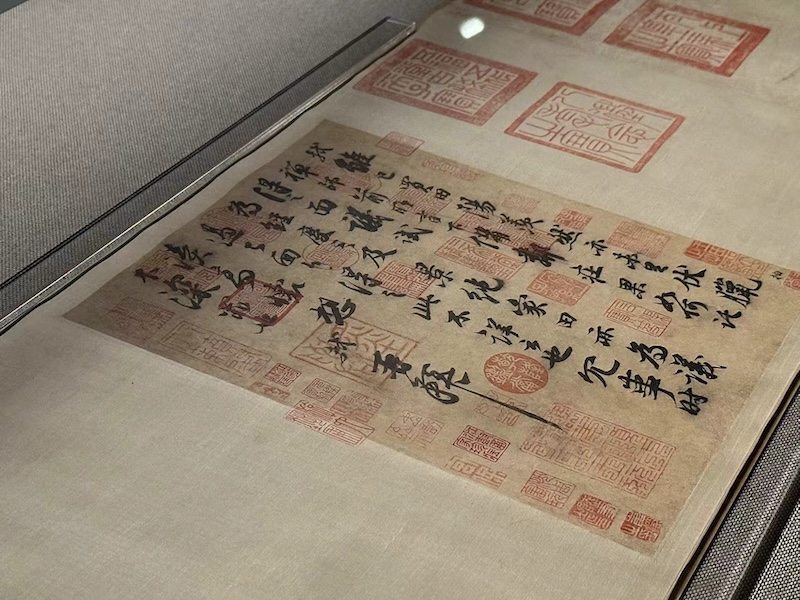

There is a Su Dongpo in everyone's heart. In literature, he is one of the "Eight Great Masters of the Tang and Song Dynasties", leaving poems and articles that have been passed down for thousands of years; in calligraphy and painting, he, Huang Tingjian, Mi Fu and Cai Xiang are collectively known as the "Four Masters of the Song Dynasty". "Han Shi Tie" was written with emotion and full of desolation.

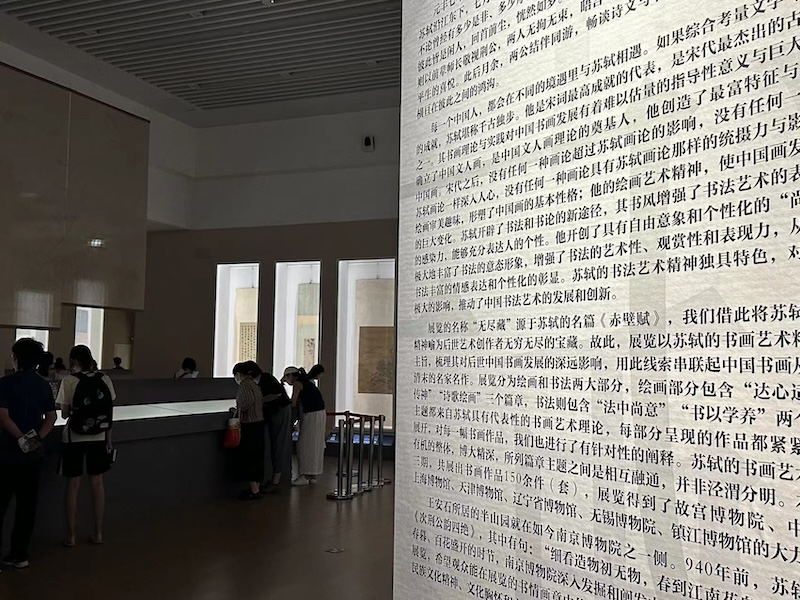

In recent years, many major exhibitions with the theme of Su Shi have been held in China. The "Endless Collection - The Artistic Spirit of Su Shi's Painting and Calligraphy" currently being held at the Nanjing Museum is huge in size and themed "The Artistic Spirit of Su Shi's Painting and Calligraphy". It is said that after After three years of polishing, to be honest, there are quite a few paintings and calligraphy works. In terms of quantity, they are certainly worth seeing. However, among the more than 150 works, only "Zhi Ping Tie" is a calligraphy work by Su Shi. The authenticity of "Xiaoxiang Bamboo and Stone Pictures" has always been doubtful, and the former was replaced in June. One impression is that for this exhibition, "Su Shi" is just a name and symbol. After viewing the exhibition for more than ten minutes, the author almost forgot that this was a "Su Shi exhibition."

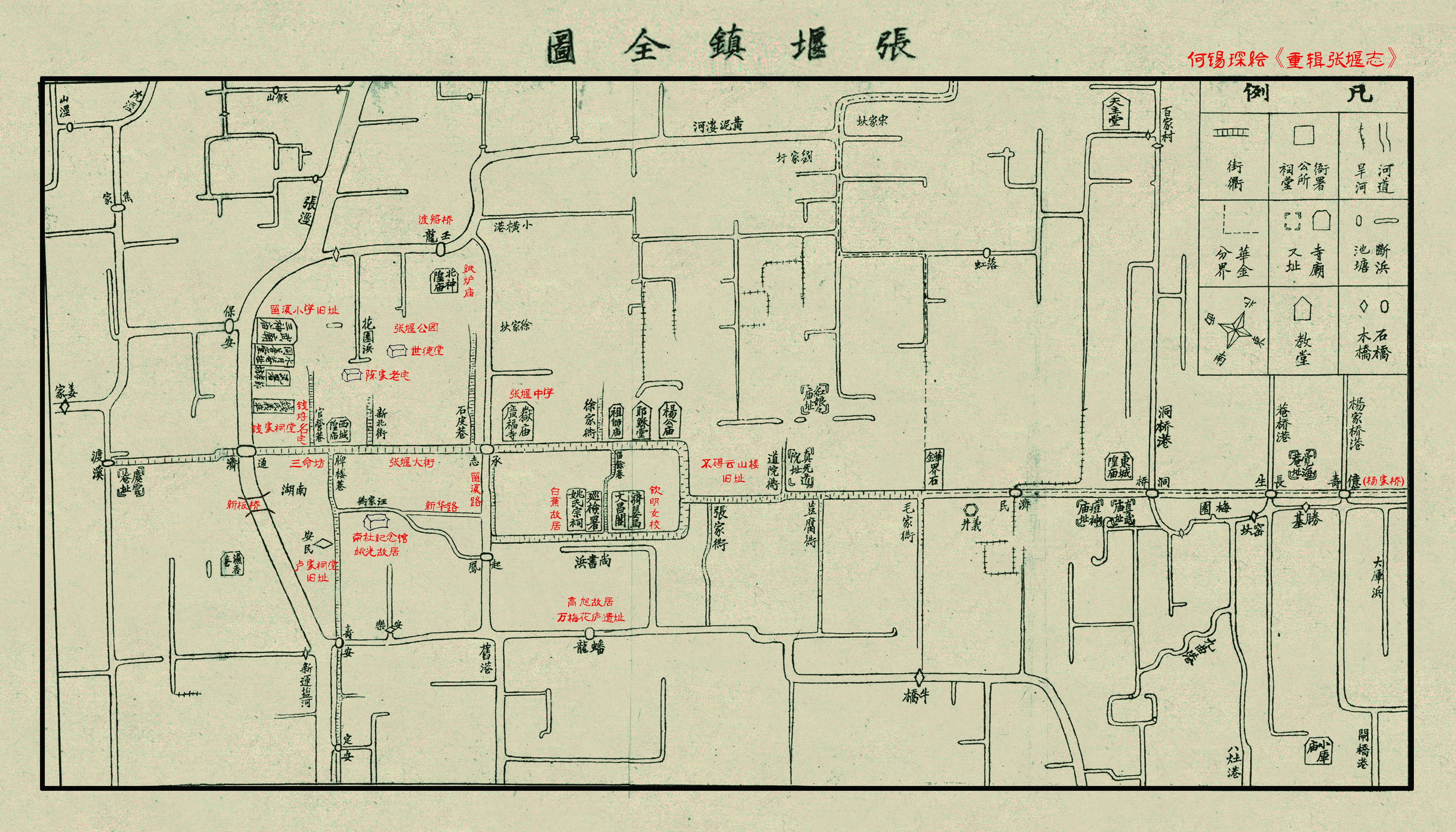

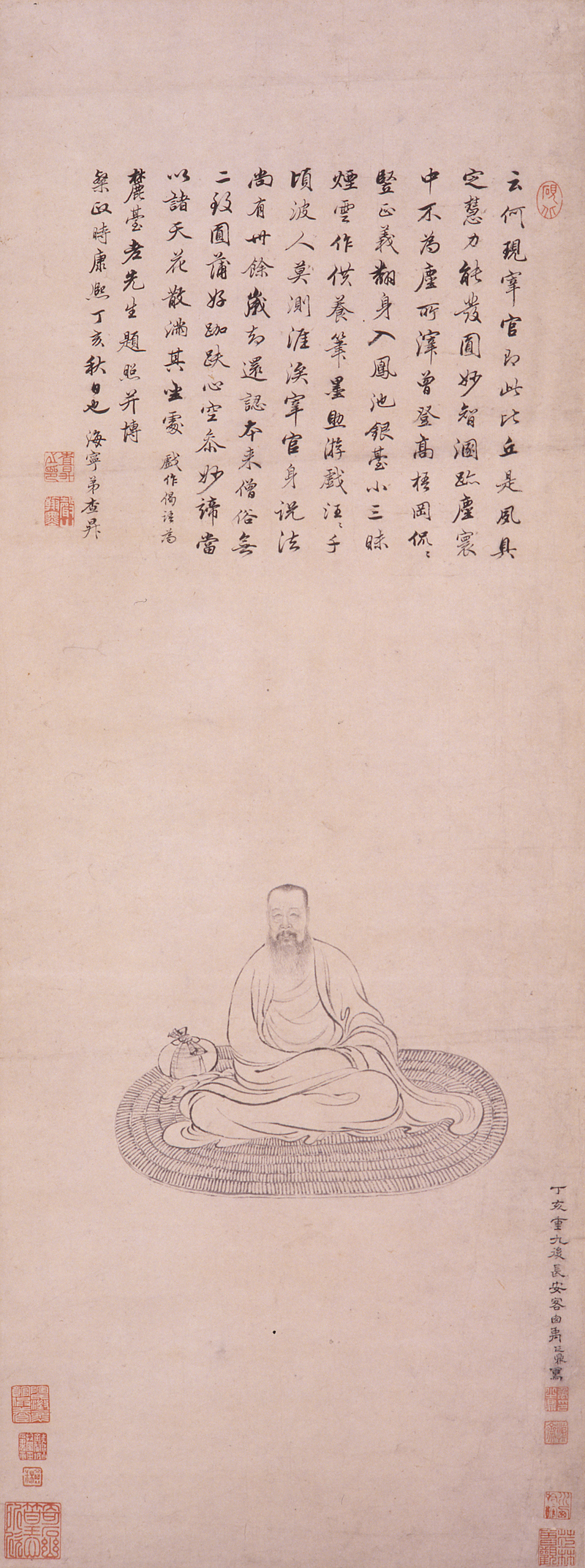

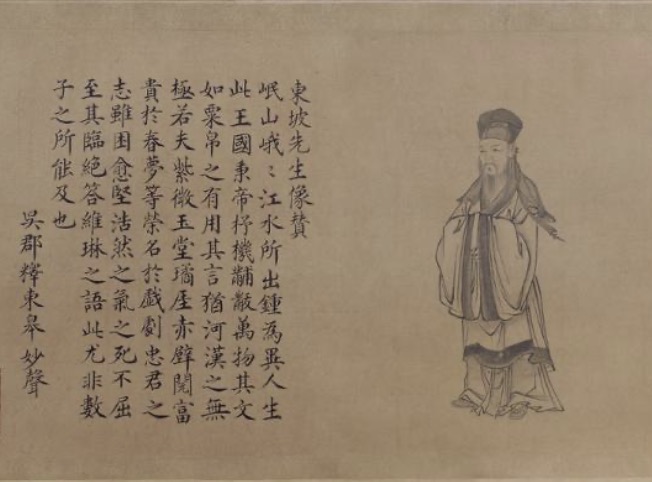

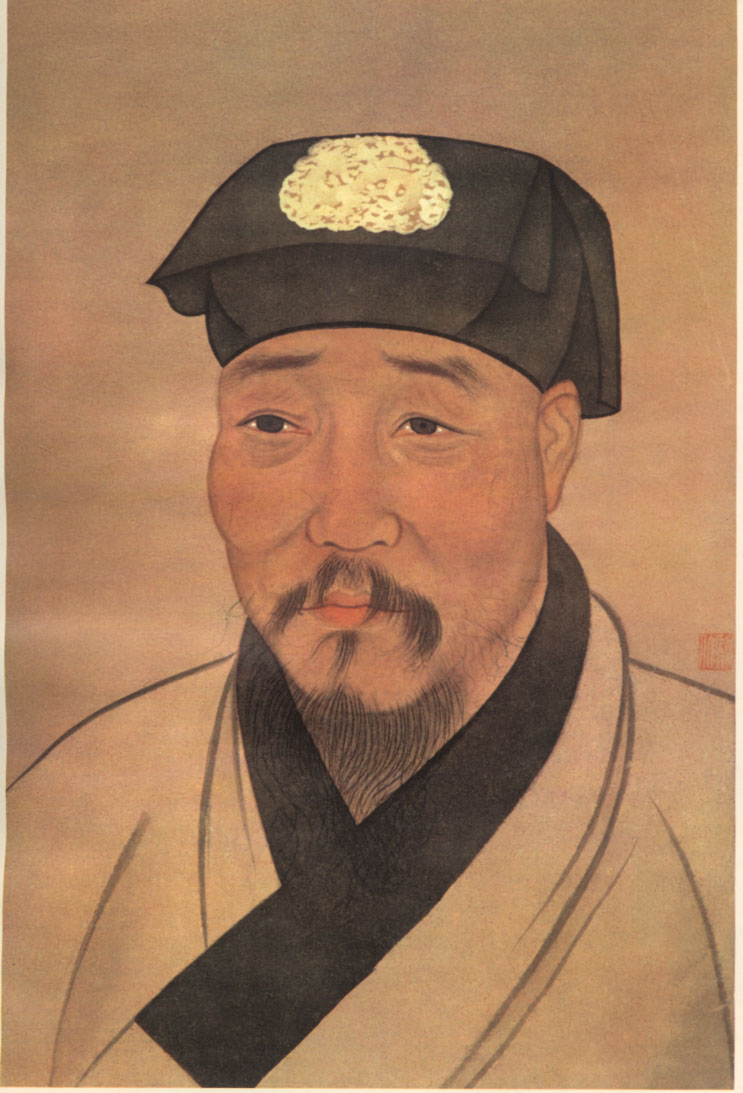

Su Shi's running script "Zhi Ping Tie" (collected by the Palace Museum) introduces the portrait of Su Shi painted by the Ming Dynasty and the "Praise to the Portrait of Mr. Dongpo" written by Shi Donggao Miaosheng. (Works exhibited in the first phase of "Endless Collection - Su Shi's Artistic Spirit of Calligraphy and Painting" held at Nanjing Museum)

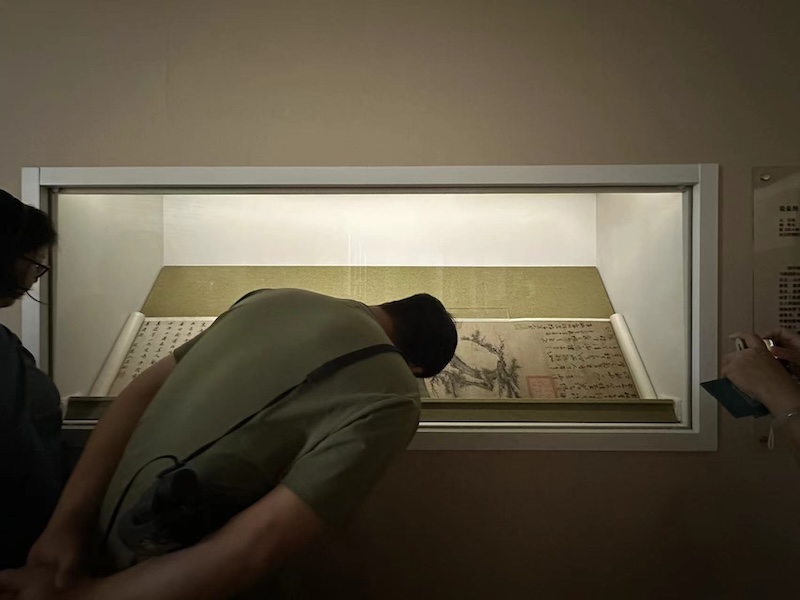

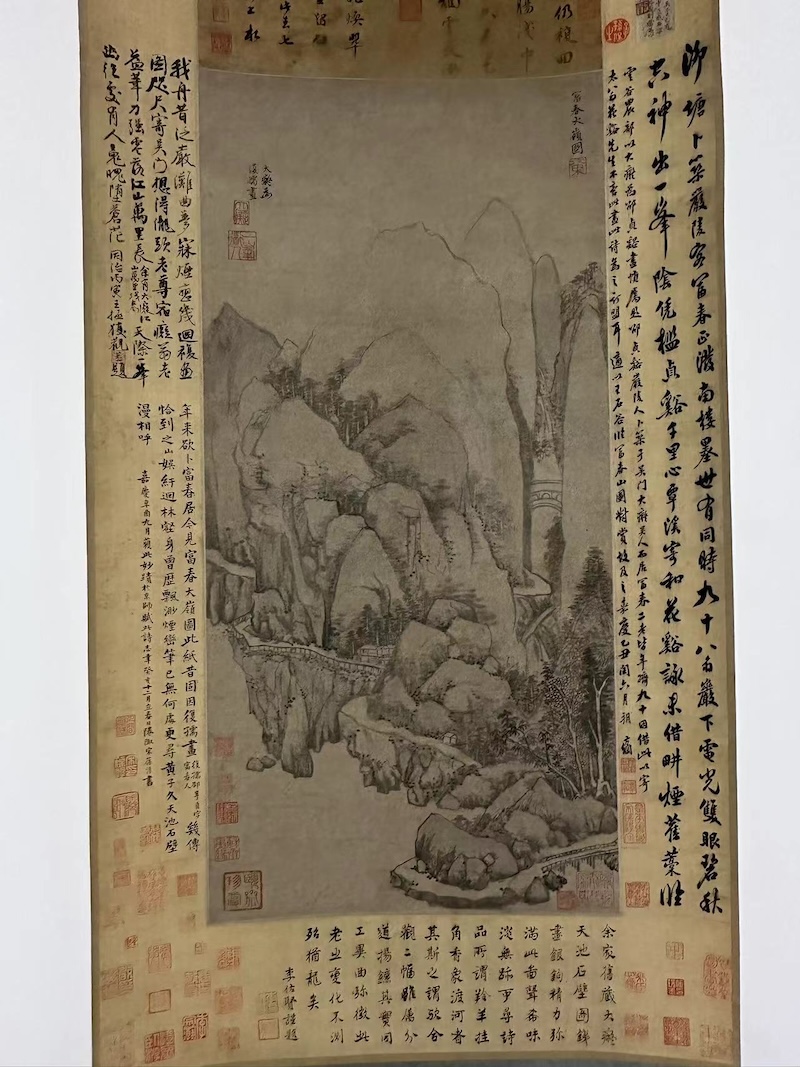

The author rushed to grab admission tickets to Nanjing Museum a week in advance, and then purchased tickets for special exhibitions ( in my impression, among domestic provincial and municipal museums holding ancient Chinese calligraphy and painting exhibitions, it seems that only Nanjing Museum has been "unconventional" in insisting on charging ), and finally caught up. The last train of the second period. However, when walking into the exhibition hall and facing the first exhibit, "Pine Spring Picture" by Wu Zhen of the Yuan Dynasty (collected by Nanjing Museum), I had to bend my waist and lower my head - why stand the scroll and display it in the form of a hand scroll? I originally thought I would focus on the inscription and postscript on the left side, but then I looked at the long text annotation, which tells about the "Pine Spring Picture" itself and the cursive script inscription on Wu Zhen's painting.

The first exhibit in Nanbo's Su Shi exhibition is "Pine Spring Picture" from Wu Zhen in the Yuan Dynasty. The vertical axis is placed horizontally, causing viewers to bend their waists frequently.

If in the mid-20th century, Western modernist artists as "laymen" used the lines of Chinese calligraphy and painting as an abstract pattern, this vertical axis may be understandable, but in the face of Chinese audiences who can interpret it (including many professionals) , this way of display really makes people unable to grasp the curatorial intention. However, as the exhibition progressed, I gradually realized that this is a popular calligraphy and painting exhibition for the public. Among the more than 150 works, only "Zhi Ping Tie" is a calligraphy work by Su Shi, and "Xiaoxiang Bamboo and Stone Pictures" has a larger presence. controversial work, and the former was removed in June. Is "Su Shi" just a name and symbol? After viewing the exhibition for more than ten minutes, the author had already forgotten that this was a "Su Shi exhibition."

According to official information, the exhibition is based on five representative calligraphy and painting art theories derived from Su Shi: "expressing the heart's comfort", "writing to express the spirit", "poetry and painting", "suggesting meaning in law" and "cultivation through learning". Each painting and calligraphy The works have been given targeted explanations (the exhibition text amounts to hundreds of thousands of words), and it is believed that "Su Shi's artistic spirit of calligraphy and painting is an organic whole, broad and profound, and the topics listed in the chapters are integrated with each other, not distinct. "So, how does the exhibition explain Su Shi's artistic spirit of calligraphy and painting?

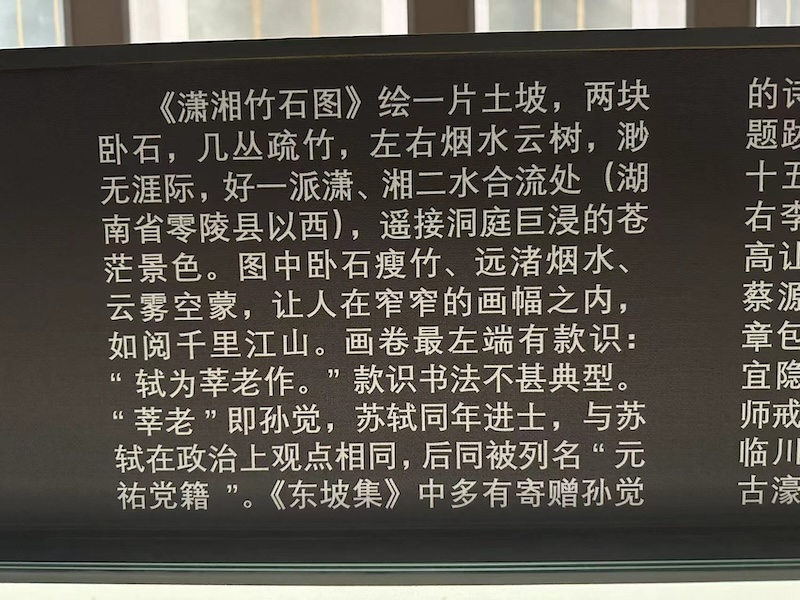

In the second phase of Nanjing Museum's "Endless Collection - Su Shi's Artistic Spirit of Calligraphy and Painting", the only work of Su Shi, "Bamboo and Stone Pictures of Xiaoxiang" (collected by the National Art Museum of China), is in the display cabinet. The black display board on it is an explanation of the work.

The "hundreds of thousands words" annotation always reminds me that this is the "Su Shi Exhibition"

Before seeing the exhibition, I had heard about the controversy over the "hundreds of thousands words of annotations". The curatorial team worked hard to supplement each work with short-length annotations. However, many viewers thought it was too lengthy and subjective, and it was difficult to understand the style and taste of the work. There is not much ink on the inscription, postscript and seal.

Judging from on-site experience, "annotations" indeed assist in the interpretation of works, but does Chinese painting need to be interpreted in this way?

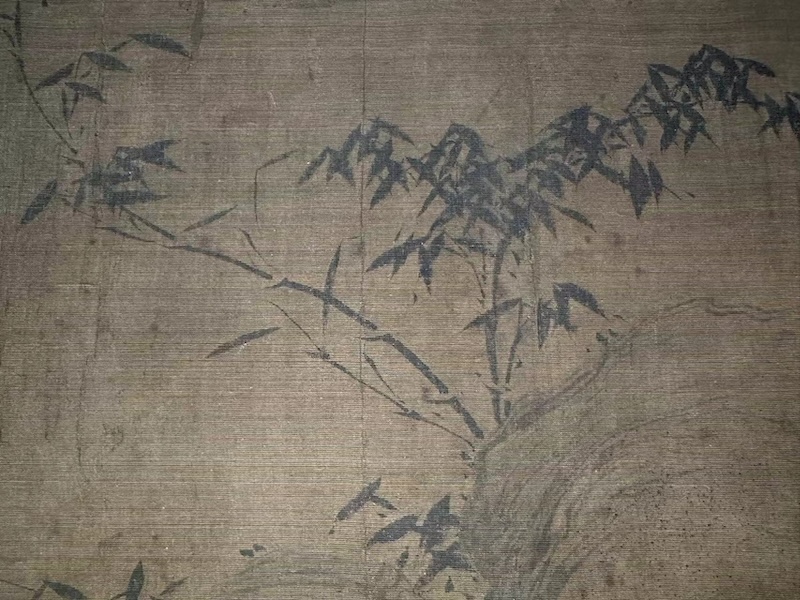

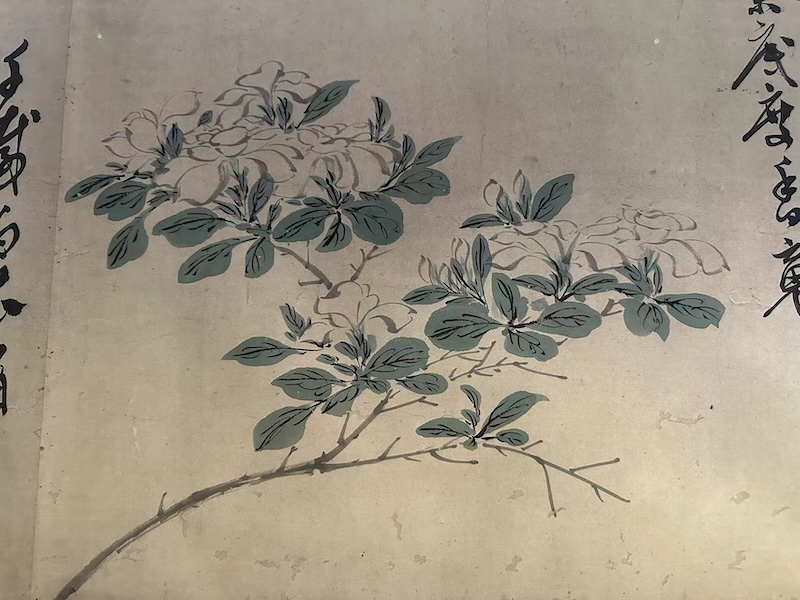

For example, when looking at the second issue of the only "Bamboo and Stone Pictures of Xiaoxiang" (inscribed by Su Shi) in the collection of the National Art Museum of China, this painting was donated to the National Art Museum of China by Deng Tuo. There is actually a big controversy as to whether it is authentic. Although I have seen the image many times on the screen and in books, the dynamic fluttering of the bamboo leaves in the painting and the subtle changes in the use of ink in the background clouds and mist are certainly not comparable to printed images.

"Bamboo and Stone Pictures of Xiaoxiang" (Collected by National Art Museum of China) Bamboo and Stone Parts

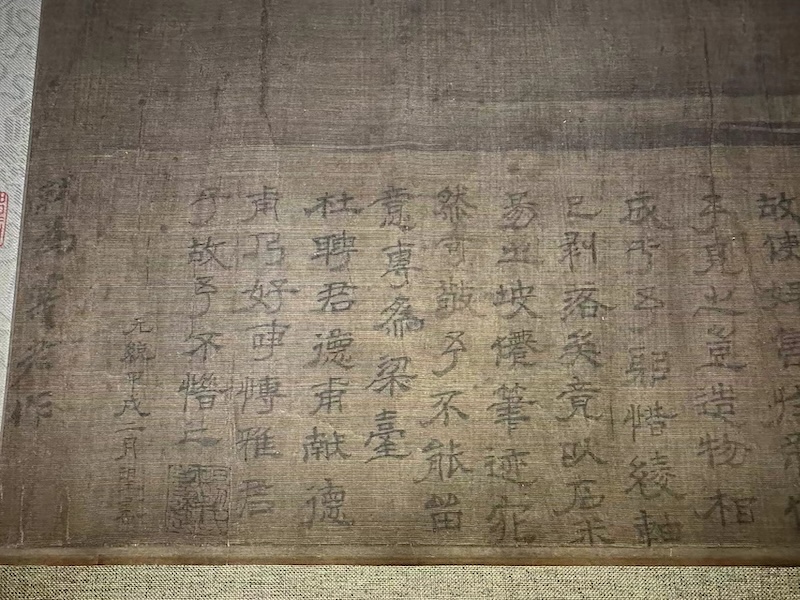

In the interpretation of the composition, which is as long as a composition, the prompt "Shi was created by Xin Lao" on the far left of the scroll is necessary. After reading this sentence, many viewers turned back to the front to look for the inscription; they also said, "The calligraphy of the inscription is not very typical." I don't know what it means. Isn’t it “not typical of Su Shi’s calligraphy style”?

The words are unclear, leaving people guessing. In fact, it would be better to point out the real and fake points of this work, which would be concise and clear.

The leftmost part of "Xiaoxiang Bamboo and Stone Pictures" is "composed by Shi Wei Xin Lao".

The exhibition's interpretation of the text of "Xiaoxiang Bamboo and Stone Pictures" found that the description of "like reading thousands of miles of mountains and rivers" is too subjective.

The exhibition uses this single work to lead three chapters about painting.

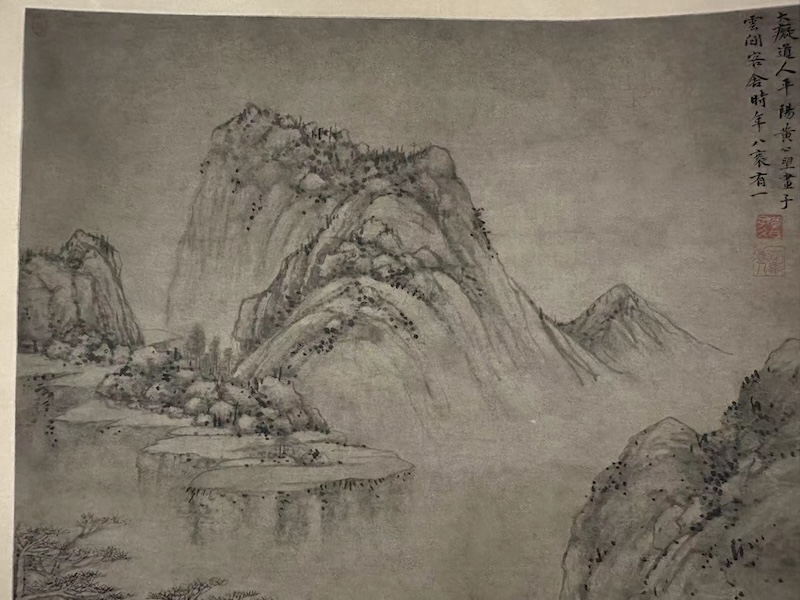

The first section "To express one's heart and what one wishes" comes from Su Shi's "Books, Zhuxiangs and Paintings First" " If you can write without asking for performance, if you are good at painting without asking for sales, you can write to reach my heart and paint to suit my will. " In this regard, the author My understanding is that Su Shi first proposed "literati painting" and believed that literati painted to express their temperament. This theory was practiced by scholar-official painters represented by Zhao Mengfu in the early Yuan Dynasty, which started the trend of Yuan Dynasty painting and calligraphy to incorporate the meaning of the brushwork into the painting and express the aspirations. Since then, the secluded landscapes of the "Four Yuan Schools" have become the model style of literati landscape painting. This has been formed. Then Dong Qichang traced it back to Wang Wei of the Tang Dynasty and discussed it as the "Southern Sect".

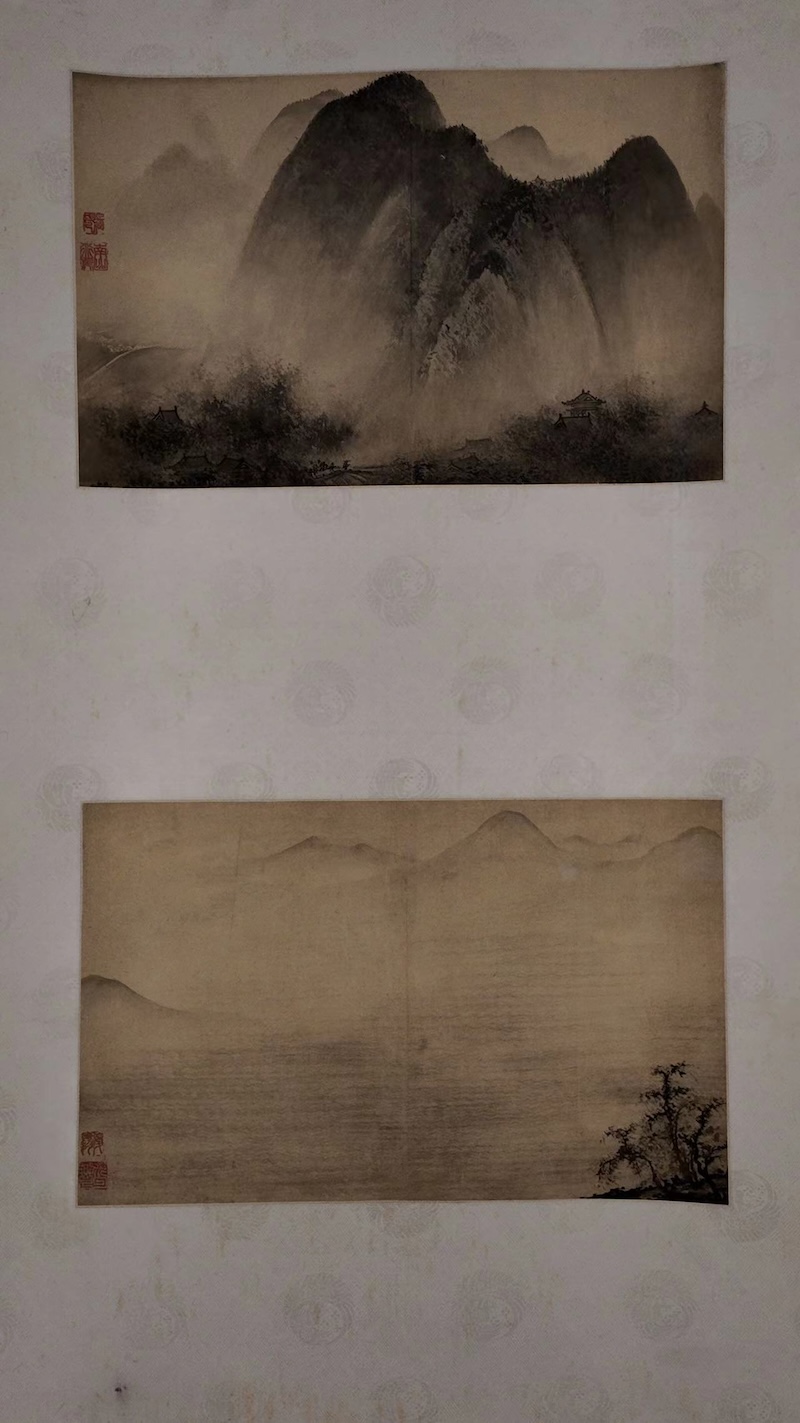

Huang Gongwang's "Quiet Picture of Water Pavilion" (detail), collected by Nanjing Museum

Huang Gongwang's "Fuchun Daling Picture", collected by Nanjing Museum

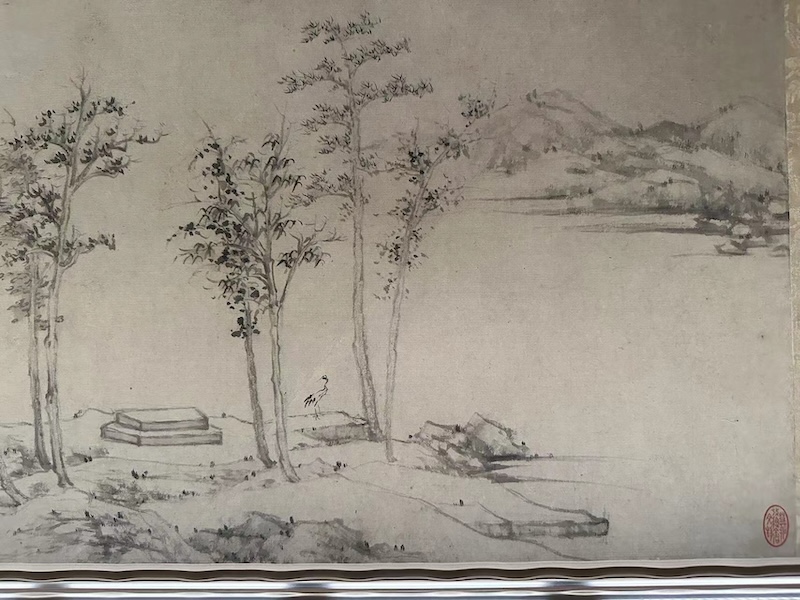

In the exhibition at Nanbo, the "Four Yuan Masters" besides Wang Meng were brought together, including Huang Gongwang's "Fuchun Daling Tu", "Shuige Qingyou Tu" and Ni Zan's "Helin Tu" (collected by the National Art Museum of China) ), the bamboo in Ni Zan's "Helin Picture" reminds people of what he wrote in "Zhang Yizhong's Painting of Bamboo": " The remaining bamboos are used to describe the breath in the chest and ears, how can we compare their similarities and differences, and the leaves?" The complexity and sparseness, the slanting and straightness of the branches! If you leave it on for a long time, others will regard hemp as reed, and you can't force it to be bamboo. It's really hard to understand. "Qi Er" echoes "Xiaoxiang Bamboo and Stone Pictures" and Su Shi's painting concepts, which is the finishing touch. But for some reason, the long text describing this painting finally focused on the "crane" in the painting, and related it to "There is a solitary crane coming across the river to the east" in Su Shi's "Fu on the Red Cliff", which is far-fetched.

Ni Zan, "Helin Picture" (detail), collected by the National Art Museum of China

Along the way, look at "Sitting in the Songzhai Picture" (Collected by the Nanjing Museum of the Anonymous Yuan Dynasty), "Evening Crossing on the Snow Stream" (Collected by the Anonymous Nanjing Museum of the Yuan Dynasty), to "Moon Walking in the Courtyard" by Wen Zhengming of the Ming Dynasty, and then to "Four Monks of the Qing Dynasty" , Wu Li, natural paintings are good paintings, but why should they be named Su Shi? This is more like a permanent exhibition of ancient calligraphy and painting.

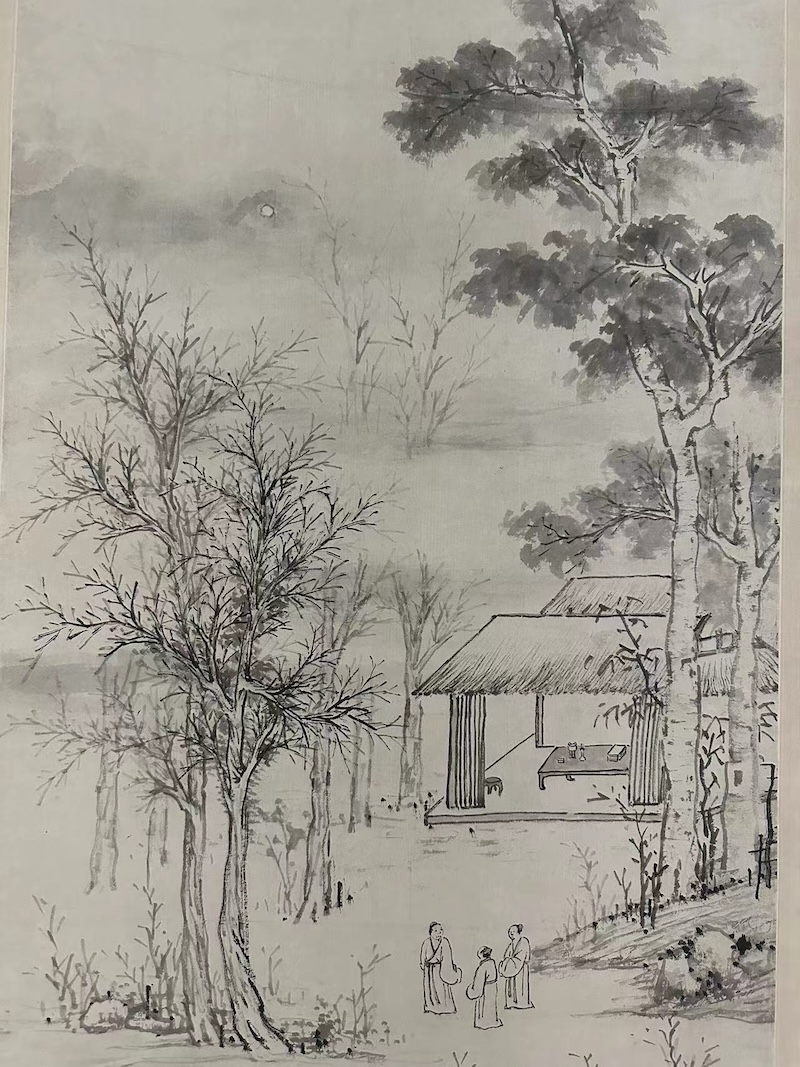

Wen Zhengming, "Moon Stepping in the Courtyard" (detail), collected by Nanjing Museum

Looking at it again at this time, most of the "hundreds of thousands of words" exhibition text emphasized by the museum is explaining the reasons for "titled Su Shi", and some of them are relatively suitable. For example, "Moon Stepping in the Atrium" is " Wen Zhengming's version of Su Shi's "Night Tour of Chengtian Temple", but more of it is self-justification. For example, Chen Rong's "Cloud Dragon Picture" is attributed to "Taking Heart and Comfort" through extensive quotations. Perhaps without the repeated reminders and annotations of these words, except for "Xiaoxiang Bamboo and Stone Pictures", this exhibition has little to do with Su Shi.

Whether it is "expressing the heart's contentment" or "writing about the relaxation of the chest", these are the essence of literati paintings. At the same time, they also pay attention to the viewer's self-perception, but the "hundreds of thousands of words" text limits the audience.

exhibition site

There is no distinction between "writing form" and "writing spirit", only a pile of works

The "Shape Writing and Spiritual Expression" section comes from the first one of Su Shi's "Two Broken Branches Painted by the Master of Yanling King": " When talking about paintings, they are similar in shape, and they are seen next to children. This poem must be written when writing poems, and it must not be a known poet. Poems and paintings are all the same. Heavenly craftsmanship and freshness. Zhao Changhua's sketches are so vivid and sparse, yet full of essence.

Exhibition scene, above is "Portraits of Ming Dynasties" (collected by the Anonymous Nanjing Museum).

Unexhibited portrait of Xu Wei

Judging from the context, Su Shi paid more attention to conveying the spirit, and earlier Gu Kaizhi's "writing the spirit with form" clarified the relationship between "writing form" and "writing spirit". The author believes that "writing form to convey the spirit" does not conflict with Su Shi's original intention. Perhaps to highlight this point, the curatorial team, after explaining the relationship between the two in words, displayed a set of photo-like "Portraits of Ming Dynasties" to emphasize what "writing the spirit with form" is. A closer look also has another meaning, but Together with other works of figures exhibited in this section [such as the "Horse Feeding Picture" by an unknown person from the Yuan Dynasty (with some Zhao Yong style) (collected by the National Art Museum of China), Chen Hongshou's "Miscellaneous Painting Album", Zeng Jing's "Portrait of Wang Shimin", etc.] Not in the same context. On the contrary, the flowers of Xu Wei and Chen Chun are closer to the meaning of "Zhao Changhua conveys the spirit" mentioned by Su Shi. In the album "Portraits of Ming Dynasties", there should be "Portrait of Xu Wei". If viewed together with Xu Wei's miscellaneous flowers, it will form a dialogue. , I don’t know why the “Xu Wei” page in this set of albums is not on display.

Chen Chun, "Viewing Objects and Flowers in Four Seasons" (detail), collected by Wuxi Museum

However, some of the landscape paintings of the late Ming and early Qing dynasties on display in this section are contrary to the commonly understood concept of "writing the spirit". Appreciating the precision of the brushwork and the inheritance of Nanzong is enough to apply the concept of "writing the spirit". It's really far-fetched. In addition, the depiction of goshawks and sparrows in "Goshawk Chasing Rabbit" by Zhang Lu (Ming Dynasty) is quite conceptual, blurring "depicting form" and "describing spirit".

Similar to the first section, the latter sections are displays of permanent exhibitions of calligraphy and painting after the Song Dynasty. If you ignore Su Shi or "write the gods" and just look at the works, there is still plenty to see. For example, rarely seen Nanbo collections such as "Herding Cows in Four Seasons" by Yan Ciping (Southern Song Dynasty) and "Landscape" by Zhang Fuyang (Ming Dynasty) are breathtaking and make people look at them again and again.

Yan Ciping, "Herding Cows in Four Seasons" (part of spring scene), collected by Nanjing Museum

Zhang Fuyang, "Landscape", collected by Nanjing Museum

Before the exhibition was over, a question lingered for a long time. Wouldn't it be more pure if we didn't use the name "Su Shi's artistic spirit of calligraphy and painting" and just looked at the works themselves?

Great view, but chaotic

Looking back at the exhibitions in the name of Su Shi in recent years, the 2020 "Romantic Figures of the Ages - Special Exhibition of Su Shi's Theme Calligraphy and Paintings from the Palace Museum Collection", which is mainly from the Palace Museum's own collection, features 78 pieces (sets) of calligraphy and painting, inscriptions, utensils, rare ancient books, etc. ) cultural relics, outlining a three-dimensional image of Su Shi. Su Shi's works on display include the collection of "New Year's Exhibition Celebration Posts and Calligraphy Posts", "Zhiping Posts", "Wang Shen Poems in Running Script", "Spring Posts" and "Returning to the Courtyard". The exhibition starts from Su Shi's circle of friends and those he worked with. Speaking of the era we live in, we first display the works of Su Shi and his mentors, including Su Shi's "Page of Poems in Running Script Inscribed on Wang Shen" and Wang Shen's "Picture of Light Snow in a Fishing Village". Each section of the exhibition closely revolves around Su Shi, which can be said to be a benchmark for Su Shi exhibitions.

In 2022, the "Mountains Looking Back to the East Slope - Special Exhibition of Su Shi's Theme Cultural Relics" and "The Eternal Romance of the East Slope - Su Shi's Theme Cultural Relics Exhibition" will be held in Su Shi's hometown of Sichuan and the place of exile in Hainan, focusing on history. Nature of land.

Among them, the Sichuan Museum exhibits the "Xiaoxiang Bamboo and Stone Pictures", "Dongting Spring Ode: Zhongshan Pine Mash Ode Volume" and "Yangxian Tie"; the Hainan Museum exhibits the "New Year's Exhibition Celebration Posts, People Come to Get Calligraphy and Calligraphy Volume". In contrast, this Nanjing Expo has no advantage in terms of Su Shi’s works on display or its relevance to Su Shi. The number of more than 150 works on display is twice that of the Forbidden City exhibition, but it is grand but chaotic. For example, Ren Bonian's "Dongjin Farewell Picture", borrowed from the National Art Museum of China, has a comic-like style of painting, which makes it appear dramatic.

Although the grand exhibition of calligraphy and painting cultural relics is limited to a three-year dormancy period, and Nanbo does not have a collection of Su Shi's works, why should Su Shi be the theme? Finding another entry point and streamlining the exhibits can be a way to gather more energy.

Lushun Museum collects Su Shi's "Yangxian Tie" (the original will be on display from June 16 to July 16)

In fact, not far from Nanjing, the "'Almost the Frontier' Special Exhibition of Su Dongpo's Authentic "Yangxian Tie"" is on display at the Yixing Museum. Even on weekends, the exhibition does not require reservations and has few visitors. Although there is only one Su Shi work on loan from the Lushun Museum, "Yangxian Tie" (the original is on display from June 16 to July 16), the museum focuses on the history of Su Dongpo's land purchase in Yixing and draws on Su Shi's work from the urban context. The connection is cut through, supplemented by the exhibition of cultural relics in the museum, which is simple, unique and impressive.

In the special exhibition of "Almost the Forerunner" of Su Dongpo's original "Yangxian Tie" at the Yixing Museum, an audience is quietly admiring the "Yangxian Tie".

This exhibition at Nanjing Expo seems to be drawing on Dong Qichang's exhibition at Shanghai Expo many years ago, trying to connect the history of Chinese calligraphy and painting in one person. However, there is a huge gap in the curatorial skills and exhibition presentation between the two.

Dong Qichang in the late Ming Dynasty was a key figure in the turning period in the history of Chinese literati calligraphy and painting. His "Northern and Southern Sects" can be traced back to the Jin and Tang Dynasties, and their influence continues to this day. His collection includes Wang Xizhi, Yan Zhenqing, Huai Su, and of course Su Dongpo. When these works that influenced Dong Qichang are gathered in the Shanghai Expo exhibition hall, they not only tell how Dong Qichang's calligraphy and painting were shaped, but also present the spirit of Chinese art. Nanbo only used Su Shi as a starting point, trying to sort out Su Shi's influence on later generations of calligraphy and painting, but it seemed that it only applied the works at hand that could be exhibited to Su Zi's calligraphy and painting theory, and the final presentation was inevitably ambiguous and contradictory, or implicitly said "Integration with each other is not a matter of distinction."

Exhibition site, Shen Zhou's "Poetry of Falling Flowers" from Nanbo Collection

The above are some of the author’s experiences of Nanbo’s “Endless Collection—The Artistic Spirit of Su Shi’s Calligraphy and Painting”. They are just superficial views. After all, the exhibition was prepared for three years and I only watched it for three hours. I may not have understood the intentions of the curatorial team.

However, the following points should be pointed out by viewers who do not understand Su Shi or even Chinese painting:

1. The exhibition design is too old and dull. There is no design at all in the preface, conclusion, or a large number of explanatory texts for the works.

For example, the origin and conclusion of the exhibition title "Endless Possession" seem to be directly collaged and output on an exhibition wall. In addition, most Chinese paintings and calligraphy works are on a white background. Generally, when they are exhibited, the wall colors are emphasized to highlight the works. However, in this exhibition, the wall colors are lighter.

At the exhibition site, the display boards are piled with content and lack a sense of design.

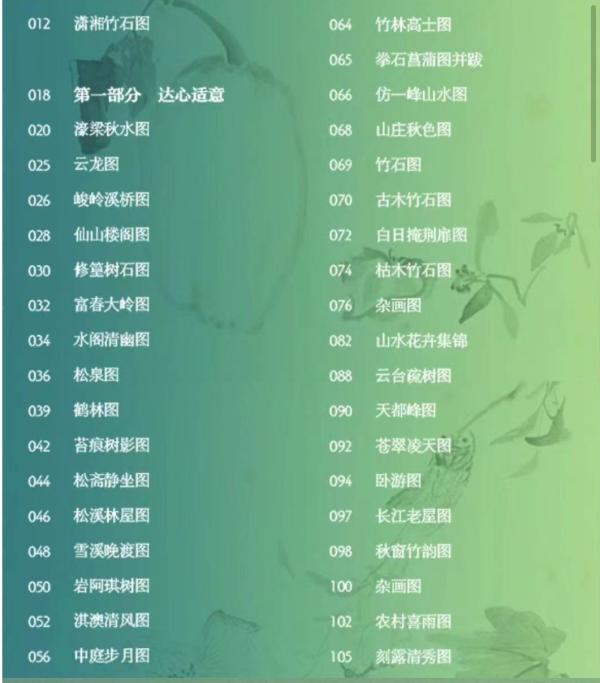

2. The published list of exhibits only contains the names of the works and no author dynasty, which is quite amateurish.

The list of exhibits in the "Expressing the Heart and Feelings" section of the exhibition only has the names of the works, and the author of the dynasty is unknown.

3. What is puzzling is that the author found debris on Chen Hongshou’s works displayed in the closed showcase. In addition, some viewers reported that the joints of some showcase glass cabinets were not filled with glass glue, and hard paper could be inserted. If any viewers accidentally dripped beverage liquid, it may cause damage to calligraphy and painting cultural relics.

Among Chen Hongshou’s works in the display case, there are silica gel-like debris on the lower left side of the child.