Ancient Chinese art historians have always paid close attention to changes and changes. The Tang and Song Dynasties were an important period in which the mainstream of Hewei in various painting disciplines shifted. Compared with painting subjects such as figures, landscapes, flowers and birds, Buddhist paintings underwent more complex and profound changes during the Tang and Song dynasties.

Recently, "Psyche of the Heart - Buddhist Paintings of Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties" was published by Peking University Press. Based on the foundation of the transformation of Buddhist paintings in the Tang and Song Dynasties, the author pays attention to the mutual influence and inspiration among Buddhist paintings of different materials such as scroll paintings, murals, and prints in that period. ) The relationship between the form, method and image of Buddhist belief. The Paper selected an excerpt from the article "Transformation of Buddhist Paintings in the Tang and Song Dynasties" for readers.

The "Tang and Song Dynasty Change Theory" was put forward by the Japanese historian Torajiro Naito (named Hunan) in the first half of the 20th century. Naito believed in the article "Summary Views of the Tang and Song Dynasties" that "the Tang Dynasty belongs to the end of the Middle Ages, while the Song Dynasty is the end of the modern age." The beginning of "the Tang Dynasty and the Song Dynasty have obvious differences in cultural nature", and from the decline of aristocratic politics and the rise of monarchy Changes in nature, changes in the nature of cronyism, changes in the economy, changes in the nature of culture, etc. are explained. Naito's "Tang and Song Revolution Theory" had a profound impact on the study of Chinese history, and Japanese academic circles formed the "Kyoto School" and "Tokyo School" around supporting or criticizing this theory. Although the claim that the Song Dynasty was the beginning of modern China was questioned and criticized by the "Tokyo School", Naito's observation of the great changes in the Tang and Song Dynasties inspired the academic circles to further study the politics, economy, culture, art and other fields of this period. Research.

Ancient Chinese art historians have always paid close attention to changes and changes. The Tang and Song dynasties were an important period when the mainstream of all painting disciplines shifted. Guo Ruoxu said in the Northern Song Dynasty: "If you talk about Buddhist and Taoist figures, scholars, women, cattle and horses, it is not as old as the past. If you talk about landscapes, forests, stones, flowers, bamboos, birds and fish, then The old is not as good as the recent." Compared with painting subjects such as figures, landscapes, flowers and birds (flowers, bamboo, poultry and fish), the changes of Buddhist paintings in the Tang and Song Dynasties are more complex and profound, not only from mainstream to non-mainstream (recent is not as good as ancient) , and important changes have also taken place in terms of material carrier, painting type, style and form, and functional meaning. ". Studying the transformation of Buddhist paintings in the Tang and Song Dynasties is the basis for understanding Buddhist paintings in the Song and later periods. Can the Song Dynasty and later be understood only as the period of decline of ancient Chinese Buddhist paintings? Do Buddhist paintings in the Song Dynasty and later have different meanings and values than those in the Jin and Tang Dynasties? To solve the above problems, it is necessary to return to the basic problem of the transformation of Buddhist paintings in the Tang and Song Dynasties.

This article is a study on the transformation of Buddhist paintings in the Tang and Song Dynasties, from the prosperity and decline of Buddhist mural paintings, the gradual activation of Buddhist scroll paintings, the rise of Buddhist paintings by literati, the emergence of Buddhist paintings related to Zen, from white paintings to line drawings, It discusses six aspects from the rationale type reproduction to the comprehension type expression. What needs to be explained is that the transition of Buddhist paintings in the Tang and Song Dynasties did not start and finish with the change of dynasties as a clear node, but a transitional process. It has expanded on the basis of following the transformation of Tang and Song Dynasties.

Buddhist Temple Murals From Prosperity to Decline

In the early Tang Dynasty (including the early Tang Dynasty and the prosperous Tang Dynasty), the paintings were dominated by Buddhist paintings and figure paintings, and the Buddhist paintings were also dominated by murals in Buddhist temples (including cave temples), especially the murals in Buddhist temples in Chang'an and Luoyang during the Xuanzong Dynasty. From the late Tang Dynasty (including the middle Tang Dynasty and the late Tang Dynasty) to the Five Dynasties, the murals of Buddhist temples in the two capitals declined suddenly, while the murals of Buddhist temples in Yizhou, Dunhuang and other areas maintained a relatively active momentum. In the Song Dynasty, compared with landscape paintings and flower-and-bird paintings, Buddhist mural paintings took a back seat and tended to decline obviously.

From the Sui Dynasty to the 14th year of Tang Tianbao (755) before the outbreak of the Anshi Rebellion, the number of Buddhist temples increased rapidly. Among them, the large Buddhist temples were concentrated in Chang'an and Luoyang, and the famous masters who were good at Buddhist paintings mostly gathered in the two capitals. The grand occasion of creating murals in Buddhist temples in Liangjing in Tang Dynasty is recorded in Zhang Yanyuan's "Records of Famous Paintings of Past Dynasties·Records of Painting Walls in Waizhou Temples in Two Beijings" and Duan Chengshi's "Temple and Pagoda Records". surface". It can be seen from the table that the creation of murals in Buddhist temples in the two capitals continued to flourish in the early Tang Dynasty, and the painters who were active in the murals of Buddhist temples, such as Yuchi Yiseng in the early Tang Dynasty, Wu Daozi and Han Gan in the prosperous Tang Dynasty, were all first-class painters. The murals of Jingfo Temple embody the highest level of painting in this period.

The creation of murals in Buddhist temples in the early Tang Dynasty was most prosperous in the Xuanzong Dynasty, marked by the activity of Wu Daozi. Wu Daozi was called into the ban because he was good at painting. He was a court painter serving the royal family. It is said that he painted the murals of temples in Liangjing "over three hundred rooms". There are as many as sixteen Buddhist temples. Wu Daozi's Buddhist paintings have a great influence, and the style of Buddhist paintings he created is known as "Wu's style".

In the early Tang Dynasty, most of the temples that preserved a large number of paintings by famous artists were imperial court official temples or royal merit temples. For example, Chang'an Ci'en Temple was built by Emperor Gaozong for his mother, Empress Wende when he was in the East Palace, and Xingtang Temple was built by Princess Taiping for his mother's Wu family. Anguo Temple was built by Ruizong after he ascended the throne, using his old house in the Fan Dynasty; Qianfu Temple was built by Lu Wang Li Xianshe's house; Luoyang Jing'ai Temple was built by Prince Li Hong for Emperor Gaozong and Empress Wu; and so on. Judging from this, the prosperity of the creation of murals in Buddhist temples in the Tang Dynasty should be mainly due to the economic support of the royal family and nobles.

The prosperity of mural painting in Buddhist temples in the early Tang Dynasty was also seen in the Dunhuang area. The Mogao Grottoes in this period were unmatched by other periods in terms of the number of caves opened and the artistic level of mural paintings. Judging from the existing records of the merits of opening the caves and the inscriptions on the portraits of the donors, it can be seen that the large and medium-sized caves in this period were mainly funded and built by local prominent families.

The Anshi Rebellion was the turning point for the mural creation of Buddhist temples in the two capitals of the Tang Dynasty to turn from prosperity to decline. From the “List of Mural Paintings in Buddhist Temples in Two Beijings of the Tang Dynasty”, it can be seen that the number of murals in Buddhist temples in Liangjing and active Buddhist painters in the late Tang Dynasty decreased sharply. In addition, paintings with non-religious themes such as landscapes, pine stones, flowers and birds accounted for a considerable proportion of Buddhist murals. It shows that the aesthetic taste of Buddhist temples changed at that time.

In the late Tang Dynasty, the creation of murals in Buddhist temples in the two capitals declined suddenly, while the creation of murals in Buddhist temples in Yizhou, Dunhuang and other areas maintained a relatively active momentum. Since Yizhou Emperor Xuanzong and Xizong came to seek refuge and was less disturbed by the war, the creation of murals in Buddhist temples was relatively prosperous in the middle Tang Dynasty and the early Song Dynasty. During the ten-year siege of Tubo and the early period of Tubo rule, the construction of the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang basically stagnated. more active.

The creation of murals in Buddhist temples in the early Northern Song Dynasty was relatively active, and the murals of Daxiangguo Temple in Tokyo (now Kaifeng City, Henan Province) were the most famous, such as Gao Yi, Shi Ke, Gao Wenjin, Gao Huaijie, Wang Daozhen, Li Yongji, Li Xiangkun, etc. successively participated. Wang Guan, Wang Ai, Sun Mengqing, etc. were good at Buddhist temple murals in this period.

However, on the whole, the creation of murals in Buddhist temples in the Song Dynasty is still in decline, and the most direct manifestation is the sharp decrease in the number of murals in Buddhist temples. The most prosperous Buddhism in the Song Dynasty was Zen. Zen was developed in China. It did not pay attention to the use of images to promote Buddhist principles like Buddhism in the Jin and Tang Dynasties. Become a Buddha. In addition, the emerging literati class did not support the creation of Buddhist temple murals like the previous nobles did. Another manifestation of the decline in the creation of murals in Buddhist temples in the Song Dynasty is the decline in artistic standards. This is related to the fact that most mainstream painters no longer engage in mural creations. The creation of Buddhist scroll paintings has become more active, and the painting of Buddhist murals has increasingly become a "painter". field.

Buddhist Scroll Paintings Become Active

In the early Tang Dynasty, many Buddhist painters were good at both mural painting and scroll painting. By the Five Dynasties and Song Dynasty, the creation of mural painting and scroll painting began to separate, that is, some Buddhist painters no longer excelled at both mural painting and scroll painting. Most painters no longer engage in mural creation, and Buddhist scroll paintings are relatively active.

In the early Tang Dynasty, Buddhist painters were good at murals and scroll paintings. Yuchi Yiseng, Wu Daozi, Yang Tingguang, Lu Lenga, etc. were not only active in the paintings on the walls of Buddhist temples, but also painted on silk paper, such as "Xuanhe Painting Book" recorded Huizong Imperial Palace That is to say, they have a certain number of Buddhist scroll paintings in their possession. Although there are many fake works among them, it is enough to prove that they have participated in the creation of Buddhist scroll paintings.

From the late Tang Dynasty to the early Northern Song Dynasty, some Buddhist painters, such as Sun Wei, Gao Yi, and Gao Wenjin, still focused on murals in their creations. Some Buddhist painters also shifted their focus from murals to scroll paintings. Zhou Fang was the most famous Buddhist painter in the late Tang Dynasty. Zhangjing Temple, Shengguang Temple, Dayun Temple, Guangfu Temple and Xuanzhou Chanding Temple all had his murals. However, he is more famous for his paintings of ladies and portraits. His creative focus It should be on a scroll rather than a mural. In the late Tang Dynasty, in addition to painting murals in Shengshou Temple, Dashengci Temple and Jinhua Temple in Yizhou, Zhang Nanben also painted "more than 120 frames" of water and land paintings for the Water and Land Academy of Baoli Temple in Yizhou, which were hung on the wall of the Water and Land Academy Complete set of vertical shafts on. Former Shu Guanxiu was famous for his paintings of Arhats. For example, his painting "Sixteen Frames of Arhats" recorded in "Yizhou Famous Paintings" is a hanging scroll, and there is no record of him painting murals. Most of the rubbings of stone carvings passed down as Guanxiu's "Sixteen Arhats" are preserved today. Shi Ke, who entered the Song Dynasty from the later Shu, tried to paint murals for Shengshou Temple in Yizhou and Xiangguo Temple in Tokyo. However, he should be better at Buddhist scroll paintings. " and "Parade of Heavenly Kings" and so on.

After the rise of literati painting in the middle and late Northern Song Dynasty, mural paintings and large-scale and paired paintings were despised by literati painters. "Hua Ji" said that Li Gonglin was in order to distance himself from secular painters. Shangyun's wonderful cloth is skillful, but I have not seen his great generosity." Li Gonglin mostly used paper for his paintings and did not make large-scale or double-sided paintings, which had a great influence on the creation of Buddhist paintings. For example, the volume of "Vimalakirti's Performance and Teaching Picture" collected by the Palace Museum is a paper version. Made by Qing.

Under the influence of the concept of literati painting, in the middle and late Northern Song Dynasty and later, the creation of mural paintings and scroll paintings gradually became distinct. Most painters no longer excelled in both mural paintings and scroll paintings, and the painting of Buddhist scroll paintings appreciated by literati became more active.

Although Buddhist paintings were not the main specialty of Liang Kai and Liu Songnian, the court painters of the Southern Song Dynasty, they all have Buddhist scroll paintings in existence, such as Liang Kai’s "Shakyamuni Coming out of the Mountain" scroll (collected by Tokyo National Museum), "Eight Eminent Monks" scroll (collected by the Shanghai Museum), Liu Songnian has the three-axis "Arhat Picture" (collected by the National Palace Museum, Taipei), etc., but there is no record of them painting murals.

The creation of complete sets of water, land and Luohan scroll paintings in the Song Dynasty was relatively active. For example, Su Shi in the Northern Song Dynasty set up the Water and Land Ceremony for his deceased wife to hang eight water and land paintings in the upper and lower halls, a total of sixteen; Sixteen Axis”; in the Southern Song Dynasty, there was a workshop specialized in painting Buddhist scroll paintings for export, and most of them painted images of Arhats, represented by the axis of “Five Hundred Arhats” co-painted by Zhou Jichang and Lin Tinggui; and so on.

Corresponding to the contempt of mural paintings by literati painters, the mural paintings of Buddhist temples in the Song and Jin Dynasties were increasingly reduced to the creative field of "painters". For example, in the third year of Shaosheng in the Northern Song Dynasty (1096), there is an inscription in ink in the Daxiong Hall of Kaihua Temple in Gaoping, Shanxi: "Bingzi powdered this west wall on June 15th, and the painter Guo Fa recorded it and illuminated the wall." There is an ink book inscription in the Manjusri Hall of the Mountain Temple, which reads: "Seven years ago, Dading painted the Lingyan Courtyard on the 28th day. Runxi." In the above two examples, the painters both call themselves "painters", and Wang Kui's official title should be "painter under the imperial court".

The rise of literati Buddhist painting

Compared with professional Buddhist paintings, literati Buddhist paintings emphasize the artist's literati status, and embody the literati's emotions and interests in Buddhist paintings. During the rise of literati painting in the middle and late Northern Song Dynasty, Buddhist painters also faced the predicament of declining professional painting. Li Gonglin and others actively transformed and participated in the creation of the literati painting system, which made Buddhist painting an important part of it at the beginning of the rise of literati painting.

In the late Tang Dynasty and the Five Dynasties, there appeared some professional Buddhist painters with high cultural literacy. For example, Zhou Fang was the noble son of "youqingxiangjian", "good at literature"; ; Shi Ke's "Comprehensive Confucianism"; and so on. In addition, Wang Wei, who was hailed as the ancestor of literati painting by later generations, also painted portraits of eminent monks.

Those who clearly advocated the concept of literati painting (scholar painting) were Su Shi, Li Gonglin and Mi Fu in the middle and late Northern Song Dynasty. Su Shi was a Jinshi in the second year of Jiayou (1057). He was able to paint dead wood, bamboo and stone. literacy, taste", or "inner 'spirit' or 'thinking'". It is worth noting that although Su Shi admired literati paintings, it did not prevent him from admiring the professional painter Wu Daozi as a "painting saint" and writing inscriptions and postscripts praising professional Buddhist paintings.

Li Gonglin was a Jinshi in the third year of Xining (1070), and he made friends with Su Shi, and was influenced by Su Shi in terms of painting creation and tasting concepts. Li Gonglin is good at painting Avalokitesvara statues with novel styles, such as Avalokitesvara with Long Belt, Avalokitesvara Lying on a Stone, and Avalokitesvara in Freedom. According to the records of the Song Dynasty, the Buddhist paintings he painted include "Hua Yan Bian", "Statue of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva", "Statue of Goddess", "Statue of Amitabha", "Statue of Drunken Monk", "Statue of Saint Monk in the Western Regions", "Statue of Eighteen Venerables", " Big Brahma Statue", "Dharma Protector Statue", "Picture of Rest and Silence" (Author's Note: Eminent Monk Statue), etc.

Li Gonglin is the most influential Buddhist painter after Wu Daozi. He lived in an era when professional Buddhist paintings were no longer brilliant and gradually declining, and it was also an era when the mainstream of Buddhist paintings shifted from murals to scroll paintings. Li Gonglin almost single-handedly made Buddhist painting one of the earliest painting disciplines involved in the creation of literati paintings. The line drawings he created had a profound influence on later generations. In addition, Li Gonglin's painting skills are comprehensive, and he is good at Buddhism, Taoism, figures, pommel horses, and landscapes, which provides an example for later literati painters who are also good at Buddhist paintings.

In the Song Dynasty, Qiao Zhongchang, Seng Fanlong, Zhou Chun, Seng Dezheng and Yang Wujiu learned from Li Gonglin. "Painting Book" stated: "The scholar Qiao Zhongchang, when he was a teacher (Li Gonglin), seemed to be a fake. When he went to the south to Wuxing monk Fanlong and his teacher, but the characters were mostly made of water patterns, and they were a little lacklustre." Qiao Zhongchang painted " A Picture of Eminent Monks Chanting Sutras", Lou Yao in the Southern Song Dynasty once wrote a postscript for this picture. Fanlong has a volume of "Eighteen Arhats" (collected by the Freer Art Museum in the United States), and there is a signature "Written by Fanlong" on the rocks in the picture. In addition, "Hua Ji" records Zhou Chun, Seng Dezheng, and Yang Wujiu's teacher Li Gonglin, among them Zhou Chun "takes poetry and painting as Buddhist affairs...the scholar-officials often travel with him", and Seng Dezheng "became an instructor in Pingjiang" before he became a monk. Yang Wujiu is good at both poetry and painting, and they all have high cultural accomplishment.

Zhao Meng, who entered the Yuan Dynasty from the Song Dynasty, was a key figure leading the development of literati painting. He was good at painting people and horses, landscapes, bamboos, stones, flowers and birds, and he was also able to paint images of Arhats and eminent monks. It is the only authentic Buddhist painting in existence. In addition, he has repeatedly painted "The Original Image of Zhongfeng Ming", "Participating with the Leftovers", and "Pine and Stone Buddhist Monk Picture".

Emergence of Buddhist paintings related to Zen

Zen painting is a concept that has appeared frequently in the study of Chinese and Japanese painting history since the 20th century. However, there is no such word in ancient Chinese literature, and there are only approximate references such as "painting Zen" and "painting Zen". The earliest scholars who studied the relationship between Zen and Chinese painting, Suzuki Daizhuo and Kilong Jin, were more cautious in their works, and did not formally put forward the concept of Zen painting. Regarding what is Zen painting, there is no relatively clear and consistent opinion in the academic circles, and there is no evidence that the appearance of this kind of painting is mainly driven by Zen Buddhism. Therefore, when discussing this kind of painting, the author intends to use "related to Zen Buddhism painting (or Buddhist painting)".

Judging from the records of painting history, although the style of reduced brushwork appeared in the Five Dynasties and the Northern Song Dynasty, it was more influenced by cursive brushwork and splash-ink painting, and related to the pursuit of indulgent and weird aesthetic taste. It is not related to Zen. No direct relationship. Li Wei of the Northern Song Dynasty's "De Yu Zhai Paintings" records that Zhang Tu of Houliang made clothes patterns, "Using thick ink and thick brushes like cursive script, trembling and flying, very bold and unrestrained; The brush is light in color, detailed and careful, and there is not a single stroke." It is not certain whether what Li Wei saw is the authentic Zhang Tu, but at least it shows that the style of reducing the brush strokes with rough and simple clothing patterns and using fine brushes on the face appeared in the Northern Song Dynasty. Shi Ke, who was active from Western Shu to the early Song Dynasty, is also considered to be related to the style of subtracting brushwork. For example, "Huajian" states that he "paints characters with dramatic strokes, but the face, hands, and feet are drawn, and the clothing patterns are made with rough brushwork."

In the Southern Song Dynasty, there appeared a batch of rough and simple brush and ink paintings that were in line with the spirit of Zen and interesting. The themes involved Buddhism and Taoism, figures, landscapes, flowers and birds, etc. The main characteristics of Buddhist paintings related to Zen described in this article are as follows: 1. The use of ink and wash in a rough and simple style, that is, the style of reduced brush strokes; 2. The subject matter is related to Buddhism (mainly Zen), and reflects the spirit and interest of Zen Buddhism; The Zen monk praised it. Among them, the first and second points are necessary conditions. If the painting can also meet the third point, it can be said that it has a close relationship with Zen.

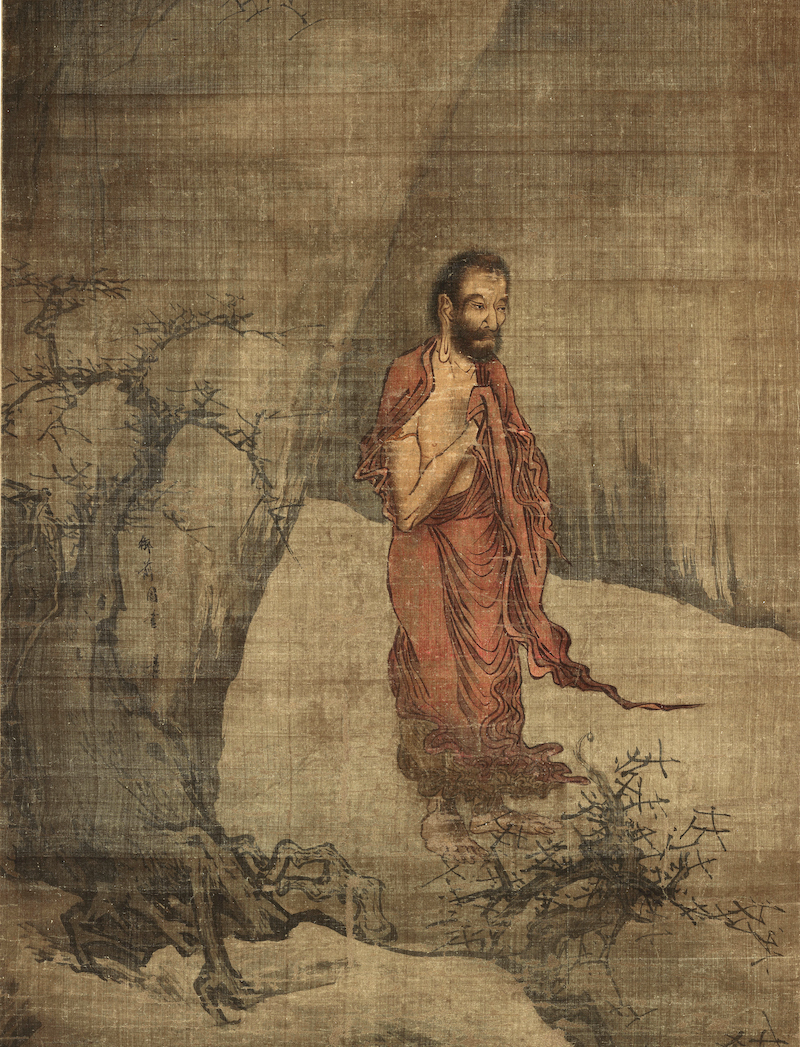

Figure 1-1 Axis of Sakyamuni coming out of the mountain, Liang Kai, Southern Song Dynasty, Tokyo National Museum

Liang Kai was a member of the Jiatai Academy of Painting in the Southern Song Dynasty. The "Pictures and Paintings" stated that he was not granted the gold belt by the emperor, and he was addicted to alcohol. Hastily, it is called minus pen". The extant "Sakyamuni Leaving the Mountain" (Fig. 1-1) and "Eight Eminent Monks" by Xu Bangda are both recognized as authentic works of Liang Kai. The themes of the two pictures are directly related to Zen Buddhism, and both are mainly ink and wash, with rough and powerful lines and vivid depictions. Compared with professional painting in the usual sense, the background of mountains and rocks can be called "minus pen". There are also scrolls of "Six Patriarchs Cutting Bamboo" (collected by Tokyo National Museum) and "Six Patriarchs Torn Sutras" scroll (collected by Mitsui Memorial Museum of Japan) in the Buddhist paintings signed by Liang Kai. However, it is not the authentic work of Liang Kai.

Figure 1-2 Axis of "Avalokitesvara" Collection of Dade Temple in Japan, Fachang, Southern Song Dynasty

The interpretation is often a monk at the end of the Southern Song Dynasty, named Muxi. "Pictures and Paintings" says that he "likes to paint dragons, tigers, apes and cranes, reeds, geese, mountains and rivers, trees and stone figures, all of which are made with brush and ink, with simple meanings and no need for decoration. ", and his painting style is also a minus style. There is a scroll of Fachang's "Avalokitesvara" in the collection of Daitokuji Temple in Kyoto, Japan (Figure 1-2, which is in the same group as the "Ape" and "Crane" axes). Ink strokes belong to the rough and simple style of ink and wash.

Figure 1-3 Shakyamuni’s Coming Out of the Mountain, Anonymous Southern Song Dynasty Collection, Cleveland Museum of Art, USA

It is worth noting that in the late Southern Song Dynasty, a batch of anonymous Buddhist paintings with a minimalist style appeared, and most of the paintings had inscriptions of praise from Zen monks. The axis of the anonymous "Sakyamuni Coming Out of the Mountain" in the Southern Song Dynasty collected by the Cleveland Museum of Art in the United States (Fig. 1-3), the background of the picture is very simple, only the ground is represented by ink brush and moss, and the face and hands of Sakyamuni are enough to be sketched with a fine brush, and the cassock Outlined with a minimalist rough brush, there is a praise inscribed by Chan Master Zhijue Daochong in the fourth year of Chunyou (1244) of the Linji School. The axis of "Sakyamuni Coming Out of the Mountain" in a similar style is preserved in the Freer Art Museum in the United States and the Seattle Art Museum. The axis of the anonymous "Li Ao Asking Questions" in the Southern Song Dynasty (collected by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the United States) shows the Zen koan in which Tang Li Ao asked the Zen Master Yaoshan. Sketched with a fine brush, the clothing pattern is also extremely simple and scribbled. There is an inscription of praise by Zen Master Yanxi Guangwen of Linji Zong in the Southern Song Dynasty.

Compared with the Buddhist paintings of Liang Kai and Fachang, the above-mentioned anonymous Buddhist paintings, which are mostly inscribed by Zen monks, are all in a very simple style, even scribbled, which usually directly embodies the purpose of enlightenment in Southern Zen and is closely related to Zen. From the perspective of time, it is not the Zen monks or believers who promote the appearance of the pen-reduction style, but the use and transformation of the pen-reduction style.

From white drawing to white drawing

On the basis of integrating the northern and southern regions and Chinese and foreign painting styles, Buddhist paintings in the Tang Dynasty derived painting forms that not only conformed to the local aesthetic taste but also had the characteristics of the times. Among them, Wu Daozi's white paintings are the most representative, and the white paintings focus on the expression of strong lines. Power, in line with the carrier form of murals. In the middle and late Northern Song Dynasty, Li Gonglin developed a line-drawing technique suitable for expression on paper and silk. Line-drawing emphasized the elegance and taste of lines, which matched the way of tasting on the desks of literati studies.

After Buddhist paintings were introduced to China, they paid special attention to the expression of lines. The expressive power of lines in Buddhist paintings in the prosperous Tang Dynasty reached a new height. For example, Zhang Yanyuan said that Wu Daozi's paintings are "majestic in spirit and charm, which can hardly be tolerated by plain elements; the handwriting is upright and free, so it can be seen on the wall", and a new painting form - white painting appeared. White paintings are repeatedly mentioned in "Famous Paintings of Past Dynasties" and "Temple and Tower". "Hell Change" and so on. Shi Shouqian noticed that Zhang Yanyuan repeatedly divided the production of murals into two stages of "drawing" and "completeness" in "Famous Paintings of Past Dynasties". Among them, "drawing" is the main stage, which is performed by painters with higher reputation, and "cheng" is the second stage. If it is important, it should be done by a lower-level painter. For example, Wu Daozi went there every time he wrote a painting, and his disciples Zhai Yan and Zhang Zang mostly painted it. It is also recorded several times in the literature that good white paintings were damaged by vulgar workers. example of. It can be judged from this that white painting does not emphasize the lack of color, but to highlight the lines, and the color application cannot damage the expressiveness of the lines.

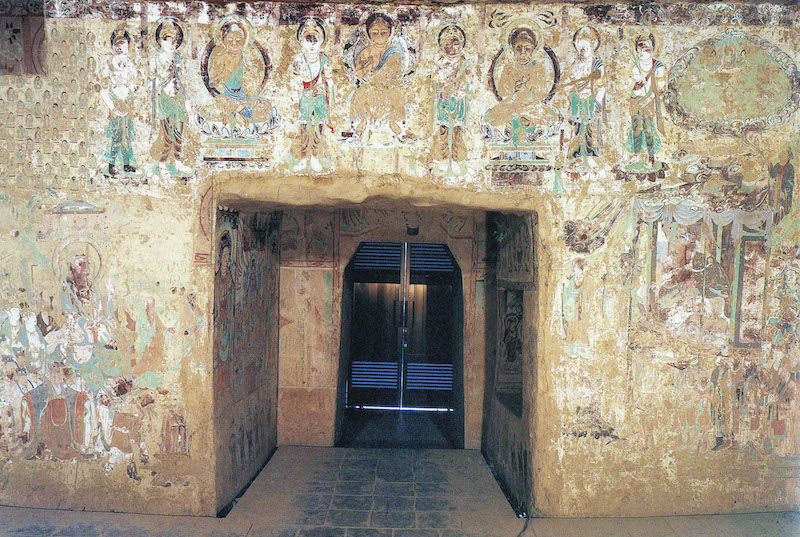

Figure 1-4 The Vimalakirti Statue of Vimo Transformation The east wall of the main room of Cave 103 in Mogao Grottoes in the prosperous Tang Dynasty

In the early Tang Dynasty, the transportation between Dunhuang and the Central Plains was smooth, and the styles and styles popular in the Central Plains were often reflected in Dunhuang murals in time. The Vimalakirti statue on the east wall of the main chamber of Cave 103 of Mogao Grottoes in the prosperous Tang Dynasty (Fig. 1-4) is mainly expressed by lines. The lines are bold, smooth, and full of elastic power. At a turning point, the beard, hair, and flesh are strong, and the face, hands, feet, and white clothes of the characters do not emphasize color smudges. Only the robe worn by Vimalakirti is dyed ocher, which is consistent with Wu Daozi's style of painting and the form of white paintings recorded in the literature.

Line drawing is generally considered to be created by Li Gonglin, a literati painter in the Northern Song Dynasty. In the literature of the Northern Song Dynasty, it was mentioned that Li Gonglin's paintings were not full of color, such as Zen Master Huihong said: "When Yu Guanbo painted a lot, he was very generous with the meaning of Gu and Lu, and the meaning was endless, so he didn't use five colors, but Bo knew it. " Zen Master Hui Hong said that Li Gonglin did not use color in his paintings because he got the ancient ideas of Gu Kaizhi and Lu Tanwei, and the reason why he did not use color in his paintings was "the incomplete state of meaning" (getting the meaning without exhausting the form). Documents of the Southern Song Dynasty highlighted the relationship between Li Gonglin's lack of color and the interest of literati. For example, Deng Chun said that the reason why Li Gonglin's paintings "exceeded the world" was "not using alchemy powder"; Going away from powder and daisy, light ink, elegant and super friendly, such as a secluded person and a victorious man, brown clothes and grass shoes, are actually simple and far away, and it is true that embroidered cicadas are the most important"; and so on. The academic circles call Li Gonglin's painting style, which emphasizes the expression of lines and does not use color, the line drawing. It should be noted that the appearance of white painting is because the artist thinks that coloring is relatively secondary, so he let his disciples or other people complete it. Although there are some unpainted in the end, it is not the original intention of the artist; while white drawing is intentional by the artist. , its purpose is to pursue the elegant interest of the literati, and the final completed work is not color-coded.

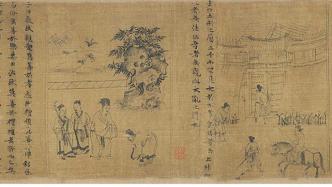

Figure 1-5 Scroll of Vimalakirti's Performance Teaching, Li Gonglin (Biography) of the Northern Song Dynasty, Collection of the Palace Museum

Li Gonglin’s line-drawing Buddhist paintings are no longer in existence. The “Vimo Performance and Teaching Picture” collected by the Palace Museum (Fig. 1-5) reflects the characteristics and achievements of line-drawing in the Song and Jin Dynasties. Comparing with the Vimo statue in Cave 103 of Mogao Grottoes in the prosperous Tang Dynasty, one can intuitively feel that the line drawn in the "Vimo Show and Teaching Picture" should have evolved from the white painting in the prosperous Tang Dynasty. The lines in the two pictures are both tactful and vigorous , smooth, and parallel arcs are often used, but the lines of white painting tend to be thicker, bolder, and neat, while the lines of white drawing are more elegant, flexible, and subtle. This is not only related to the brush used and the way of painting, but also to the painter and Connoisseur's aesthetic taste. The line drawing created by Li Gonglin had a great influence on subsequent Buddhist paintings and became one of the main expressions of Buddhist paintings in the Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties, and its influence was not limited to literati painters, but also included professional painters such as Wang Zhenpeng and Zhu Yu.

From rational representation to comprehension performance

Disguised form (or Jingbian) was the most popular theme of Buddhist paintings in the Tang Dynasty. In a narrow sense, disguised form refers to the painting based on one or one type of Mahayana Buddhist scriptures (from late Tang to Song Dynasty, it also includes popular literature such as Bianwen and Zaju). Large-scale Buddhist images, although there is no lack of the painter's fantastic imagination and artistic expression, are mainly faithful reproductions of Buddhist scriptures, embodying religious, classic and aristocratic interests. In the Northern Song Dynasty, with the decline of temple murals and the gradual activation of Buddhist scroll paintings, large-scale disguises suitable for wall performances were no longer popular, and themes suitable for hand scrolls and hanging scrolls became more popular, such as the "simplified version" of disguised forms, Arhat monks, etc. Statues, Zen koan paintings, single or combined Buddha and Bodhisattva statues, water and land paintings (parts of Buddhist gods), statues of the Ten Kings of Hell, etc., and are mainly expressed based on the understanding of Buddhism by the common people (including the artist himself) at that time. It incorporates the taste of literati, Zen or common people. Let's take "Vimo Change", "Arhat Picture" and "Jiebo Picture" as examples to illustrate.

Figure 1-6 "Vimo Change" East Wall of the main room of Cave 220 of Mogao Grottoes in the early Tang Dynasty

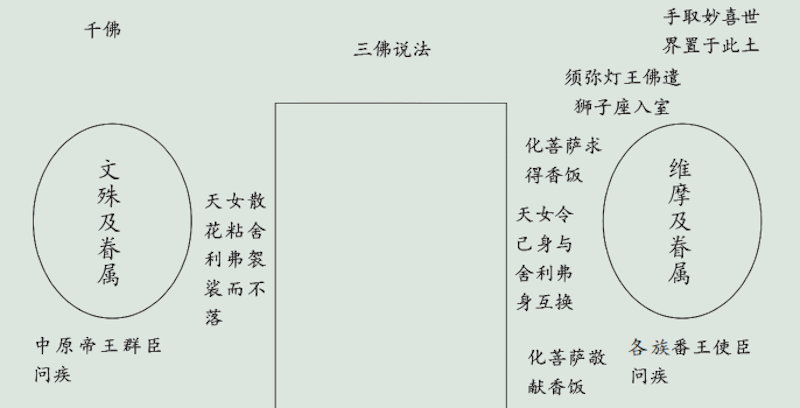

"Vimo Change". "Vimalakirti Bian" is one of the popular disguises in the Tang Dynasty. It is mainly drawn based on the translation of "The Sutras of Vimalakirti" translated by Kumarajiva in the later Qin Dynasty. to other plots. In the early Tang Dynasty, the large-scale and mature "Vimo Bian" began to appear. Among the existing works, the earliest date is "Vimo Bian" on the east wall of the main room of Cave 220 in Mogao Grottoes in the 16th year of Zhenguan (642) (Fig. 1-6). Zhongshu, Weimo and their relatives are located on both sides of the cave door. Below them are the emperors of the Central Plains and their officials, and the envoys of various ethnic groups and kings asking questions, showing a total of twelve independent small pictures. The schematic diagram of plot location in this figure (Figure 1-7) is as follows:

Since then, the plot of "Vimo Bian" in Dunhuang has been further enriched and evolved on the basis of the cave map, especially "Vimo Bian" on the east wall of the main room of Cave 61 in Mogao Grottoes of the Five Dynasties is more representative. The eight titles indicating the content of the storyline intuitively show that it was a faithful reproduction of Buddhist scriptures in disguise at that time.

Figure 1-7 Schematic diagram of the location of the plot of "Vimo Change" on the east wall of the main room of Cave 220 in Mogao Grottoes

Li Gonglin's "Vimo Show and Teaching Picture" collected by the Palace Museum inherited the antithetical composition of "Vimo Bian" since the Tang Dynasty, but made important changes according to the form of the scroll and the taste of literati: 1. Reduce and weaken the performance of the storyline , which mainly highlights the status of the gods as dependents. For example, although the plot of the goddess scattering flowers and sticking Shariputra’s cassock without falling off is retained, the goddess and Shariputra stand in front of Vimo and Manjusri respectively, and at the same time take into account their identities as family members; Behind him, the storyline related to it is not described, but only highlights his identity as a member of Vimalakirti; second, in the absence of Buddhist scriptures, the good fortune boy and Buddha Boli in the "Manjushri New Style" schema , Manjusri transformed the old man and King Khotan into Manjusri’s retinue, indicating that important changes had taken place in the creative concept of Buddhist paintings during this period—classic schemas, like Buddhist scriptures, could be the basis for the creation or transformation of Buddhist paintings; The white painting shown in the murals was changed to a white drawing suitable for paper hand scrolls. "Vimo Performance and Teaching Picture" can be said to be "Vimo Change" simplified and transformed by the painter based on the understanding of literati in the Song and Jin Dynasties.

Figure 1-8 One of the 500 arhat portrait axes, Southern Song Dynasty, Zhou Jichang, Japan Dade Temple Collection

"Arhat Picture". After Tang Xuanzang translated "The Records of the Great Arhat Nanti Mi Duo Luo's Dharma" (hereinafter referred to as "Fa Zhu Ji"), there appeared the statues of Arhats in the strict sense-the drawing of the sixteen Arhats, "Fa Zhu "Records" does not clearly stipulate the image of the arhats, saying that in addition to protecting the Dharma and possessing supernatural powers, the arhats also "show various forms, conceal sacred rituals, and be like ordinary people", which provides a basis for the artist's imagination. Arhat paintings in the Song Dynasty mainly evolved in the direction of Sinicization and secularization. Among them, the most important manifestations are the appearance of Arhats subduing the dragon and subduing the tiger. Book (collected by the Palace Museum). There is no direct basis for the appearance of Arhats subduing the dragon and subduing the tiger, but were created by the Song people based on their own understanding. The richer imagination of Arhats is reflected in the "Five Hundred Arhats", the most representative one is the "Five Hundred Arhats" painted by Lin Tinggui and Zhou Jichang in the Southern Song Dynasty (Figure 1-8), five Arhats are painted on each axis , a total of 100 axes, the images of Arhats in the picture are either for enlightenment in daily life, or for displaying various supernatural powers, or for protecting and holding fasting offerings at Dharma meetings, or for accepting offerings from various gods.

Figure 1-9 Scroll of Arhats in Red, Yuan Dynasty, Zhao Mengfu, Collection of Liaoning Provincial Museum

Zhao Mengfu of the Yuan Dynasty borrowed from and transformed the images of Arhats of the previous generation in "Arhats in Red" (Figure 1-9) to make them conform to the taste of literati, mainly through two methods: one is to trace the ancient meaning of the Tang Dynasty. In the inscription behind the picture, Zhao Mengfu said that the picture "roughly has an ancient meaning", which mainly refers to the ancient meaning of the Tang people. In addition to the influence mentioned in the inscription that he was influenced by Tang Lulenga's painting of Arhats, which "obtained the mood of the people of the Western Regions". The patterns, red clothes and green rocks also reflect the characteristics of Tang paintings. The second is to integrate into the interest of Zen. "Arhat in Red" was painted in the eighth year of Dade in Yuan Dynasty (1304), when Zhao Mengfu followed Ming Ben to learn Zen and became more and more sophisticated. Many elements in this picture contain the interest of Zen. For example, the arhat resting in the shade of the bodhi tree should be related to Zhao Mengfu's experience of following Mingben's meditation and Shenhuatou, and it is the projection of his inner emotions. In addition, ancient Bodhi trees, kudzu vines, safflowers, etc. can also be connected with Zhao Mengfu's experience and thoughts of practicing Zen. However, it should be pointed out that the above-mentioned Zen interest is not a purely religious image, but a taste transformed by Zhao Mengfu that can be appreciated by literati. Zhao Mengfu traced the ancient meaning of the Tang Dynasty and projected the literati's understanding, enlightenment and emotion of Zen into Buddhist paintings, which promoted the integration of Buddhist paintings with literati's interests at a deeper level in terms of thoughts and emotions, and made Buddhist paintings transition from professional paintings to literati paintings. transformation provides direction.

"Uncovering the Bowl Picture". Although "Miscellaneous Treasures Sutra: Guizimu's Lost Predestined Relationship" mentions that Guizimu tried her best to remove the bowl to save her young son Pinjialuo, but the "Revealing the Bottom Picture" which shows a complicated scene should be mainly based on "Guizimu Jiebo". "Jaju" and other popular literature. The earliest and complete "Jiebo Tu" in the existing literature records is a mural on the left corridor wall of the main hall of Daxiangguo Temple in the Northern Song Dynasty. Zhuyu's "Jie Bo Tu" volume (collected by Zhejiang Provincial Museum) adopts the opposite composition commonly used in disguise in the Tang Dynasty, and its schema should have evolved from murals. In addition, this picture also adopts the line drawing style created by Li Gonglin, a literati painter in the Northern Song Dynasty, to keep a distance from the paintings of vulgar craftsmen and fit the aesthetic taste of the emerging literati class. The "Jiebo Tu" volume collected by the Palace Museum in Yuan Dynasty abandoned the opposite composition in Zhu Yu's "Jiebo Tu" and adopted a more dramatic composition method, which is also more suitable for hand-scroll viewing. Relatively speaking, the religious attributes and characteristics derived from murals in this picture have been greatly weakened, while the characteristics of common people's interest and suitable for hand-scroll shapes have been highlighted. The above two examples of "Jie Bo Tu" scrolls provide typical examples of the transformation of traditional Buddhist schemas from mural paintings to hand scrolls.

Shadow of Heart - Buddhist Paintings in Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties

epilogue

In a nutshell, the transformation of Buddhist paintings in the Tang and Song Dynasties is mainly reflected in: 1. In terms of material carrier, Buddhist mural paintings were the mainstream in Tang Dynasty, and Buddhist scroll paintings in Song Dynasty; 2. In terms of painting types, professional Buddhist paintings in Tang Dynasty were the mainstream. As the mainstream, the Song Dynasty was more typical of literati Buddhist paintings and Buddhist paintings related to Zen; 3. In terms of style and form, Tang was represented by white paintings, and Song Dynasty was more typical of white drawings; 4. In terms of function and meaning, Tang Dynasty Focusing on the faithful reproduction of the teachings of Buddhist scriptures, Song focuses on the understanding of Buddhism by the scholars and believers (including the painter himself) at that time. The transformation of Buddhist paintings in the Tang and Song Dynasties is not only reflected in material materials, styles and forms, but also in functional meanings, creations, and appreciation concepts, which is the basis for the further evolution of Buddhist paintings in the Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties.

Note: The author of this article is a research librarian of the Painting and Calligraphy Department of the Palace Museum. The original title of the article is "Transformation of Buddhist Paintings in Tang and Song Dynasties".