"No brave man is born brave; courage is developed through training and discipline." - Vegetius Renatus, "On Military Affairs"

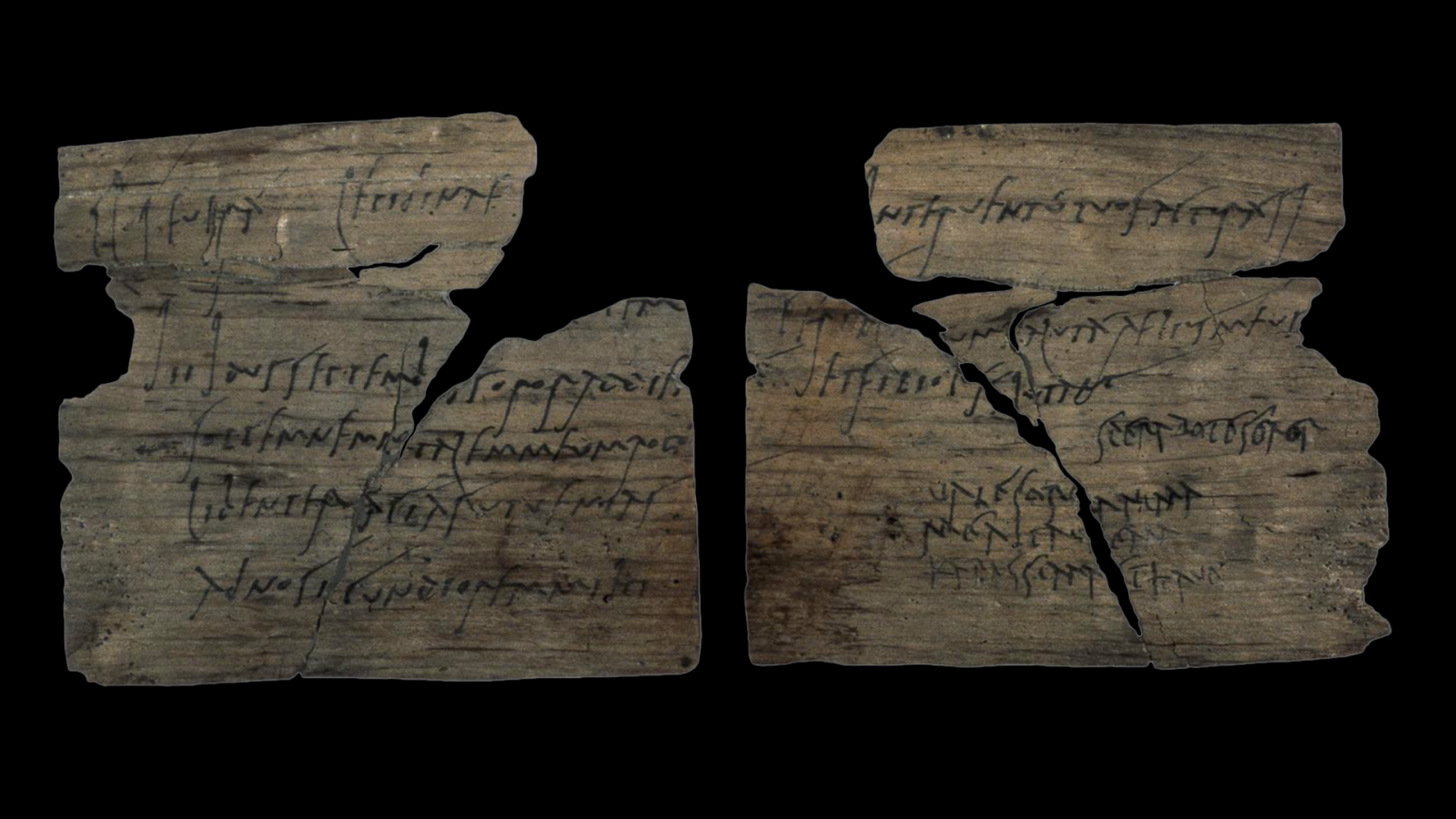

The Paper has learned that on February 1, the British Museum’s new exhibition “Legion: life in the Roman army” opened. The exhibition travels across the ancient Roman Empire and includes papyrus letters written by Roman Egyptian soldiers and the Vindolanda tablets - one of the oldest surviving handwritten documents in Britain. Through the military career of an ordinary Roman soldier (from enlistment to campaign, to fortress life and garrison, and finally to retirement), it reveals the daily life of soldiers and the women, children and slaves who accompanied them.

Bronze cavalry helmet, England, 1st century AD.

The territory of the Roman Empire exceeded 4.5 million square kilometers, which came from the invincible military dominance of the Roman legions. The Roman legion was also the "engine" of Roman civil society. Rome's military history may date back to the sixth century BC, but it was not until the first emperor Augustus (63 BC – 14 AD) that soldiering became a career option. While the rewards of military life were enticing—joining a legion led to generous pensions, barbarian soldiers (those without citizenship) could obtain citizenship for themselves and their families—the dangers were real. Civilians were fearful and hostile to soldiers, and their lives on the battlefield were unpredictable.

The bulk of the Roman army was made up of civilians, but most stories about the Roman Empire only describe the history of power, but the exhibition "Roman Legions" takes a different path. Exhibition: From the perspective of a soldier, what was life like in the Roman army? How do their families feel about life at the fort? "Roman Legions" explores life in settled military communities from Scotland to the Red Sea, through the people who lived there.

Among the exhibits is a strange object - a seemingly large piece of personal armor designed for giants. This makes people feel that those legions who ruled large areas of Europe, North Africa and the Middle East two thousand years ago must have been truly invincible.

Exhibition view of a nearly complete piece of Roman segmented armor, Karl Creese, Germany, 9 AD

However, this armor is not a relic of a Roman victory, but of one of the most disastrous defeats suffered by the Roman legions. It was discovered on a battlefield near the village of Kalkriche in present-day Lower Saxony (northwestern Germany). Here in 9 AD, German soldiers massacred a legion led by Publius Quinctilius Varus (a statesman and general in the Roman Empire under Augustus). The legionnaire wearing this armor may have been slaughtered after the battle, or he may have been paraded as a trophy.

Cultural relics make history visible. As if to be remembered by future generations, the Romans were also extremely skilled at writing history, building an empire, and even produced some of the greatest historians to tell their stories.

So part of the pleasure of walking into the vast exhibition spaces of the British Museum is the instant resonance. Whether your impression of the ancient Roman army comes from Renaissance painter Andrea Mantegna's masterpiece "The Triumph of Caesar" or the movie "Gladiator," you will find the Rome in your heart here.

Here you’ll find the only intact Roman legionnaire shield in the world, its high curved surface painted as finely as a Pompeii fresco and in the deep red favored on the walls of Roman villas. But, there, it symbolizes luxury, while here, it is the color of war. As you can imagine, such a shield would have to be repaired after every battle, washed away with real blood, and given a new coat of paint.

Exhibition site, Roman legionary shields on display.

Weapons from Hadrian's Wall, a stone and earth fortification that cut across the island of Great Britain and was built by the Roman emperor Hadrian, illustrate how soldiers on the Roman frontier waged war. A component called a "tormenta" (a cross between a trebuchet and a super-large crossbow) reveals how metal arrows can quickly fire at any nasty "barbarian". Also from Hadrian's Wall, a dummy used for target practice looks far more brutal and modern than the classical reliefs.

exhibition site

However, the exhibition is not only a bloody carnival of Roman military power, but also an encounter with the warmth of individuals obscured by history. It deftly taps into what was unique about ancient Rome. The surviving remains of other ancient civilizations lean more toward grand narratives: Whether it’s the towering splendor of the Acropolis of Athens or the formidable palace reliefs of Assyrian conquerors, these ancient wonders won’t leave you imagining how ancient people relaxed, joked, or lived. . And the vast material wealth of the Roman Empire left behind amazing relics of the daily life of Roman soldiers - loving letters home.

A pair of children's shoes from Vindolanda, England, 85-410 AD

Roman baths were an essential luxury for those who followed armies to damp places like England. In the exhibition, visitors can see the clogs worn in the bathroom (in both men's and women's sizes) and the games they played in their spare time. One of the most stunning exhibits is a bronze "dice tower."

The women in the military bathhouses were not just slaves, but many were wives of soldiers. They played an important social role in the military camps, as can be seen from the large number of written letters unearthed at Vindolanda on Hadrian's Wall. see. One of the funniest was when Claudia Cervera invited her sister to a birthday party.

A wooden letter unearthed in Vindolanda contains a birthday invitation written in ink by Claudia Severa to her sister Sulpicia Lepidina.

The reality is unbearable when you see the skeleton of a Roman soldier who died in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. He appeared to be assisting in the evacuation of the port of Herculaneum when a wave of hot mud killed him along with many civilians huddled nearby. His sword and dagger are well preserved and still in their scabbards. He didn't die in battle, but to help others - he was a Roman warrior.

Attachment: Roman Legion: Military Career (Text/Carolina Rangel de Lima, Exhibition Project Curator)

The exhibition focuses on the experiences of ordinary soldiers, including citizen legionaries and barbarian soldiers (the non-citizen infantry and cavalry of the regular forces of the Roman Empire), as well as their families.

The exhibition takes the life of Claudius Terentianus, a veteran, as a clue. In several of his letters to his family that have been handed down to this day, Terentianus told the story of his life in about 110 AD. Attempting to join the Legion in 2001, he wrote home asking for clothes and equipment and reported how he tried to integrate. Sent to the east to fight in Trajan's war with Parthia, he eventually achieved his goal and became "a soldier of the legions" and was lucky enough to survive until retirement.

Enlisted in the army

Regular wages and social status proved attractive to potential recruits for the Roman army. Citizens who become soldiers are paid during their service and receive a pension equivalent to ten years' salary upon retirement, but most residents of the empire do not have similar privileges. Leaving aside the desperate plight of the enslaved, most free people also lacked the social status and legal rights of Roman citizens. For non-citizens, joining the Roman army and completing 25 years of military service can obtain Roman citizen status, which will bring an improvement in social status to their families.

Recruitment has strict physical and social requirements: they must be men over 172 centimeters tall, and although there is no minimum age limit, they must join before the age of 35. All recruits are required to have letters of recommendation and undergo grueling training. Free men from across the empire were conscripted into the army, forming a diverse army. Soldiers were often sent to unknown places far from home, serving alongside people from unfamiliar cultures.

Gold stater coin, Roman Republic, 225–212 BC

Once a recruit takes the oath, they cannot back down, and most commit to serving in the military for at least 25 years. Even citizen soldiers lost the right to legally challenge military discipline involving corporal punishment and capital punishment. A gold coin shows the oath taking of the new recruits - two soldiers standing face to face, swords resting on a sacrificial pig held by an attendant. Thereafter, military service can only be terminated by medical treatment, retirement, or death in service.

Ranks and roles

Once inducted, ambitious soldiers seek different roles within the ranks. Among the auxiliaries (the non-citizen infantry and cavalry of the regular armies of the Roman Empire), amphibious units requiring armed swimming were the least popular, but citizens who could not join the legions, such as Trentianus, were accepted. In addition to the dangers of swimming, the land tasks of this unit were also arduous, including road construction, firefighting, and guarding Rome's food supply.

With certain social relationships, soldiers will be transferred to units with better treatment (such as cavalry), or units where they can learn useful skills (such as carpentry). Otherwise, you can only rely on promotion. Soldiers who were promoted had to be men of ability, and only those who could do arithmetic and literacy were given the coveted role of accounting flag bearer, who was paid twice as much as a regular soldier.

The cavalry is the most enviable branch of the army. They receive extra pay to maintain the horses and their equipment, are assigned fewer chores, and have the opportunity to participate in spectacular parades.

combat attire

Soldiers must purchase and maintain their own weapons and armor. New or second-hand equipment can be purchased at the fort armory, sometimes from local craftsmen. Some veterans pass their used weapons on to the next generation. Old weapons can also be modified or updated by a blacksmith.

Bronze helmet, Germany, 10 BC-30 AD, British private collection

A helmet from Germany's Eich is in a similar situation. Its original form appeared in the early 1st century AD, but was modified to fit the style of helmet design half a century later - Roman blacksmiths reshaped the neck protector and added carrying handles. Another helmet in the exhibit bears the names of four soldiers, suggesting it may have been in use for as long as a century. However, after modification, Ashe's helmet bears only the name of one owner: "Marcus Arruntius of Aquileia, Italy, who served under Sempronius."

camps and activities

Soldiers go through a lot of hard life before they go to war. It included months of marching and night camping; eight soldiers sharing a tent and sharing camp duties. Tents were temporary residences for soldiers, emperors, and sometimes even empresses. Julia Domna was the wife of the Emperor Septimius Severus. She was famous for accompanying her husband on military campaigns. She was so beloved by the soldiers that she was awarded the "Mater Castorum" (Barracks). mother). The bust shows off her distinctive hairstyle, which was a wig with a curve at the back that made it look like a helmet, perhaps intentionally showing off her connection to the military.

Marble portrait of Julia Domna, probably Italy, 203-217 AD

Roman legions deployed highly organized battle lines and shield walls. Their tactics and formations allowed them to face the overwhelming heavy assault cavalry (Carthaginian cavalry) coming from the east. The Carthaginian cavalry wore full body armor (both human and horse). This armored horse rug, found at the site of Dura Europos in modern Syria, used scales larger than those found on human armor. Dura Europos was an important trading center at the time, but was destroyed by the Sassanids in 256-267 AD.

Cataphract armor (iron, linen and leather), Syria, 200s AD

fortress life

Roman armies built forts where they might need long-term garrisons—along the borders of the empire or in restless areas to prevent local uprisings. Their standardized design was similar to Roman towns, but included barracks and other military buildings. Outside the city walls civilian towns emerged with bathhouses, shops and taverns. Soldiers can enjoy a private life with their families outside of military duties. Objects related to domestic life and even leisure time are common in the fort, such as a sandstone game board and glass chess pieces from Vindolanda.

Sandstone game board with glass parts, Vindolanda, 85-410 AD

Ordinary soldiers (centurions and below) were not officially allowed to marry, but they still formed de facto families with women. Enslaved men, women, and children also lived in the forts, and some even traveled with the soldiers. Evidence of women, children, and enslaved populations associated with the military is common in fort and tomb images. The tombstone is that of the daughter of Crescens, an imaginifer (a form of Roman standard-bearer), and the relief depicts her reclining on a sofa with a young The slave maid is servicing her. The names of servants are rarely recorded, and the names of Crescents' daughters do not remain on tombstones, so both women remain nameless.

Tombstone of a Standard Bearer's Daughter, England, 100-300 AD

One of the most striking evidences of family habitation in the fort is the many shoes from Vindolanda belonging to men, women and children. The exhibition features a pair of tiny leather children's shoes.

Ruins of the fortress and garrison settlement in Vindolanda, 2023

occupation enforcer

Rome conquered and assimilated an unprecedented vast territory. The people of these territories (provinces) were subject to Roman law, and soldiers were responsible for enforcing these laws and establishing punishments. A limited number of soldiers were required to maintain a vast empire, which could lead to oppressive and exploitative control. As law enforcers, Roman soldiers were naturally unpopular and could face the danger of reprisal. Regimental rolls may list soldiers killed by "bandits."

Although large-scale rebellions are sporadic, when they occur, they often cause huge casualties to the army and local people. In AD 9, Arminius, the son of a Germanic tribal leader who had been appointed commander of the Roman cavalry, led a revolt against Roman rule. Working with native tribes, he destroyed three full Roman legions in the Teutoburg Forest. More than 40 years later, in Britain, Boudica, queen of the Isini tribe, led a less successful uprising that led to new Roman settlements including St. Albans, Colchester, and London. Points were burned.

One piece of armor on display is the oldest and most complete Roman segmented cuirass ever found, a form of body armor often found on legionnaires like those depicted on the Traianus Column. Found in the Teutoburg Forest, it is believed to have belonged to soldiers killed in the Arminian Rebellion. The skeleton of the wearer is long gone, but the almost skull-like form of this flexible yet strong Roman armor is reminiscent of the individuals who perished in the revolt.

Nearly complete Roman segmented armor, Calcresse, Germany, 9 AD

Retired

At the end of the exhibition, the life of soldiers after retirement is explored. It is estimated that about half of all soldiers survive disease and violence until retirement. Citizen-soldiers would receive generous bonuses upon discharge, enough to buy land or live a comfortable life.

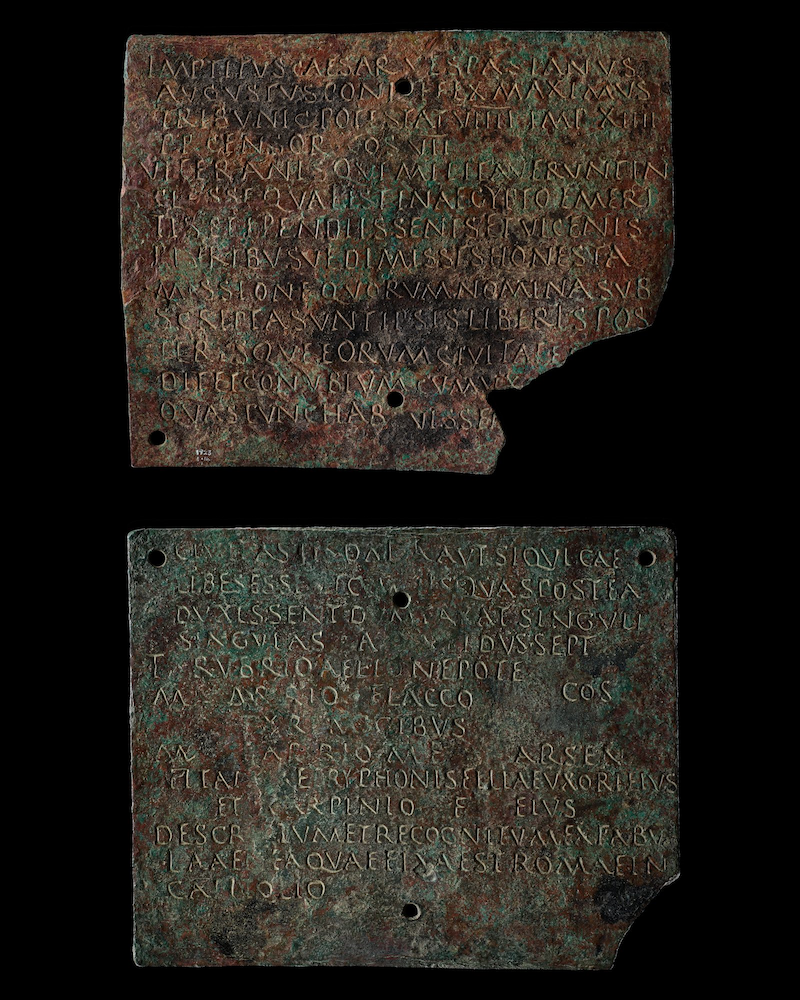

Retired auxiliary soldiers will be granted citizenship, the beginning of a social transformation for them and their families. As proof of this status, they were given a copper certificate - portable and durable. The example in the exhibition belongs to a fleet oarsman named Marcus Papirius. Roman oarsmen were free men, and after many years of service Papirius, his wife Tapaea, and son Carpinius were granted citizenship.

Bronze decommissioning certificate, Egypt, 8 September 79 AD

Note: The exhibition will run until June 23. This article is compiled from the British Museum website and the exhibition review "More than a bloody orgy of Roman military power" by Jonathan Jones in The Guardian