When we imagine the characters at Henry VIII's court, the work of Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/8-1543) almost always comes to mind. Just like the works of Thomas More (English politician, writer, philosopher) and Thomas Cromwell (Thomas Cromwell, British politician, trusted minister of King Henry VIII) in the Frick Collection in New York Portraits are like this for everyone in Holbein's works. With a shallow outline, we meet each living person, as if five hundred years have just passed in a blink of an eye.

The Paper has learned that the exhibition "Holbein at the Tudor Court" currently being held at the Queen's Gallery in London integrates Holbein's drawings and paintings, including 40 sketches of figures, which form the majority of this exquisite exhibition. The content and the basis of the painting - his eye captured the words and his hand drew the beautiful clear lines, presenting a vivid portrait of 16th century life. Like any good Tudor story, it begins with war and marriage, hiding endless drama and intrigue.

View of the exhibition "Holbein at the Tudor Court" at the Queen's Gallery

The sketches are so light and soft; the pastels barely press onto the paper. The lips are a mist of peach and pink, and the eyes are soft blues and grays. The focus on faces makes them feel closer to life and closer to reality. Although the thick and rough clothes seemed to hide his face in dark clouds.

Holbein, "Sketch for the Portrait of Sir Thomas More"

Compared to Holbein's unforgettable oil portraits, the preparatory sketches he never intended to exhibit were more "live". Thomas More's face with black stubble showed a gentle smile. This person feels like meeting this Renaissance thinker; another sketch of a larger portrait of Thomas More's family. Although the corresponding oil painting has been lost, the sketch takes you back five centuries and with this family. Spend time together.

Holbein, Sketches of Thomas More's Family Portrait, circa 1527

Thomas More was one of the leading figures of the Northern Renaissance and Holbein's first official patron. In 1526, Holbein, who was about 29 years old, came to Thomas More's home on the banks of the Chelsea River with a letter of recommendation from the famous theologian Erasmus. From then on, he spent most of his career in London. Pass. He worked his way to the top of British society, painting aristocrats, lawyers, politicians, soldiers, and eventually the king.

Holbein, Portrait of Sir Thomas More, 1527, Frick Collection, New York (not included in this exhibition)

Subtle changes in Holbein's style: still exciting but not soulful

Holbein painted the Tudor courtiers against a dark blue background, meticulously depicting their jewelry, furs, and pets. He based these paintings on sketches from life, many of which are preserved in the Royal Library. They are so precise and cold, like photographs. "I am a camera with the shutter open, recording quietly without thinking." Christopher Isherwood's narrative in "Goodbye to Berlin" seems to be describing Holbein in the Tudor Dynasty.

Born into an artistic family in Augsburg, Bavaria, Holbein began his career initially in Basel (the center of publishing and thought during the Over-Rhine Renaissance) before moving to England to specialize in portraiture.

Holbein, "Sketch for Portrait of Anne Cresac"

In Holbein's painting, Anne Cresacre, More's daughter-in-law, looks into the distance with gray-blue eyes, full of dreams; in another painting, Jane Seymour (Henry VIII) The third queen, and the only one who gave birth to his longed-for son), seemed a little depressed because she had to remain still in front of Holbein's "lens".

Holbein's "Portrait of Jane Seymour"

The portraits do seem to have the objectivity of photographs. In his book Secret Knowledge, David Hockney argued that Renaissance artists used early forms of cameras to capture lifelike images. Renaissance artists were not "secret" about their innovative techniques. Dürer published illustrations of how to use the mechanism of perspective to construct space, and Leonardo da Vinci described the camera obscura without suggesting that it had any artistic use.

Yet if any Renaissance portrait truly looks like photography? That belongs to Holbein. In the adjoining gallery, preparatory sketches for More's portrait are displayed on both sides, the reverse showing the fine needle marks that follow the lines of Holbein's painting. Technical analysis shows that Holbein would have driven a dowel through another sheet of paper underneath and used charcoal to transfer the outline through the holes to the canvas. Of course, in order to receive lucrative commissions, he first had to shock models with his painting science. This is why most of his sketches are artfully colored.

Holbein, Mrs. Vaux, circa 1535

Get into position and remain still. Holbein then painted some warm tones over the sketch. Models must feel amazing when they see themselves come alive on paper.

Holbein also painted pocket-sized portraits, which were often carried around as symbols of love or fidelity. From jewelry to hair, these miniature portraits boast incredible detail. How did he make such complex observations and depictions on such a tiny scale? He must have used optical equipment, probably similar to a jeweler's glasses.

Holbein, Miniature Portrait of a Lady, possibly Catherine Howard (wife of Henry VIII's fifth marriage and cousin of Anne Boleyn)

However, no matter how he did it, his intention was definitely to surprise. Holbein came to England because the religious reform in Switzerland at that time opposed the hanging of paintings and other icons in churches. As an artist, Holbein was in a difficult situation. It is known that he painted altarpieces, allegorical paintings, murals for Basel City Hall, and designed glass mosaics and decorative paintings for churches and private residences. But in Tudor England, portraiture was a simple, universal and irresistible genre and form that could transcend language barriers. Holbein included notes on his paintings: early on he wrote exclusively in German; later, gradually English words were added.

Holbein, "Henry Brandon" (miniature)

Engraved on the table beneath Henry Brandon's elbow was his age - five years. This is one of Holbein's few portraits of children and was probably commissioned by Henry's parents, who were among the most powerful figures at the Tudor court.

However, as he learned more about the unfamiliar country of England, his art became increasingly conservative—the more he learned about the Tudor court, the more he hid himself. The exhibition's drawings bear this out.

Holbein's first portraits painted in London and his studies of Thomas More and his family left a lasting impression. John More (son of Thomas) was probably in his father's library, engrossed in a book, his shaggy brown hair falling from his flat cap. Perhaps as he read, Holbein sketched clearly, quickly and loosely—John's clothes were captured as striped symbols, a vivid moment.

Holbein, "Portrait of John More"

Not that Holbein's later works were any less vivid. For example, when painting Jane Seymour, there was the pressure of a formal royal portrait, but her eyes were vibrant and her dimples human. Yet the shift, while subtle, is noticeable.

Holbein portrayed More and his family as friends of friends, and his later portraits of the courtiers were equally brilliant but less affectionate. The model posed more formally and Holbein looked at the model more closely. The poet Thomas Wyatt has a plump, broad face behind his black beard, his eyes looking sideways. Wyatt looked alert, and Holbein looked at him as if he were a still life, a specimen. But why the look of horror? In one poem, Wyatt warned to beware of the court, for "circa Regna tonat" - "thunder rolls around the throne".

Holbein, "Thomas Wyatt"

The thunder started when Henry VIII wanted to divorce his wife Catherine of Aragon and marry Anne Boleyn. The Pope's delay in granting divorce led to the English Reformation, followed by decades of death and paranoia. Wyatt was arrested on suspicion of liaison with Anne Boleyn, narrowly escaped arrest and may have witnessed her execution from a prison window in the Tower of London.

Holbein, Anne Boleyn (One of the few contemporary portraits of Henry VIII's wife from his second marriage, Anne wears an informal gown, possibly a gift from Henry. This The painting was completed without a corresponding portrait.)

Holbein came to London to escape the anti-artistic attitudes of the Reformation, but London was even more difficult for him, and his later portraits were scrupulously objective compared with his friendly depictions of the More family. He captures faces with a precision that takes your breath away, while avoiding getting too close to the subject he depicts.

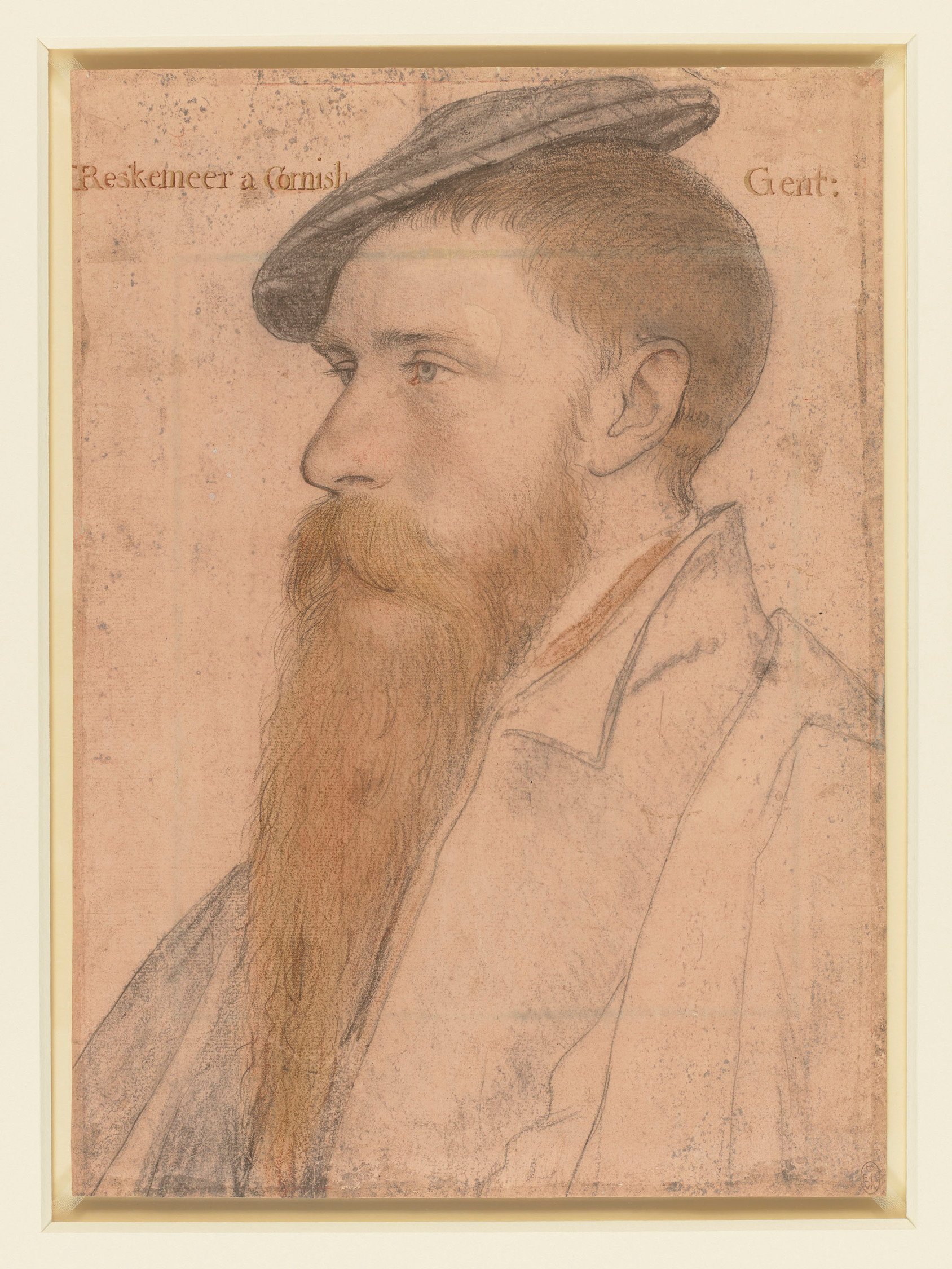

Holbein, William Reskimer (who held several minor positions at the court of Henry VIII); the painting depicts him with a long red beard, On the background of vines.

Holbein, "Sketches of William Reskimer." A comparison of sketches and paintings shows how closely Holbein followed the drawings in his finished work.

Between oil paintings and sketches, the meticulous refinement of images

In the painting section, Johannes Froben, stripped of the fashions of the time and sitting sullenly against a plain blue wall, looks nothing like a 16th-century printer. In Holbein's portrait, he could be anyone at any time. He looks to the left, his hair is sparse, his cheeks are droopy, his skin is yellow, and his arms are tucked into a black coat. He is so desolate and quiet, sad and heavy.

Holbein, "Johannes Froben"

However, Holbein's paintings, which correspond to the sketches, are now widely distributed in European and American collections. For example, a portrait of More in red velvet sleeves in front of a dramatic green curtain faces off against a portrait of Thomas Cromwell sitting primly at his writing desk in the Frick Collection in New York. Holbein's works are also collected in art galleries in Florence, Madrid, and Vienna. In addition, the National Gallery also has four important works by Holbein, including his portrait of Erasmus. None of these works appear in the exhibition. Under normal circumstances, the Queen's Gallery does not borrow exhibitions from other institutions. Thus, the portrait of Thomas More was presented as a photograph in addition to a prepared drawing, and the portrait of Holbein was exhibited as an inferior copy by another artist.

Even those works that survived the turmoil of their own time did not survive the next five centuries. The full-length portraits of Henry VIII and his third wife Jane Seymour on the wall of Whitehall Privy Council were destroyed in a fire in 1698, and only copies remain. In addition to direct reproductions, there are also high imitations here that use Holbein's portraits as the original images.

This portrait of Henry VIII is an early copy of Holbein's original. The original painting was painted in 1537 on the wall of the Privy Council at Whitehall Palace in London, which was destroyed by fire in 1698. This portrait was probably painted during the lifetime of Henry VIII and is still close to Holbein in technique.

But in any case, the exhibition shows life in the 16th century vividly. Thomas Lestrange with dreamy eyes and elegant manners in a high-collared shirt, exuberant Mary Shelton, tired Archbishop Warham; Richard · Richard Southwell is arrogant, Lady Ratcliffe stares intently at the audience, and Henry Guildford is rebellious and heavy.

Holbein, Henry Guildford, 1527

A mysterious painting attributed to Charles Wingfield shows a bald young man wearing nothing but a medal, and the artist carefully painted his chest hair. Prince Edward, as plump as his father, Anne Boleyn, Jane Seymour and the young Princess Mary emerged as real people in their own time.

Holbein, "Mary Sheldon" (cousin of Anne Boleyn, who later married Anthony Heveningham)

This is one of Holbein's most detailed sketches, and he paid special attention to the facial features, using small lines to indicate the shape of the nose. White is used to bring out Sheldon's eyes and the pearls on the pendant around her neck.

The few portraits are heavily framed with gold, and the subjects' dark cloaks and pale skin contrast sharply with the jewel-like greens and blues of the background. Thomas Howard looks determined (albeit tired) in spotted lynx fur. Derich Born, a handsome businessman, looked at us majestically. His painting bears the inscription: "If you add a voice, it would be Derich himself."

Holbein, "Portrait of Drich Byrne"

But the real thing to appreciate is to see Holbein, whose work inspired subsequent generations of court painters. How did he create images that have survived through the centuries? The pieces still look modern in a way.

Previously attributed to the 16th-century Flemish School, Elizabeth I as Princess

This painting is the most beautiful and striking portrait of Elizabeth I before she became Queen. Some believe that the painter of this work was William Scrots, an artist from the Netherlands who was employed by Henry VIII from 1545.

Note: The exhibition will last until April 14, 2024. This article is compiled from the Guardian, Daily Standard, inews and the Queen's Gallery website.