On April 6, the exhibition "The Rossetti Family" was exhibited at Tate Britain, focusing on the famous 19th-century British Rossetti family, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his wife Elizabeth West. Dahl, and Gabriel's sister Christina, explore their influence on British culture and art.

It is reported that this is the largest exhibition of Rossetti's oil paintings in the past 20 years, and it is also the most comprehensive review of Elizabeth Siddall's works of art. According to art critic Jonathan Jones, the poetess Christina and her poetry are the real geniuses in this exhibition about the Pre-Raphaelites, above Gabriel's sensual, luminous beauties.

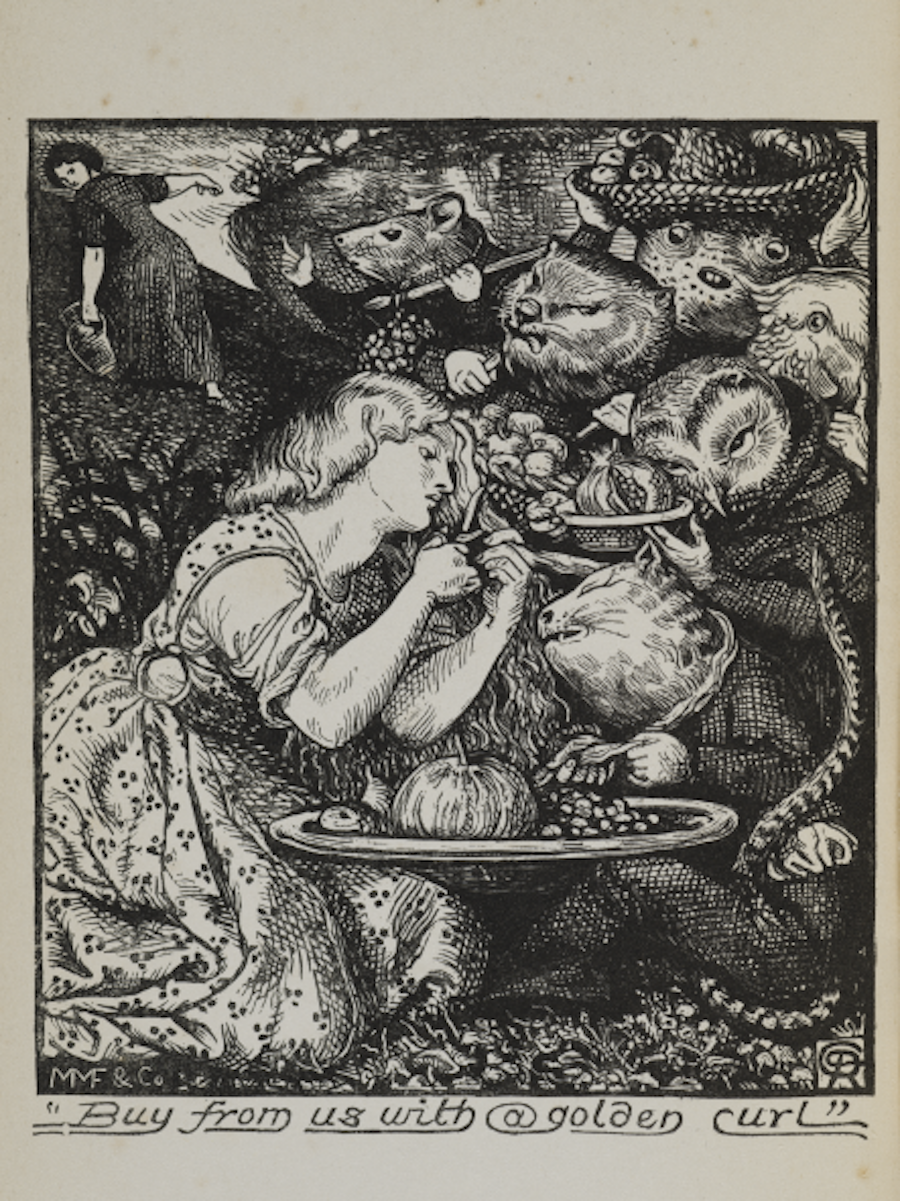

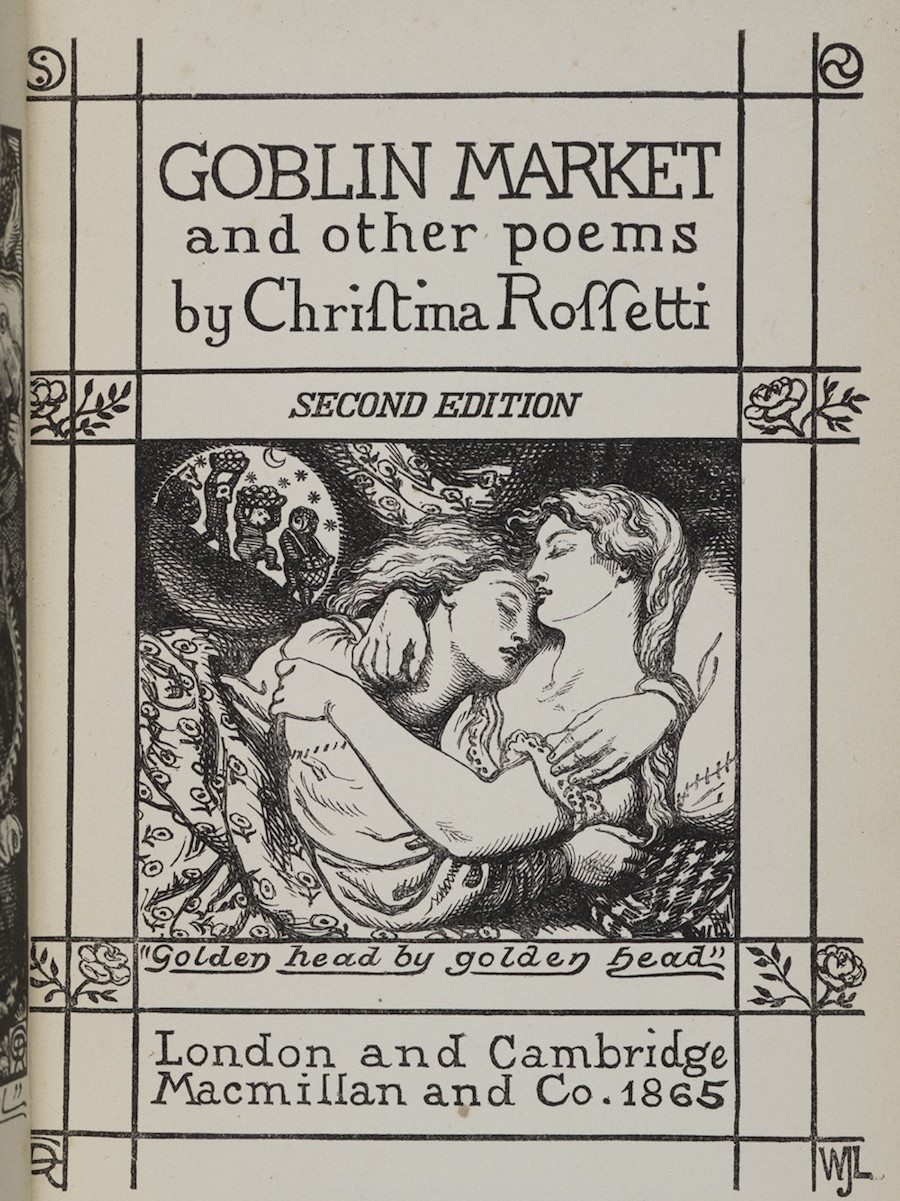

In 1848, 20-year-old Dante Gabriel Rossetti (Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1828-1882) co-founded the "Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood" with two friends. The outdated dogma of the school advocates returning to the artistic style of the early Renaissance in the 15th century. His works are famous for their rich details, strong colors and complex compositions. Gabriel's younger sister, Christina Rossetti (Christina Rossetti, 1830-1894), began writing poetry at the age of 12. Her representative works include "Elf Market" and "In the Cold Midwinter". Christina, on the other hand, was critical of the Pre-Raphaelites.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Proserpine, 1874

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Lady Lilith, 1866-1868

From Tate Britain's celebration of the 'radical' and 'revolutionary' Pre-Raphaelites, from the very first room, it becomes clear who the true genius of the Rossetti family was - — Poetess Christina Rossetti. You can hear a reading of her poems here, including "Colour," which celebrates color with an almost childlike, mentally clear image: " What is yellow? A ripe, juicy pear is. (What is yellow? pears are yellow/Rich and ripe and mellow.)" .

Christina Rossetti, Goblin Market, 1865

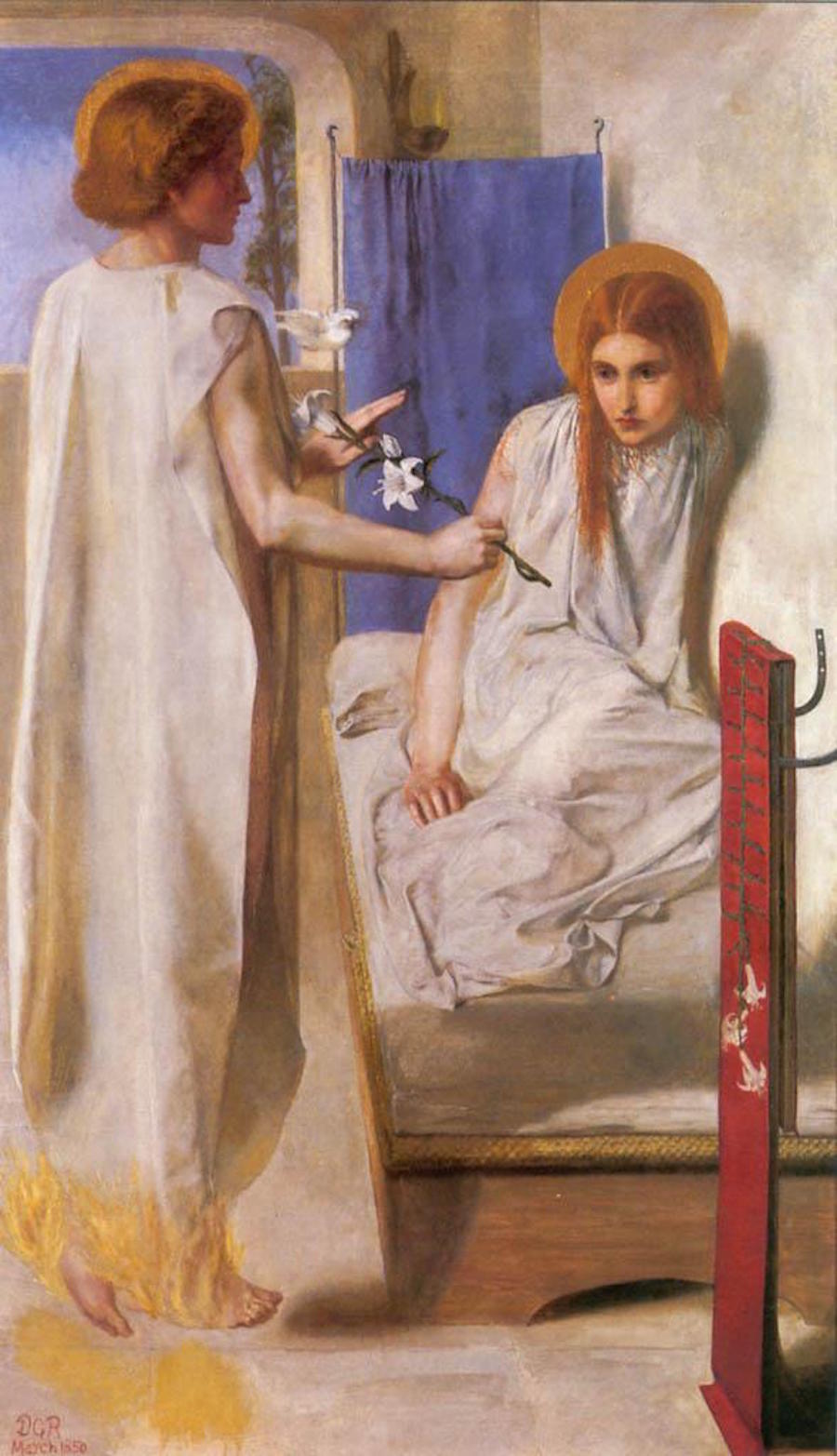

Unfortunately, while you're listening, you're forced to watch The Annunciation, written in 1849-1850 by her brother Dante Gabriel Rossetti, which The work is placed in the middle of the exhibition hall like an icon. While Christina's images have a crystalline precision that makes them almost timeless, this work is entirely for Victorian lovers, housed here like some kind of taxidermy, a This far-fetched reference to medieval art is neither medieval nor modern.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, The Annunciation

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, La Ghirlandata (La Ghirlandata), 1873

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Monna Vanna, 1866

While the exhibition strives to juxtapose Christina's verse with the artwork of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, you can only go so far in bringing literature into the gallery through the verse printed on the walls of the exhibition . Cristina's steady, quiet voice was drowned out by Dante Gabriel's lush paintings of beauties. Dante Gabriel Rossetti never seems to have painted anyone or anything from life, ever. His pseudo-Renaissance paintings are heavily conceived with symbolist eroticism. It turns out his paintings do. When he sketches his models, his lovers, he never sticks to what he sees but transforms it with abstract, simplified lines. This is not to say that he is an abstract artist, but sketches empty idealized figures.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was a group of ordinary male artists who came together in 1848 to fanatically deck out their art in borrowed 15th-century religious robes and advertise themselves as the savior of society. The text on the exhibition walls would have us believe that they were "revolutionaries" who "wanted to express themselves authentically in art and poetry based on lived experience and nature". They were a group of "young men and women" despite the emphasis on fraternity in their name. We are thus told that John Everett Millais' 1850 watercolor "A Baron Numbering his Vassals" actually depicts the 1840s British class conflict. is this real? It seems to me more like a calm depiction of medieval folklore.

Millais "A Baron Numbering his Vassals"

In a long exploration of Rossetti’s unfinished painting “Found,” the exhibition pushes his hyperbolic claims about the Pre-Raphaelites to the point of absurdity. In this painting, a "street woman" prostrate against a wall is rescued from death by a countryman. In a series of half-painted and half-painted canvases, Rossetti immersed himself in the sensual face of his model, Fanny Cornforth, undermining the work's supposed social message in a comical way. The exhibition presents all of this as a radical, revolutionary indictment of Victorian capitalism. In fact, it is the collision of Rossetti's eroticism and narcissism, and his attempt to create a painting with a conscience. Of course, he didn't finish Discovery because he knew it was a bad painting.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Found

If there was a Pre-Raphaelite painter who fit the show's critique of the socialism of the Victorian social order, like feminism, it was William Morris, not Rossetti. Morris was actually a socialist. When he was trying to design Utopia, Rossetti was having an affair with his wife Jane and was painting her. When the morally fanatical John Ruskin admired and bought not only Rossetti's art, but that of his lover and eventual wife, Elizabeth Siddal, Rossetti Dee and Fanny Cornforth betray Siddall together.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, The Girlhood of Mary Virgin, 1848-1849

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Paolo and Francesca da Rimini, 1855

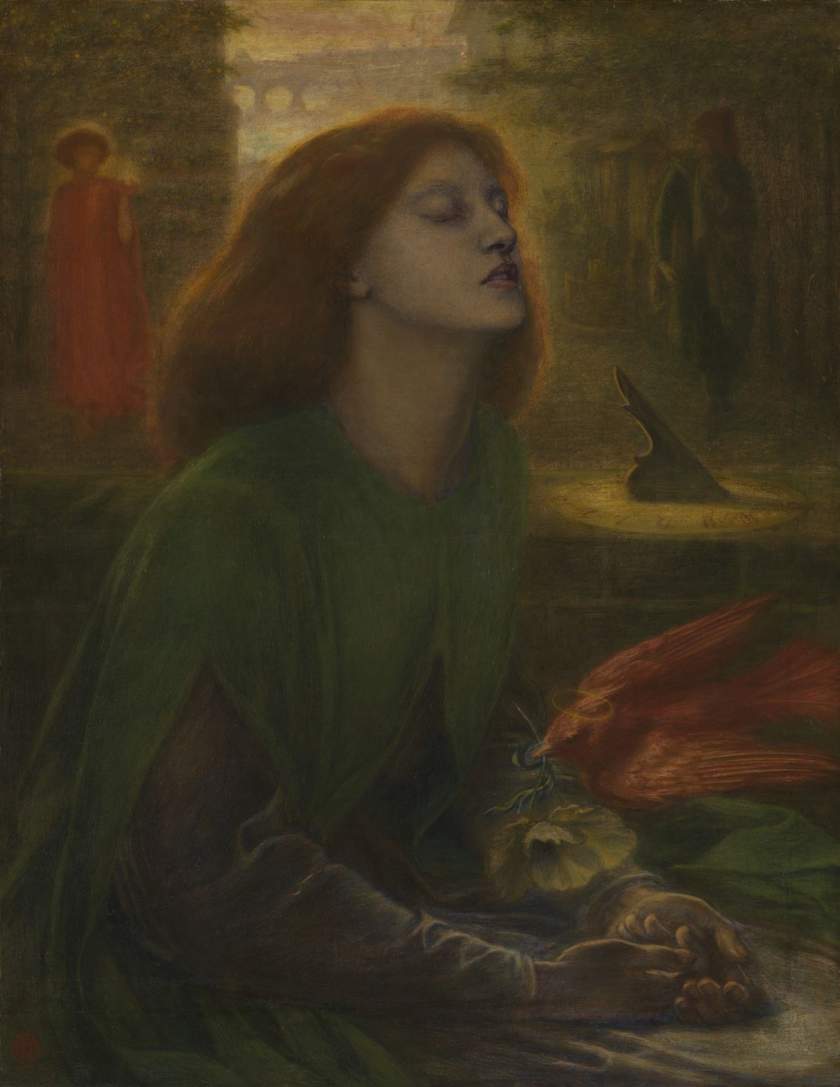

It is worth mentioning that Gabriel Rossetti's artistic creation and private life are inseparable. He married his pupil Elizabeth Siddall, and had two lovers, Fanny Cornforth and Jane Morris, the wife of Rossetti's friend William Morris. These three women frequently appear in Rossetti's paintings, Siddall as the embodiment of perfection, Fanny as a plump and sensual image, and Jane as an ethereal goddess.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Beata Beatrix, 1863, with Siddall as model, epitomizes Rossetti's passion for depicting beautiful women

Siddharth by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, pen drawing, 1854

The show makes the factual error of recklessly treating the Rossettis as noble and progressive. The wall text explaining Rossetti's 1859 painting "Bocca Baciata" tells us that the painting shows "The Decameron, a sensuous medieval poem by Giovanni Boccaccio. Italian Poetry". The same statement is used in the catalog. But there is no medieval "poem" called the Decameron. The Decameron is the founding work of Italian prose: a collection of fantastic tales, the ancestor of the modern novel.

Rossetti was actually illustrating the seventh story of the second day of the Decameron. In this story, an oriental princess is shipwrecked on her way to marry an Algarve prince and then hunted down (actually raped) by a series of men. So the painting is a far cry from the “romantic radicalism” the exhibition claims for it. In portraying his lover, Fanny Cornforth, as Boccaccio's princess, he seems to be playing a dirty joke, or sexual braggadocio. How ridiculous.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Bocca Baciata, 1859

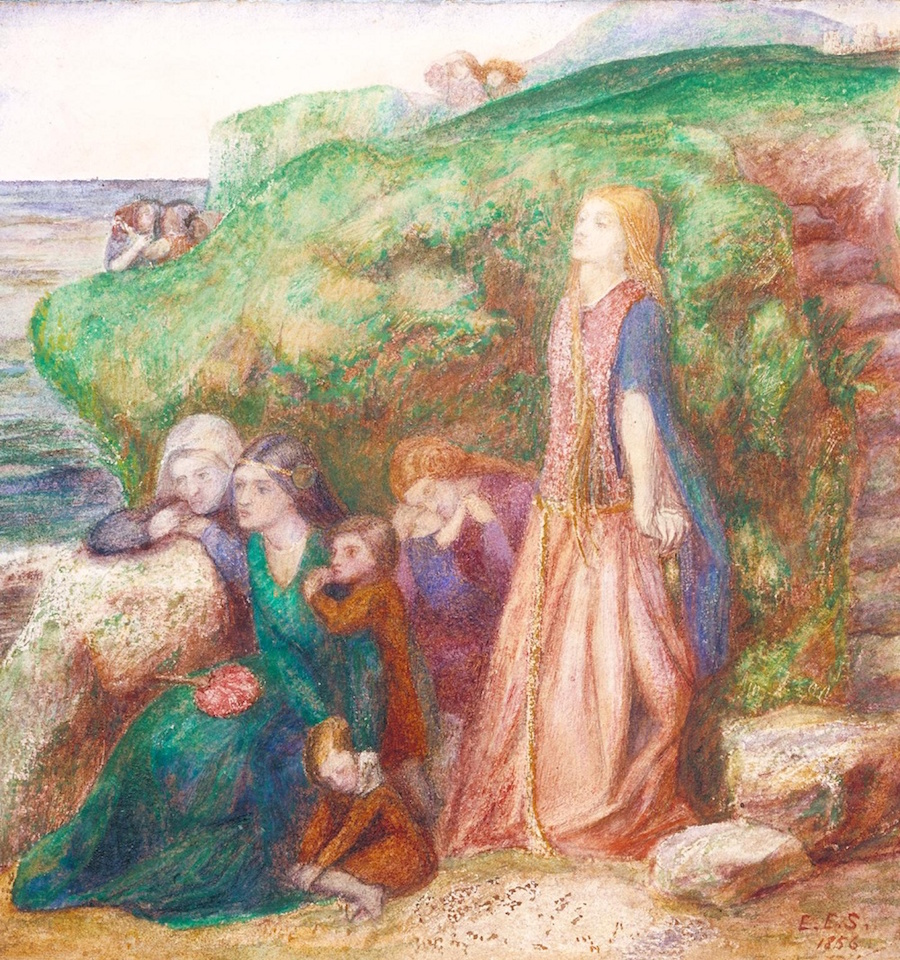

Dante Gabriel Rossetti was not a radical little man, at least he supported Siddall as an artist. Siddall's paintings, like his, passionately depict King Arthur's romances in bright colours. But when they combined self-taught naive drawing with Pre-Raphaelite fantasies, they often appeared clumsy and powerless. Then again, in general, Pre-Raphaelite male works are more technically sophisticated.

Elizabeth Siddall, Sir Patrick Spens, 1856

Elizabeth Siddall, Lady Clare, 1854-1857

Although Millais’s Ophelia belongs to the Tate collection, the fact that it is not included in the exhibition also leaves Siddall floating in eerie delight. It may be because the curator wants to get rid of Siddhar's "myth". Siddall is a real person, but she soon becomes a figure of Rossetti's fantasy. On display here is a lock of her hair, which was cherished by Rossetti. He later asked his friends to open her grave at Highgate Cemetery in London.

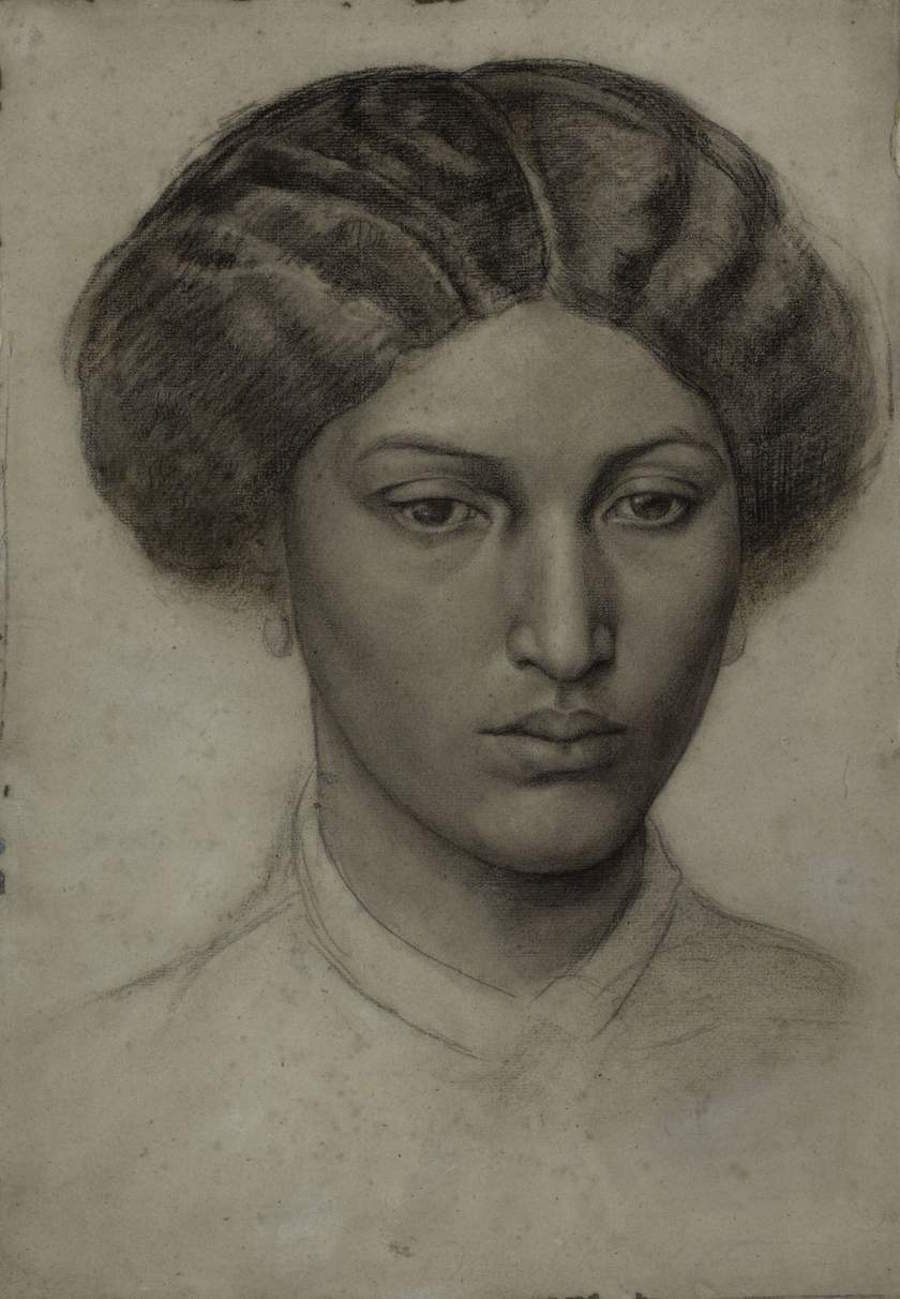

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Head of a Young Woman, 1863-1865

Christina Rossetti, Goblin Market, 1865

Christina has information about her brother, and her poem "In an Artist's Studio" is printed on the exhibition wall. Christina's poetry evokes a mysterious model, "a face looks out from all his canvases" . This is the ubiquitous "nameless girl" that plagues the artist's work, "the painter feeds upon her face by day and night" .

This is the muse of the Pre-Raphaelites. This exhibition clearly fails to dispel that myth. Christina Rossetti sees the role women have always had in her brother's art: to be fed.

The exhibition "The Rossetti Family" runs from April 6th to September 24th.

(This article is compiled from The Guardian, the author Jonathan Jones is an art critic.)