Japanese art has a complex relationship with "perfection," yet the cultural concept of "wabi-sabi" embraces the beauty of imperfection.

The new exhibition of Japanese art recently unveiled at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is titled "The Three Perfections," showcasing the millennia-long heritage of Japanese artistry. Rooted in the literati traditions of China, "The Three Perfections" refers to poetry, calligraphy, and painting, and the exhibition focuses on artworks that elegantly combine these three distinct expressive forms.

Unfortunately, the art form known as "Southern painting," which once flourished and was highly esteemed in Japan, is now in decline.

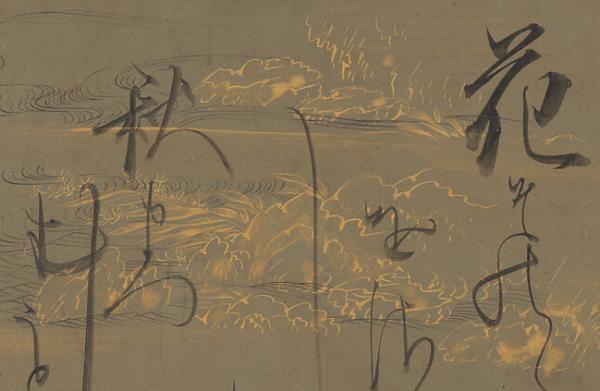

Watanabe Shikō, "The Cold Mountain and the Pickers" (Detail), Early 1770s

"The Three Perfections: Japanese Poetry, Calligraphy, and Painting from the Collections of Mary and Cheney Cowles," continues the tradition of showcasing Japanese art at The Metropolitan Museum. In 2015, the museum held the highly acclaimed "Discovering Japanese Art," featuring over 200 masterpieces across various art forms, detailing how the museum built a premier collection of Japanese art over more than a century. The 2017 exhibition "Japanese Bamboo Art" was also notable, portraying bamboo artistry through a selection of complementary artworks, including kimonos, netsuke (miniature sculptures), and hanging scrolls.

In this exhibition, The Met once again surrounds its thematic art with an array of rich Japanese crafts, aiming to immerse visitors in the atmosphere of Japanese culture and aesthetics while engaging their senses as much as possible. "When you create calligraphy, you smell the ink, you touch the brush, and you have exquisite lacquer boxes. There are many such connections in this exhibition, bringing together a variety of sensory experiences," said exhibition curators John T. Carpenter and Monika Bincsik.

Ono no Tōfu, "Illustrated Tale of Genji" (Detail)

The concept of "poetry, calligraphy, and painting" as the "Three Perfections" originates from China. In ancient China, scholars used these art forms for self-expression. Painting was seen as "silent poetry," while poetry was viewed as "speaking pictures." Scholars were trained in calligraphy from a young age, integrating their brushwork into painting.

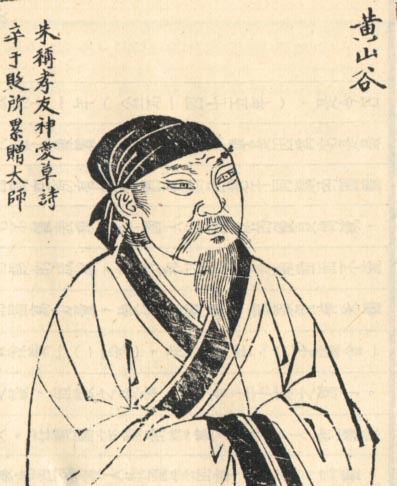

According to British art historian and sinologist Michael Sullivan (1916-2013) in his 1974 work "The Three Perfections: Chinese Painting, Poetry, and Calligraphy," the term "Three Perfections" originated with the Tang dynasty poet, painter, and calligrapher Zheng Qian (691-759), who was so admired by Emperor Xuanzong that the emperor inscribed the words “Zheng Qian’s Three Perfections” after his painting "The Cangzhou Map."

Calligraphy has always been regarded as the highest art form in China, its artistry and expressiveness existing independently of the meanings of the words. Regarding calligraphy as a means of self-expression that reveals the writer's character, Han dynasty Confucian scholar Yang Xiong (53 BC – 18 AD) wrote: "Words are the voice of the heart. Calligraphy is the painting of the heart. Voices and pictures, gentlemen and petty people see it!"

However, it was not until the Northern Song dynasty that painting truly equated to poetry and calligraphy. Su Shi remarked on the Tang painter Wang Wei, saying: "Taste the poetry of Mo Jie, there is painting in the poetry; observe the painting of Mo Jie, there is poetry in the painting." A similar sentiment was echoed by Su Shi's friend Huang Tingjian regarding Li Gonglin’s work: "Li Hou has lines he does not want to speak, light ink reveals a silent poem," highlighting the connections between art forms at that time.

Uramatsu, "The Orchid Pavilion Gathering," 1829

This exhibition follows the clue of "poetry, calligraphy, and painting" in the context of Chinese character culture, showcasing rare Japanese painting and calligraphy donated (or soon to be donated) by the Cowles couple (Mary and Cheney Cowles). These works span nearly a millennium, displaying the power and complexity of calligraphy, as well as its creative integration with pictorial art.

The ten exhibition halls each create a different atmosphere, inviting visitors into various historical periods while exploring Japanese aesthetics. For instance, one gallery was filled with the sound of poetry recitations from the 11th century, creating an enchanting (and hypnotic) ambiance. "The sound is very melodious and tranquil," Carpenter noted. "When poetry is recited, it alters its rhythm and meaning, just as it is engraved in a work through calligraphy."

Another hall allowed visitors to witness a poetry gathering, attempting to transport them back to that era of elegant assemblies. There was also a space displaying lacquerware crafted by monks, originally used for worship, which many believers would touch in Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples for blessings. "You can see the traces left by people touching them over the years," Bincsik remarked.

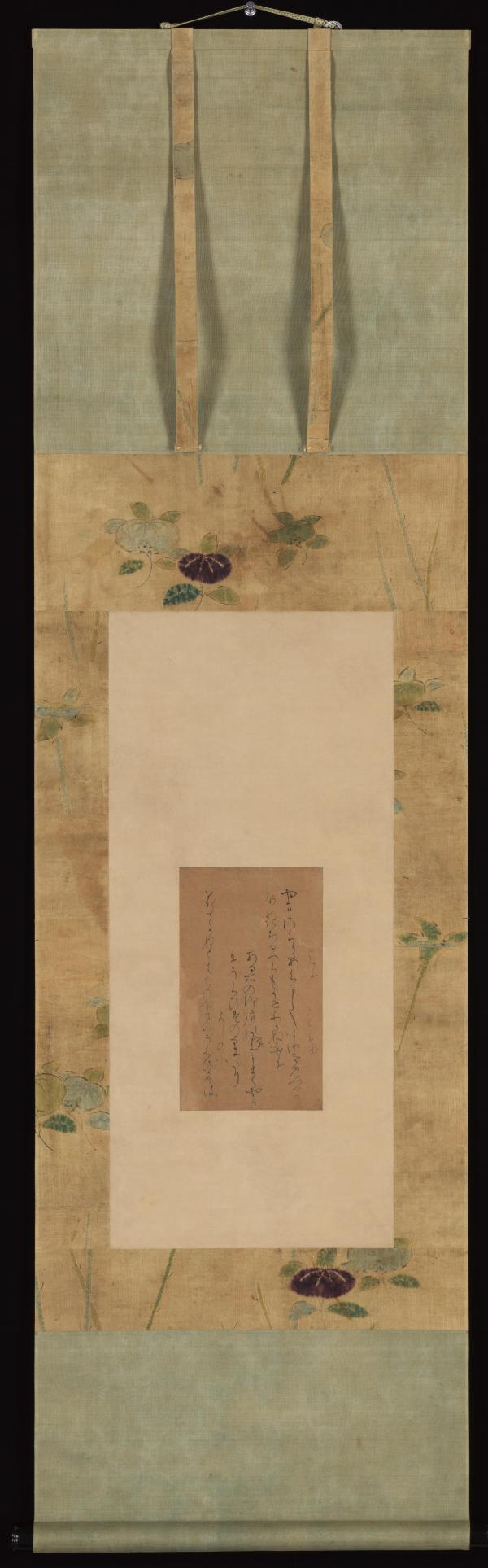

The classic Japanese literary work "The Tale of Genji" served as inspiration for many of the artworks in the exhibition. Despite its author, Murasaki Shikibu, being a woman, the calligraphy tradition that emerged from the text remained male-dominated.

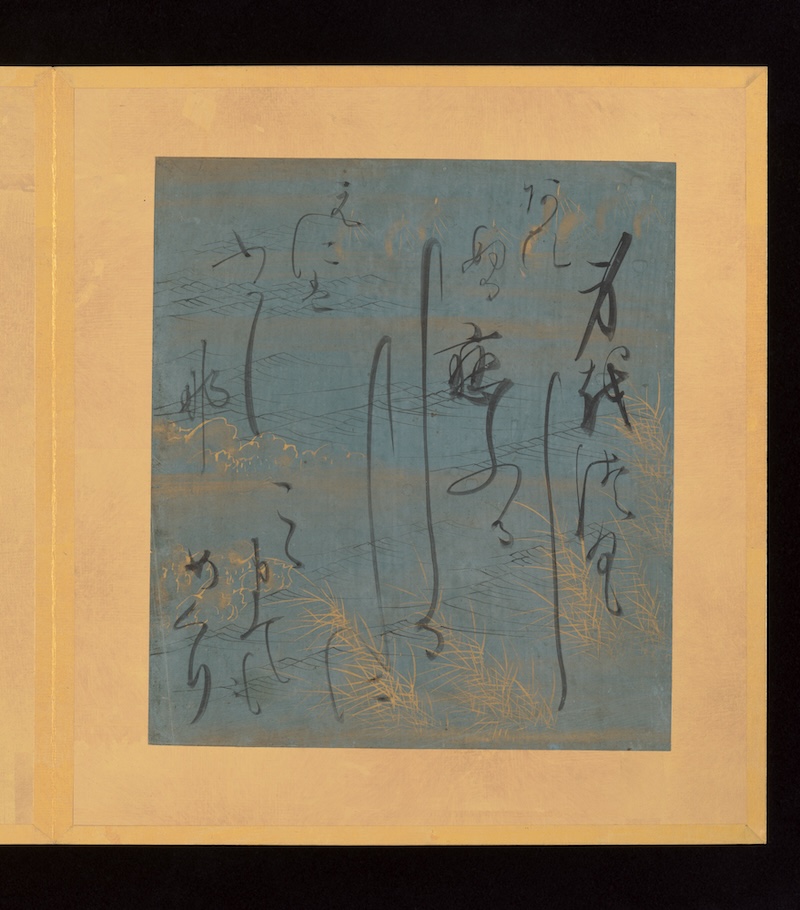

Tosa School, Ono no Tōfu, "Illustrated Tale of Genji," Early 17th Century (One Page)

The exhibition attempts to uncover female creations, featuring Ono no Tōfu (1559/68-1631), one of the most celebrated artists from the Azuchi-Momoyama to early Edo periods, who excelled in poetry, calligraphy, painting, and music. Ono no Tōfu transformed classic poetry into calligraphy, adorning the pages of the "Tale of Genji" created by Tosa school painters (attributed to Tosa Mitsuyoshi) with her exaggerated vertical strokes, representing one of the finest examples of women’s calligraphy in the Momoyama period (1573-1615). "I think she is even more outstanding than the three famous male calligraphers of her time," Carpenter stated.

Tosa School, Ono no Tōfu, "Illustrated Tale of Genji," Early 17th Century

Tosa School, Ono no Tōfu, "Illustrated Tale of Genji," Early 17th Century

During the earlier Heian period (794-1185), women played a crucial role in the development of the unique Japanese writing system, kana, which came to be known as "onna-de" or "woman's hand." This era's female calligraphy is exemplified in the late 11th-century manuscript of the "Collection of Beautiful Flowers," where the fluid elegance of women's calligraphy is displayed, showcasing how calligraphers broke the lines when transcribing popular poetry to create a dynamic composition.

(Attributed to) Shōtō no Shō (Tachiwaka), "Collection of Beautiful Flowers," Late 11th Century.

Transcription: "I wonder if the wild cherry blossoms are just for their color. In a world where flowers fall without the wind blowing."

The mid-17th-century "Picture of a Courtesan Reading" features an inscription from the courtesan Moshimo of the Shimabara district in Kyoto, with lines adapted from the poet, scholar, and calligrapher Fujiwara no Teika (1162–1241): "Who in this world, reveals color, pen and ink delight, revealing profound meaning." The young woman depicted in the painting reads by the light, her hairstyle a refined version of the "Gosho style."

Anonymous, "Picture of a Courtesan Reading," circa 1655–1661

In traditional Japanese culture, both Zen Buddhism and the tea ceremony have been significantly influenced by calligraphy. The curators of this exhibition have meticulously arranged exquisite artworks that evoke the ambiance of the tea ceremony, showcasing a facet of Japanese tea culture. Carpenter noted, "Calligraphic works displayed during a tea gathering are vital to setting the atmosphere; some believe the most important item in the tea ceremony is the hanging scroll of calligraphy."

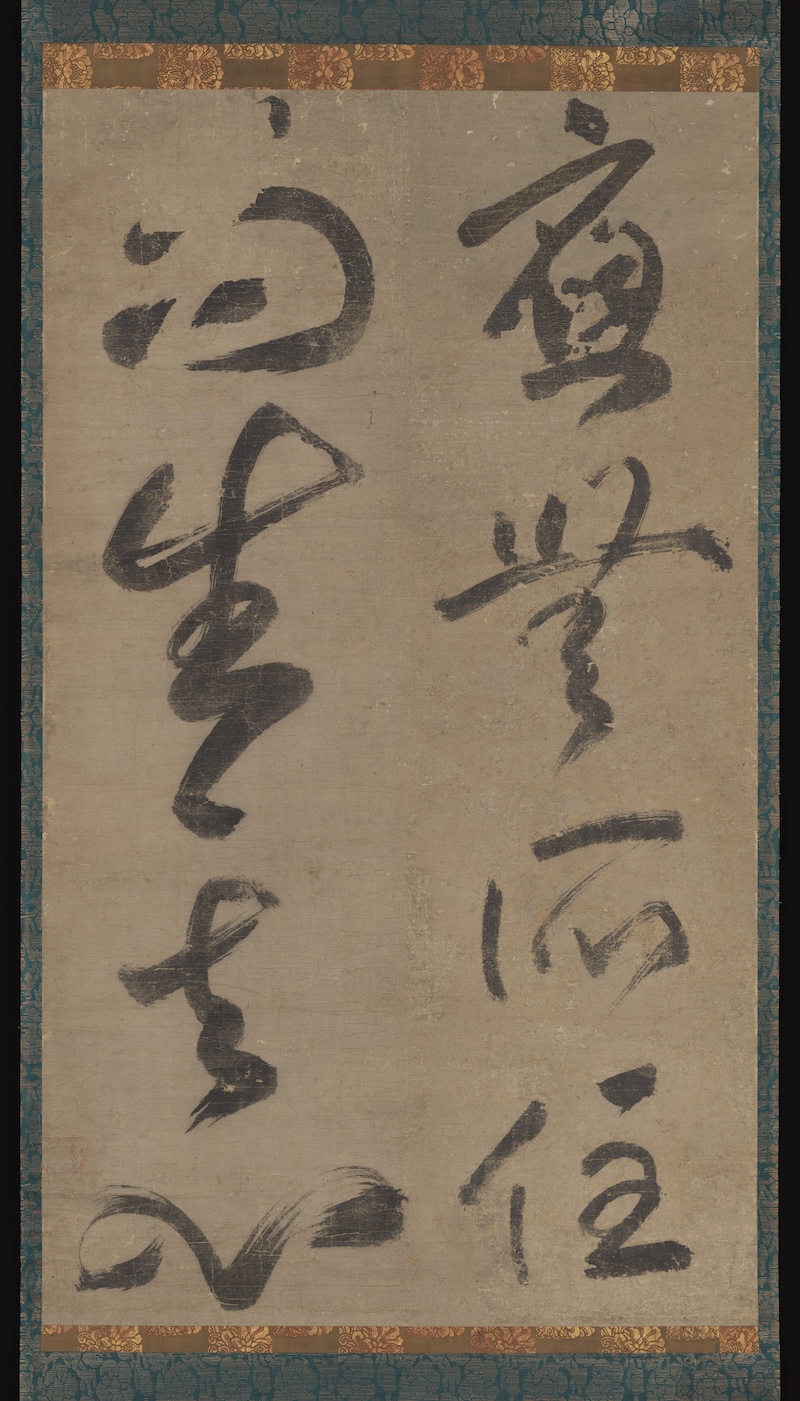

Zen monk Muko Soji (1275-1351) and tea seller Jōshō (real name Shibayama Motoaki, 1675-1763) created bold and vigorous calligraphies. These works were entirely inscribed with kanji, embodying the Zen ideal of transcendence for spiritual enlightenment, wherein the dynamic strokes manifest urgency, spontaneity, and freedom.

Muko Soji was a prominent figure in early Zen history in Japan, active during the late Kamakura to early Muromachi periods. Unlike many predecessors, he did not travel to China but was taught by the exiled Zen master Ichian and several Japanese monks who had traveled to China. Soji primarily operated in Kamakura until 1333 when he was invited by the emperor to relocate to Kyoto, where he spent the remainder of his life. "One should be without a dwelling and allow one's heart to be born" conveys a fundamental Zen principle — awakening can be achieved by transcending material and the present world.

Muko Soji, "One Should be Without Dwelling and Allow One's Heart to be Born," Early 14th Century

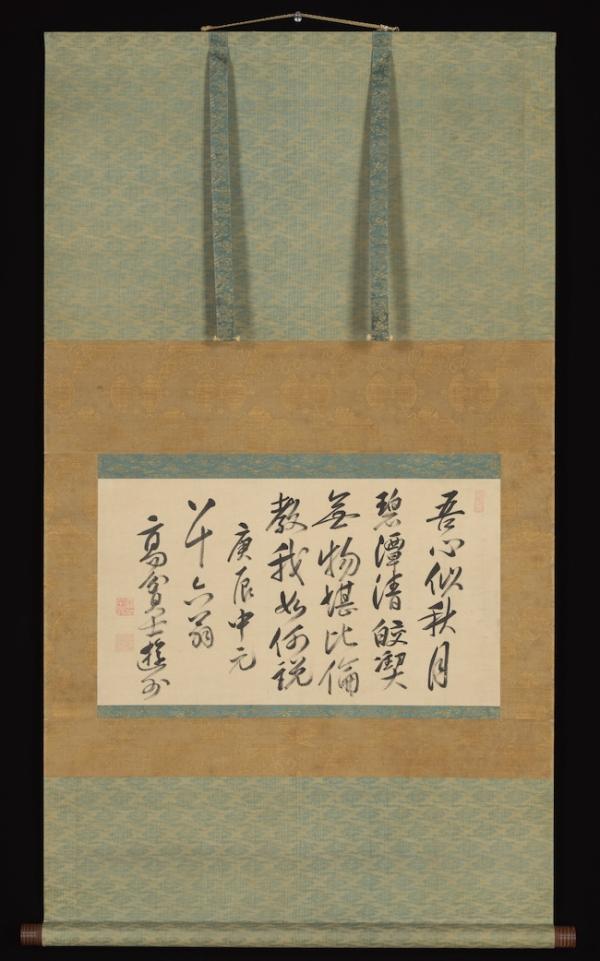

Jōshō, a Ōbaku Zen monk, played a key role in promoting Chinese tea brewing. He inherited the tradition of Chinese calligraphy and developed a bold, vibrant, and fluid style. Here, he inscribed a famous poem by the Tang dynasty poet and monk Hanshan: "My heart is like the autumn moon, clear and bright over the pond. Nothing can compare to its elegance; teach me how to express it."

Jōshō, "Hanshan's Five-Character Quatrain 'Autumn Moon,'" 1760

Hanshan's imagery often appears in Japanese paintings. The mid-Edo period haiku poet and painter Watanabe Shikō (1716–1783) depicted the two eccentric Zen figures from the eighth century in a pair of hanging scrolls: on the right is Hanshan, holding a scroll of poetry. The other figure, Shide, stands with his back to the viewer, concealed by a large bamboo hat, with a broom in hand, which reminds us of his role as a temple janitor. Hanshan and Shide symbolize the nonconformist pursuits of Zen Buddhism and frequently become subjects in paintings and poetry.

Watanabe Shikō, "The Cold Mountain and the Pickers," Early 1770s

In this artwork, Watanabe Shikō utilized bold brushstrokes, employing a large brush to outline the robes, demonstrating his brilliant skill in calligraphic strokes. For the hair, Shikō used a dry brush over wet ink, creating a disheveled texture that captures the free-spirited nature of the hermits.

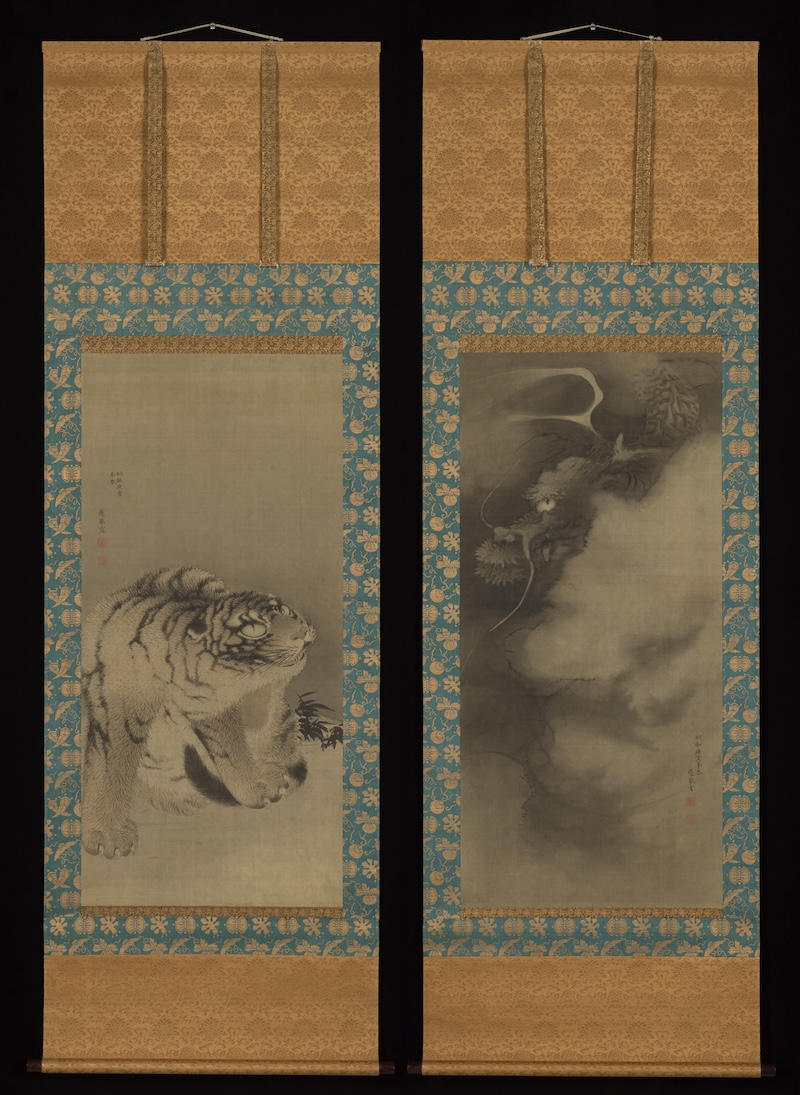

Rimpa School, "The Dragon and the Tiger," 1770

The dragon and tiger,