During the Eastern Han Dynasty, cemetery stone carvings gradually flourished, which are generally reflected in the following four aspects: first, several roughly fixed shapes were formed within various types of stone carvings; second, a basically stable spatial configuration pattern was formed; third, five distinct shapes were formed. Characteristic distribution areas; fourth, the user class is relatively wide. However, if we further analyze the political situation in the late Eastern Han Dynasty, the essence of the prosperity of stone carvings on mausoleums can be said to be a special trend of local forces showing off their power.

When the practice of setting up stone carvings in tomb areas began is still a controversial issue in academic circles. But what is clear is that both the "Qilin Stone Qilin" from the Mausoleum of the First Emperor of Qin, which only exists in later literature, and the group of stone carvings from the tomb of Huo Qubing in the Western Han Dynasty, which have attracted much attention from academic circles, were both "high-pitched and reclusive" in their respective eras, and they do not represent the general situation at that time. Burial customs. The situation was different during the Eastern Han Dynasty, when stone carvings began to become an important part of the tomb floor structure. This article intends to analyze the shape, age, spatial configuration, regional distribution and hierarchy of stone carvings in Eastern Han Dynasty cemeteries, and based on this, explore the political significance behind the prevalence of stone carvings in graveyards. If the judgment is inappropriate, I pray that the academic community will correct me.

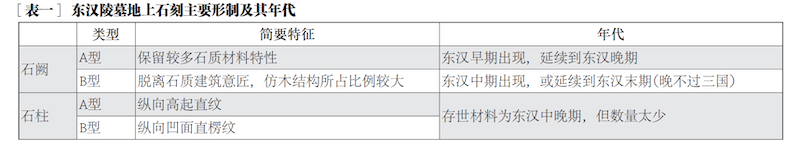

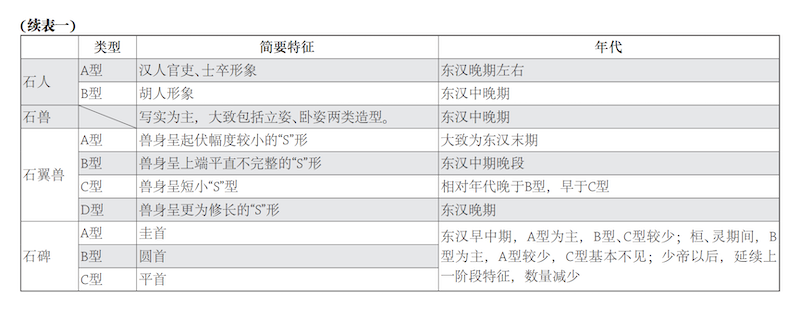

1. Main forms and popular eras

There are many types of stone carvings in Eastern Han dynasty cemeteries, including stone towers, stone pillars, stone figures, stone beasts, stone winged beasts, stone tablets, etc. Several relatively fixed shapes have been formed inside various types of stone carvings. Here is an overview of the main shapes of several types of stone carvings and their popularity.

1. Stone Tower

The stone tomb palace is a simulation of the wooden gates of real palaces and residences. Therefore, its structure is often imitated by wooden buildings. It is common to have relief columns, squares, and brackets on the base and body of the palace, and the upper part is covered with a roof. Further reference can be made to Mr. Chen Mingda's "Stone Palaces in the Han Dynasty" (hereinafter referred to as "Han Dynasty"). According to the degree of imitation of wooden structures, stone towers are divided into two types, A and B.

Type A retains more of the characteristics of the stone material as a whole. It only carves the roof into an imitation wood structure roof, and the more complicated ones only carve brackets under the roof. Jiaxiang Wu's Palace (Figure 1:1), Pingyi Huangshengqing Palace and Gongcao Palace belong to this type.

[Figure 1] Examples of stone towers in the Eastern Han Dynasty

1. Wushi Que in Jiaxiang Photographed by the author

2. Gao Yi Que in Ya'an, taken from Gao Ziqi's "Qin and Han Que", PhD thesis of Xi'an Academy of Fine Arts, 2013, page 113

3. Wangjiaping Que in Qu County, taken from "Qin and Han Que" by Gao Ziqi, page 86

Type B, separated from the stone architectural style, has a larger proportion of imitation wood structures. It is common to build multiple layers of stones between the roof cover and the body of the tower, and then carve out wooden-like structures such as rafters, buckets, and brackets, which can be called towers. Most of the stone towers in Sichuan area fall into this category. Some scholars further divide them into four forms based on the architectural form of imitation wood structures. This article will not go into details here.

In terms of age, A-type stone towers have appeared in the early Eastern Han Dynasty. The Huangshengqing Tower in the second year of Yuanhe (86) and the Gongcao Tower in the first year of Zhanghe (87) can be used as evidence. At the same time, they continued at least until the construction of Wushi Tower. The first year of Jianhe (147). Among Type B, "Han Que" research shows that Feng Huan Que was built in the first year of Jianguang (121). It is one of the earliest Type B Ques, so the upper limit of the age of this type should be in the middle of the Eastern Han Dynasty. The Gao Yi Que built in the 14th year of Jian'an (209) is the latest example among those with clear dates (Figure 1:2), so the lower limit of type B stone castles is at least the late Eastern Han Dynasty. "Han Que" believes that the Zhaojiaping Two Ques and Wangjiaping Ques in Qu County [Figure 1: 3] and the Three Ques date from as late as the Western Jin Dynasty. Mr. Liu Dunzhen also holds a similar view. Mr. Sun Hua conducted a more detailed group discussion on the six-que structure in Quxian County and believed that the above-mentioned three-que structure was popular in the late Eastern Han Dynasty, no later than the Shu Han Dynasty. Taken together, Mr. Sun Hua’s research should be the correct one.

2. Stone pillar

The complete stone column structure should include three parts: the top plate, the column body, and the base. The bases of the Eastern Han Dynasty stone pillars are basically undiscovered and will not be considered for the time being. The shape of the top plate, according to the actual objects seen in Xia Li Village, Ye County, Henan Province, should be a disk shape with a small stone-winged beast on top. The shape of the pillar body can be divided into two types according to the different patterns:

Type A, the main body of the column is decorated with a vertical "high straight pattern", with a rope pattern on the top and bottom, which should be the "bamboo cross pattern" seen in the literature. One surviving example is the Shinto stone pillar of Langxiexiang Liujun in Jinan (Figure 2:1). Part of the stone forehead remains. The three characters "Xiexiang Liu" can be seen, and two animals are decorated on both sides of the lower forehead.

[Picture 2] Stone pillars and figures from the Eastern Han Dynasty

1. A-type stone pillar (Langxiexiang Liujun Shinto stone pillar)

2. B-type stone pillar (Qinjun Shinto stone pillar)

3. Type A Stone Man (Stone Man of Zhangqu Village, Qufu)

Respectively taken from "The Complete Collection of Chinese Tomb Sculptures: The Three Kingdoms of the Eastern Han Dynasty" edited by Jie Lin Tongyan, plates 48, 46, 1

Type B, the main body of the column is decorated with longitudinal concave straight lines, also known as "concave straight lines". There are only two stone pillars from the Qinjun Shinto in Beijing [Figure 2:2]. They are of the same shape, with a columnar square forehead, the official script "Han Gu Youzhou Qinjun Shinto", and a chi tiger under the forehead.

Among the A-shaped pillars, Mr. Wang Xiantang confirmed that the owner of Liu Jun's Shinto stone pillar tomb was the brother of Liu Heng, the king of Bohai, who died in the eighth year of Yanxi (165); the Qin Jun Shinto stone pillar with B-shaped pillars was clearly dated to the first year of Yuanxing. (105) Made. However, due to the lack of materials, it is difficult to determine the age of these two types of stone pillars.

3. Stone Man

According to the difference in the overall image of the stone figures, they are divided into two types: A and B.

[Picture 2] Stone pillars and figures from the Eastern Han Dynasty

4. Type A Stone Man (Stone Man of Zhangqu Village, Qufu)

5. 6. Type B Stone Man (5. Qingzhou Waterfall Stream Stone Man 6. Linzi Renmin Road Stone Man)

Respectively taken from "The Complete Collection of Chinese Tomb Sculptures: The Three Kingdoms of the Eastern Han Dynasty" edited by Jie Lin Tongyan, plates 2, 10 and 11

Type A, the image of Han officials and soldiers. There are several examples of paired configurations. It is common for a person to have his hands arched in front of his chest, as if holding a shield with both hands horizontally; a person is holding a handle with both hands on his shoulders. The object may be a comet, or a weapon such as a sword or a ax; It should show the image of the pavilion chief and soldiers. The stone figures seen in Zhangqu Village and Taoluo Village in Qufu, Shandong Province belong to this type [Figure 2: 3, 4]. The chests of the stone figures in Zhangqu Village are engraved with the words "Hongjun Tingzhang, the former prefect of Le'an in the Han Dynasty" and "Pawn of the Mansion Gate" respectively, indicating the symbolic significance of this type of stone figure. This type of stone figure can also be seen holding a sword with both hands, such as a stone figure unearthed from Xinjin, Sichuan, which was originally placed in Zhao Jun's cemetery.

Type B, the image of a barbarian. The standard shape is characterized by sitting in a posture, a pointed hat, deep eyes and a high nose. It is common to see a pair of gloves stacked on the front of the chest. Stone figures of this type have been unearthed from Pushuijian in Qingzhou, Shandong Province (Figure 2: 5), Renmin Road in Linzi (Figure 2: 6), Zuojiazhuang, Xuyao Village and other places.

Among the type A stone figures, Mr. Yang Kuan verified that "Hongjun" was the Duke of Heji who succeeded Le'an as prefect in the first year of Emperor Zhi's reign (146). If there are no accidents, the Zhangqucun stone figures should have been made after Emperor Zhi. During the Huan and Ling periods. Therefore, the A-type stone figures with highly similar shapes should be dated to around the late Eastern Han Dynasty. There is no clear dating material for Type B stone figures. Mr. Zheng Yan speculated that the Qingzhou stone figurine was a work of the second century AD based on the money patterns and water ripples decorated on it; Mr. Lin Tongyan compared the double-stacked posture of this type of stone figurine with the ceramic figurines in the tombs of the Western Jin Dynasty in the Three Kingdoms, and concluded that it was of the same age. It may be later than the Eastern Han Dynasty (the lower limit can be as late as the Western Jin Dynasty). Type B stone figures are mainly found in Shandong. However, due to the impact of the Qingxu Yellow Turban Army and the thin burial policy, the stone carving craftsmanship in this area has declined greatly after the end of the Han Dynasty, and there should be no conditions for making such large stone carvings. Taken together, the middle and late Eastern Han Dynasty may be the time when Type B stone figures were produced.

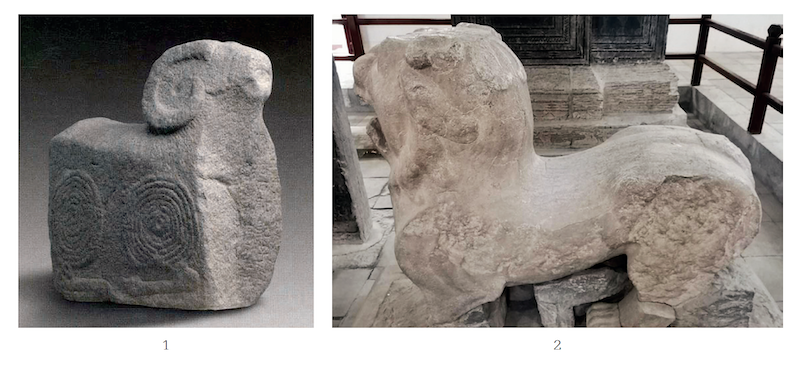

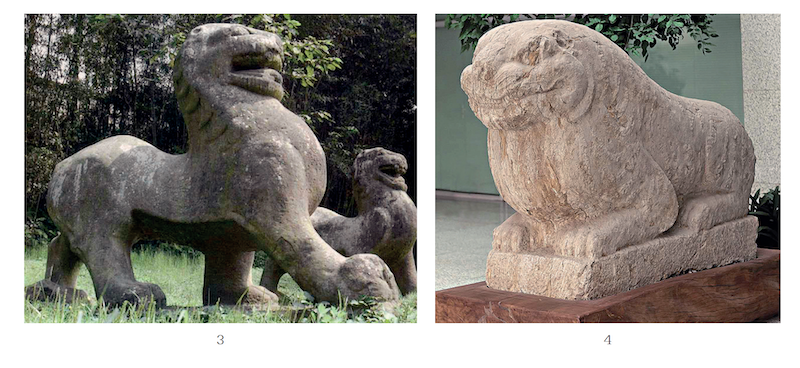

4. Stone beast

The stone beasts here specifically refer to stone carvings based on real-life animals. The stone-winged beasts with obvious deified characteristics need to be discussed separately due to their large number and great influence on future generations. Literature records that the stone animals in the Eastern Han Dynasty tombs include lions, tigers, sheep, horses, oxen, camels, elephants, etc.; except for oxen and camels, all other animals have physical data in existence (Figure 3). In terms of shape, most stone lions are carved on a square base in a standing or marching posture; stone sheep and stone tigers still do not have four legs or the legs are not obvious, and the animal body is integrated with the stone itself. In addition, some stone beasts show a non-realistic style, with their bodies slightly idealized in an "S" shape (Figure 3:3). Except for the fact that there are no wings on both sides, they are very similar to the shape of stone-winged beasts.

[Picture 3] Examples of stone beasts from the Eastern Han Dynasty

1. Sun Zhongqiao's Stone Sheep is taken from "The Complete Collection of Chinese Tomb Sculptures: The Three Kingdoms of the Eastern Han Dynasty" edited by Jie Lin Tongyan, plate 43

2. The stone lion of Wu’s Temple in Jiaxiang was photographed by the author

[Picture 3] Examples of stone beasts from the Eastern Han Dynasty

3. The stone lions on Yang Jun's tomb were taken from "The Complete Collection of Chinese Tomb Sculptures: The Three Kingdoms of the Eastern Han Dynasty" edited by Jie Lin Tongyan, plate 17

4. Stone tiger collected in Xuzhou Museum, photographed by Liu Cong

Among the stone animal materials, the following examples have relatively clear dates: the stone sheep of Sun Zhongqiao in the fifth year of Yonghe in Yishui (140) [Figure 3:1], the stone lion of Wushi Temple in the first year of Jianhe in Jiaxiang (147) (Figure 3:2) , stone beasts on Li Gu's tomb in the first year of Jianhe's reign in the city, stone tigers on Kong Biao's tomb in the fourth year of Jianning in Qufu (171), stone lions on Fan Min's tomb in Lushan in the tenth year of Jian'an (205), etc. It can be seen that mausoleum stone beasts were mainly popular in the middle and late Eastern Han Dynasty.

[Picture 3] Examples of stone beasts from the Eastern Han Dynasty

5. Stone horse hidden in Sichuan Museum Photographed by the author

6. The stone elephants in Mengjin Xiangzhuang were taken from "The Complete Collection of Chinese Tomb Sculptures: The Three Kingdoms of the Eastern Han Dynasty" edited by Jie Lin Tongyan, plate 12

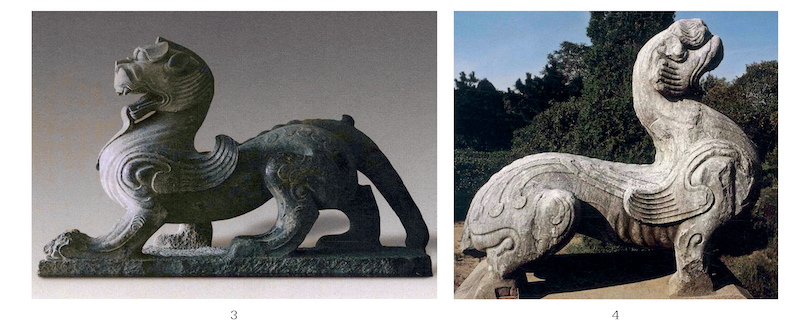

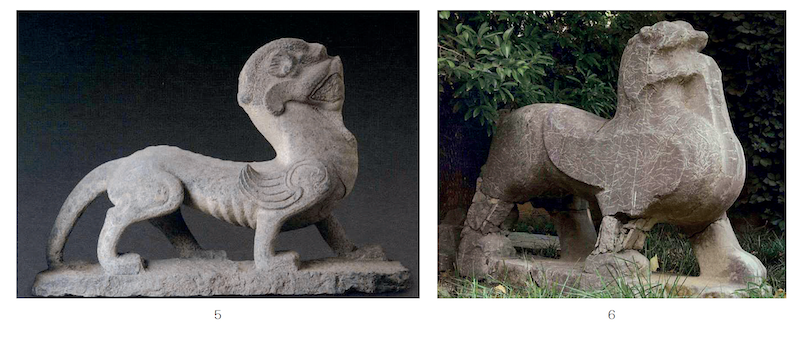

5. Stonewing Beast

From the perspective of cultural communication, Mr. Li Ling believes that China's winged mythical beasts are closely related to the art of West Asia, Central Asia and the Eurasian steppes. The images of winged beasts seen on bronzes and jades from the Pre-Qin to Western Han Dynasties do have the same characteristics. Stronger exotic style. The stone-winged beasts of the Eastern Han Dynasty clearly had a "Sinicization" trend and formed a series of local characteristics. The stone-winged beasts of this period were based on lions and incorporated the characteristics of tigers. Most of them had two wings attached to their arms, and the beast's body presented an unrealistic "S" shape. The so-called "S" shape is mainly generated by the curved shapes of several parts of the animal's body, namely the head and neck, chest, back (including tail), and buttocks. The different degrees of curves in these parts also lead to different specific images of the "S" shape. Based on this, we might as well divide the stone-winged beasts into the following types.

Type A: The animal has a thick body, gentle curves in the head, neck, chest, back and buttocks, and the overall shape is an "S" with small fluctuations. The head is large in proportion, generally without horns, and the two cheeks must be delineated by thick straight lines. The mandibular mandible must hang down and stick to the chest. The wings on both sides are straight back or slightly tilted upward. Examples of this type include the winged beasts from Gao Yi's tomb in Ya'an (Figure 4:1), Fan Min's tomb in Lushan, etc. Although the Yang Jun tomb stone beast mentioned above has no wings on both sides, its modeling characteristics are similar to this type.

[Figure 4] Main types of stone-winged beasts of the Eastern Han Dynasty

1. Type A (winged beast from Gao Yi's tomb) 2. Type B (winged beast from Sun Banner, Luoyang)

Respectively taken from "The Complete Collection of Chinese Tomb Sculptures: The Three Kingdoms of the Eastern Han Dynasty" edited by Jie Lin Tongyan, plates 40 and 25

Type B: The beast has a slender body, a slanted neck, a smooth chest, and a long tail with a larger curvature on the buttocks. The overall shape is an "S" shape with a straight and incomplete upper end. The head is small in proportion, with one or two corners extending upward on the top of the head, and the ears are in the shape of smaller petals. The lower jaw has a beard and is shaped straight down to the chest. The wings are long strips diagonally upward, with feather-like decorations. The stone-winged beasts seen in Sunqitun, Luoyang, Henan (Figure 4:2), Pengpo, Yichuan, etc., as well as in the Yanshi Mall Museum, belong to this type. The stone beasts seen in Yulin, Xuchang and Shenjia Village, Xianyang have no wings on both sides, but the overall shape is similar to this type. The two stone-winged beasts collected by the Xuzhou Museum in 2010 are both unfinished semi-finished products, but judging from their basic shape, they should also belong to this type.

Type C: The body of the animal is short and short, the head and neck curve is gentle, the chest, back and buttocks have obvious curves, and the overall shape is short "S". The head is large in proportion, with one or two corners attached to the top of the head. The ears are in the shape of larger petals, and the eyebrows are thick and raised. The two cheekbones are described by thin lines and curves. The lower jaw has whiskers, which mostly droop to the chest in a streamlined shape. The two wings are half-moons with upturned tips, and the surface is decorated with curved patterns. The body of the beast is gorgeously decorated, with horizontal or diagonal convex string patterns on the chest, and beaded ridges and cirrus patterns on the back. The winged beasts seen in Youfang Village in Mengjin, Henan (Figure 4:3), Baijiamen and Shuangli Village in Yuzhou, Shifang Village and Wu Village in Neiqiu, Hebei, and Yaozhuang, Linquan, Anhui, all fall into this category.

[Figure 4] Main types of stone-winged beasts of the Eastern Han Dynasty

3. Type C (Winged Beast from Youfang Village, Luoyang) 4. Type D (Winged Beast from Zongzi Tomb)

Taken respectively from "The Complete Collection of Chinese Tomb Sculptures: The Three Kingdoms of the Eastern Han Dynasty" edited by Jie Lin Tongyan, plates 24 and 35

Type D: The shape and detailed decoration are very similar to Type C, except that the neck curve is more obvious, resulting in a more slender "S" shape overall. The stone beasts found in Nanyang Zongzi's Tomb (Figure 4:4), Xuchang Xiangcheng and other places belong to this type.

In addition to the above types, there are some special materials that need to be accounted for separately. The winged beast from Nanguan, Huaiyang, Henan Province is generally of type B, but the details of the head have the characteristics of type C. It may be a transitional form from type B to type C [Figure 4: 5]. The stone winged beasts found in the ancient town of Pizhou, Xuzhou City, Jiangsu Province are thick and solemn in shape, with their mouths and tongues hanging out. They are obviously different from the mainstream shapes of the above-mentioned winged beasts (Figure 4: 6).

[Figure 4] Main types of stone-winged beasts of the Eastern Han Dynasty

5. Between type B and type C (winged beast from Nanguan, Huaiyang) 6. Alien type (winged beast from ancient town of Pizhou)

Respectively taken from "The Complete Collection of Chinese Tomb Sculptures: The Three Kingdoms of the Eastern Han Dynasty" edited by Jie Lin Tongyan, plates 31 and 37

In terms of dating, Type A Fan Min's tomb and Gao Yi's tomb date from the 10th year of Jian'an (205) and the 14th year of Jian'an (209), so the popularity of this type of winged beast is roughly at the end of the Eastern Han Dynasty. As for the three types B, C, and D, they all basically come from the Central Plains area. The "S" shape seems to have a gradually improving pattern. Especially considering the existence of the transitional form of the Nanguan winged beast in Huaiyang, Henan, the author is inclined to There is an evolution sequence of B→C→D. In Type B, some scholars have concluded that it was made in the mid-to-late Eastern Han Dynasty through the calligraphy style of the inscription "Fengshi Artemisia Jucheng Nu Zu" inscribed on the Tunyi Beast of Sun Banner, and by comparing the related artifacts in the tomb excavation materials. Among type D, although there is no chronological data in Zongzi's tomb, according to the life of the tomb owner, the time when the winged beast was made is at or around the end of Emperor Huan. It can be preliminarily judged that this type was popular in the late Eastern Han Dynasty. The relative age of type C can be roughly placed between types B and D. Of course, there is not necessarily a substitution relationship between B, C, and D. After the new shape is produced, the old shape may still be used.

6. Stone tablet

There are more than 40 actual gravestones (including those with only rubbings remaining) in the cemetery. There are also some severely damaged fragments that may also be tombstones, so the actual number should be more than these. Tombstones of the Eastern Han Dynasty include two parts: the body (mostly pierced) and the base. The shape of the stele body can be divided into three categories: Type A, Guishou stele, Dunhuang Changshiwu Monument, Yanmen Prefecture Xianyuhuang stele, etc. all belong to this category. Type B, round-headed monument. Some of the stele heads have no decoration, such as the Taishan Duwei Kong Zhou stele, the Quren Ling Jingjun stele, etc.; some have faint heads, such as the Kong Qian stele, the Yuzhou engaged Kong Bao stele, etc.; some have Chi heads, such as the Wang Sheren stele. , the monument of Fan Min, the governor of Bajun, etc. Type C, flat-headed monument. There are very few in number, such as the Wang Xiaoyuan Monument. The stele base can be divided into two types: an overturned bucket-shaped square base and a turtle base. The latter is often combined with the round-headed stele body. However, the number of tombstones with both the base and the body of the tombstone is relatively small, and the combination of the two is difficult to discuss in detail. Tombstones are mainly inscribed with text, and the contents mainly include the tomb owner's life, achievements, and burial process. Gradually, a fixed format has been formed, and even formal "grave flattery" remarks have been produced. There is also a type of stone steles, which are very few in number, such as the Wang Xiaoyuan Stele and the Qu Renling Jingjun Stele. The body or head of the stele has relief images, which is contrary to the mainstream of tombstones in the Han Dynasty, but is closer to the portrait stones that decorate underground tombs.

Since most of them have clear dates, the age of the stone tablets can be relatively clearly defined. The early and middle Eastern Han Dynasty before Emperor Huan was the initial stage of development of tombstones. At this stage, the stele body has three types of shapes, with type A being the main type, and types B and C being less common; the base of the stele is rarely preserved; and the writing format of the stele is not yet fixed. The period of Emperor Huan and Emperor Ling was the period when the largest number of surviving tombstones existed, and it was also the period when the shape of tombstones was finalized. Generally speaking, the stele body is mainly B-type, with less A-type and almost no C-type. The tortoise-shaped stele base also appeared during this period, such as the Wangsheren stele in the sixth year of Guanghe period (183). The writing of inscriptions began to form a fixed pattern since the first year of Wu Banbei's construction. In the late Eastern Han Dynasty after Shaodi, the number of tombstones generally decreased, but there was significant development in some areas, and the shape and inscriptions basically continued the characteristics of the previous stage.

The above is an overview of the main shapes and popular ages of stone carvings in Eastern Han Dynasty cemeteries. [Table 1] is used to briefly summarize these contents.

[Table I]

Continue [Table 1]

2. Space configuration

Spatial configuration refers to the layout and arrangement of different forms of stone carvings within the tomb area. Compared with the study of form, it is more difficult to study the spatial configuration of tomb stone carvings. The main reason is that most of the combinations of ground stone carvings that can be observed today are incomplete and their locations have often been displaced. Fortunately, some handed down documents, including "Shui Jing Zhu", record the layout of some Eastern Han cemeteries, which can be used as a reference for restoration. Following this line of thinking, Mr. Wu Hong has long discussed the basic characteristics of the Eastern Han Dynasty cemetery design as follows: "The boundaries of the cemetery tomb area are marked by a pair of stone gates, and the Shinto extending inward between the gates forms the axis of the cemetery. When approaching, There are pairs of stone beasts or stone figures on both sides of the Shinto of Quemen. At the end of the Shinto are the tombs...sometimes before sealing the earth, ancestral halls and tombstones are built." It can be said that the above discussion is a classic of the spatial arrangement of stone carvings in Eastern Han mausoleums. Generalization. Based on Mr. Wu Hong's discussion, this article will start with the significance of different stone carvings in funeral activities and restore some details of the spatial configuration.

First, let’s discuss the stone carvings that have the function of “marking the tomb area”, mainly including stone towers, stone pillars and stone tablets. It is uncontroversial that the stone tower is located at the entrance of the tomb, but the location of the stone pillar needs to be reconsidered. According to the phenomenon that the Shinto pillars and stone towers of Qinjun in Youzhou appeared together, some scholars believe that the Shinto stone pillars were erected in front of the stone towers, which was intended to integrate the tomb towers and stone pillars. However, according to literature records, stone pillars are generally placed on both sides of the temple gate. For example, Qiaoxuan Cemetery has two stone pillars placed on the south side of the stone temple. Therefore, it can be said that stone towers and stone pillars mark the starting point and end point of Shinto respectively, and the main body of Shinto is between the two. The que outside the garden marks the tomb area, reminding those who come to pay homage to "think about the que" and review their etiquette; the pillars outside the temple mark the residence of the "soul" of the tomb owner, representing the end of the open space of the cemetery. In addition, there may have been Shinto pillars made of other materials instead of stone pillars at that time. For example, in the cemetery of a certain king in Xipingzhong, "the bricks were exhausted to make Baida bricks." At the end of the Shinto, one or several tombstones are placed between two stone pillars at the end of the Shinto. Generally, tombstones are erected by the tomb owner’s disciples, former officials, and relatives who come to express their condolences. In this case, placing the tombstone recording the merits and deeds at the end of the area where strangers can reach seems to be the best manifestation of their efforts to express their condolences. We can even guess that the original intention of writing the name of the person who erected the monument on the underside of the stele may be to inform the owner of the tomb of the list of future deceased.

Then let’s look at the stone men, stone beasts, and stone-winged beasts whose main function is to protect the tomb. Within the stone palace, stone figures and prone stone tigers and stone sheep are often placed on both sides of the shrine. There are two types of stone men: A and B. Type A stone figures represent the heads of pavilions and soldiers. Mr. Xin Lixiang's research found that the images with the inscription "Duting" seen on the portrait stones and murals of the Han Dynasty represent ancestral temples. The so-called "Duting" means "the pavilion that governs the capital". The "Pavilion" in the Han Dynasty had a pavilion chief and pavilion soldiers, who were responsible for guarding, arresting, and welcoming visitors. According to this, the A-shaped stone figures placed in the cemetery should have the meaning of guarding and greeting the mourners outside the ancestral hall. They should also be located near the ancestral hall and the stone pillar combination. "Shui Jing Zhu" records that in Zhang Boya's cemetery, "there is a stone temple in front of the tomb, with three steles planted...and two stone figures beside the monument." This is an example of this location relationship. The funerary significance of type B stone figures may be slightly different. Type B stone is a human image of a barbarian. Based on the analysis of Hu figurines found in tombs, Mr. Wu Zhuo found that the funeral activities during the Eastern Han Dynasty included "popular Buddhist religious rituals" in which Hu people participated. Mr. Huo Wei believes that one needs to be cautious about the existence of religious rituals, but it is generally true that Hu people generally participated in funeral activities in China. Placing B-type stone figures in the cemetery may be a simulation of similar funeral activities. The installation of stone tigers is usually considered to be related to driving away elephants. As stated in "Customs": "Elephants like to eat the liver and brains of the dead... The elephants are afraid of tigers and cypresses, so tigers and cypresses are erected in the cemetery." The meaning may be similar. Some scholars have verified that sheep were sometimes regarded as evil beasts in the Han Dynasty, so placing stone sheep could also protect the tomb owner. In addition, there are also stone (winged) beasts distributed at the entrance of the tomb area, forming a spatial combination relationship with the stone palace. According to the combination of objects seen in Jiaxiang Wu's Tomb, Gao Yi's Tomb and other places, those who match the stone tower, whether it is a realistic lion or an idealized winged beast, should be in a standing posture. This may be because the funerary significance of the stone beasts placed here is not only to suppress the tomb and exorcise evil spirits, but also to serve as a "precursor" ceremonial guard. The standing shape is obviously more in line with this functional requirement. In contrast, the stone sheep and stone tigers, which are closer to the tomb owner in space, are often shaped into prone postures ready to go.

To sum up, on the basis of fully considering the functional significance of the stone carvings, we can summarize the spatial configuration of the stone carvings in the mausoleum as follows: the stone palace and the standing stone lions and winged beasts stand outside the cemetery, marking the starting point of the Shinto; the stone figures and the prone figures Stone tigers and stone sheep are placed on both sides of the Shinto in the garden; stone pillars are erected outside the ancestral hall to mark the end of the Shinto; and stone tablets are placed between the two stone pillars. Of course, this is just a more idealized model. In actual construction, Eastern Han dynasty cemeteries often simplified some of the above elements to form a more compact layout.

3. Regional Characteristics Analysis

Since stones are also used in funeral activities, the regional distribution of portrait stones has certain reference significance for our study of stone carvings on mausoleums. Referring to Mr. Yu Weichao's summary of the five distribution regions of portrait stones in the Han Dynasty, combined with the physical distribution of stone carvings in graveyards and documentary records, we can list the following five regions with their own characteristics.

Area I: Today's northern Lu, southwestern Lu, and southeastern Lu; approximately equivalent to Shanyang County, Rencheng Kingdom, and Taishan County in Yanzhou during the Eastern Han Dynasty, Lu Kingdom and Langye Kingdom in Xuzhou, and Jinan Kingdom and Qi Kingdom in Qingzhou. This area is widely distributed and has a high level of development of cemetery stone carving technology, which is mainly reflected in the following aspects. First, in terms of age, the stone carvings in this area are the earliest. The He Xiaoyu stele can prove that the prototype of tombstones has appeared in the late Western Han Dynasty. Junan Sunshi Que, Pingyi Gongcao Que, Pingyi Huangshengqing Que and other examples have been dated. The earliest stone tomb of the Eastern Han Dynasty is also located in this area. Secondly, in terms of the categories of stone carvings, the existing objects in this area include all the types and most shapes of the cemetery stone carvings mentioned above. Thirdly, in terms of modeling and craftsmanship, this area has developed a style that pursues realism. For example, it is common to use A- and B-type stone figures to reproduce the scenes of funeral activities. Even lions that are difficult for ordinary people to see are also found in Jiaxiang Wu Cemetery in this area. Reproduce to the greatest extent possible. In addition, under the traffic conditions at that time, "Lu Gongshi Juyi" went to Youzhou to manufacture the Qinjun Shinto Pillar, which also shows from the side that this area is famous for its stone carving craftsmanship.

Area II: the area from southern Henan to northern Hubei, approximately equivalent to Nanyang County in the Eastern Han Dynasty. There are few existing physical objects in this area, represented by the D-type stone-winged beast from Zongzi Tomb in Nanyang, as well as the fragments of stone beasts from Dongguan and Wangcun in Nanyang, and the stone sheep from Tanghe. Checking "Shui Jing Zhu", we can see two examples of stone carvings in cemeteries in this area: (Xiangyang) Cai Mao's tomb "the stone is carved in the shape of a big deer", (Gucheng) "General Wen's" tomb "has stone tigers and stone pillars in front of the tunnel". Although the number of stone carvings currently available is small, considering the level of craftsmanship of the portrait stones in this area and the maturity of the "S" shape of the winged beast in Zongzi's tomb, we have reason to believe that the level of stone carvings in this area should not be low. During the Northern and Southern Dynasties, the forces of the South and the North often competed repeatedly for this area. This may be the reason why there were not many stone carvings on the ground in the Northern Wei Dynasty where Li Daoyuan lived.

Area III: the area from Guanzhong to Hanzhong, approximately equivalent to Jingzhaoyin and Hanzhong counties in the Eastern Han Dynasty. The relatively clear ones in this area are the stone beasts from Li Gu's tomb in Hanzhong and the stone beasts from Shenjiacun in Xianyang. The former was seriously damaged. The ages of the stone beasts from Shichuan River in Lintong and the stone beasts from Zhang Qian's tomb are still controversial. There is still little overall data, and it is difficult to discuss regional characteristics in detail. However, judging from the stone beasts seen so far in Shenjiacun and Zhangqian's tombs, they are obviously influenced by the shapes of stone carvings in Luoyang. The Guanzhong stone carving craftsmanship, which once produced the Huo Tomb Stone Carving Group in the Western Han Dynasty, has declined in development as its political status in the region has declined.

Area IV: Sichuan and Chongqing area, approximately equivalent to Shu County, Guanghan County, and Ba County in northern Yizhou during the Eastern Han Dynasty. This area has outstanding regional characteristics, including B-type stone towers, A-type winged beasts and other stone carvings, which are basically only found in this area. At the same time, it is not uncommon for the area's stone carving crafts to interact with other areas. First of all, the shape of the stone-winged beast may have been influenced by the stone carving craftsmanship in the north. The A-type winged beasts in Sichuan are mainly of type A. The tombs of Fan Min and Gao Yi are clearly dated, which are later than the C and D-type winged beasts in the Central Plains. The shape may refer to the "S" shape of these two types of stone beasts, and express it in a gentler shape to better meet the aesthetic needs of local patrons. In the late Eastern Han Dynasty, the turmoil in the Central Plains promoted population mobility, and Yizhou, where the situation was relatively relaxed, became one of the options. "Book of the Later Han·Liu Yan Zhuan" records that "tens of thousands of households from Nanyang and Sanfu migrated to Yizhou, and Yan all accepted them as a crowd." These immigrants may have stone carving craftsmen, or at least brought with them the funeral culture of their original areas. . Secondly, the B-type stone palace had an impact on the stone carving craftsmanship in other areas. This type of stone monument has complex craftsmanship and the actual objects seen are mainly distributed in this area. It is a representative of local stone carving products. "Shui Jing Zhu" records that the stone tower (building) of Prince Ya of Xi'e in Nanyang said: "It is supported by luancotons and four annotations on the carved eaves. The carvings are exquisite and wonderfully artificial." Wang Ziya was once the captain of the vassal state of Shu County. , this kind of complexly carved stone towers is rare in Nanyang, and it should be related to the stone towers in Shu under its rule.

Area V: Central Henan, approximately equivalent to Henan Yin during the Eastern Han Dynasty. The types of stone carvings seen in this area are relatively single, but the number of stone-winged beasts is relatively large, and an evolutionary sequence of B→C→D has been formed in the area. Therefore, this area is likely to be the independent invention area of stone-winged beasts, or at least the area leading the styling trend. It is generally believed that this type of stone-winged beast has a certain connection with extraterrestrial civilizations. According to historical records, Emperor Ling liked Hu Feng, and "all the nobles and relatives in Kyoto competed for it." The popularity of stone-winged beasts around the capital may be related to this. The mainstream form of stone-winged beasts dominated by this area had a great influence on the stone carving technology in other areas of the Eastern Han Dynasty. It ranged from Xuzhou in Jiangsu to the east, Neiqiu in Hebei to the north, and Nanyang to the south. It even gave rise to the four regions mentioned above. imitate and transform it. Many cemeteries in the "Shui Jing Zhu" recording area have stone carvings, such as the cemetery of Zhao Yue, the prefect of Guiyang, and the cemetery of Zhang Boya, the prefect of Hongnong. Therefore, the popularity of stone carvings in this area may be higher than the physical remains indicate.

The above is the main overview of the regional distribution of stone carvings in Eastern Han Dynasty cemeteries. The craftsmanship characteristics of the stone carvings in each district are, on the one hand, related to the regional culture, and on the other hand, they are likely to be dominated by a group of craftsmen with relatively fixed activities in the area. These craftsman groups often have orderly inheritance within them, ensuring the stability of the stone carving cultural tradition within these core areas. This may have provided technical support for these regional styles to transcend time and influence the later stone carving system.

Four levels of analysis

When discussing the grade of stone carvings in Eastern Han dynasty cemeteries, academic circles often quote the "Sheep and Tiger Tiao" in "Feng Shi Wen Ji Ji": "Since the Qin and Han Dynasties, the stone unicorn, stone ward off evil spirits, and stone horses in front of the imperial mausoleums are of the same type. In the cemeteries of Renchen, there are stone sheep, stone Tigers, stone figures, stone pillars, etc., all decorate the tomb ridges like the elephants and guards in life." However, this is only a general impression of Feng Yan, and the grade of the stone carvings in the Eastern Han Dynasty tombs needs to be analyzed in detail.

First, we need to discuss whether the regulations on imperial tombs include above-ground stone carvings. According to the records of "four exits of Sima Gate" from the Han emperor's mausoleum in the Middle East, some scholars believe that there should be a gate outside the gate. However, except for the tomb of Emperor Guangwu of the Eastern Han Dynasty, all the imperial mausoleums used "walking horses" instead of walls. The stone gates set up outside the doors obviously did not match the architectural style. In terms of stone animals, two documents in "Shui Jing Zhu" are often cited: "(The stone horse of Caosong Tomb) is not as good as the horse represented by Guangwu Tunnel" and "(Zhongshan Jian Wang Yan) plucked stones from Zhuojun Mountains and used trees to build tombs." "The mausoleum, tunnel, and stele beasts came out of this mountain, and two stone tigers were left behind. Later generations named the hill after it." This seems to indicate that the imperial tombs also had stone carvings on the ground. However, the imperial mausoleums of the Eastern Han Dynasty after the original mausoleum were even more simplified, and the funeral ceremony of Liu Yan was extremely extravagant, so that "the system is beyond the reach of other countries." Therefore, even if the above records are true, they should be regarded as a few special cases and not the norm in the Han system. In terms of physical data, the C-shaped winged beast seen in Mengjin Youfang Village was considered to be related to the imperial mausoleum. This is an inference based on the "Liu Xiu Tomb" in Tiexie Village as the original mausoleum. However, now that the possibility that the "Liu Xiu Tomb" is related to the original tomb has been basically ruled out, the above inference is difficult to establish. In addition, Mr. Yang Kuan believes that the stone elephants in Luoyang Xiangzhuang are related to the imperial mausoleum, but it is difficult to make a conclusion at present. Therefore, we can generally believe that, with a few exceptions, the mausoleum system of the tombs of emperors and kings of the Eastern Han Dynasty did not include stone carvings on the ground.

Examining the clear information of the tomb owners, we found that the class of emperors and kings who accepted the stone carvings on the ground was very wide, ranging from the three princes to the common people. According to the identity of the tomb owner, it can be roughly divided into the following levels:

1. The stone carvings in the tombs of princes and three princes include ques, pillars, stele, winged animals, sheep, tigers, horses and other stone animals. The number of cemeteries of this level is relatively small. The ones with physical data are the tombs of Da Sinong and Taiwei Li Gu. However, the stone animals in the tombs are so damaged that they cannot be identified. There are also a few tombstones whose owners are San Gong. According to the literature records, four more examples can be added: the Tomb of Jichenghou Zhoufu, the Tomb of Hanyang Tinghou Cai Mao, the Tomb of Taiwei Cao Song, and the Tomb of Taiwei Qiaoxuan.

2. For officials from prefectures and counties with a weight of one thousand to two thousand stones, the stone carvings in their cemeteries mainly include ques, pillars, steles, stone animals, etc. For example, the cemetery of Zhao Yue, the prefect of Guiyang, is equipped with stone tablets, stone pillars, stone oxen, stone sheep, and stone tigers; the layout of the cemetery of Zhang Boya, the prefect of Hongnong, is more complex, and the types of stone carvings mainly include stone tablets, stone columns, stone pillars, stone figures, and various animals. .

3. Governors, county magistrates, county magistrates, and county officials with an income of six hundred stones or less. Most of the physical objects stored in the cemetery are ques, but according to documentary records, there are also stone carvings with a richer variety. For example, Chang Yinjian's cemetery in Anyi has monuments, monuments, stone lions, stone pillars, stone sheep, etc.

In addition, some tombstones of three elders, non-official civilians, and women still exist, but the combination of stone carvings is unknown, so they are not listed here.

There seems to be no obvious difference in the types and combinations of stone carvings among the above-mentioned levels of cemeteries. Due to the lack of clear physical materials about the tomb owner, it is difficult to conduct comparative research on the shape and size of similar stone carvings in different strata. Among them, the shape of the que seems to be classified into two-out que and single-out que. However, how to define a large number of uninscribed ques requires further study. Therefore, at present, it is difficult for us to see that there is a complete system of hierarchical distinctions in stone carvings.

In summary, during the Eastern Han Dynasty, above-ground stone carvings were basically not found in imperial tombs, but they were accepted in cemeteries of multiple classes below the royal tombs. At the same time, there was no obvious difference in the types and combinations of stone carvings in cemeteries of different classes.

5. Conclusion: The manifestation and essence of the prevalence of stone carvings in Eastern Han dynasty cemeteries

This article analyzes four aspects of the stone carvings in Eastern Han dynasty cemeteries: First, the rich variety of stone carvings have formed several relatively fixed shapes within them, and some have even formed a complete development sequence. Second, the spatial configuration of stone carvings has a stable pattern based on functional meaning. Third, there are five main distribution areas. The stone carving shapes and techniques between each area have their own characteristics, and there are common exchanges and references. Fourth, it has a wide range of usage classes and has been accepted by cemeteries of many classes below royal tombs.

The above four points can correspond to the four aspects of the high development of above-ground stone carvings, and they were all in place by the middle and late Eastern Han Dynasty at the latest. Further, we conducted an in-depth analysis of the third and fourth points mentioned above, and the essential attributes of this prosperous situation have also begun to emerge. The high development of regional characteristics of stone carving crafts in each district seems to indicate that there is no universal paradigm for tomb stone carving across the country; and the use of classes can better explain the absence of central power and the dominance of local forces. Therefore, the prevalence of stone carvings in graveyards may not be a top-down "regulation", but more a "fad" established by convention. If combined with the political situation of the Eastern Han Dynasty, we can have a deeper understanding of this point.

Before the middle of the Eastern Han Dynasty, the political situation was still stable. The funerals of Emperor Guangwu Liu Xiu and Zhongshan Jian King Liu Yan may contain content on the stone inscriptions on the ground. There are fewer similar actions by other classes, but there are some simple activities of building monuments and monuments. It is also common in literary records that officials take the lead in erecting monuments. The components of the Qinjun Stone Tower in Youzhou also record the emotion of "the bandit loves money and is forced by the system." It can be seen that in addition to the occasional attempts by members of the royal family, the related behaviors of other classes in cemetery stone carvings are also subject to official regulations. After the middle of the Eastern Han Dynasty, due to the influence of the exclusive power of relatives and eunuchs, the imperial power declined, and those who "reached the throne of the Three Dukes" were often in danger. On the contrary, affected by political corruption and the need to suppress civil unrest, the power of local officials and wealthy families gradually increased, and by the end of the Han Dynasty, it became an important factor in splitting the imperial power. Politically powerful local officials and wealthy families also tended to go beyond etiquette in funeral activities to show off their power. In the past, academic circles have recognized that the large-scale tombs with three front, middle and back chambers appeared in large numbers after the middle of the Eastern Han Dynasty, which was a manifestation of the above-mentioned attempts in the underground burial system. In terms of ground structure, ground stone carvings were rare in the past, and they can create a "public" cemetery atmosphere, so they are naturally an excellent choice to express similar appeals. In addition, a large number of Confucian scholars had to rely on the chief executive because the regular promotion channels were blocked, and a strong network similar to the "relationship between emperor and minister" was formed between the two. These disciples and former officials also had responsibilities and obligations for the posthumous affairs of the local officials they were attached to, including mourning and setting up tombstones. This obviously encouraged the trend of stone carvings in cemeteries.

In short, the stone carvings on the mausoleums that were “in a good situation” after the mid-Eastern Han Dynasty confirmed that regulations and restrictions had become “just a formality.” Therefore, the prevalence of stone carvings on mausoleums should be, in essence, a special custom of local forces showing off their power. Of course, we should also note that it is these soft funeral customs that have been sublimated into "stories" that can be traced and imitated in later generations. They have had a certain impact on the mausoleum stone carving system since the Southern and Northern Dynasties, making the above-ground stone carvings complete. The transformation from "fad" to "system". The matter is so large that it will be discussed in another article.

Note: Thanks to Mr. Liu Cong of the Xuzhou Folk Museum for providing clear photos of several stone beasts in the Xuzhou area, the author was able to observe their complete shapes. I would like to express my sincere gratitude.

(The author of this article is from the School of History and Culture of Shandong University. The original title is "Archaeological Research on Stone Carvings in Eastern Han Cemetery". The full text was originally published in the "Journal of the Palace Museum" Issue 11, 2023.)