In major German museums, there are thousands of important cultural relics from the Qing Dynasty in China. How did these cultural relics get from Beijing to Germany? Were they trophies illegally looted by Germany in colonial wars?

The Paper learned that the traceability project "Tracking Boxer Relics" jointly launched by seven museums in Germany the year before last will be completed in November this year, aiming to answer these questions. At the same time, the German side has also established cooperation with the Palace Museum to trace the 70 representative cultural relics selected by the German side. This is the first time in the Western world to systematically study the lost cultural relics after the Eight-Power Allied Forces invaded China.

The statue of Mongolian Prince Kekiyamzan, from Ziguang Pavilion. The portrait was put up for sale at a Berlin art dealer shortly after the Eight-Power Allied Forces crushed the Boxer Rebellion. It is hidden in the Berlin Museum of Ethnology and is suspected to be one of the cultural relics looted by Germany from Beijing during the Eight-Power Allied Forces period.

Image courtesy of Berlin Ethnographic Museum.

In the Chinese exhibition hall of the German Museum of Ethnology at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, there are two exquisite portraits of Chinese heroes. These two paintings were once hung in the Ziguang Pavilion in Zhongnanhai. Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty specially asked the painter to draw them in recognition of the outstanding generals who opened up the territory. Historically, the Ziguang Pavilion was the place where the emperors of the Ming and Qing Dynasties watched riding and shooting and inspected military officials. Later, it was also used to receive foreign envoys, which has important political and military symbolic significance. At present, in addition to the two hanging portraits, the German Museum of Ethnology and the German Asian Art Museum have collected dozens of portraits of Ziguang Pavilion heroes.

According to the staff of the German Museum, these portraits may have been brought to Germany after the German army took part in the suppression of the Boxer Regiment by the Eight-Power Allied Forces. After the outbreak of the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, the Eight-Power Allied Forces invaded Beijing, and Empress Dowager Cixi and Emperor Guangxu fled to Xi'an. After the war, the city of Beijing was divided and occupied by the Eight-Power Allied Forces for a year. During this period, a large number of royal cultural relics were looted and flowed into the art market.

The Ziguang Pavilion happened to be located in the German occupation area, and the hundreds of portraits preserved in it were lost during this period, and eventually scattered into the hands of museums and private collectors around the world. German researchers estimate that German museums may hold thousands of artifacts from the Boxer period.

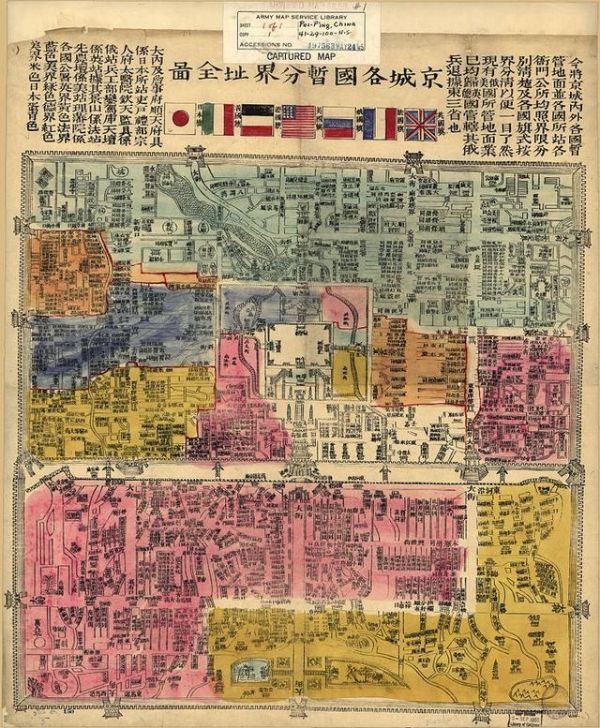

At that time, the pink area on the map occupied by the Eight-Power Allied Forces in Beijing was the German-occupied area.

How did these cultural relics get from Beijing to Germany? Were they trophies illegally looted by Germany in colonial wars?

At the end of 2021, seven German museums jointly launched the "Tracking Boxer Relics" traceability project, aiming to answer these questions. "How these artefacts came to German museums has only been roughly studied, and little is known about the history behind them," says the project's website.

The seven museums include - the Asian Art Museum and Ethnographic Museum of the Berlin State Museum, the MARKK Museum in Hamburg (formerly the Hamburg Museum of Ethnology), the Hamburg Museum of Arts and Crafts, the Grassi Museum of Applied Arts in Leipzig, the Frankfurt Museum of Applied Arts, and the Munich Five Continental Museum.

Representatives of German museums participating in the traceability project "Tracking the Boxer Relics" introduced themselves at the Humboldt Forum project seminar in March this year. Image courtesy of project leader Dr. Christine Howald.

The seven museums, with financial support from the "German Foundation for Lost Cultural Relics", started research in November 2021 and are expected to be completed by November 2023. Our research aims to gain insights into Boxer-period artworks held in German museums and to reflect on Germany's colonial past.

Dr. Christine Howald, project leader and deputy curator of the German Central Archives, said that this is the first time in the Western world to systematically study the lost cultural relics after the Eight-Power Allied Forces' war of aggression against China. Previously, under the coordination of the State Administration of Cultural Heritage, Germany established a cooperative relationship with Shanghai University. However, due to the impact of the epidemic, experts from the two countries were unable to exchange visits, resulting in slow progress in research. Until the end of 2022, the project partner turned to the Palace Museum.

In view of the large number of cultural relics, the tracing work is challenging. The German side has currently selected 70 representative cultural relics, including porcelain, Buddha statues and scrolls, and submitted this list to the Palace Museum for joint research.

Scholars lining up to enter the Humboldt Forum

Why did Germany take the initiative to trace the source and plunder cultural relics?

In recent years, European society, especially Germany, is undergoing reflection on colonial history. Although Germany’s global expansion was later than other European powers, before the First World War, it once became the third largest colonial empire after Britain and France, with colonies all over Africa, the South Pacific and my country’s Jiaozhou Bay.

In German media, calls to examine colonial history have grown louder, the culmination of years of protests by African-American civil rights groups and leftist academics. They demanded that streets named after colonists be renamed and that German states include colonial history in school curricula.

The death of George Floyd, a black American, has further triggered German society's thinking about racism and colonial history. This change in social concepts has also been reflected at the policy level. When the new German government came to power, it promised in the party coalition agreement that it would pay more in-depth attention to colonial history.

As a place for collecting cultural relics from all over the world, German museums have also become the main battlefield of public opinion.

In September 2021, the German Humboldt Forum Museum project, which took 20 years and cost 680 million euros to build, will be open to the public. The building of the Humboldt Forum was originally the palace of Kaiser Wilhelm II. The emperor had great colonial ambitions. It was under his leadership that Germany became a colonial power. The Humboldt Forum, home to the Museum of Ethnology and the Museum of Asian Art, houses a large collection of colonial artifacts looted from around the world. Although the Humboldt Forum project was originally aimed at shaping the image of Berlin as a world cultural center, due to its close connection with colonial expansion, it became a focus of controversy for reflection on colonial history.

In recent years, many German museums have had to start examining their collections due to protests and pushes from former colonial countries, especially African countries. Already a small collection, such as Benin bronzes and bones collected after the German massacre in Namibia, has been returned to its country of origin.

It is worth mentioning that, since Africa is the main stage of German colonial activities, the current discussion of colonial history in German society mainly focuses on Africa, and little is known about Germany’s colonial activities in China.

Christine Howald, the initiator of the Boxer Cultural Relics Traceability Project, said in an interview with a special contributor to The Paper: "It is undoubtedly very important that the German museum's cultural relics traceability work mainly focuses on African cultural relics. But China It has also experienced a brutal history of colonization. As an Asian art expert, I think Germany should pay equal attention to this aspect of research.”

She emphasized that the traceability of cultural relics during the Boxer Rebellion period is still in its early stages, and the issue of the return of cultural relics goes beyond the scope of traceability of cultural relics, and involves areas such as museum policy and diplomacy. However, if it is determined that these cultural relics were illegally looted by German colonists, she believes that these cultural relics should be returned. She said: "We should at least be able to openly discuss the future of these cultural relics. From my personal perspective and the perspective of a cultural relic traceability worker, I hope these items can be returned to China in the future."

Ms Kerstin Pannhorst, project research assistant and coordinator, said: "These artefacts are in our museum's storage rooms and we have a duty to ask ourselves, where did they come from? Do they fit in here? ? What do we do if it’s not suitable?”

Experts from the Tresden Museum in Germany introduced the Ziguang Pavilion meritorious service map suspected to be looted in the museum

150 German experts discuss Boxer relics

In March, the Humboldt Forum hosted a two-day workshop hosted by the Tracing the Boxer Relics group, which attracted 150 curators, art historians, sinologists and historians from the German-speaking world , to jointly discuss the issue of German theft of art in China during the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion. Experts presented some of the artifacts of questionable provenance in their museum collections and discussed questions and difficulties they encountered in their research.

Pannhorst (Pannhorst) said that they deliberately opened this seminar to the public: "Because, compared with history, these artworks are things that people can actually see and touch, and they are a way to understand colonial history. "

Cord Eberspächer, a German sinologist, said at the meeting that 1900 was a critical year for Chinese cultural relics in German museums, just as 1933 was an important year for the Nazis to loot Jewish art. "As long as it is a Chinese cultural relic that enters a German museum after 1900, its source must be examined."

Susanne Knödel, curator of the MARKK Museum in Hamburg, also previously told the author that since 1900, the quality and quantity of Chinese cultural relics in the museum have grown significantly, which makes her very interested in these collections. source has been questioned. With the support of the new curator in 2017 for traceability and return work, Knödel began to systematically count suspicious cultural relics.

The Boxer Rebellion began in Shandong Province and quickly spread throughout northern China. During this period, Klind, the German minister to China, was killed by soldiers of the Qing Dynasty, which became the fuse for the Eight-Power Allied Forces to jointly send troops to suppress the Boxer Regiment. Pegold estimated at the seminar that Kaiser Wilhelm II sent a total of 20,000 soldiers to China. When seeing off these expeditionary forces, he delivered the infamous "Huns Speech": "Leave no prisoners of war, shoot them. Just as the Huns under King Etzel's command thousands of years ago are still prestigious in the legends that have been handed down to this day Therefore, Germany's prestige should also be spread widely in China, so that no Chinese will dare to look sideways at the Germans."

However, by the time these German soldiers arrived in China, the fighting was mostly over. Pergold said: "Germany just caught up with the carnival of the victors. German soldiers can put the plundered things in their pockets at will."

Old Shadows of the Eight-Power Allied Forces Invading China

Old Shadows of the Eight-Power Allied Forces Invading China

The looting by soldiers from various countries filled the streets and alleys of Beijing with palace artworks, and the German Museum also sent personnel to Beijing to purchase cultural relics. According to the research of art historian Niklas Leveranz, the Berlin Ethnographic Museum sent Müller, the assistant director, to Beijing in 1901. Although the funds he received were only 10,000 marks, through his relationship with the German army, he obtained a number of cultural relics at low prices, sometimes even for free. According to records, Muller sent a total of 117 wooden boxes of cultural relics back to Berlin. During his stay in Beijing, he bought two portraits of heroes in Ziguang Pavilion, and after returning to China, he bought a large number of statues of heroes from German soldiers.

According to Leveranz's research, most of the surviving Ziguangge artworks were once in German museums. However, Germany experienced two world wars, and many cultural relics and documentary records were destroyed. After World War II, during the Soviet occupation of Berlin, a large number of German museum collections were transferred to St. Petersburg as spoils of war. It is not clear how many Chinese cultural relics were destroyed or exiled to the Soviet Union.

Identifying the provenance of artifacts is challenging

In the face of a huge number of lost cultural relics, it is not easy to determine their source. There are not many cases like Ziguangge Heroes that can be clearly defined as looting cultural relics. Confirming the provenance of cultural relics requires a high degree of technical expertise and knowledge, involving multiple fields such as art history, archaeology, sinology and materials science, which requires a lot of time and resources.

Christine Howald, project leader, believes that Germany sometimes lacks expertise in identifying cultural relics. "Some Chinese experts pick up a cup and look at whether it is light or heavy, which can provide a lot of information about the background and authenticity of the cultural relic." She hopes that the cooperation with experts from the Palace Museum can help the research of the cultural relic itself. German experts can only look for clues from German archives, and sometimes can find out who sold the cultural relics to the museum, but whether the cultural relics left China through legal channels still needs further research. In this regard, Germany also hopes to share more information with China.

On the other hand, the background of cultural relics in the late Qing Dynasty is extremely complicated. After Beijing was occupied, in addition to the looting by the Eight-Power Allied Forces, there were also Chinese people taking advantage of the chaos to loot. The economic situation of the royal family in the late Qing Dynasty deteriorated day by day. In order to maintain the standard of living, some data show that Pu Yi and other members of the royal family sold a large number of cultural relics, and even court ladies and eunuchs privately sold the treasures in the palace. It is not easy to determine whether a cultural relic was really robbed by the Germans.

"Of course, this was all done against the backdrop of colonialism. If Britain hadn't forcibly opened China's door in the middle of the 19th century, and countries began to sign unequal treaties with China, China would not have fallen into that political, social and economic predicament. ’ thinks Christine Howald. She added: "We have no way to confirm the origin and migration path of each object, which requires researchers to classify which are confirmed looting, which are suspicious and which are safe and legal artifacts."

Against the complex historical background of the colonial period, the Association of German Museums has published a guide to advise and assist museums in storing colonial collections. The guide proposes that under the unequal power relationship brought about by colonialism, if it can be proved that cultural relics were obtained through improper means, and the country of origin puts forward a return request, it is recommended that Germany return these cultural relics. At this time, the traceability of cultural relics plays an important role. Of course, the guidelines are not legally binding. Some critics believe that since the work of tracing the origin of cultural relics takes a long time, it may be used by some museums as an excuse for delay and become a stumbling block to the return of cultural relics.

The researchers of the "Boxer Relics" project said that so far, their museum has not received any recourse from the Chinese side.

Huo Zhengxin, a professor at the School of International Law at the China University of Political Science and Law, said that existing international law does not provide sufficient protection for cultural relics lost in China in the early 20th century. "From the current legal level, it is not easy for China to recover cultural relics from this period, but Germany's behavior at that time was definitely immoral. From an emotional and moral point of view, it should be returned. It really depends on the Germans themselves To what extent do you want to do it?"

He suggested that China should take advantage of Europe's process of reflecting on its colonial history, actively select some representative cultural relics, and start negotiations with Germany through communication, cooperation and diplomatic coordination to explore whether the return of Chinese cultural relics can be facilitated.

Mixed voices in German society

Germans have limited knowledge of Germany's colonial past in China, and of those who do, not all support criticism of that history. Renata Fu-sheng Franke, a German Sinologist, published an article in the German media, criticizing the project of "Tracing the Origin of Boxer Relics". She wrote, "China has never been a colony of ruthless exploitation by Western powers like some African countries. The Chinese have neither lost their entire cultural heritage nor their identity because of defeat."

Ms. Frank is the granddaughter of Otto Franke, the founder of German Sinology, and her mother is Chinese. She believes that China has a long art market tradition, calling Chinese art in her home a legitimate purchase. She also claimed that the overseas circulation of Chinese cultural relics has played an important role in the understanding of Chinese culture in the West, so the cultural relics of this period should not be completely denied, and large-scale traceability work is a waste of resources. "The Chinese did not ask for the return of the cultural relics (looted by Germany) at all. This false sense of self-blame and eagerness to return the Germans is not conducive to active cultural mediation and international understanding."

In response, Christine Howald also wrote an article in response, admitting that not all cultural relics from China were obtained through illegal or immoral means, and the key is to conduct detailed research on their provenance. She writes: "In cultural heritage research, we not only have to reconstruct the path of art, but also question the behavior of our predecessors." She believes that public institutions such as museums have a moral obligation to check the provenance of their collections: "In discussing the German We should spare no effort on the issue of responsibility for our colonial past.”

The "Tracking Boxer Relics" project plans to hold an international seminar in English in early 2024, hoping to attract more researchers from China and around the world to participate. At the end of the project, the research team will develop a guide that other museums can provide a basis for when researching Boxer artifacts. The researchers hope that the Palace Museum will be involved in writing the guidelines to ensure that Chinese voices and perspectives are included.

Considering the complicated and time-consuming tracing of cultural relics and the lack of a strong legal framework in Germany, it is unlikely that Germany will return cultural relics invaded by the Eight-Power Allied Forces in the next few years. However, should German museums continue to display artefacts that have been clearly identified as looted?

To the author's question, several curators at the seminar gave affirmative answers. They believe there is value in presenting these controversial artefacts in an exhibition that can introduce visitors to this forgotten history. Birgitta Augustin, curator of the Asian Art Museum in Berlin, said: "This history is the history of the artwork itself, the history of the collection, and the history of our museum. It should be made known to visitors in a more obvious way."

Of course, this concept is also quite controversial. Some people think that continuing to display these cultural relics in museums is also a continuation of plundering and disrespect for the country where the cultural relics originated. This issue involves the trade-off of multiple interests and values, and it is not easy to find a correct approach recognized by everyone. At present, some museums have adopted the method of co-curating with experts and communities from the country of origin of cultural relics, which is conducive to eliminating the single European perspective in the narrative of the exhibition, leaving the right to speak to the country of origin of cultural relics, and reflecting respect and balance for cultural diversity , so that the audience can better understand the original cultural significance of the cultural relics.

(The author is a freelance writer, focusing on cultural and historical issues, often living in Berlin)