Professor Craig Clunas, Emeritus Professor of the Department of Art History at Oxford University, Honorary Fellow of Trinity College, and Fellow of the British Academy, was invited by Jiazuo Bookstore not long ago to hold an online lecture entitled "Royal Images of the Ming Dynasty".

In the long river of history, the loss of materials is the norm, while the preserved parts are coincidental and accidental. In the field of art history, what "known" and "unknown" historical materials exist? Professor Coruger discusses the royal images of the Ming Dynasty. Professor Yin Jinan, professor of the Central Academy of Fine Arts and director of the Advanced Institute of Image and History of the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, also participated in the lecture as a panelist. This article was compiled by Chen Xiangming, a doctoral candidate at Oxford University, and published by The Paper (www.thepaper.cn) with the authorization of the sponsor.

Professor Craig Clunas

Starting with the tendency of positivism in the field of art history, Professor Ke pointed out that the study of art history is often constrained by existing objects, and rarely involves a large number of lost artifacts and images. To paraphrase the famous words of former US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, there are also "known knowns" and "known unknowns" in the field of art history. The former is the main object of current art history research, while the latter is Because the physical materials have long been lost or there are only a few remains, there is an inevitable gap in our research and cognition. On this basis, Professor Ke further pointed out that there are still "unknown unknowns" in the field of art history research, that is, those materials that not only do not have physical objects, but also have no written records or other evidence that they have existed, so that we are not even aware of them. It used to exist, not to mention the current gap in cognition. Paradoxically, these "unknowns" in art history are often the crux of many problems.

In the study of royal images in the Ming Dynasty, these complex issues surrounding the "known" and "unknown" of materials also affect our understanding of the content and boundaries of Ming court art. The content of Professor Ke's lecture also gradually unfolded along this clue.

The first example of the lecture is "the known unknown" : According to the record in Volume 31 of "Records of Emperor Taizu Gao", on April 8th of the first year of Hongwu (summer 1368), Ming Taizu Zhu Yuanzhang ordered the painter to create a A series of paintings describing ancient filial piety and their own achievements in battle (picture 1) , so that the descendants who grew up in the deep palace can "know the difficulties accumulated by the ancestors", and these images do not have any physical objects left, their appearance, form and author Waiting for the information to be unknown. Although written sources can fill in some gaps, their credibility is also questionable. Ming Taizu's "Shilu" was only compiled during the period of Emperor Jianwen Zhu Yunwen, and it was overhauled twice after Yongle Emperor Zhu Di usurped the throne. Therefore, the written content describing these lost paintings must have been as long as the summer of 1368 at the earliest. It took half a century in 1418 to really take shape. In written and historical materials, the image of Taizu who was born in poverty and had a hard time starting a business, and his worries about the embarrassing task of raising future generations in the deep palace, all fit well with Zhu Di's ruling style. Written historical materials have a strong effect of "authenticity", but Professor Ke reminds us that they may contain more information about the period when the historical materials were compiled than the period described by the historical materials. This critical attitude towards historical materials also runs through the entire lecture.

Fig. 1 Axis of Shang Xi's "Picture of Capturing General Guan Yu"

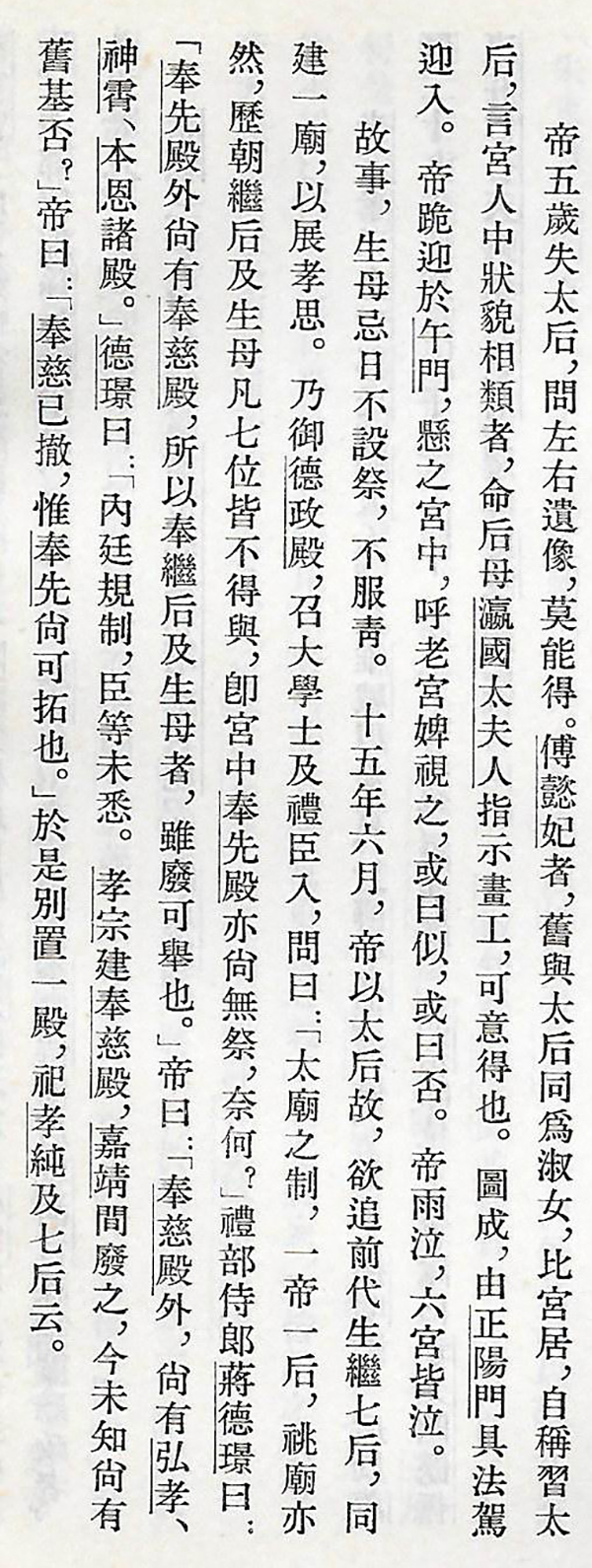

Another "known unknown" occurred in the late Ming Dynasty, and this example further clarified the complex relationship between written historical materials and visual historical materials. "History of the Ming Dynasty" records such a story about Emperor Chongzhen Zhu Youjian (renamed Emperor Zhuang Lie in the Qing Dynasty) repainting the portrait of his biological mother Xiaochun Empress Dowager Liu (Figure 2) : "The emperor lost the empress dowager at the age of five. Can get it. Those who passed on Concubine Yi used to be the same ladies as the Queen Mother, lived in the palace, and claimed to be the Queen Mother Xi. Among the people in the palace, those who have similar appearance, ordered the stepmother, Mrs. Ying Guotai, to instruct the painter. It is a pleasure to get it. The picture is made by Zhengyang Gate is equipped with a law to welcome you in. The emperor kneels at the Meridian Gate, hangs in the palace, and asks the servants of the old palace to look at him, or say yes, or say no. The emperor weeps, and all the six palaces weep." In this historical material Contains a wealth of information about court paintings in the late Ming Dynasty. For example, this portrait was brought into the palace after it was completed by painters outside the court. Does this imply that the court at the end of the Ming Dynasty no longer had court painters who directly served the royal family? For another example, this portrait was hung in the palace as a memorial, rather than prepared for various ancestral temple sacrifices, which seems to broaden our understanding of the function and meaning of ancestor portraits. These rich details together constitute the "authenticity" of historical materials, but "authenticity" is not equal to "historical facts".

Figure 2 "History of the Ming Dynasty", 12, Volume 114, Page 3540-2: Empress Dowager II Xiaochun Empress Dowager Liu

The compilation of "History of Ming Dynasty" itself referred to all kinds of old things collected by mouth in the early Qing Dynasty about the courts of the previous dynasty. By 1736, when the "History of Ming Dynasty" was revised, I am afraid that all the previous courts who retained first-hand memories of court life in the Ming Dynasty The old people are no longer alive, so the veracity of these rumors is even more untestable. These rich details in historical materials are like the detailed descriptions of food and clothing in Shiqing novels. They add to the credibility of the things described, but they do not necessarily mean that the various details described in the text are true reproductions of reality. Just as the image of Ming Taizu Zhu Yuanzhang in the previous example may better reflect the ruling ideology of Zhu Di Dynasty, in this material in "History of the Ming Dynasty", the last emperor wept like a portrait of his biological mother Under the rain, this tragic atmosphere also seems to imply the inevitable fall of the dynasty, with a meaning that future generations will examine the history of the previous dynasty. However, unlike Zhu Yuanzhang’s filial deeds map, which did not leave any image evidence at all, the complexity of this example lies in the preservation of relevant image historical materials. The authenticity and whereabouts of the portraits described in "History of the Ming Dynasty" are impossible to test, but the image of Empress Xiaochun still has image remains, which are preserved in the album "Bust of the Empress of the Ming Dynasty" collected by the National Palace Museum in Taipei. (image 3)

Figure 3 Empress Xiaochun (left) "Bust Portrait of the Empress of the Ming Dynasty" Volume 2

"Busts of Emperors and Empresses of the Ming Dynasty" is divided into two volumes, the first volume has 18 pages (eight emperors and ten empresses), and the second volume has fifteen pages (five emperors and ten empresses). It is the only existing court image depicting the appearance of Ming emperors and empresses. There are also full-length portraits of the emperors of the Ming Dynasty preserved in a series of life-size hanging scrolls (to be discussed later), but it is difficult to find traces of the female figures in the harem of the Ming Dynasty elsewhere; and the images in the album are exquisitely crafted and rich in detail, so It is also widely circulated, and is used as a reference for clothing by film and television works such as "Da Ming Feng Hua" depicting the court life of the Ming Dynasty.

However, Professor Ke's analysis of this work continues his critical attitude of viewing written historical materials as "historical materials" rather than "historical facts". Compared with text, the richness, intuition and details of images are more likely to create an illusion of "authenticity", but we must first clarify the historical background in which images were constructed and shaped as "historical materials" before we can evaluate the extent of the content depicted in images. to what extent, how much authenticity there is, and exactly what age information they provide.

Professor Ke started with the image details of "Bust of the Empress of the Ming Emperor", and compared other image materials horizontally, revealing that the content and form of the existing albums were produced in different periods of the Ming Dynasty, and after several interventions by various dynasties, even Finally, it was the result of mounting and molding in the early Qing Dynasty. While we can't give definitive answers to questions about the album's age, production, and audience, the images contain a wealth of clues that help us narrow them down. The posthumous title and temple title on the portrait can be used to determine the upper limit of the time when the image was produced. For example, the portrait marked with the words "Empress Xiaochun" can only be produced after Emperor Chongzhen ascended the throne in 1628, because Liu's family background was low, and in 1615 When she died in 2009, she had already been neglected, and she was posthumously named empress dowager when Zhu Youjian ascended the throne. He passed away in 1628 and was conferred the temple title and posthumous title by Emperor Chongzhen who ascended the throne in the same year. At the same time, since the concubines of Xi Zong and Emperor Chongzhen and his concubines were not included in the Bust of the Empress of the Ming Dynasty, these two The portraits established after 1628 are also the latest works in the two albums, which can help roughly delineate the lower limit of the establishment time of the contents of the album. In addition to the temple name and posthumous title, other inscriptions on the portrait also provide clues to the time. For example, the inscription on Xi Zong's portrait still calls him the emperor of "Da Ming", implying that the painting time of this portrait should be earlier than 1644, when the dynasty changed Before. On the other hand, the inscriptions next to the portrait of Ming Taizu Zhu Yuanzhang and Ming Emperor Jiajing are "Taizu Gao" and "Sejong Su" respectively (pictures 4 and 5) , without the " The two characters "Daming", and these two portraits are the front pages of the first and second volumes of "Bust of the Empress of the Emperor of the Ming Dynasty" respectively, while the word "Yu Rong" only appears on the portraits of Emperor Xiaozong Hongzhi of the Ming Dynasty and Emperor Wuzong Zhengde of the Ming Dynasty. . The discrepancies in these inscriptions point to an explanation that the images in the album were not all made at the same time, but are likely from different periods and sources. Small differences in the size of the individual images also point to this explanation. At the same time, the portraits in the first volume are all on silk, while the second volume is all on paper. The huge difference in materials can almost confirm that the images in the first and second volumes were not produced as a whole project at the same time.

Figure 4 Emperor Taizu Gao's "Bust Portrait of the Empress of the Ming Dynasty" Volume 1

Figure 5 (right) Emperor Sejongsu's "Bust of the Empress of the Ming Dynasty" Volume II

Once the approximate temporal range of the Bust of the Empress of the Ming Dynasty is determined, and the basic conclusion that the images collected in it were not produced at the same time as a whole, a more detailed analysis can infer that the contents of the album are in the What has changed over time. Among them, many contents included and omitted in the first volume are closely related to the reform of the ritual system in the early Jiajing period. Wu Zong had no heir, so the throne was passed on to his cousin Zhu Houcong, who was originally the son of King Xingxian, who became Emperor Jiajing after he ascended the throne. Emperor Jiajing wanted to fight for patriarchal status for his biological parents, but the ministers in the court insisted that Emperor Jiajing entered the Dazong with the Xiaozong, and should respect Wuzong's father Xiaozong as his father and his own father as his uncle. The so-called Daliyi in history was a three-year (1521-1524) long political struggle around this contradiction. This struggle ultimately ended in the victory of Emperor Jiajing, and the images in the Bust of the Empress of the Ming Dynasty reflect this. Emperor Jiajing's grandmother, Shao Shi, passed away in 1522, less than a year after he ascended the throne, and was posthumously named Empress Xiaohui, and she was also included in the painting with her old face in the first volume of "Bust of the Empress of the Ming Dynasty", And it was ranked in a relatively high position; while Xiaozong's mother and Wuzong's grandmother, Ji, was posthumously named Empress Xiaomu after Emperor Xiaozong Hongzhi ascended the throne, but she was the only birth mother of the Ming emperor who did not enter the album. These anomalies in "Bust of the Empress of the Ming Dynasty" further confirm that the images in it are not a historical record that follows the rules and increases from generation to generation, but the result of negotiations and disputes. Other historical materials also confirm from the side that images of emperors and empresses such as "Bus of the Empress of the Ming Dynasty" are long-term "curating" projects that have undergone constant thinking, arrangement, and revision: According to Zhou Lianggong's "Reading Picture Record", At the end of Ming Dynasty, Chen Hongshou was "summoned to be a housekeeper to see the images of the emperors of all dynasties"; and in the Qianlong Dynasty in the 18th century, the images of the emperors of all dynasties were registered separately and stored in Nanxun Hall. The existing form of "Bust of the Empress of the Ming Dynasty" is probably also the result of "curation" in the mid-Qing Dynasty.

The full-body portraits of Ming Dynasty emperors, which are generally considered to be used as ancestral temple sacrifices, also contain similar "abnormalities". Like the busts, the portraits of the first few emperors of the Ming Dynasty are also shown in a three-quarter view in the full-length portraits. After the mid-fifteenth century, the portraits of the emperors of the Ming Dynasty in both albums and hanging scrolls have been changed. For a positive image. Among the portraits of the previous emperors represented in three-quarter views, the biggest difference between the full-length portraits on the hanging scroll and the busts on the album lies in the orientation of their faces: the portraits of the emperors in the album face collectively to the left, and they are facing the queens facing the right The full-body portraits roughly followed the practice of ancestral temple sacrifices, and changed their orientations according to the system of "Zuo Zhao You Mu"—except for Emperor Xuande of Ming Xuanzong, whose portrait was in the same orientation as that of his father Emperor Hongxi of Ming Renzong , to the left together (Fig. 6, 7) , rather than to the opposite right according to the Zhaomu system. The sizes of the full-length portraits are not exactly the same, and there are even large differences. The portrait of Renzong is only more than one meter high, almost half of the portraits of Taizong and Chengzu. At the same time, the huge portraits of the latter two are also quite different from the other full-length portraits in this series in style, more like they come from another series, and they were added in the "curation" process of Nanxun Temple. This sequence was added to complete the portrait set. Obviously, these portraits have undergone various adjustments and changes in the long course of history, and should not be regarded as "ancestor portraits" that were actually used in the ancestral temple and were preserved intact.

Figure 6 Xuanzong

Figure 7 Renzong

Another "known unknown" that arises from this is the question about the production of court images in the Ming Dynasty. Although later generations have various descriptions and legends about Ming Dynasty painters serving in the court, there are almost no written historical materials about the early Ming Dynasty court paintings of the same period. The "curators" of the Nanxun Temple in the Qing Dynasty were also eager to find out the authors of the images of the Ming Dynasty emperors and empresses in their hands, but their discussions also relied on written historical materials dozens or even hundreds of years after the painting was established. Similarly, if we think carefully, there are also "unknowns" about the audience of court images in the Ming Dynasty. Although the dissemination of images and information of the royal family was theoretically prohibited in the Ming Dynasty, royal anecdotes were often included in the notebook novels of the Ming Dynasty. It directly includes the portraits of Taejo, Seongjo, and Sejong (Figure 8-10) . Although these images are very different from the portraits of emperors made by the court, they retain some salient features of the faces of the three of them. Obviously, folk intellectuals can obtain general information about the portraits of emperors in the court through certain channels, and this information It can be further disseminated among the people through publications.

Figure 8 Taizu

Figure 9 Cheng Zu

Figure 10 Sejong

Professor Ke pointed out that there may have been many such royal images circulated among the people at one time in history, and the "Sancai Tuhui" and other examples in our hands are only a small part that survived, which also created another "known unknown" ", that is, we know that court images of the Ming Dynasty were disseminated among the people in a certain form, but we cannot know exactly what form, channel, and scale they were disseminated.

The loss of a large number of materials in history has created a gap in research, and the academic circle's understanding of many issues has also developed with the enrichment or re-examination of materials. For example, Professor Ke and Professor Yin mentioned in the dialogue and question-and-answer session that court art and literati art in the Ming Dynasty were once regarded as two unrelated things before scholars noticed the close communication and connection between the two. Division. Another example is the axis of "Hunting Horses" (Fig. 11), which depicts the hunting scene of Emperor Xuanzong of Ming Dynasty and his concubine. It was once listed as a work of the Yuan Dynasty by the National Palace Museum in Taipei because of its subject matter. Gradually enriched, and research in recent years has also re-examined and identified the subject matter of the work.

Figure 11 "Hunting and riding" axis

Figure 11 Part of the axis of "Hunting and Riding"

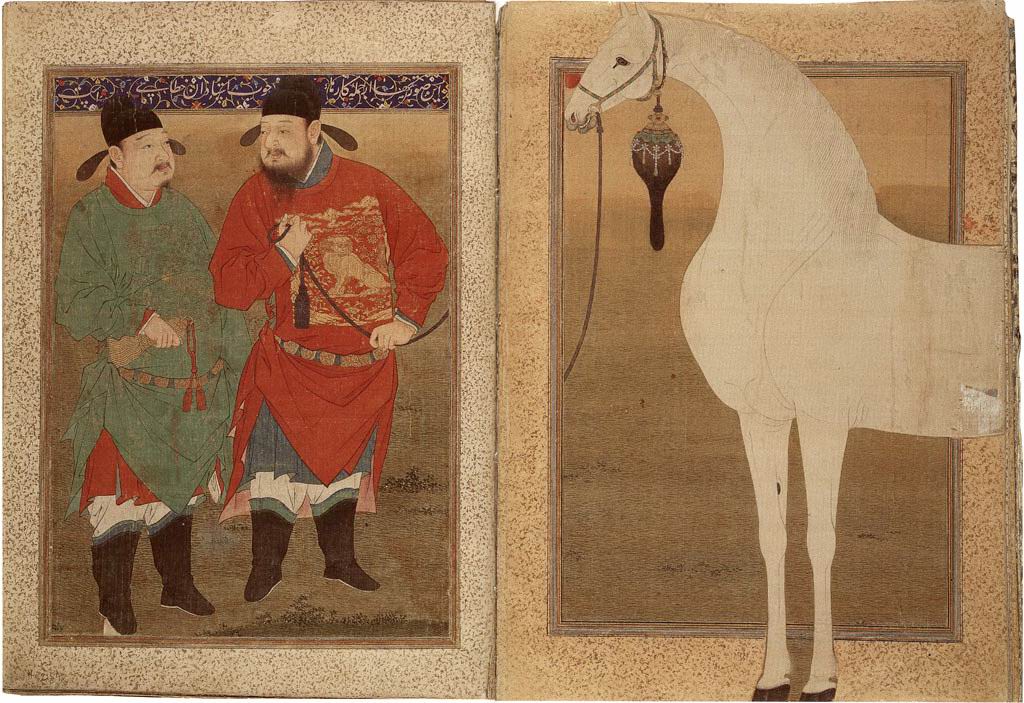

Finally, the lecture also ended with a series of bold assumptions about the "unknown". The foreign exchanges of the Ming Dynasty are widely known, which is also reflected in the art. There is enough evidence to show that a large number of Chinese artworks entered the Timurid Dynasty in Central Asia and influenced the local art production; then, did the art of the Timurid Dynasty also affect the art production of the Ming Dynasty? Is it possible that the development of the so-called Xing Le Tu in the early Ming Dynasty, which broadly includes the above-mentioned "Hunting and Riding Tu", was influenced by the large number of miniature paintings of similar themes popular in the Timurid Dynasty? (Fig. 12-14) Conquests are another major theme of the miniature paintings of the Timurid Dynasty. Is it possible that they are the battles in the lost picture of Zhu Yuanzhang’s filial piety made in 1368 mentioned at the beginning of the lecture? Some kind of blueprint for the scene? Absence of evidence is not the same as proof of non-existence. Just as there is no written evidence that Islamic metalware entered China and influenced porcelain production during the Ming Dynasty, Jingdezhen blue and white porcelain imitating Islamic metalware clearly reveals a close connection between the two; Find any Japanese screen paintings that have been handed down from ancient times, but there are many descriptions of collecting Japanese screen paintings and other artworks in Ming Dynasty books.

Figure 12 Anonymous "Horse and Chinese Attendants", China, early 15th century, from "Bahram Mirza Picture Album"

Figure 13 Miniature paintings of the Timurid Dynasty

Figure 14 "Chinese Princess" Iranian painter in the late 15th century

In the long river of history, I am afraid that the loss of materials is the norm, while the preserved parts are coincidences and accidents. So about the connection between the Timur miniature paintings and the images of court carnivals and battles in the Ming Dynasty, is it just an "unknown unknown" caused by the absence of traces of written and physical historical materials?