If time could be turned back hundreds of years, how would people living in the Qing court understand time? What role does time play in daily life in the Forbidden City? How did Qing palace paintings express the invisible time in a tangible artistic way?

The newly published book "Time Image in the Forbidden City - A Perspective on Qing Dynasty Palace Paintings" (Guangxi Normal University Press) involves multiple time issues in Qing palace paintings, including the Central Plains, the West, Manchuria, self, country, ancient and modern times, and time and space. and other seven levels, to explore the image meaning and cultural connotation of Qing Dynasty palace paintings.

The presentation of clocks in Qing palace paintings

Due to the love and promotion of the Qing emperors, the Western clocks introduced to China in the late Ming and early Qing dynasties were widely used in the palace. Western timekeeping methods also subtly affected the court life of the Qing Dynasty. Correspondingly, depictions of clocks also appeared in Qing palace paintings.

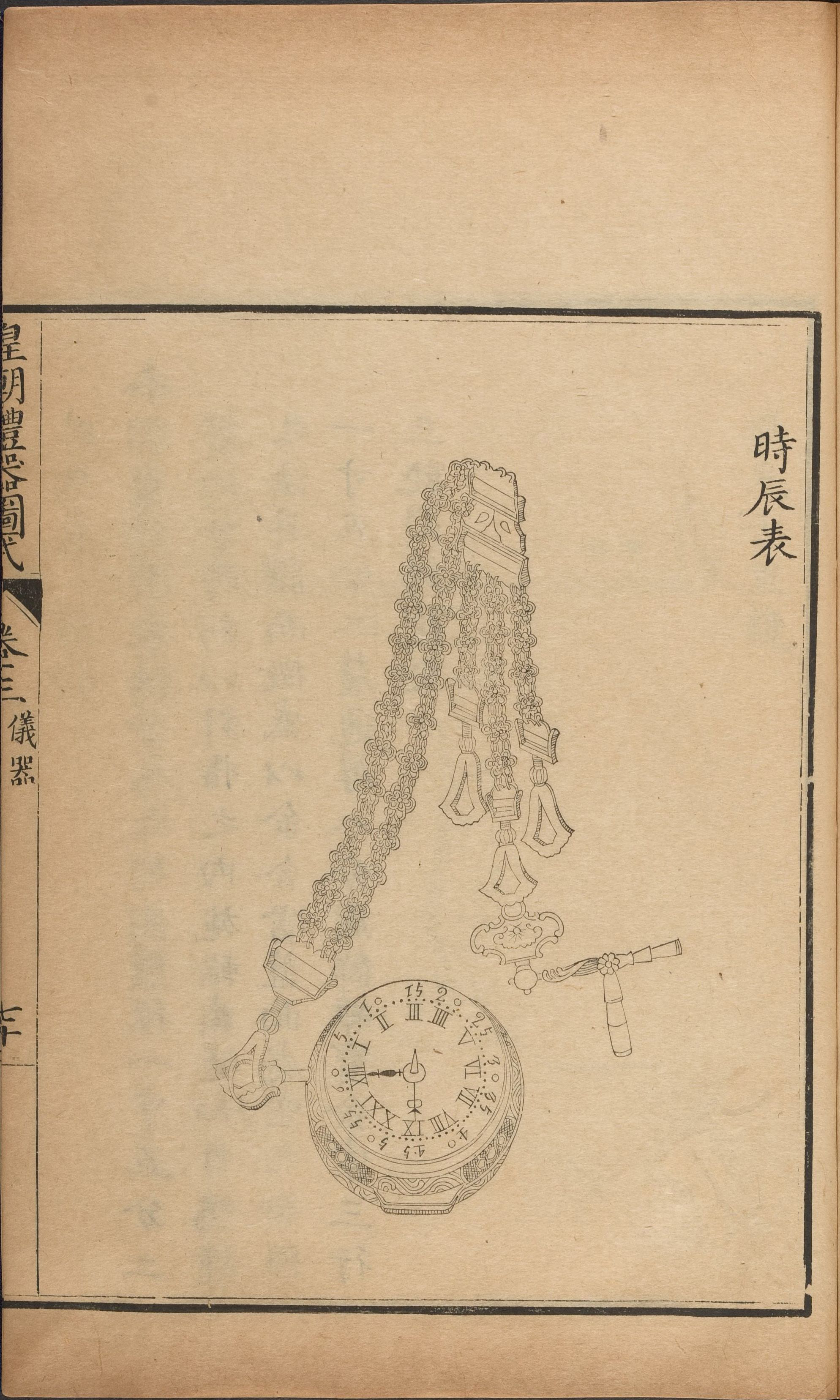

The "Twelve Beauties" painted by the court painter of the Yongzheng Dynasty depicts the furnishings very realistically. One of them, "Holding a Watch to a Chrysanthemum" (Picture 1), shows a beauty in ancient costume sitting on a table holding an enamel pocket watch. Pocket watches were called "hour watches" at the time. The pocket watch in the beauty's hand is a copper-cased enamel pocket watch, with Roman numerals marking the time. There are many pocket watches of similar style in the Qing palace. (Figure 2) The chronometer is not only used as a timekeeping tool, but also as a ritual instrument. It is included in the "Instruments" category of "Dynasty Ritual Utensil Schematics". (Picture 3) "Illustrations of Imperial Ritual Utensils" states that "this dynasty made a timetable, which was made of cast gold and was round in shape. The diameter of the disk was one inch and one-fifth of two centimeters, and the time was equally divided and pointed by a needle. There were gear teeth inside. Just like the method of ringing a bell, it is specific but subtle." It explains in detail the production process of the timetable of the Qianlong Dynasty.

Figure 1 "Holding a Watch to the Chrysanthemum" from the "Twelve Beauties" of the Qing Dynasty, unknown, scroll on silk, ink and color, 184cm vertical, 98cm wide, Palace Museum

Figure 2: Clear bronze gold-plated case inlaid with agate pocket watch from the Palace Museum

Figure 3 "Timetable" from the instrument volume of "Imperial Ritual Utensils" of the Qing Dynasty

From the "Holding a Watch to a Chrysanthemum", we can clearly see that the pocket watch in the beauty's hand points to 20 o'clock. Behind the beauty, there are banners with poems written in running script. Although the poem is signed to Dong Qichang, the content of the poem and the calligraphy style are different from Dong Qichang, and it should be written by Emperor Yongzheng. Among them are poems such as "Every time I pity the strange clock in a foreign land, it only ruins time with a few chimes", "I am afraid of seeing the word "Mandarin Duck" when checking books, and sigh at the passing of time while holding the clock in my hand. They express the sigh of the passing of time prompted by the sound of the clock.

There is also a picture in "Twelve Beauties" called "Twisting Beads and Watching Cats", which depicts a lady holding rosary beads and watching cats play. (Picture 4) On the high table behind the lady in the painting, there is a wooden tower-style self-ringing clock. (Figure 5) This self-ringing clock shows the typical appearance of clocks made in the Qianlong Dynasty palace. The painter of the Academy of Fine Arts accurately drew the hour hand pointing on the dial - 13:38.

Figure 4 "Twisting Pearls and Watching Cats" from the "Twelve Beauties" of the Qing Dynasty, unknown. Color on silk scroll, 184 cm long, 98 cm wide. Palace Museum

Figure 5 Qing Qianlong Dynasty red sandalwood tower-style hour clock, 100 cm high, 51 cm wide, 41 cm thick, Palace Museum

"Forty Scenes of the Old Summer Palace" is an album of royal gardens co-produced by the court painters Shen Yuan and Tang Dai of the Qianlong Dynasty. The "Ci Yun Protector" in "Forty Scenes of the Old Summer Palace" depicts a religious building directly north of the central axis of the Old Summer Palace, where many Buddhist and Taoist gods are enshrined. There is a three-story self-ringing bell tower built on the northwest side of Ciyun Puhu, with a copper golden phoenix flag on the top. On the south side of the second floor of the bell tower, there is a large self-ringing clock called the "Shishi Ruyi Hour Clock" with a "big caviar gold lacquer dial". Whenever the emperor visited the Old Summer Palace, he could hear the sound of the chiming clock on the hour. This bell tower, together with the Wenchang Pavilion Self-ringing Bell Tower in Qingyi Garden and the Luyunfang Self-ringing Bell Tower in Jingyi Garden, is known as the three major self-ringing bell towers in the royal gardens of the Qing Dynasty. The artist meticulously depicts the hands and Roman numerals on the dial of the clock tower - 7:40. (Picture 6) On the opposite page, there is a poem "Ciyun Puhu" written by Emperor Qianlong written by the poet Wang Youdun, which says: "There is a three-story building with carved clocks and clocks."

Figure 6 "Ci Yun Pu Fu" (detail) from "Forty Scenes of the Old Summer Palace" by Shen Yuan and Tang Dai of the Qing Dynasty, 64 cm in height and 65 cm in width, color on silk, Bibliothèque nationale de France

When the emperor went on tour, clocks were also very important accompanying items. Emperor Qianlong abided by the ancestral precepts of Manchuria, inherited the regulations of the previous dynasty, and held the Mulan Autumn Festival in August and September every year. Qing palace painters would also travel with them and paint paintings. "Hongli Weihu Captures a Deer" depicts the scene of Emperor Qianlong bending his bow and arrow and riding a horse to compete with deer in Mulan Paddock. (Picture 7) There was a concubine following him on horseback, handing an arrow to Emperor Qianlong. There are clocks inlaid in front of the saddle bridge where Emperor Qianlong and his concubines rode. Emperor Qianlong had many royal saddles with watch inlays. Horse saddles are usually stored in the North Anku, under the responsibility of the Armed Forces Academy. The clock on the saddle is dismantled and stored in the clock-making area for daily maintenance and repair, and then installed together when in use. In addition to this painting, there are also Qing palace paintings such as "Hongli Hunting Picture" and "Hongli Jinyun Good Horse Picture" depicting clocks on the saddle.

Figure 7 Anonymous Qing Dynasty "Hongli Weihu Captures a Deer", color on scroll paper, Palace Museum

Many Western clocks were brought into the palace by missionaries, and tribute clocks also appeared in the paintings of the Qing palace. The Qianlong Dynasty Painting Academy painted many paintings of "All Nations Coming to the Dynasty" under the instruction of Emperor Qianlong. These paintings are large in size and were completed by a number of painters from the art academy. After they were painted, they were hung in the bright windows of Yangxin Hall and Yangxing Hall. "The Picture of All Nations Coming to Korea" has a similar composition, showing the Forbidden City in a snowy winter scene from a bird's-eye perspective. The foreground focuses on the scene of the vassal states of the Qing Dynasty and foreign envoys entering the palace to pay their respects. Among them are envoys from Annan, Korea and other countries in Asia, as well as envoys from England, France and other countries on the other side of the ocean. They were carrying gifts and there was a lot of bustle and excitement. However, the scene shown in the picture of envoys from many countries coming to Beijing to worship has never really happened in history. "The Picture of the Coming of All Nations" is an ideal imperial image constructed by Emperor Qianlong in order to promote his political achievements. It is not a documentary painting, but it contains elements of historical truth.

In "The Picture of All Nations Coming to Korea" (Picture 8) in the 26th year of Qianlong's reign (1761), and in "The Picture of All Nations Coming to Korea" (Picture 9) in the forty-third year of Qianlong's reign (1778), many Western envoys are depicted holding various clocks and watches. I want to donate to Emperor Qianlong. In fact, clocks and watches not only represented a high level of craftsmanship but also aroused the emperor's interest. They were indeed the first choice gifts for Western diplomatic envoys. Russia has donated European clocks to Emperor Kangxi and Emperor Yongzheng many times. The British Macartney Mission who came to China during the Qianlong Dynasty chose an astronomical and geographical musical clock as a gift to the Qianlong Emperor. The British mission believes that this composite astronomical timepiece can not only report the month, date and hour at any time, but can also be used to understand the universe, and represents the latest progress in modern European science and technology.

Figure 8 Part of the clock scroll in "The Picture of the Coming of All Nations", ink and color on silk, 1761, Palace Museum

Figure 9 A part of a clock scroll from the Qing Dynasty's "The Picture of the Coming of All Nations", ink and color on silk, 1778, Palace Museum

Located in the northwest corner of the Ningshou Palace Garden in the Forbidden City, Juanqinzhai was built in the 38th year of Qianlong's reign (1773). It was originally used as a place for Emperor Qianlong to take care of himself after his abdication. The walls of Juanqinzhai are decorated with large-scale panoramic line paintings, which were created based on ceiling paintings in European churches. The landscape line painting was mainly painted by the Qing court painter Wang Youxue, leading the painters and students of the art academy, and has a visual illusion effect that makes it look real. The painting began in the 39th year of Qianlong's reign (1774) and lasted for five years. It was not completed until the end of the 44th year of Qianlong's reign (1779).

At the corner of the stairs on the second floor of the west hall of Juanqinzhai, there is a line drawing that is realistic enough to be true. It depicts a graceful woman with half-lifted door curtain. (Picture 10) Next to the beauty are several desks, books and other interior furnishings. There is also a Western self-ringing wall clock painted next to the door curtain. This Western self-ringing wall clock has a wooden casing, a carved wooden roof on the upper part, a round copper dial in the middle, and a gold-plated long round pendulum visible on the lower part. The decoration style of the entire wall clock has a Western style. There is no real object in the clock collection of the Qing Dynasty. It may have been designed and drawn by an artist based on Western materials. The hands on the dial of the wall clock were drawn by the academy artist and pointed accurately at 11:18.

Figure 10 The women in the four west rooms of Juanqinzhai lifted the curtains and put up paintings

In the late Qing Dynasty, clocks were still used as important timekeeping tools in court life and also appeared in late Qing court paintings. For example, in "The Picture of Empress Xiao Qinxian Playing Chess", the man playing chess with Empress Xiao Qinxian, the Empress Dowager Cixi, wears a pocket watch on his waist. This is the practice of wearing pocket watches by nobles in the late Qing Dynasty. Another example is the "Guangxu Wedding Album" which shows Emperor Guangxu marrying Queen Yehenara into the palace. One page of the "Queen's Dowry Picture" also depicts the four clocks included in the queen's natal dowry. It is said that when Emperor Guangxu got married, Queen Victoria of England even sent a chiming bell to celebrate. On both sides of the clock base are engraved couplets of congratulations on the wedding: "The sun and the moon will announce the twelve o'clock of the Ming Dynasty to bring good luck and good luck, and the heaven and earth will unite to celebrate hundreds of millions of years of prosperity and prosperity."

Whether it is the "Haixi Zhishicao" (Picture 11) written by Lang Shining, or the paintings of ladies such as "Holding a Watch to the Chrysanthemum" and "Watching a Cat Twisting Pearls" of the Yongzheng Dynasty, or the "Beauty Lifting the Curtain" in Juanqinzhai. These Qing palace paintings showing clocks, using the scenery line method, reflect that Western clocks were widely used in the Qing palace for their accuracy and convenience.

Figure 11 Qing Dynasty Lang Shining Haixi Zhishi Cao scroll on paper ink color 136.6 cm vertical 88.6 cm Taipei National Palace Museum

The combination of Chinese and Western time

Although the Qianlong Dynasty was a period of strong national power in the Qing Dynasty, the self-ringing clocks and pocket watches imported from the West were still precious luxuries at this time, which could only be enjoyed by the royal family and a few powerful people. The majority of the people have no chance to experience the convenience of timekeeping by clocks. The traditional Chinese twelve o'clock is still a widely used timekeeping method. Against this background, the Qing palace continued traditional timekeeping methods while using Western clocks and clocks.

Unlike Westerners, Chinese people do not regard time as a specific point in time, but tend to understand time as an opportunity, a season, and a process of time flowing. In Han culture, the four seasons are given great significance, and following the seasons has become the primary rule of agricultural production and political governance. Although the emperor of the Qing Dynasty was a Manchu, after entering the customs, due to his jurisdiction over a vast farming area, he also increasingly paid attention to the seasonal festivals that had a great impact on harvests. The farming festivals of the Central Plains were also integrated into the life of the Qing palace.

Dual timekeeping methods were used in the life of the Qing Dynasty, namely the Central Plains seasonal time and the Western minute and second timekeeping. Chinese and Western timekeeping methods each have their own scope of application and correspond to different governance needs: if you want to manage agriculture and control floods, you can use the traditional seasonal regulations of the Central Plains; if you want to keep accurate time and deal with Westerners, you can use the imported Western minute and second timers. . In the actual life of people in the Qing Dynasty, Chinese and Western timekeeping methods could be converted into each other and used side by side, reflecting the integration of Chinese and Western time.

The conversion and use of Chinese and Western timing methods can be seen in detail in the novel "A Dream of Red Mansions" written by Cao Xueqin in the Qing Dynasty. (Picture 12) Chapter 63 of "Dream of Red Mansions" tells that the sisters held a banquet for Baoyu's birthday. While they were enjoying themselves, Aunt Xue sent someone to take Daiyu back. Everyone asked what time it was. "The person replied: 'It's after the second watch, the clock has struck eleven.' Baoyu still didn't believe it, so he turned to his watch and took a look. It was already ten minutes after the first hour of the day." The "Zi Chu Chu Chu Chu Ten" here is a juxtaposition of Chinese and Western timing methods. "Zichuchuji" is the traditional timekeeping, while "Shifen" is the Western timekeeping. "Zi Chuchu is ten minutes" can be converted into 23 hours and 10 minutes. Although "A Dream of Red Mansions" is a novel, it can be seen from it that people at that time were already accustomed to the conversion of Chinese and Western timekeeping methods. Whether it is the "after the second watch" of traditional Chinese time, or the "clock strikes eleven" of Western timekeeping, or "the tenth hour of the first hour of the child", which need to be converted, the Qing people have already used it very well. Familiar.

Figure 12 Qing Dynasty Sun Wen's "Dream of Red Mansions" Chapter 25 on silk, ink and color, length 43.3 cm, width 76.5 cm, Lushun Museum

The coexistence of Chinese and Western timekeeping methods can also be seen from the display of timepieces in the Qing palace. Sundials were installed in front of many palaces in the Qing Palace. The scales on the sundial face are mostly ninety-six quarters, following the ninety-six-quarter day counting implemented after the Kangxi calendar reform, rather than the traditional Chinese hundred-quarter day counting. Although the sundial can measure the shadow of the sun to keep time, it no longer had a real timekeeping function in the Qing Dynasty, but had more symbolic meaning.

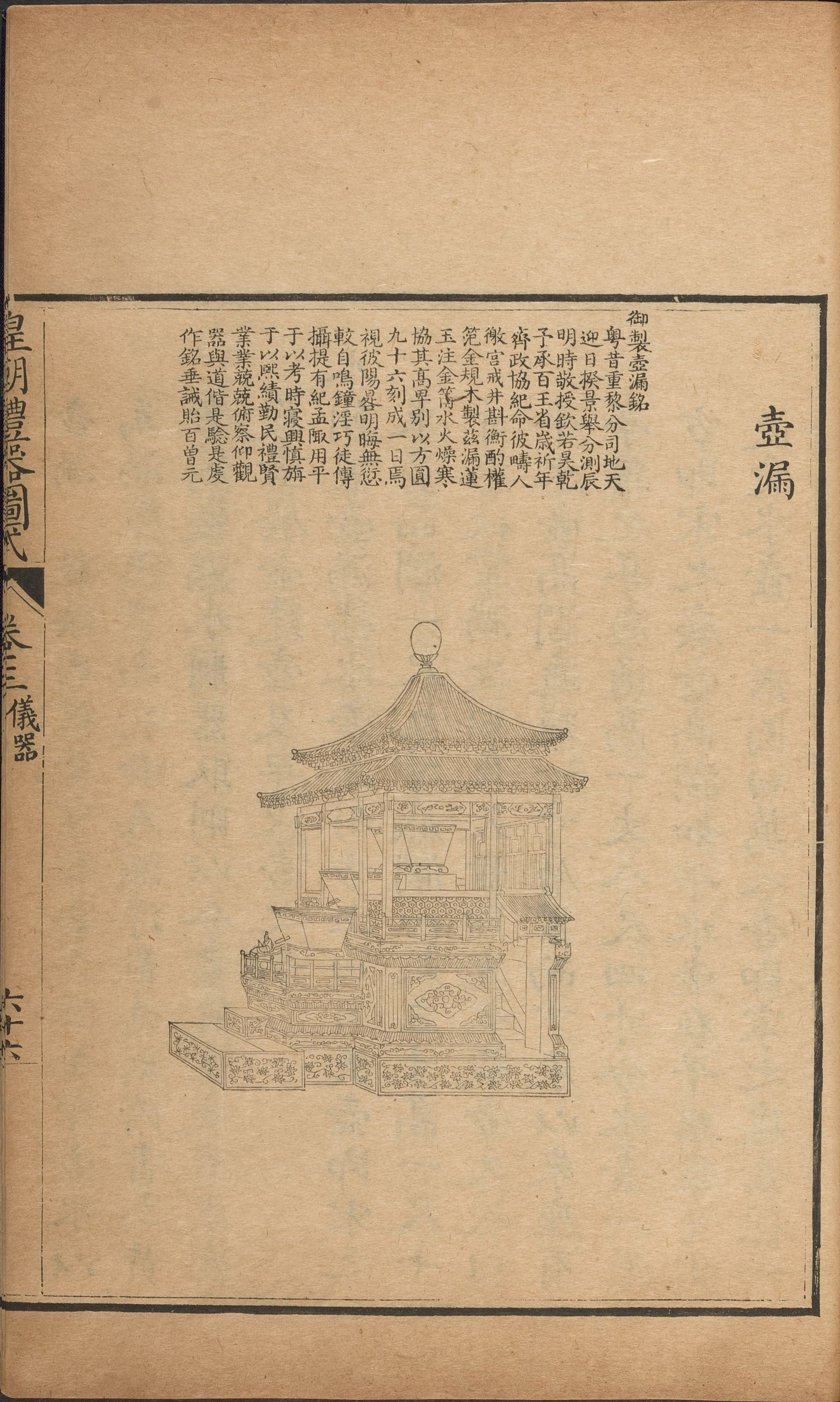

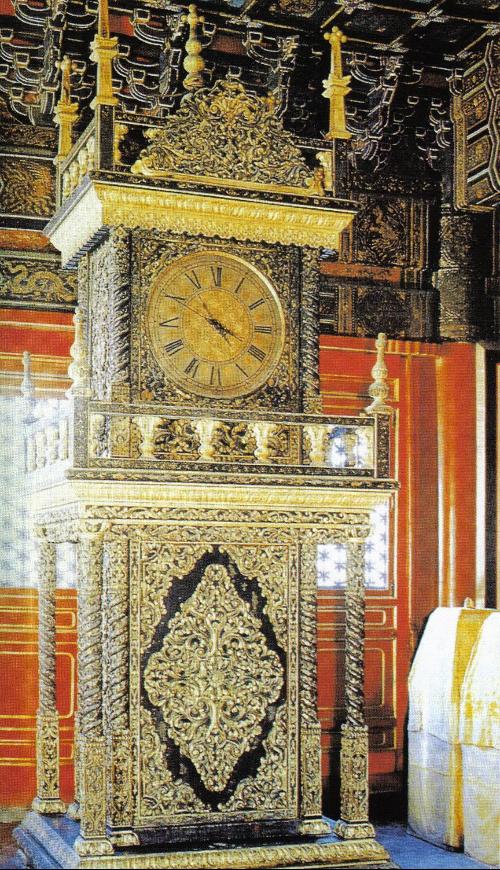

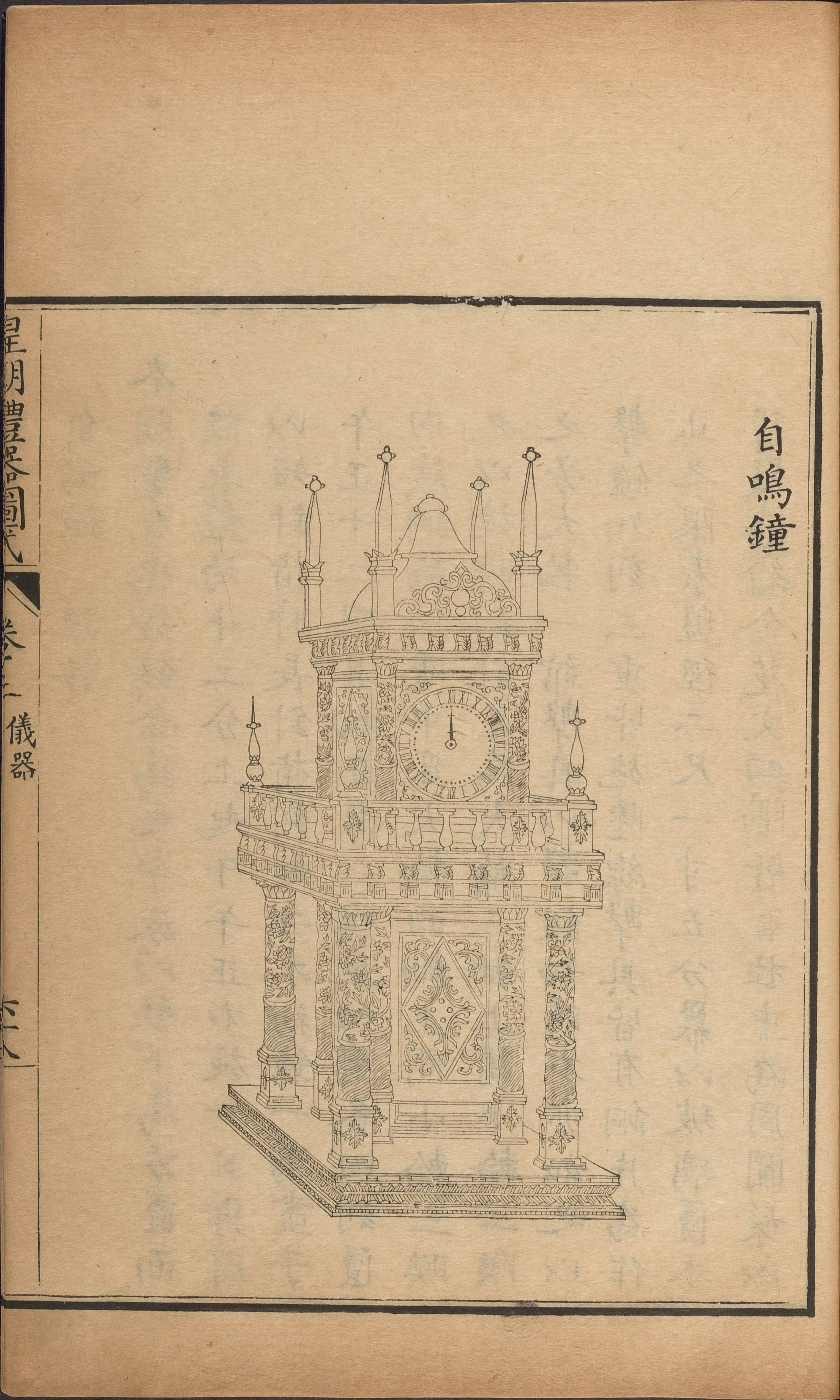

Jiaotai Palace is one of the three palaces in the inner court of the Qing Dynasty, located between Qianqing Palace and Kunning Palace. In the Jiaotai Hall, both Chinese and Western timekeeping tools are displayed (Figure 13). A traditional Chinese copper kettle dripper is installed in the east room. A large Western self-ringing bell is installed in the West Second Room. The copper kettle hourglass (Figure 14) is huge and was made in the 10th year of Qianlong's reign (1745). As a ritual vessel, it is included in the "Instruments" category of "Dynasty Ritual Vessel Schematics". (Picture 15) Emperor Qianlong once wrote the "Imperial Clepsydra Inscription" for him, saying that "ninety-six carvings make one day". Later, due to disrepair and inconvenience in keeping time, the copper kettle dripper was abandoned. The Grand Sonnerie Bell (Fig. 16), as a Western mechanical timekeeping device, is also included in the "Instrument" category of the "Dynasty Ritual Utensils" (Fig. 17). The big self-ringing bell is not only displayed in the Jiaotai Hall as a ceremonial symbol, but also has been in use because of its accurate timekeeping. The sound of its bell is loud and distant, reaching directly outside the Qianqing Gate. Ministers on duty in the palace need to rely on the large self-ringing clock in Jiaotai Palace to tell the time to calibrate whether the time of their pocket watches is accurate.

Figure 13 Interior view of Jiaotai Hall

Figure 14 Jiaotai Palace Copper Kettle Hourglass Palace Museum

Figure 15 "Ewer Leak" from the Instrument Volume of "Dynasty Ritual Utensils" of the Qing Dynasty

Figure 16 The black lacquered golden flower and wood tower of Jiaotai Hall and the self-ringing bell in the Palace Museum

Figure 17 "Self-ringing Bell" from the Instrument Volume of "Imperial Ritual Utensils" of the Qing Dynasty

Whether it is Castiglione's "Haixi Zhishicao" or the paintings of clocks by Qing palace painters, they all faithfully show the alternate application of Chinese and Western dual timekeeping methods in the life of the Qing palace at this time. This not only reflects the daily form of political rule of the Qing Dynasty, but also reflects its inclusiveness in Sino-Western exchanges to a certain extent.

book shadow

"Time Reflection in the Forbidden City: A Perspective on Qing Dynasty Palace Paintings" by Zhao Yanzhe, Guangxi Normal University Press