another absentee is “The Concert,” a work that has not been seen since it was stolen from Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 1990.

Installation view, Mistress and Maid (1664-1667), The Frick Collection, New York.

Fortunately, the Frick Collection in New York has three Vermeers on loan for renovations, leaving New York for the first time in a century. The Frick Collection's "Mistress and Maid" is an extraordinary work, showing the mistress in a yellow jacket trimmed with white fur, receiving a love letter in the morning light; Young Woman With a Lute, Washington's Lady Writing, Berlin's Woman With a Pearl Necklace, and Rijksmuseum's Love Letter The women in (Love Letter) all wear the same yellow and white coat.

Women in multiple works by Vermeer, wearing the same yellow and white coat

The exhibition at the Rijksmuseum also includes two scholarly publications. The curators suggest that Vermeer, who had converted to his wife's Catholic faith, was a more Catholic artist than is commonly understood—at a time when the Netherlands was Protestant. Research speculates that the Jesuits taught Vermeer about the camera obscura, and the images it projects may have helped him sharpen and blur his gradient focus.

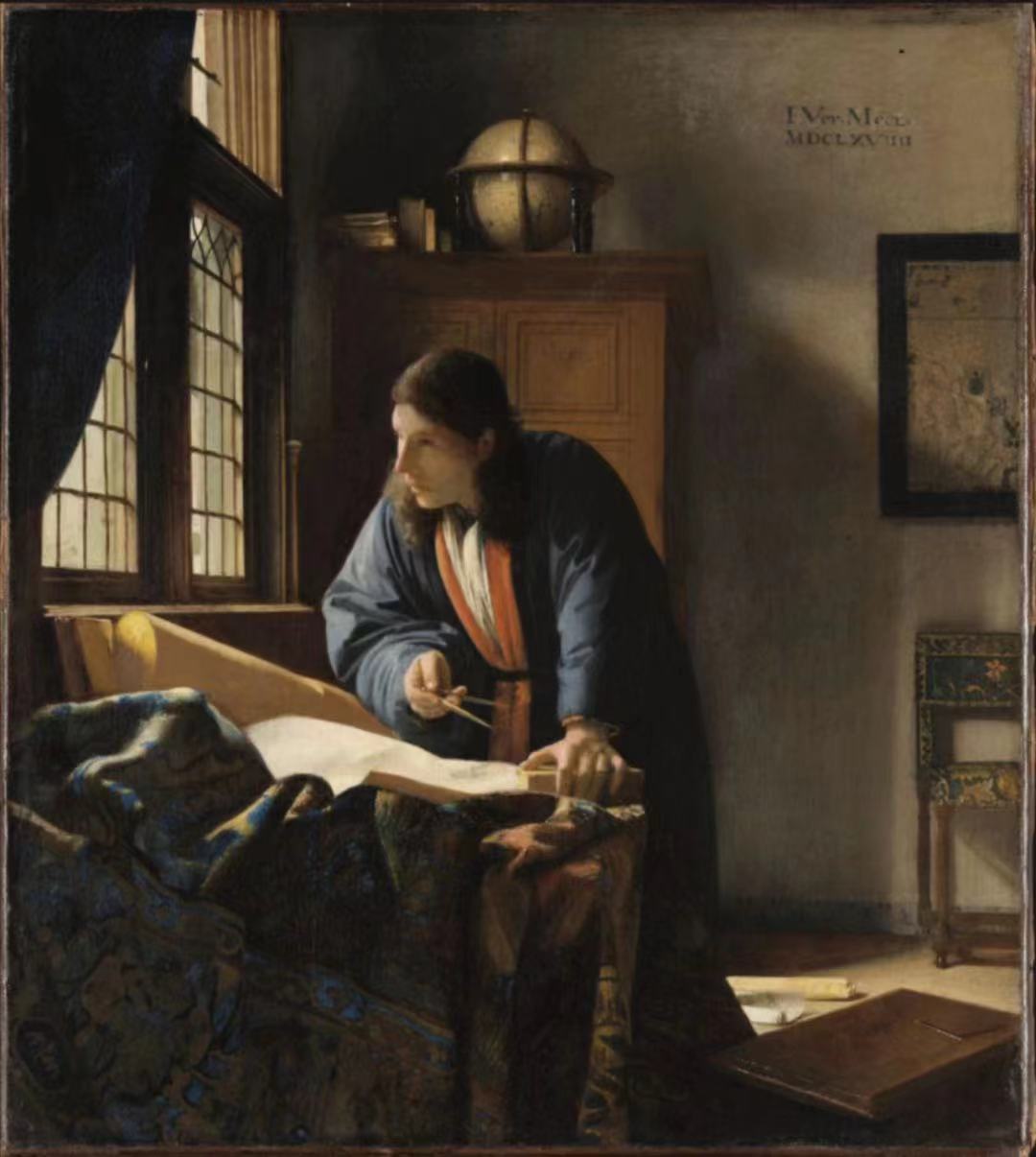

Vermeer, The Geographer, 1668/1669, Städel Kunstmuseum, Germany

Vermeer's "The Geographer" (detail), when new scientific instruments entered Vermeer's work.

They also delved into every item in the inventory of family possessions compiled after Vermeer's death. Here you can spy his "upholstered chair" in "The Geographer," the "wicker basket" for laundry on the floor in "Love Letters," and his wife Katharina's "yellow satin cape trimmed with white fur." We've learned that the white fur that fringes that iconic coat may not be actual mink, but relatively inexpensive rabbit or cat fur. That pair of pearl earrings is probably made of glass.

Vermeer, Love Letters (detail), 1669-1670, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

When rediscovered in the mid-19th century, Vermeer was more than just a neglected master. He seemed to be speaking to a Europe enamored with modernism—not least because of the optical techniques and unorthodox composition of his paintings, which audiences then, and even now, find his work to be as “real” as photographs.

In the alienated 20th century, this false innocence became increasingly fascinating, focusing on the transparency, the harmony of order that Vermeer sought. But beauty and tranquility are not enough to explain people's enthusiasm for Vermeer today, or the current focus on the slow time created by Vermeer. And the difference between actual feel and structure that manifests itself over time.

Mistress and Maid (detail) from the Frick Collection, New York

Quietly watching the girl pursing her lips, reading the letter under the dim light. Still, overcast view of Delft. The maid is engrossed in the milk being poured from the clay jug. Nothing important seemed to happen, but now it seemed precious.

Vermeer, View of Delft, 1660-1661, Mauritshuis, The Hague; Vermeer depicts his hometown.

Vermeer is a focus in the moment, proving that we are not yet completely engulfed in electronic data. We need to slow down time. Think again in 2023, what is a masterpiece? In this noisy world, they exude serenity and majesty.

The exhibition will run until June 4th