On the last day of this year's APEC meeting, November 17, local time, the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, USA, welcomed a special exhibition "The Heart of Zen", which displayed "Persimmon Pictures" ("Persimmon Pictures" ("Six Figures") by Mu Xi, a master of Chinese freehand painting and a painter of the Southern Song Dynasty). "Persimmon Picture") and its sister work "Li Picture". This is also the first time in hundreds of years since the 17th century that two paintings have left Daitokuji Ryukoin Temple in Kyoto, Japan.

Muxi has an important influence on the history of Chinese literati paintings and Zen paintings. Japanese writer Kawabata Yasunari, Japanese painter and essayist Higashiyama Kaii, and photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto all highly admire Muxi; Ming Dynasty calligraphers and painters Shen Zhou and Zhu Da (Bada Shanren) They are also affected by Muxi.

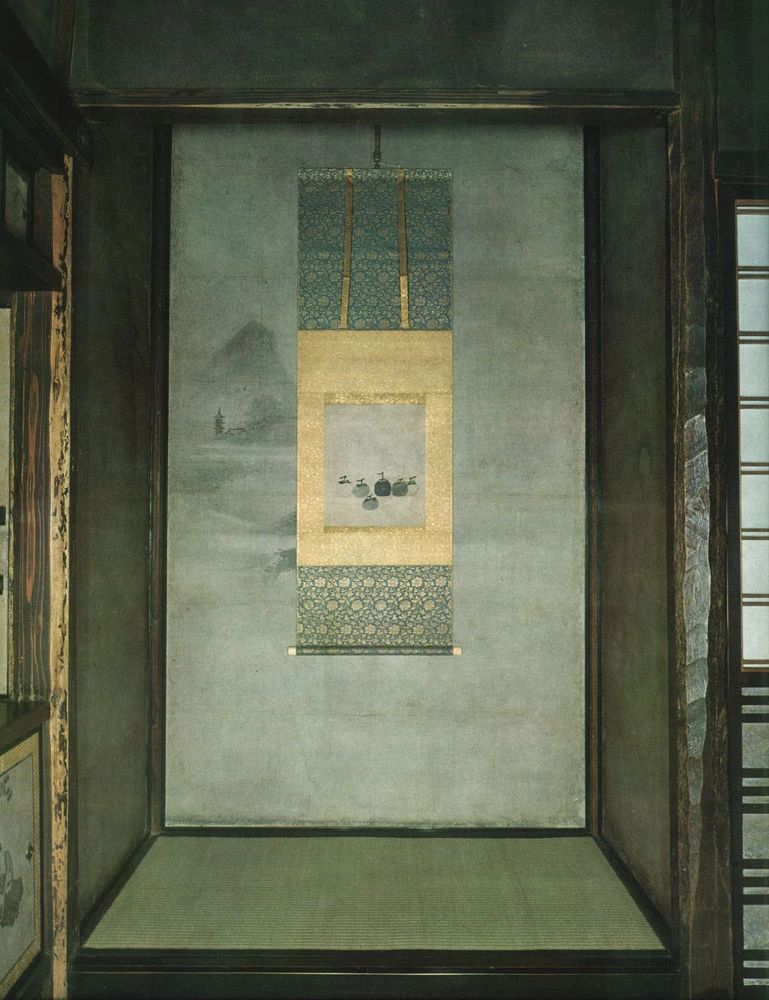

Exhibition view at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco by Kevin Candland

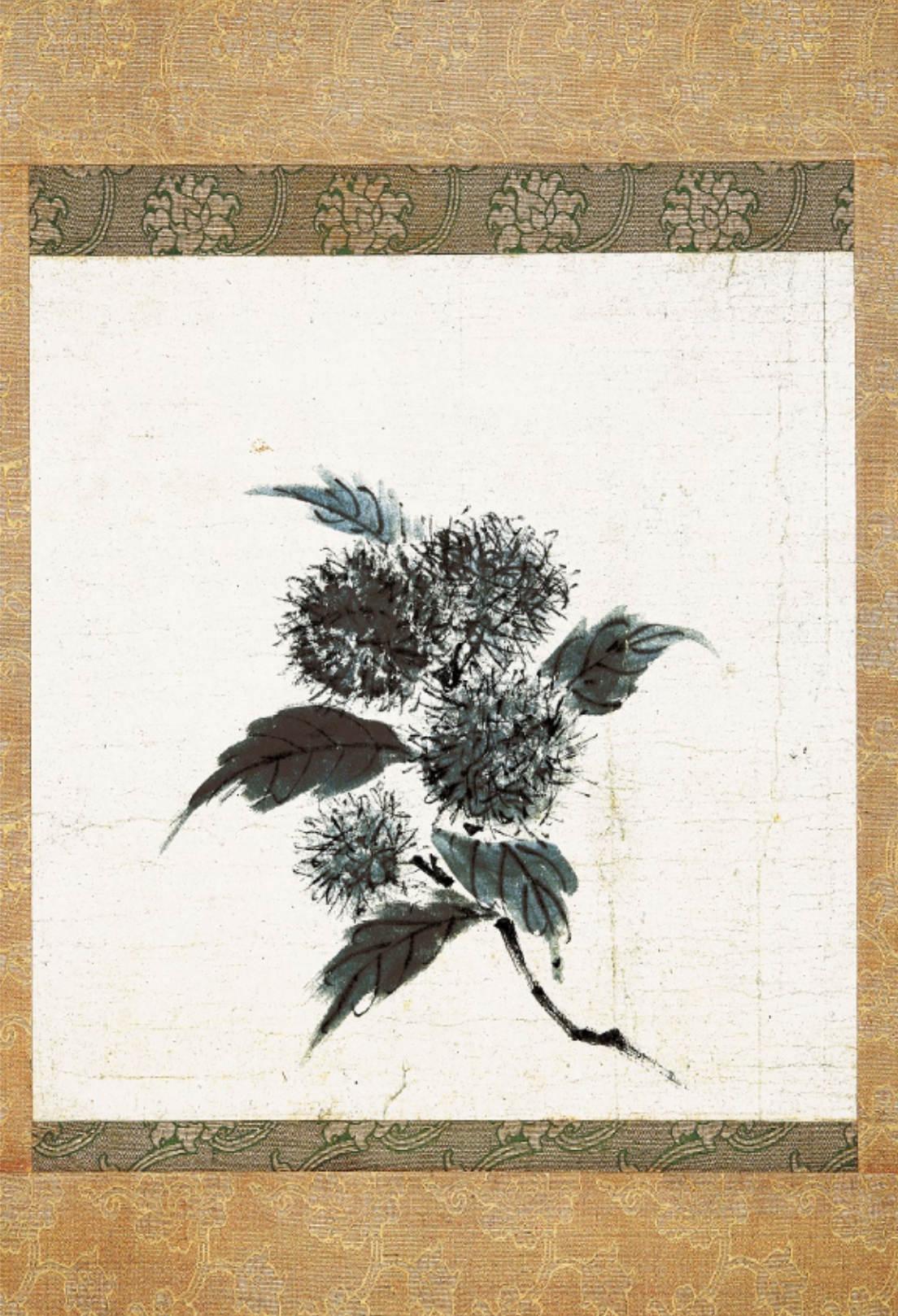

"Persimmon Picture", attributed to Mu Kei (China, active in the 13th century), vertical axis; ink on paper, from the collection of Daitokuji Ryukoin; Important Cultural Property; Image © Asian Art Museum, San Francisco

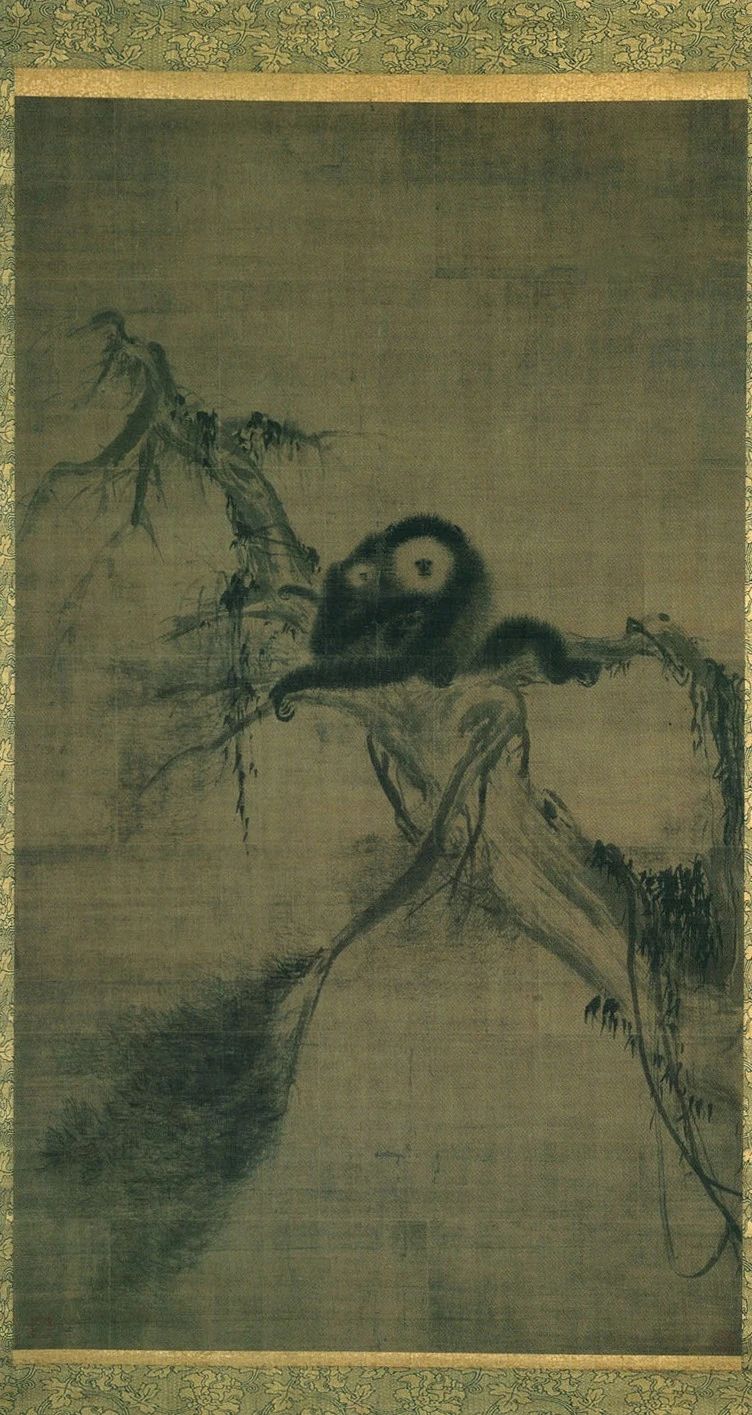

"Li Picture" (detail), attributed to Mu Kei (China, active in the 13th century), vertical axis; ink on paper, from the collection of Daitokuji Ryukoin; Important Cultural Property; Image © Asian Art Museum, San Francisco

Mu Xi was a Zen monk painter in the Southern Song Dynasty in China. His Buddhist name was Fa Chang. With his quiet, simple, unadorned and freehand style, he has great reputation and respect in the history of Chinese painting and Japan. He is known as "Japanese painting". A great benefactor of the Tao.” Mu Xi is also a mysterious figure. He is good at painting landscapes, fruits and vegetables, and freehand splash-ink monks and Taoist figures. Historical records about Muxi are unclear. Wu Dasu's "Songzhai Meipu" of the Yuan Dynasty has a relatively detailed description of this painter: "Seng Fachang, a native of Shu, named Muxi. He likes to paint dragons, tigers, apes and cranes, birds, landscapes, trees and rocks, and people. There is no coloring. The knots are mostly made of bagasse and grass, and they are all made with casual brushstrokes and ink. The meaning is simple and simple, and there is no need for decoration. The shapes of pine, bamboo, plum orchid stoneware are similar, and the writing on lotus and reed is both elegant."

Japanese writer Kawabata Yasunari is a fan of Mu Xi. He once said in a public speech in the 1970s: " Mu Xi was an early Zen monk in China and was not taken seriously in China. It seems that because his paintings are somewhat Some are rough and are almost not respected in the history of Chinese painting. However, they are greatly respected in Japan. Chinese painting theory does not highly praise Mu Xi. Of course, this view also came to Japan with Mu Xi's works. Although this The theory of painting has entered Japan, but Japan still regards Muxi as the highest. From this, we can get a glimpse of the difference between China and Japan... In Japan, there is Muxi's "Eight Scenes of Xiaoxiang", which is said to be written by Muxi. Is it true? We know that Daitoku-ji Temple, a Zen temple in Kyoto, contains the Sakyamuni Buddha, the Bamboo Crane, and the Shozaru, and these should be authentic."

For Japanese ink art, Muxi's paintings are a manifestation of the Zen spirit and also lead the "monk-like" ink style. What's more valuable is that Mu Xi's influence is not limited to Zen Buddhism, ink painting and the era in which he lived. The modern Japanese painter and essayist Higashiyama Kaii (1908-1999) highly praised Muxi: "Muxi's paintings have a strong atmosphere and are very realistic, but he contains these to form a humorous and soft expression. It is very interesting and very poetic. Therefore, it is the most suitable for the Japanese people's hobbies and the most suitable for the Japanese delicate sense. It can be said that in the Japanese customs, the true value of Muxi's paintings has been recognized. "

Higashiyama Kaii, "Green Sound", 1982. Image from: Shinano Art Museum, Nagano Prefecture, Higashiyama Kaii

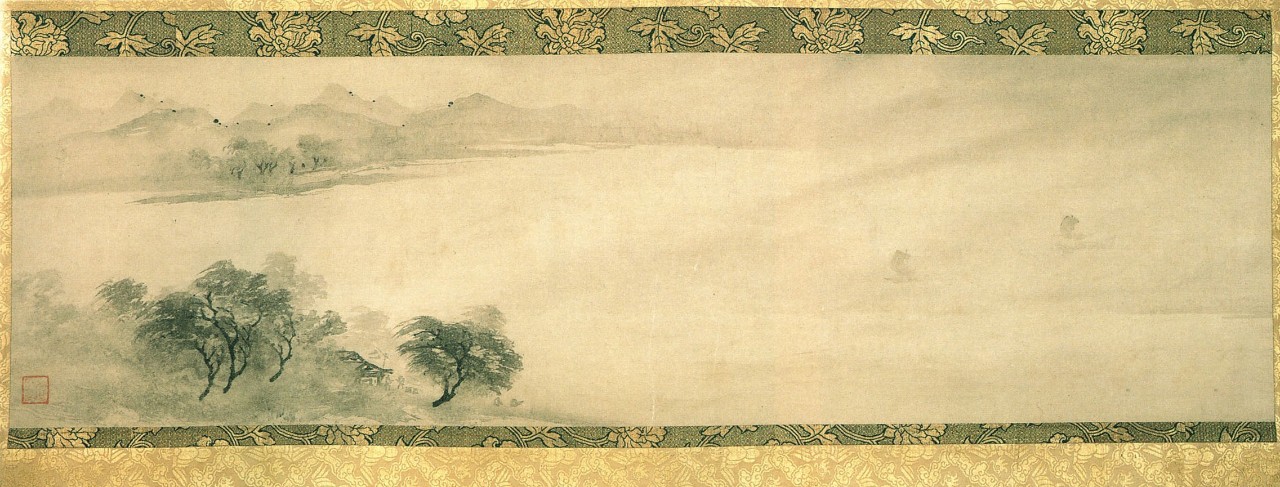

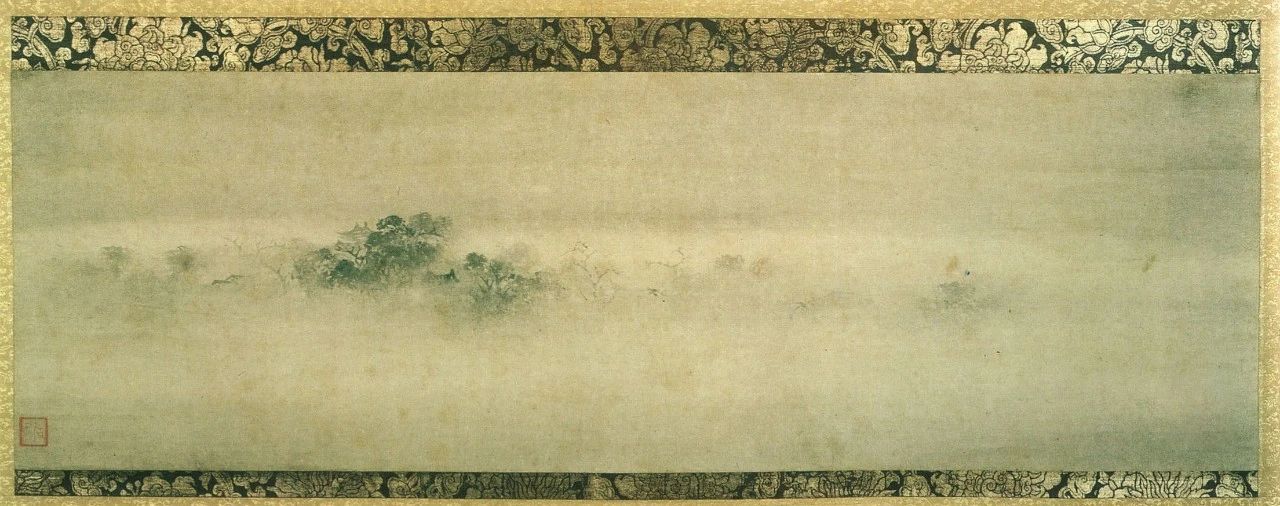

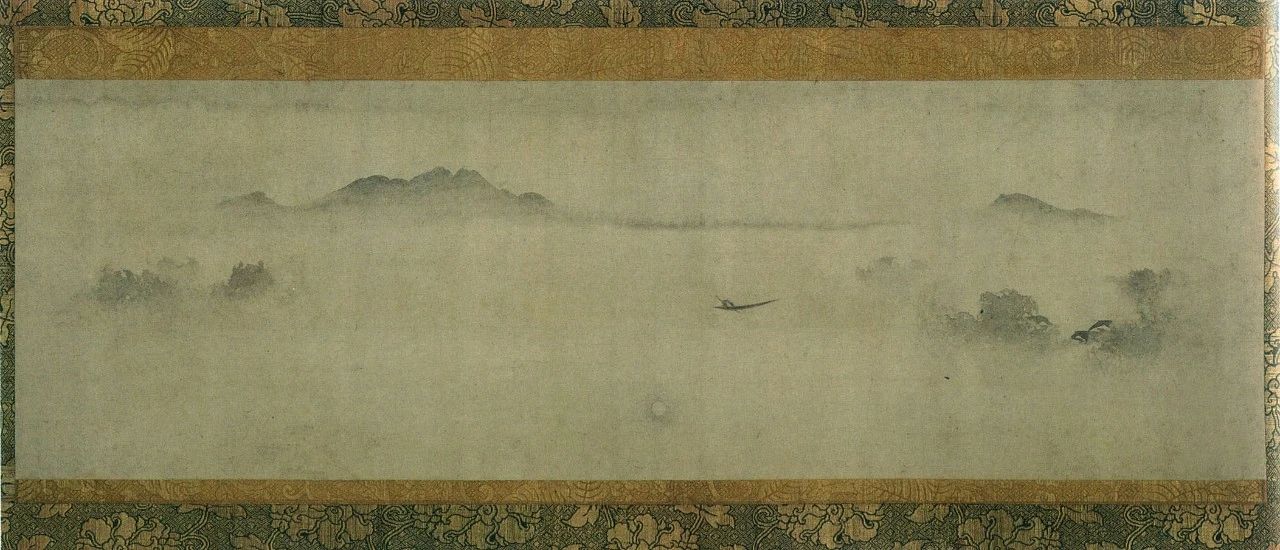

Contemporary artist and photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto (1948-) also commented on Muxi's "Eight Views of Xiaoxiang: Evening Bell of Yansi Temple": "...the whole picture is filled with steaming clouds and fog covering the surrounding areas, and the bells of Yansi Temple seem to be ringing in the air." It echoes in people's hearts for a long time. This painting uses visual enjoyment to guide the hearing, which is really rare in the world." He said, "I learned how to observe omitted details from Muxi's paintings.

Eight Scenes of Xiaoxiang·Guifan from Yuanpu

Eight Scenes of Xiaoxiang·Evening Bell of Yansi Temple

Eight Scenes of Xiaoxiang·Dongting Autumn Moon

Hiroshi Sugimoto, "Caribbean, Jamaica", 1980

© Hiroshi Sugimoto/Courtesy of Gallery Koyanagi

Not only the Japanese but also Americans are interested in Muxi. Ban Zonghua, a famous American scholar of Chinese art history, is quite fascinated by the mysterious Muxi. He once wrote an article recalling: "It has been half a century since I first saw Mu Xi's "Six Persimmons" when I was a student studying Chinese, but I have always been very curious about Mu Xi's paintings, and his works are among the I will continue to play the same role in my future research and teaching." "Six Persimmons" is also one of the reasons why Ban Zonghua entered Chinese art.

In the history of Chinese painting, he is the painter who has the greatest influence from China on Japan, and is the most loved and valued painter. He is even called the "great benefactor of Japanese painting". Since the beginning of the 17th century, the "Six Persimmons" and "Ritsu" have been hidden in Daitokuji Ryukoin, Kyoto, Japan. In 1919, these two masterpieces were designated as "Important Cultural Properties" of Japan.

These two works have rarely been exhibited in public. This exhibition is the first time in hundreds of years that these two treasures have left Japan and are only on display in Yabo. The last time the "Six Persimmons" and "Li" were publicly exhibited was in the spring of 2019 at the "Datetokuji Ryukoin National Treasures of the Sun-Changing Tenmu and Broken Straw Sandals" held by the Miho Art Museum in Shiga Prefecture, Japan. There are also Japanese national treasures such as "Yao Huan Tianmu".

“Persimmon” and “Chestnut” in Muxi

"Zen Heart" only exhibits two works, but their weight is enormous. "Six Persimmons" and "Li" are generally considered to have been painted by the Southern Song Dynasty painter Mu Xi. The former depicts six persimmons of different shades, while the latter depicts four chestnuts still with burrs. These fruits seem to be light. The spiritual place emerges from the empty background. The artist uses different ink tones and presents fruits and leaves with simple and vivid brushstrokes, injecting simple and elegant charm into these ordinary natural objects, making them fascinating objects.

The reason these two paintings are so important in Japan is that for Japanese people living in the Middle Ages and early modern times, the name "Muxi" was almost synonymous with Chinese-style painting (kara-e). His Zen-like painting style was particularly popular with the Zen aesthetics that was emerging in Japan at the time. In Japan, Muxi has had a profound influence on the painting world and even the cultural and artistic circles. The Kanō school, a mainstream painting school with an important position in the history of Japanese classical painting, is one of the important inheritances of Muxi's painting style.

On the contrary, in China, Muxi's popularity is slightly weak. For the Chinese painting school that focused on grandeur at that time, Mu Xi's highly abstract painting style was popular during the Song and Yuan Dynasties, but it did not have a high reputation in the mainstream evaluation system. The authentic Muxi paintings that have been preserved in China are even rarer.

From Daitokuji Rikoin Temple in Kyoto to Asian Art Museum in San Francisco

The "Six Persimmons" and "Likuri" were painted by Mu Kei in China. They may have originally been part of a hand scroll. In the 15th century, it was said that they were reframed as hanging scrolls in Japan. For centuries, both paintings have been in the collection of Daitokuji Ryuko-in, a famous Zen temple in Kyoto. In 1919, the Japanese government designated these two paintings as Japan's "Important Cultural Properties."

Daitoku-ji Temple, to which Ryuko-in belongs, is one of the Zen cultural centers founded in the Kamakura period.

Daitokuji Ryukoin, a famous Zen temple in Kyoto

"Six Persimmons" in Daitoku-ji Temple Ryoko-in Temple, Kyoto

While each of the museum's international loan exhibitions aims to promote international peace and intercultural understanding, "The Zen Heart" also has a uniquely personal dimension. In 2017, Kobori Geppo, the abbot of Daitokuji Rikoin Temple, visited the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco and also toured the city. He had deep sympathy for the disadvantaged groups in the Bay Area. So he came up with the idea of sharing this pair of treasures with the world in San Francisco to arouse people's compassion and promote peace and harmony. Thanks to Ryokoin's generosity, looking at Muxi's work may bring a moment of tranquility at a time when people have to deal with the hardships and hardships of daily life.

What are the differences between Chinese and Japanese evaluations of Muxi?

According to Wu Dashu's records at the time: "The remaining relics of the scholar-bureaucrats in the south of the Yangtze River today have few bamboos and many fake reeds and wild geese." It can be seen that Muxi's paintings were very popular in the society at that time, so that fakes appeared.

However, in the mainstream painting circles at that time, people in the industry did not think highly of him. Zhuang Su, a theorist of calligraphy and painting in the Yuan Dynasty, said in the "Supplement to the Paintings": "It is not an elegant play. It can only be used in monks' rooms and Taoist houses to help quiet ears." Tang Wei, a connoisseur of calligraphy and painting in the Yuan Dynasty, commented in "Hua Jian": "In recent times, monks in Muxi often use ink bamboo, which is crude and evil and has no ancient method."

The reason is mainly because the painting school popular in the Song Dynasty at that time focused on realism and respected meticulous brushwork. The difference can be seen if compared with the paintings of Ma Yuan (1160-1225), who was recognized as the most accomplished painter at the time.

During the Southern Song Dynasty, Zen Buddhism became popular in China. Many monks from Japanese Zen Buddhism and other sects went to famous temples in southern China to seek Dharma. Among them was Yuan Er Bian Yuan (1208-1280), who was said to be a disciple of Master Wuzhun along with Mu Xi. . Later, when Enji returned to China, he brought back Muxi's "Ape and Crane Picture" (now stored in Daitokuji Temple). This was probably the first Muxi painting introduced to Japan. Enji Benen later founded Tofukuji Temple and became the first "national teacher" in the history of Japanese Buddhism. It was in his era that the political status of Japanese Zen was established.

Mu Xi's "Ape Picture"

When Mu Xi's paintings were introduced to Japan with the increasingly close Sino-Japanese trade and monks' exchanges, the ethereal Zen charm in them was especially sought after by Japanese Zen Buddhism, which in turn influenced the Japanese ink painting style. The painting styles of many Japanese painters are called "Muxi-like" and "Monk-like". Muxi's works are an important part of the influence of Zen Buddhism on Japanese aesthetics.

In the earliest catalog of collections of Song and Yuan paintings spread in Japan, "Catalog of Public Properties of Buddha's Temple: Enjueji Collection", as a top gift, Muxi's name is with Song Huizong. In the hands of General Ashikaga Yoshimasa (1436-1490), the leader of the Higashiyama Culture period, there are 279 Chinese paintings in the collection, 40% of which are works by Maki.

In China, as the times progress, people's attitudes towards Mu Xi's works are also changing. Shen Zhou, a famous calligrapher and painter in the Ming Dynasty, admired Mu Xi. He wrote a postscript to the "Ink Sketches" written for Mu Xi and praised his works "without applying color, just splashing ink at will, as if they were alive. Looking back at the likes of Huang Quan and Shun Ju, they are so charming." It’s down.” Bada Shanren's paintings were also deeply influenced by Muxi.

Shen Zhou's "Mohe Tu"

Mu Xi's "Ink Lotus Picture"

However, to this day, because the number of Muxi's works in China is small and the authenticity is doubtful, but the number of extant works in Japan is relatively large, and they have been well protected and studied, so when talking about "Muxi", in Japanese ink painting The weight in Jie's heart is still like that of a saint.

Exhibition site photography by Kevin Candland

The exhibition periods are from November 17th to December 10th and December 8th to 31st respectively, and the two works will be briefly displayed at the same time from December 8th to December 10th.