"Glorious Times: Spanish Past in the Prado Museum" is currently being held at the Shanghai Pudong Art Museum. The exhibition spans the 16th to 20th centuries and brings together 70 works by painters such as Titian, Veronese, El Greco, Rubens, Velázquez, Goya, Sorolla and others from the Prado Museum's collection. Among them, one can see the inheritance of Spanish painting and it is also a witness to the science, economy, culture and other aspects of Spanish history.

The 70 works have revealed a small part of the Prado Museum’s collection. Miguel Falomir, director of the Prado Museum, recently accepted an exclusive interview with The Paper in Shanghai. In his opinion, the Prado Museum’s collection has both aesthetic and historical significance, reflecting the Spanish royal family’s preference for color over form. It also has a large number of works by Titian, Rubens, Velázquez, Goya and other masters, which makes the collection show a self-referenced correlation, showing the mutual learning and reference between painters.

Interior of the Prado Museum

The Prado Museum in Madrid, Spain, was founded in 1819 and inherited the royal collection. In the late 19th century, it was known as one of the "four major art museums in the world." Although its collection grew slowly due to the political turmoil in Spain in the 20th century, it was gradually surpassed by many museums in terms of total volume. However, the number of masterpieces owned by the Prado is unattainable by later museums.

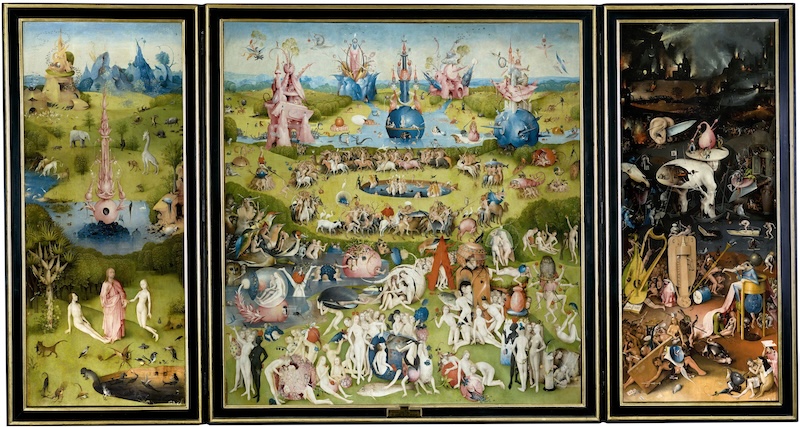

The Prado also has works by Michelangelo and Raphael, two of the "Three Masters of the Renaissance". The Spanish section of the collection is unparalleled in the world, and it is the museum in the world that has the most works by Velázquez and Goya. In addition, the Italian and Dutch sections are also irreplaceable, with a number of rare masterpieces that are rare in their own countries, especially the works of Bosch. This is due to the appreciation and extensive collection of Bosch by King Philip II of Spain during the Habsburg dynasty. In addition, the works of masters such as Titian, Rubens, Dürer, Botticelli, Veronese, and some other Italian and Greek painters during the Renaissance, together constitute the Prado's collection.

The main entrance of the Prado Museum, with a sculpture by Velázquez in front of it.

Miguel Falomir, the current director of the Prado Museum (born in Valencia in 1966), holds a doctorate in art history. Since 1997, he has been the head of the Italian and French Renaissance Painting Department of the Prado Museum. During this period, he has curated many exhibitions, including Titian (2003), Tintoretto (2007), "Renaissance Portraits" (2008), "St. John the Baptist" (2012), and "Titian's 'Poem' for Felipe II" (2014), etc. He also participated in the restoration of important works by Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese and Raphael. He has been the deputy director of the Prado Museum since June 2015, and the director since 2017. The Paper's exclusive interview with him starts with his dual identity as an art historian and curator:

Miguel Falomir, director of the Prado Museum

On Art History Research

The Paper: You are an art historian and have been the director of the Prado Museum since 2017. Does your identity as an art historian indicate that the Prado Museum focuses on academics? Among the many collections of the Prado, which research directions do you focus on?

Falomir: Of course, I am first a scholar. I started studying European art when I entered university at the age of 18. In 1998, I entered the Prado Museum to do relevant work; since 2017, I have served as the director of the Prado. From a personal perspective, I have not been doing management work for a long time. My identity as a scholar and my vision have always influenced or restricted some of the work of the director. Therefore, I and the Prado team I lead attach great importance to the study of art history.

Research is one of the important functions of a museum. Since I took office as director, I have gathered a new generation of art history research experts from all over the world and continuously explored the potential of the Prado Museum as an art history research institution.

Jan Bruegel the Elder and Rubens, "Taste", 64×108cm, circa 1618, from the collection of Philip IV (not on display in this exhibition)

One of the more important research directions, which is also what we are doing now, is to conduct in-depth and systematic research on the Prado collection and record it in the form of publication. In just a few months, we will publish a research catalogue on the works of the Flemish School of Painting in the 16th century, which is also one of the more important research directions of the Prado. In addition, there are some other research focuses that have always been the Prado Museum. For example, how did these works enter the Prado collection? That is to say, the source of the collection works, or what is their origin, what kind of circulation and collection process have they gone through, and who donated them to the Prado Museum.

Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, c. 1510, acquired since 1939, from the collection of King Felipe II (not on display in this exhibition)

Another focus of the study is the contribution and status of women in the Prado collection and the Prado Museum. The Prado Museum may be the most prominent museum in Europe for women. Among the 70 works exhibited in Shanghai, 4 were created by female painters. In addition, the construction of the Prado Museum was proposed by the Queen, so the contribution made by women of the Spanish royal family in the establishment of the Prado Museum, as well as the role and status of women, is also one of our current research focuses.

Sofonisba Anguissola, "Elizabeth of Valois holding a portrait of Philip II", 1561-1565, oil on canvas, from the royal collection (Royal women painted by female artists in this exhibition of the Pudong Art Museum)

In addition, how does the Prado collection present itself in a larger context (such as the entire history of European painting) or the background of the times? Or how does the relationship between the collection and the big history present itself? This is also what we are concerned about.

The Paper: Which piece or pieces of work in this exhibition do you think are the most comprehensive? What stories of Spain and art do they tell?

Falomir: The Prado Museum is closely related to Spanish history. In this exhibition, "Filipe II on Horseback" and "Filipe IV in Hunting Costume" can be used as key works to tell the story.

The exhibition "Glorious Times: Spanish Past in the Prado Museum" at the Pudong Art Museum, with Rubens' "Philip II on Horseback"

Why is it so important? Not only the status of the people and the painters in the paintings, but also the value of the paintings themselves. Secondly, it tells the history of Spain like a documentary or archive. Felipe II and Felipe IV played a very important role in the Prado's collection. Felipe II bought and commissioned a large number of works by Titian, and Felipe IV also had such a relationship with Rubens and Velázquez.

Diego Velázquez, "Felipe IV in Hunting Costume", circa 1632-1634, oil on canvas, Museo Nacional del Prado

In addition, the same is true of Goya's two paintings presented in the "Bourbon Dynasty and the New Regime" exhibition area. As a court painter, he painted portraits of royal family members, which not only tell the story of the royal family, but also the status of the people in the paintings and their relationship with the people. The artistic quality of the paintings themselves is also very high.

So I think these works are a combination of Spanish history and art history, with both aesthetic and historical documentary significance.

The exhibition "Glorious Times: Spanish Past in the Prado Museum" at Pudong Art Museum, with Goya's works on the left

The Paper: The Prado Museum has many works by artists in its collection, such as Titian, Veronese, El Greco, Rubens, Velázquez, Goya... How do their works reflect the heritage of Spanish art?

Falomier: Most of the collections of the Prado Museum come from the royal collection. The royal collections come from the tastes of the monarchs, and they are not academically considered. When scholars try to build museum collections, they always hope to include all periods and include as many painting genres and styles as possible in an encyclopedic way, as well as as many works of famous artists as possible. But royal collections are different. As monarchs, they pay attention to the works they are interested in, so they will try to buy all the works they like and think are beautiful. It is for this reason that in the Prado's collection, you can see the monarch's aesthetics and passion, and this interest has continuity in the royal family, even for several centuries.

Titian, "Venus and Adonis", 186×207cm, circa 1553-1554, from the collection of Philip II (not on display in this exhibition)

The exhibition site of "Glorious Times: Spanish Past in the Prado Museum" at Pudong Art Museum, from Rubens and his studio "The Rape of Hippodamia" studio

For example, after the 16th century, these monarchs preferred to collect works that focused on color (colorare) rather than shape (disegno). In the Prado's collection, the preference for color before line is presented and continued, and it has a huge influence. Among the painters you just mentioned, Rubens and Velásquez both learned from Titian, and later Goya learned from Velásquez and the works of past painters to form his own style. The Prado Museum has a large number of works by these painters, so it can have such a self-reference - painters learning and borrowing from each other.

Titian's work "Venus in Love and Music" is exhibited in the "Myth of the Secret Chamber" exhibition hall of the "Glorious Times: Spanish Past in the Prado Museum" at the Pudong Art Museum

Goya, "The Dressed Maja", 95×190cm, circa 1796-1798, collected since 1901, from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando (not on display in this exhibition)

The Paper: Michelangelo and Titian had different views on lines, and their differences were also reflected in the styles of the works of the Florentine and Venetian schools. How do you view their differences and the subsequent debates? How did the Italian Renaissance spread to Spain?

Falomier: This debate may have separated the issue of line and color too much, and it is actually a binary issue. Of course, a better way is to combine them - Titian's colors and Michelangelo's lines. On this issue, the Prado Museum has a very important painter, Tintoretto, whose paintings may well express this point. According to legend, he aspired to "paint like Titian and design like Michelangelo", which may be the most perfect state. But the royal family at that time (that is, the Spanish collection at that time) believed that color might be more important, so in the Prado collection, and even in Spanish paintings, the characteristics of color before line are reflected.

Tintoretto, Joseph and Potiphar's Wife, 1555, Prado Museum. Velázquez bought this painting and five other biblical paintings for Philip IV of Spain to decorate the ceiling during his second visit to Venice. (Not on display in this exhibition)

Because of the royal family's preference, the Venetian School had a much greater influence on Spanish painting than the Florentine School, especially Titian's painting style in the Venetian School. Art critics once called Titian's painting style "pointillism", which means that you may have to be farther away from the painting to see its full picture. The Florentine School's painting style is more linear and clearer.

Titian, Self-Portrait, 86×65cm, circa 1556, acquired in 1821, from the collection of Philip IV (not on display in this exhibition)

Before the Venetian School, the Flemish School had influenced Spanish painting earlier, especially in the 15th century, when many Spanish-Flanders painters were obviously influenced by the Flemish School, although there was no Spanish or Italian school at that time. But in the 16th century, the presence of Italian painting became stronger and stronger, and Spain and Flanders began to imitate and learn Italian painting, and the trend of Italian art centralization began to emerge.

Mantegna, Death of the Virgin, 54×42cm, 1460, from the collection of Philip IV (not on display in this exhibition)

The Paper: In the Prado Museum, El Greco and especially Velázquez's "Las Meninas" have been repeatedly studied and interpreted by modern Spanish artists such as Picasso and Dali. Can you talk about their previous inheritance and how it has been passed down to the present day?

Falomir: I think the Prado Museum has a huge influence on modern European art. For example, in the 18th century, when the French Impressionists were determined to reform their painting methods, they used color before lines as an important means of expression. The Prado Museum is obviously of great significance to the development of art.

Velázquez, Las Meninas, 318×276cm, circa 1656, acquired in 1819, from the collection of Felipe IV (not on display in this exhibition)

Not only Impressionism, but also German Expressionist painting may not be understood without looking at El Greco's works. The rediscovery of El Greco's paintings in the late 19th century and early 20th century had a profound impact on 20th century European modern art.

At the exhibition site of "Glorious Times: Spanish Past in the Prado Museum" at the Pudong Art Museum, the first one on the left is a work by Veronese, and the two on the right are works by El Greco, which shows the influence of Veronese on El Greco.

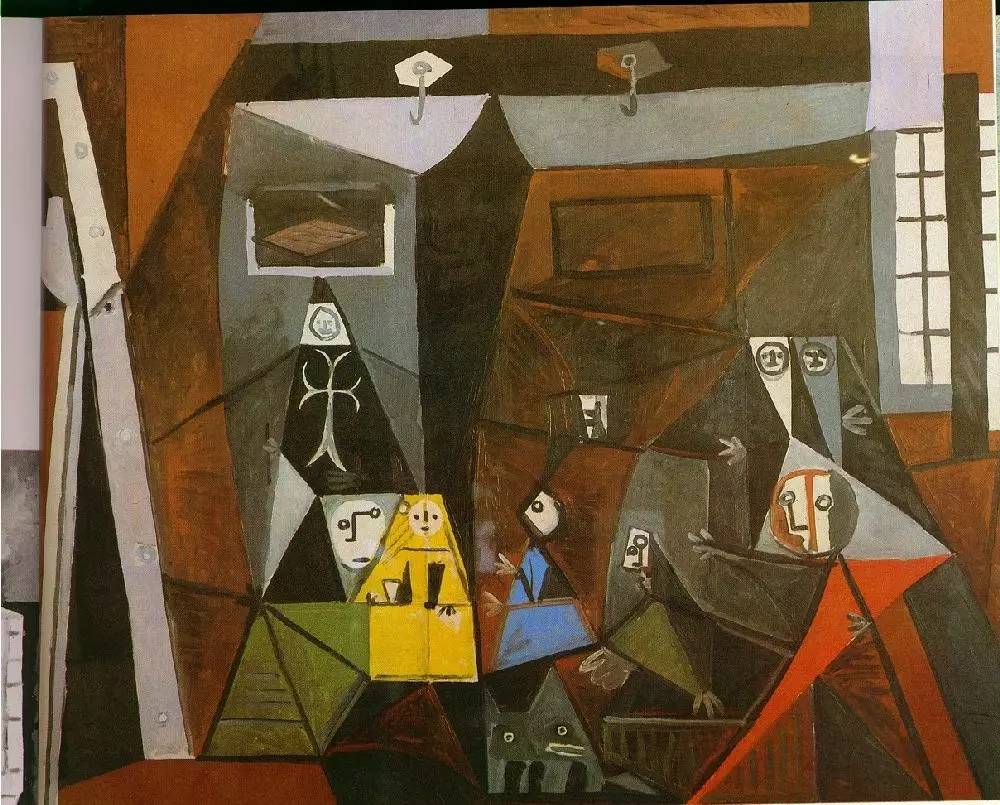

As mentioned above, Picasso was influenced by Velázquez, and he imitated Las Meninas a lot. In addition, Velázquez also had a profound influence on Francis Bacon. Bacon died in the Ritz Hotel in Madrid because he wanted to be closer to Velázquez's works.

Picasso, Las Meninas, 129x161cm, 1957 (not exhibited in this exhibition)

The main entrance of the Prado Museum, with sculptures by Velázquez

The Paper: What kind of project is the "Invited Work" currently being carried out by the Prado Museum, and what role does it play in the study of the Prado's collection and European art history?

Falomir: I think this is a very good project. The so-called "invited works" are mainly to hope that the collections of other museums will have a dialogue with the Prado's collection. For example, the current "invited work" "Still Life with Citron, Orange and Rose" (exhibited in Room 10A of the Prado Museum until June 30) comes from the collection of the Norton Simon Museum in California. It is the only signed and dated still life painting by Francisco de Zurbarán in existence. This painting is special and we also hope to use it as a supplement to Zurbarán's painting themes.

Exhibition site of "Invited Works" "Still Life with Citron, Orange and Rose" (March 18-June 30, 2024)

Center: Zurbarán, Still Life with Citron, Orange and Rose, 1633, this is the only still life painting signed by Zurbarán and one of very few works in this genre known to have been created by him. The unbroken tradition of the Spanish still life genre can be recognized through research and study.

Zurbarán, Still Life, 46×84cm, circa 1633, from the collection of the Prado Museum (not on display in this exhibition)

Pudong Art Museum’s “Glorious Times: Spanish Past in the Prado Museum” still life painting exhibition hall.

We will also invite some Impressionist works and display them together with the works of masters who influenced them, so that the audience can see the connection between Impressionist paintings and the Prado collection; we have also invited 15th-century French paintings for a dialogue-style exhibition.

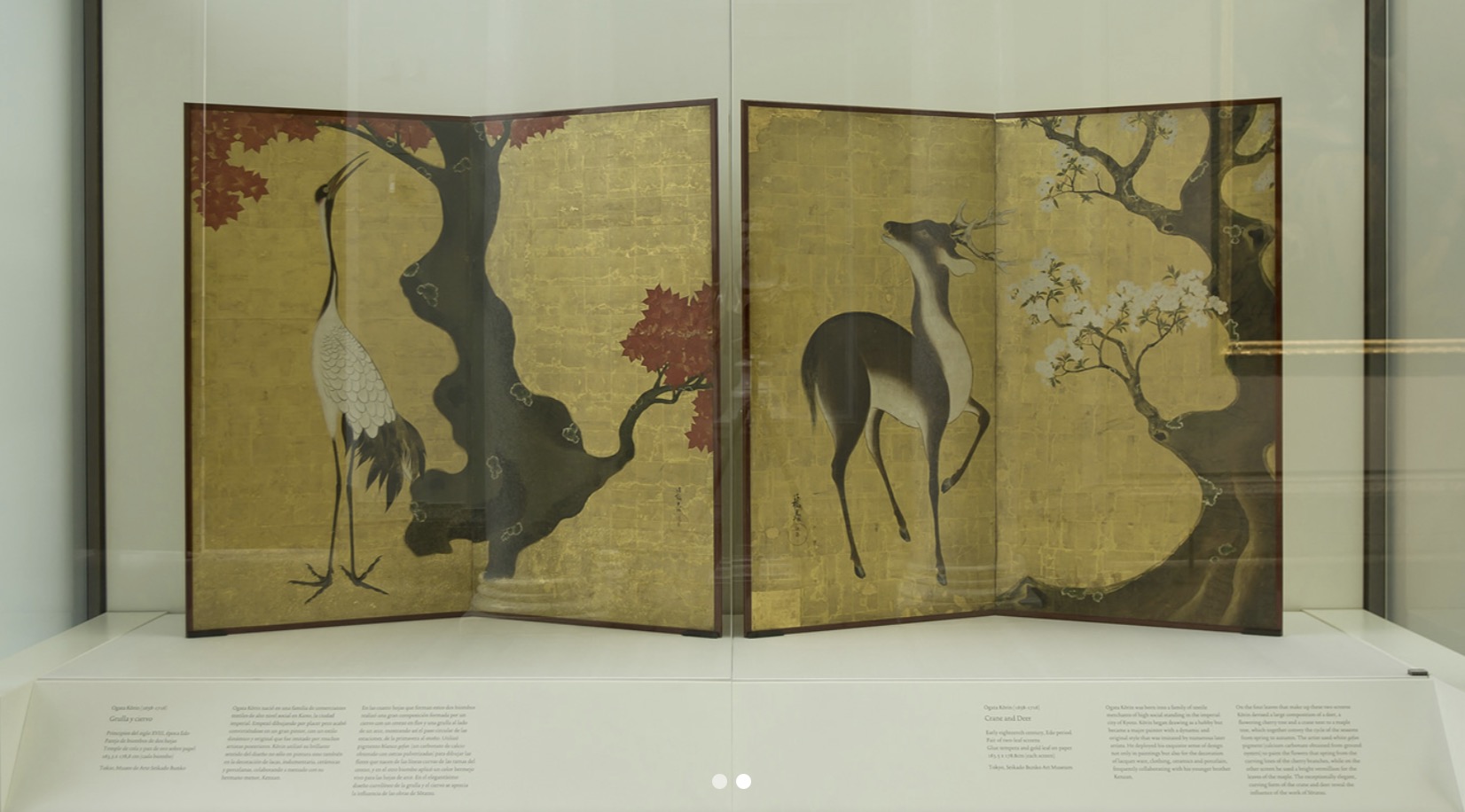

Among the “invited works”, I was personally most impressed by two pairs of 18th-century Rinpa screens from the Seikado Bunko Library in Tokyo and the Tokyo National Museum. They contrast sharply with the works in the Prado collection, and this contrast also makes the conversation interesting.

(Note: The Prado’s “Invited Works” project began in 2009, with Georges de La Tour’s work “The Penitent Magdalene” from the Louvre.)

Ogata Kōrin, "Deer and Crane Folding Screen", early 18th century, Edo period, Seikado Bunko

About Museum Operations

The Paper: Many museums in Europe are facing some controversies now. As for the Prado Museum, how does it deal with these controversies?

Falomier: Indeed, there are many problems that need to be faced at present, but some of them may not be called problems, because society is always progressing and changing, and museums also need to face them, or in other words, facing a room full of works by dead painters, how can museums keep up with the progress of the times? Museums must of course use their own ways to attract new groups, look at some of the collections with new eyes, and give these works new value.

The Prado Museum in the 18th century as depicted by Italian painters

Although there is no problem of theft or violence in the Prado's collection, some social issues do affect us. For example, the whole society pays attention to the status of women. I mentioned it before. We also have corresponding projects to focus on this. Of course, there is also the issue of racism. In fact, racial issues have arisen in the 19th century. When Spain was still the sovereign of some Latin American countries, the works of Mexican and Peruvian painters were exhibited in the same place as the works of so-called European painters.

Prado Museum Exhibition Hall

But after the 19th century, due to the influence of nationalism, painters from the New World were no longer viewed in the same light, and were not even considered to have equal artistic value, but rather more anthropological value, so these paintings were transferred to anthropological museums for exhibition.

The Prado Museum is now also working hard to look at this issue of "de-Europeanization" again, allowing works from New World painters of the same period and with the same artistic value to return to the collection and regain the importance they deserve.

The Paper: What do you think about the current trend of de-Eurocentrism in the field of art history research, and the fact that many exhibitions in recent years have focused on dialogues between different cultures?

Falomir: I think the world started the process of globalization earlier than we realized. How to think about and reposition the entire European art in a larger and more global context and perspective is very important for museums, European history and art history research.

It is very meaningful for different cultures to have parallel dialogues in exhibitions, but I don’t like all such exhibitions. “Dialogue” exhibitions require the curator’s vision to make parallel comparisons of artworks from different or same periods and far away. Some comparisons are meaningful, but if the curator’s academic ability is not enough, such comparisons may seem meaningless.

I think as scholars, we need to look at cultural dialogue, communication and comparison from a broader perspective, including culture, art schools, painters, and paintings. Some are similar or related, but some may not be found directly, which depends on the curator's skills. For example, if Bacon and Velásquez are compared, I think it is meaningful, because there is obviously influence and inheritance between them, but in some exhibitions, the painters may not be well-known or there is no relationship between the painters, so such exhibitions are not very meaningful.

Prado Museum Exhibition Hall

The Paper: The Prado Museum also faces different types of audiences, including professionals, tourists, and community audiences. How does the Prado handle the relationship between these audiences? What is the relationship between the Prado Museum and its community (or community)? Including projects such as "Signar con el Prado: A Glossary of Art and Museum Concepts" (Signar con el Prado), how can more people understand the Prado and art history?

Falomir: Obviously, as a museum that may receive 3 million or more visitors every year, we are well aware that they come from different social classes. Some are elite and very professional, but many are not. For this reason, the Prado has launched a series of projects to serve the needs of different groups of people.

Recruitment for projects for children on the Prado website.

Recruitment for summer courses for young people on the Prado website.

For example, one of our most professional public education projects is the Latin guided tour. Strangely, this project is always fully booked, which means that there are many people who have reached such a professional level. Of course, there are also projects for women in remote areas, rural residents, and even prisoners, so from the most elite to the most popular, it covers almost all groups.

In addition, we also brought touch-sensitive exhibits to serve the visually impaired, such as the "Mona Lisa" from the Prado, and provided sign language interpretation for some of the museum's series of lectures. We hope to have a diverse presentation of the museum's visual instructions, exhibition labels, and educational materials.

The Mona Lisa can be touched at the exhibition "Glorious Times: Spanish Past in the Prado Museum" at the Pudong Art Museum

Including the project "Symbols of the Prado", there are some specialized terms in the field of art. We are now studying how to express them in a symbolic way, including sign language. We hope to have new presentations and new discoveries.

"Signs of the Prado" was born out of a collaboration between the Prado Museum and the CNSE Foundation, which aims to expand the Spanish Sign Language dictionary with specific terms in the semantic field of art and museums.

The Paper: Madrid’s famous “Golden Triangle of Art” covers the Prado National Museum, the Reina Sofia Center for Contemporary Art and the Thyssen Museum. What is the positioning and cooperation of these three museums?

Falomir: From the perspective of art collection, all three are national museums. The Prado’s collection is more classical and master-level; the Reina Sofia Art Center is more modern art, and the Thyssen Museum is encyclopedic, which may cover a longer period of time and more countries. The Thyssen collection is a very good supplement to the Prado and Reina Sofia Art Center. For example, perhaps because of the war, the Prado Museum has fewer works by Dutch painters, but the Thyssen has a lot, including Rembrandt’s works. The relationship between the three of us is really very good, so much so that all three have tickets for sale.