This year marks the tenth anniversary of the successful application for UNESCO World Heritage status for the Silk Road. With the support of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Cultural Heritage Bureau, The Paper's “Cultural China Journey: Tianshan Silk Road” column has been visiting cultural sites along the Tianshan Mountains in Xinjiang, seeking out the scattered traces of cultural arts along the Silk Road, bearing witness to the grandeur and vastness of the Western Regions. In addition to a series of videos, starting today, we will be publishing notes, sketches, and photographs from this journey, collectively titled “Ink and Brush of the Tianshan Silk Road.”

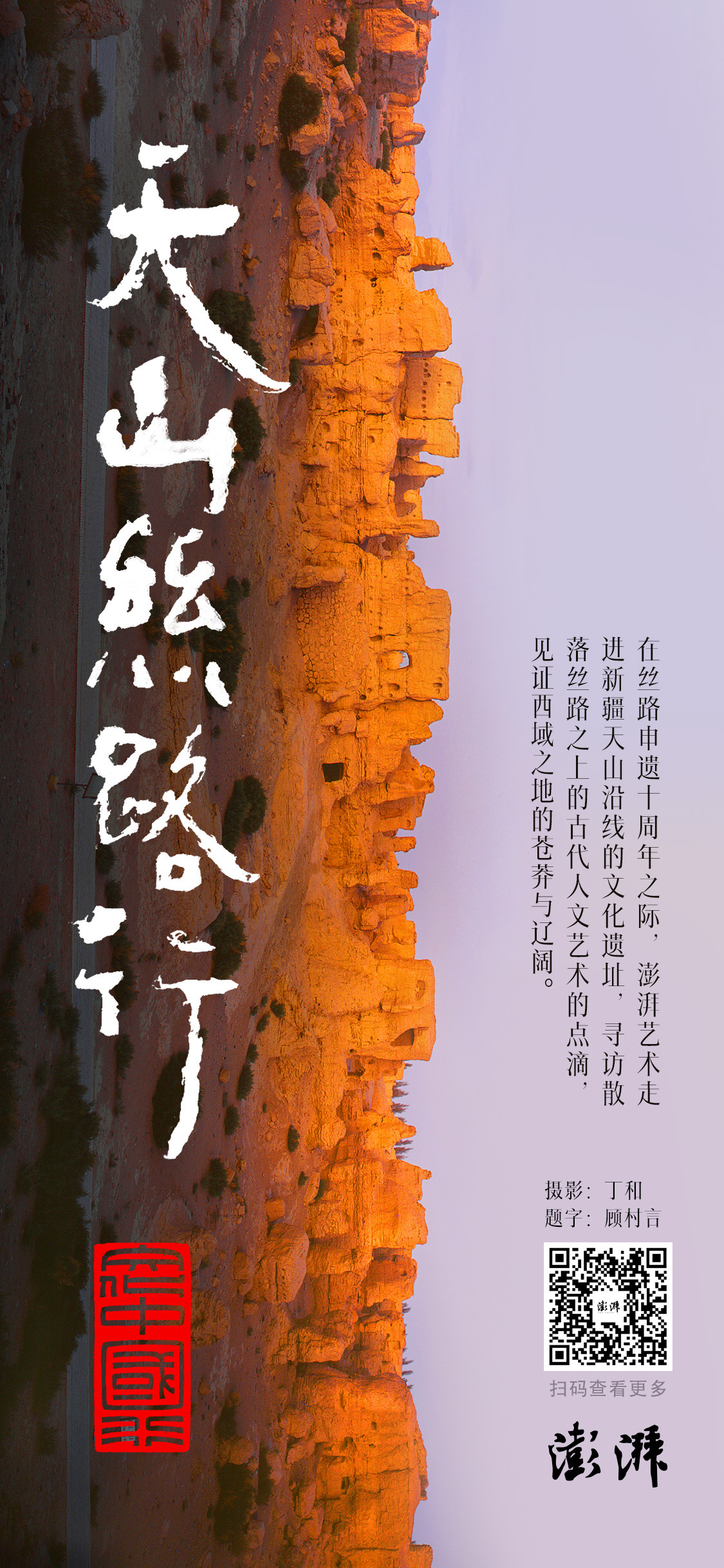

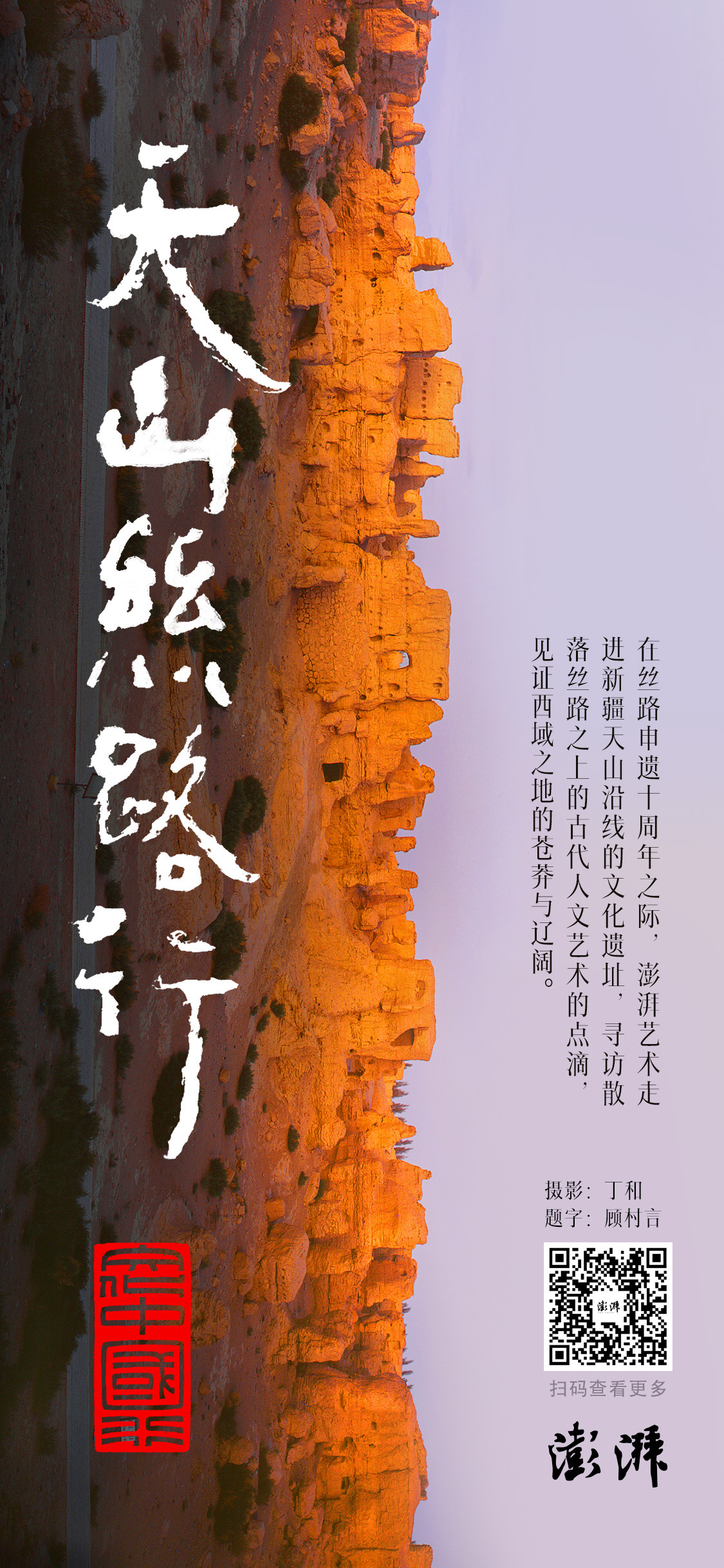

Poster for “Cultural China Journey: Tianshan Silk Road” (scan the QR code to access the special feature), Photography: Ding He Calligraphy: Gu Cunyan

The Winds of Daban City

Driving from Urumqi towards Turpan, Bogda Peak has always been shadowing us, occasionally hidden, occasionally visible, with its unique and majestic silhouette.

In reality, Bogda Peak is quite far away; what’s closer are the intermittent stretches of barren land and the long, remote Gobi desert.

And then, there’s the immense wind.

It’s astonishing to see so many wind turbines, especially near the important Silk Road town Daban City. In the desert, thousands of wind turbines stand tall, densely clustered like gigantic fans, spinning in the breeze. The sight is as formidable as an army, set against the high, snow-capped mountains, blue sky, and white clouds. The stunning beauty of nature combined with human ingenuity is deeply moving.

Wind turbines near Daban City

The howling wind became louder as the Jeep seemed to sway slightly; Liu Huanying, a photographer from Xinjiang in his sixties, firmly grasped the steering wheel, slowed down, and reassured us: “We’ve reached the thirty-mile windy area near Daban City. The winds are strong here, but it’s no big deal. When the wind really picks up, with flying sand and gravel, cars must pull over to a windy shelter. We absolutely cannot drive on.”

There indeed are designated windy shelters—essentially, larger parking areas with windbreaks and buildings.

It is said that when the wind is strong, elementary school students in Daban City will pack a few stones in their backpacks to add weight and prevent being swept away by the strong wind. A local saying goes: “Daban City, the old windy mouth, big winds and small winds every day; small winds bend the trees, big winds send the stones flying.”

Even more astonishing, over a decade ago, a train traveling from Urumqi to Aksu was overturned here by winds exceeding level 12, with sand and gravel swirling, literally blowing 11 carriages off the tracks...

I had never imagined that the winds of Daban City could be so fierce and alarming.

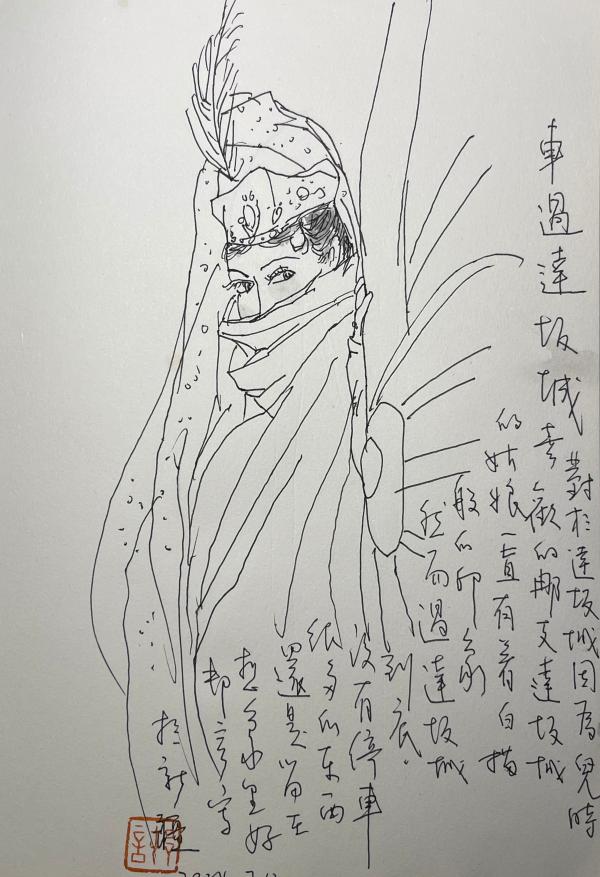

For me, Daban City has always been linked to the song "The Girl from Daban City," which I loved in my childhood. It has inexplicably formed a vivid image in my mind of a bright and cheerful little town: Uyghur girls with long braids and big eyes, hardworking yet humorous young men, cracking whips, sharp whistles, rattling carts, large and sweet watermelons, and unique wedding customs...

Pen sketch titled “Passing Through Daban City” Gu Cunyan Illustration

—But it’s all just imagination; the car didn’t stop.

Daban City was merely a fleeting glimpse by the highway, a place I passed through.

In the lyrics of "The Girl from Daban City," which were compiled by Wang Luobin, one line goes: “If you want to marry, don’t marry anyone else, be sure to marry me. Bring your dowry and your sister, and ride in that cart.”

Why should one bring their sister to get married? This childhood question remains unanswered to this day.

Flame Mountain

During the scorching summer, the highest temperature isn’t in the so-called “four furnaces” like Chongqing or Wuhan, but at Turpan’s Flame Mountain—where surface temperatures can peak at 82°C. If you place an egg there, it will surely be cooked.

Can one actually stay there?

The answer is a resounding yes!

In fact, a considerable number of tourists visit Flame Mountain, many of whom come to relieve dampness or acne. The sandy pits beside Flame Mountain are quite popular, where visitors sit or lie down, effectively driving out dampness and chill—almost a sensation of a mini social media star.

During summer, rain is rare in Turpan, but strangely, before setting off to Turpan, it began to pour, as if the Iron Fan Princess had specifically fanned us with her banana leaves. And right after arriving in Turpan, the rain stopped.

In the air, there was a refreshing feeling along with a hint of sweetness from grapes welcoming us. Local photographers Huang Bin and Cao Li joked, “This rain is too rare, as if it’s here just to wash away the dust for you.” The photographers were as excited as children, already imagining the translucent light and shadows in the ancient city of Jiaohe at dusk after the rain.

After the rain, as we passed Flame Mountain, we beheld that large red-brown mountain, as if re-ignited, utterly barren without a hint of greenery, wild folds stretching downward like flickering flames, probing into the earth’s layers.

The temperature would likely no longer be the merciless 82°C.

A brief peek out the car window reveals several camels lazily resting at the entrance to the scenic area, sound asleep.

“As soon as I arrive in Xinjiang, all ailments vanish”

Mr. Feng Qiyong at age 83, traveling in Xinjiang with his camera Photo by Ding He

“As soon as I arrive in Xinjiang, all ailments vanish.”

—These are the words of Mr. Feng Qiyong as conveyed by his wife, vividly expressed.

The elder's deep affection and intense thought for Xinjiang, coupled with his full focus during his explorations, are encapsulated in that single sentence.

Personally, I feel that “as soon as I arrive in Xinjiang, my chest opens up, and I am filled with energy.” In other words, going to Xinjiang is like recharging one's life, providing a chance to truly commune with the spirit of heaven and earth.

For someone like me, long-residing in the Jiangnan region, arriving in Xinjiang not only means a retreat from dampness but also brings a profound sense of vastness, grandeur, and spiritual freedom.

Everything feels expansive, even mundane tasks like buying fruits and vegetables are weighed by the kilogram, rather than the pound.

Ding He, a photographer deeply enchanted by the cultures of the Western Regions, engages as a researcher at the Kucha Research Institute. He asserts that when he arrives in Xinjiang, he feels an inexhaustible source of energy.

Seeing is believing; this is no empty talk.

A Shanghai local from the banks of the Huangpu River, influenced and guided by Mr. Feng Qiyong, has been dreaming of capturing the remnants of ancient Western culture through photography for decades. Letting his sentiments intertwine with this endeavor is truly resonant.

This visit marked Ding He's 46th entry into Xinjiang, carrying a backpack with heavy camera equipment, including the gigantic Ebony 8×10 film, traversing through the ancient sites in Xinjiang. A tall figure, he was soaked in sweat, yet full of spirit.

Ding He is one of the planners for the “Tianshan Silk Road Journey.” In fact, tracing back to the origin of this planning still involves Mr. Feng Qiyong’s words “as soon as I arrive in Xinjiang, all ailments vanish.”

Ding He loves to joke and has a natural affinity with the elderly; informally, he claims the title of “expert in soaking in Shanghai.” He has developed deep connections with great figures of his time, such as Feng Qiyong, Rao Zongyi, Ji Xianlin, and He Youzheng, receiving numerous inscriptions from these celebrities, along with their paintings—both big and small—as well as direct or indirect support for his photography exhibitions, all serving as clear evidence.

In the last years of his life, Mr. Feng Qiyong reflected on the origins of cultural exchanges between the East and the West, inspired by the research of Xuanzang and "The Great Tang Records on the Western Regions,” including writings by scholars like Klaproth, Jullien, and Berthold Laufer. His obsession with Western culture, the Silk Road, and Xuanzang’s pilgrimage led him to carry a camera to Xinjiang over a dozen times. He visited the Pamir Plateau three times, traversed the Taklamakan Desert twice, and circled the Tarim Basin to document and explore for his academic research. After years of vetting, he even confirmed the ancient path that Xuanzang took back home at an altitude of 4700 meters, establishing a monument to commemorate it.

If there weren't a true passion, how could one go to such lengths?

In 2005, Mr. Feng Qiyong (right) and Ding He (left) in Xinjiang’s Lob Nor

Ding He’s documentation of Xuanzang’s route came about because of Mr. Feng Qiyong’s recommendation and guidance. In 2005, he accompanied the 83-year-old Mr. Feng to Lob Nor for a research expedition on Xuanzang’s journey. Mr. Feng had noted in his lyrics for "Eight Sounds of Ganzu" that reads, “With good friends on perilous paths and treacherous peaks, traversing rugged cliffs, yet feels like riding a light horse. Ultimately, mountains and rivers are beautifully endowed, gathering coral into nets.”

Along the journey, if Mr. Feng Qiyong is mentioned, Ding He, who had just been joking around moments ago, would immediately become serious, brimming with respect. He shared that the Mr. Feng he knew was always equipped with a camera, reflecting a profound affection for the Western realms. “I still remember he carried two cameras and three lenses, fully equipped with both long and short guns. The cameras were never out of his grasp, always hanging in front of him. His right hand tightly held the body, as if alert and poised to capture any precious images that warranted recording. He loaded and unloaded his film himself. Come nightfall, while the young ones settled into deep slumber after a long day, Mr. Feng would still be at his desk, meticulously taking notes under the light.”

That person has departed, yet the ink still flows, and the light and shadow remain.

The journey continues.

A Melody of Sorrow is the Fire State

The itinerary in Turpan was too tight, so I didn’t manage to visit the ancient city of Gaochang, where Xuanzang once passed.

Yet, it feels less like a regret since I’ve been there before.

I recall that visit to the ancient city of Gaochang about seven or eight years ago, apparently around midday during the summer heat. Just stepping around, the sweat poured down; the immense historic site felt like a steamer, heat radiating everywhere with scarcely a soul in sight.

However, as I was leaving Gaochang, I unexpectedly encountered a Uyghur old man behind a weathered wall.

The old man wore a four-cornered cap, his face covered in deep wrinkles as if carved or chiseled; barefoot, he casually sat on a square mat, cradling a musical instrument—a three-stringed lute, perhaps a rawap—and in front of him sat a hard paper box with a sign in Chinese characters that read: “Ten yuan per session.”

I dropped a ten-yuan bill.

The old man glanced at it and nodded.

—In a fleeting moment, a desolate, distant melody with a hoarse voice emerged beside the