This year marks the tenth anniversary of the successful bid to inscribe the Silk Road as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. With the support of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region's Cultural Relics Bureau, the "Cultural China Journey: Tianshan Silk Road" column of The Paper has recently been visiting cultural sites along the Tianshan Mountains in Xinjiang, exploring the cultural and artistic fragments scattered along the Silk Road, and witnessing the vastness and grandeur of the Western Regions. In addition to a series of videos, notes, sketches, ink paintings, photography, and more from this journey will be published, collectively titled "Tianshan Ink Strokes."

This issue's records focus on the past of Turpan's Grape Valley and the local cultural relics.

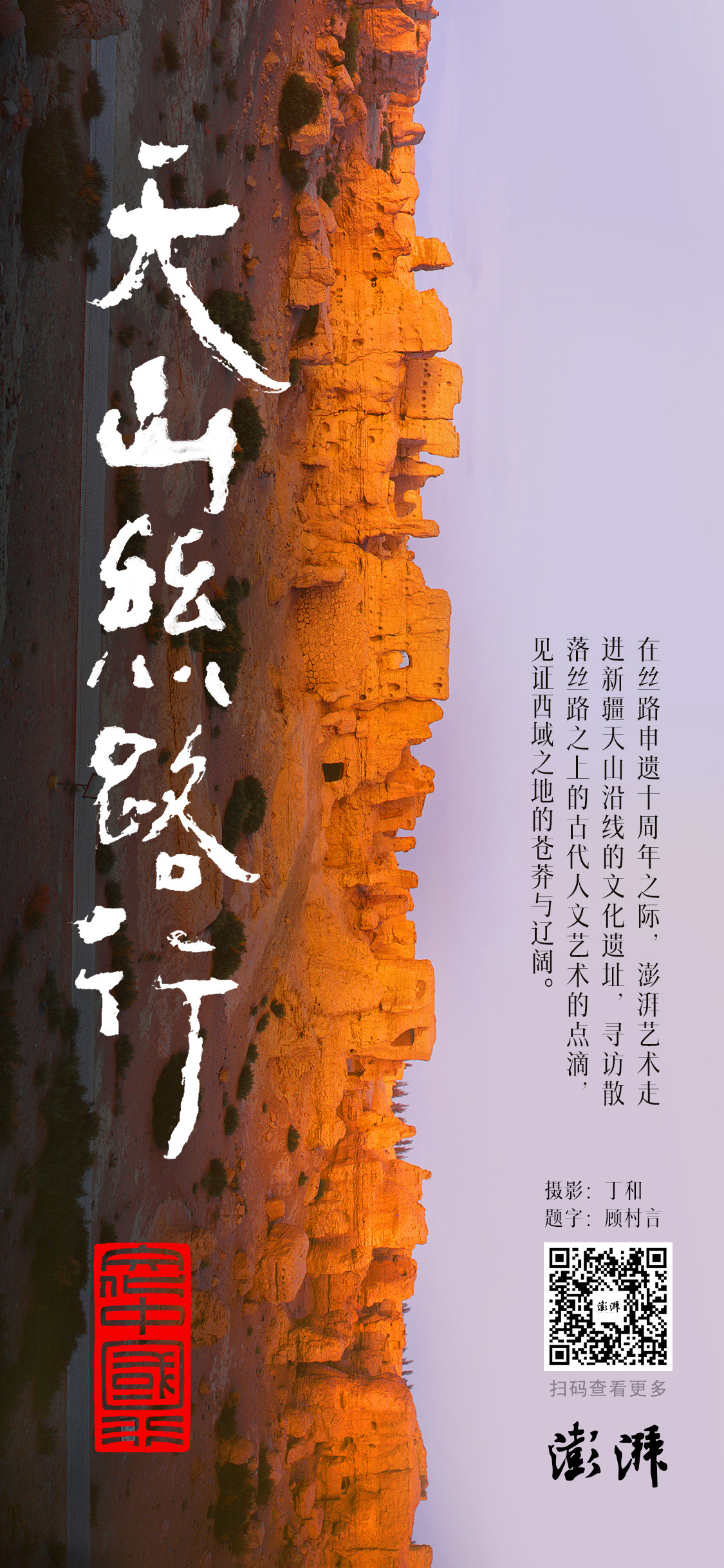

Poster for "Cultural China Journey: Tianshan Silk Road" (scan the QR code for more), Photography: Ding He Calligraphy: Gu Cunyan

The Distant Grape Valley

The grapes in Turpan are almost ripe.

The grapes of Turpan are mundane, joyous, and also melancholic. As a child, I listened to Guan Mucun's "The Grapes of Turpan Are Ripe." Her deep and rich voice flowed with sentimental melodies that seem to linger on, evoking a sense of nostalgia.

Perhaps seven or eight years ago, during my first visit to Turpan, I specifically chose a boutique guesthouse in Grape Valley to stay. During the day, I hired a taxi driven by a Uyghur driver named Khermu, traversing through historical sites and observing relics. In the evenings, I leisurely strolled through the night market at Grape Valley and by the creek, casually sitting down to eat a handful of grapes, order a bottle of beer, and enjoy a few skewers of grilled meat—so comfortable and liberating.

The cool breeze in Grape Valley at night is wonderfully refreshing.

It contrasts completely with the scorching heat of Turpan's daytime. Those days in Grape Valley felt like a dream. I remember meeting and befriending several people, touring Gaochang Ancient City and Astana together... Looking back now, those figures have become blurry in my memory, but I vividly recall the large, round moon, bright and yellow, hanging above the grape trellis by the creek.

When I left Turpan, it was in the morning. Khermu had promised to pick me up at the station, arriving much earlier than planned. He insisted on taking me to his home to pick grapes, saying I should take some with me.

His yard was spacious, with most of it covered by grapevines. The sunlight scattered into delicate fragments through the leaves, and the air was filled with the sweet scent of grapes. These dense summer fruits hung heavy, about the size of my index finger, each one glistening, transparent, round, and plump. As I popped one into my mouth, it had a crisp texture, and the juice burst forth, unleashing a unique sweetness and aroma that quickly filled my mouth.

These grapes tasted completely different from those in the markets. After picking a couple of bunches, Khermu thought it was too few and insisted on filling two bags to the brim.

With so many grapes, I returned to the guesthouse, planning to share some with the friends I had recently met, but they were still sleeping in, so I left the grapes on the windowsill and got into Khermu's car, and we left.

On the way back, I had a dream: those freshly picked grapes scattered everywhere, and the murals from Astana, also scattered about...

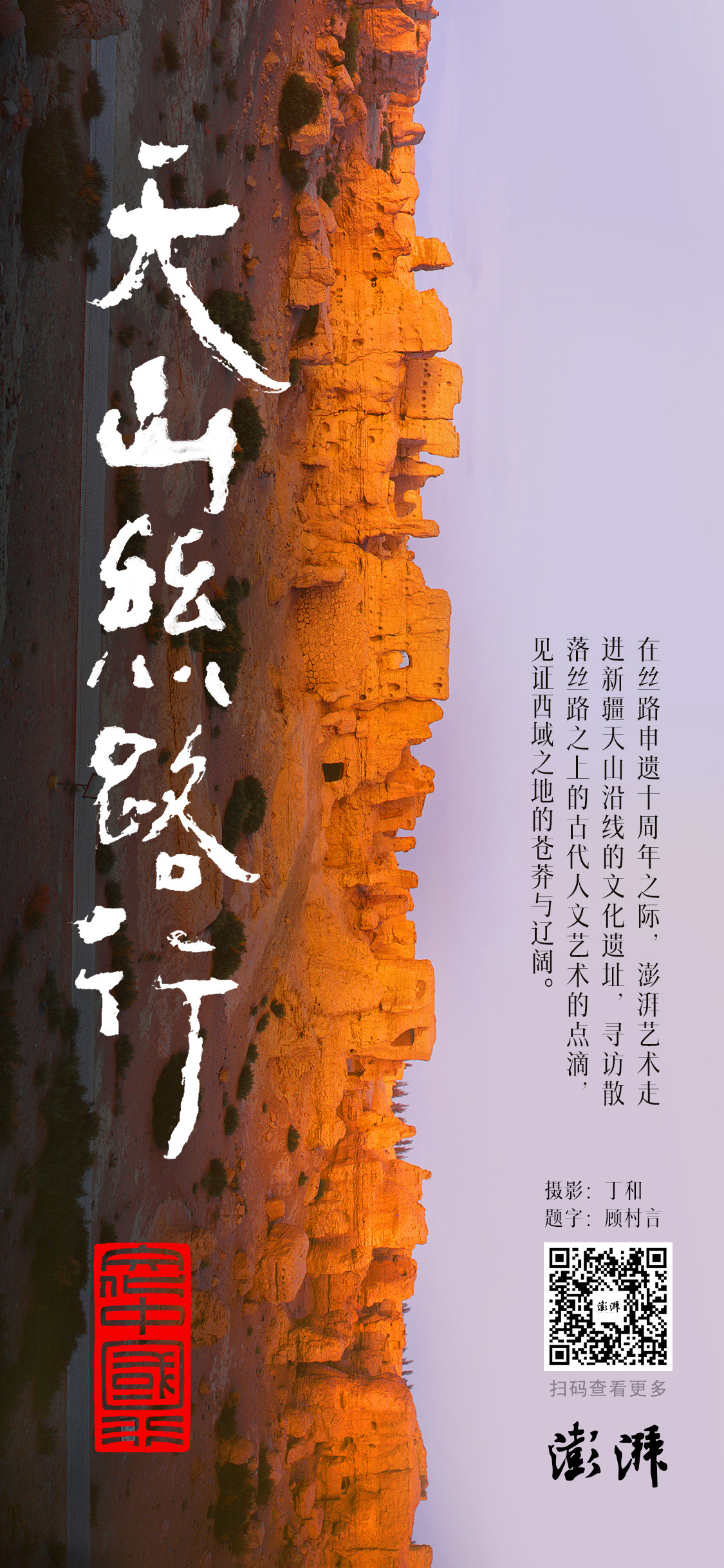

Pen sketch of Turpan Gu Cunyan

Years later, on a stormy night in Jiangnan, I unexpectedly reunited with friends from Turpan by a lake. We drank quite a bit of huadiao (a type of Chinese wine)—almost a bottle each—stumbling over our words, and somehow the topic of those grapes came up. I recalled that dream while sitting alone by the water, and inexplicably jotted down a few lines:

Can't remember, the distant Grape Valley

Distant Awa'erguli

The forgotten windowsill, those freshly picked grapes

Scattered across the ground.

Can't remember, tonight

Stumbling by the lake, each with a bottle of huadiao.

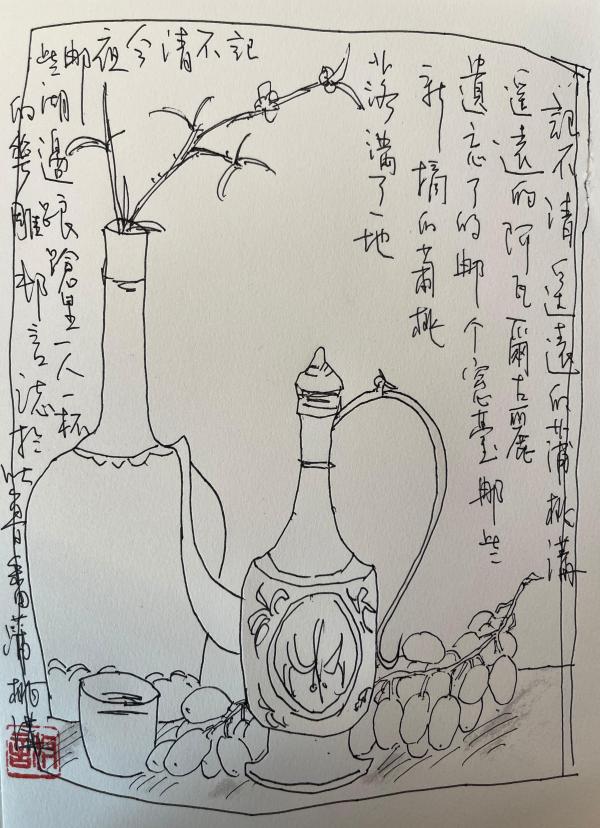

Detail of "The Pearls of Turpan Are Ripe" Gu Cunyan

Detail of "The Pearls of Turpan Are Ripe"

The Grapes of Turpan Are Almost Ripe

Upon returning to Turpan, I had nearly forgotten about Grape Valley.

It was on the way to the Jiaohe Ancient City, just before dusk, I caught distant glimpses of vast vineyards, almost like a sea of green. On a hillside in the distance, rows of beehive-like drying houses stood in earthy yellow tones, resembling castles set against the high blue sky.

Photographer Ding He exclaimed: "Stop! Stop the car!"

—He wanted to capture the images of the drying houses atop the grapevines.

The drying houses, primarily made of mud bricks, are designed specifically for drying raisins. Most have hollow flower hole walls—some square, some cross-shaped—for ventilation while avoiding direct sunlight. Inside, grapes hang, said to take about 40 days to dry. Whether green, red, purple, or black, they reach a semi-transparent state, chewy and sweet, quite aromatic.

At dusk, such an extensive vineyard with so many drying houses is indeed a rare sight.

Chasing the light, the photographer continually adjusted his position, finally capturing the picturesque scene with the distant grapevines and drying houses amid a watermelon field—titled "The Grapes of Turpan Are Ripe."

"The Grapes of Turpan Are Ripe" Ding He Photography

Ding He noted that this was the opening shot for this "Tianshan Silk Road Journey," fulfilling a craving that has lingered for years. "I can't even recall how many times I've been to Turpan. Each time, I made sure to photograph the grape drying houses, but it always ended up being weathered, with poor visibility, leaving me unsatisfied. This time, I finally got what I wanted and captured 'The Grapes of Turpan Are Ripe!'

In the twilight, each grape in the vineyard sparkled and glowed. Unable to resist, I picked a few; their taste was actually just a hint of sweetness—perhaps the photographer's naming was far too earnest; these grapes were not quite fully ripe yet.

Grapes of Turpan

A Day Without Grapes Is Unthinkable

There is a reason why the products of a region gain fame across the world.

In Xinjiang, the most famous saying goes: "Turpan's grapes, Hami's melons; Yecheng's pomegranates are the best." Turpan's grapes are rated number one; just look at the 2300-year-old grape vine in Turpan Museum (unearthed in 2003 near the Flaming Mountains' Yanghai Cemetery) to understand that its reputation is well-deserved.

The earliest written records of Viticulture and winemaking in the Western Regions date back to the Han Wudi period. "Records of the Grand Historian: The Biography of Dayuan" mentions Zhang Qian's travels to the Western Regions, stating: "On either side, they drink wine made from wild grapes, and wealthy families store up to 10,000 shi of wine; some even last for decades. The locals enjoy wine, and horses are fed alfalfa." The "Book of Han: Treatise on the Western Regions" also recorded viticulture and winemaking in the countries of Kema, Nandu, and Geshain.

This vine serves as a tangible testament to the grape-growing history of China, pushing back documented Viniculture by centuries.

"The Oldest Grape Vine" Gu Cunyan Illustration

The grape vine, resting silently in a glass case in the exhibition hall, is dark brown and over a meter long, adorned with four or five buds that seem to still be fighting for life.

The owner of the tomb was a person from the Chashi tribe, and the reason for including a grape vine in the burial could be that, in the afterlife, having a grape vine with you allows one to cultivate a vineyard.

For the Chashi people, how could a day go by without grapes?

Though the historical portrayal of the Chashi people is vague, this oldest grape vine brings them to life in an instant.

Additionally, the exhibition hall showcases two Han dynasty wooden crowns from the Chashi people that evoke the ancient style.

Chashi Wooden Crown Han Dynasty

Both wooden crowns were unearthed from the Shengjindian Cemetery near the Flaming Mountains of Turpan. The male crown is composed of thin wooden boards, shaped like a tall square prism with small holes for tying hair; the female crown resembles a hat, featuring two long extensions on either side, somewhat akin to the tail of a pheasant seen in traditional Chinese opera—an iconic look for heroic characters such as Zhou Yu or Mu Guiying, who exude power. Who knows if this is where the style originated?

While displaying the Chashi ancient crowns in the Turpan Museum, there are also character costume restoration images. Displeased with their rigid style, I humbly sketched these Chashi figures in opera character representations.

"Ancient Style of Chashi: Women Crowns" Part One Gu Cunyan Illustration

"Ancient Style of Chashi: Male Crowns" Part Two Gu Cunyan Illustration

The Past and Present of Grapes

Apart from the oldest grape vine, there is a myriad of grape-related artifacts excavated in Turpan.

Among them are dried grapes and grape seeds from the Tang dynasty, vineyard rental contracts, and grape paintings from the Wei and Jin periods... In the Kizil Grottoes near the Flaming Mountains, there are images of figures wearing floral crowns and long flowing skirts holding baskets of grapes, alongside cascading grapevines, reading as a scene filled with sweetness.

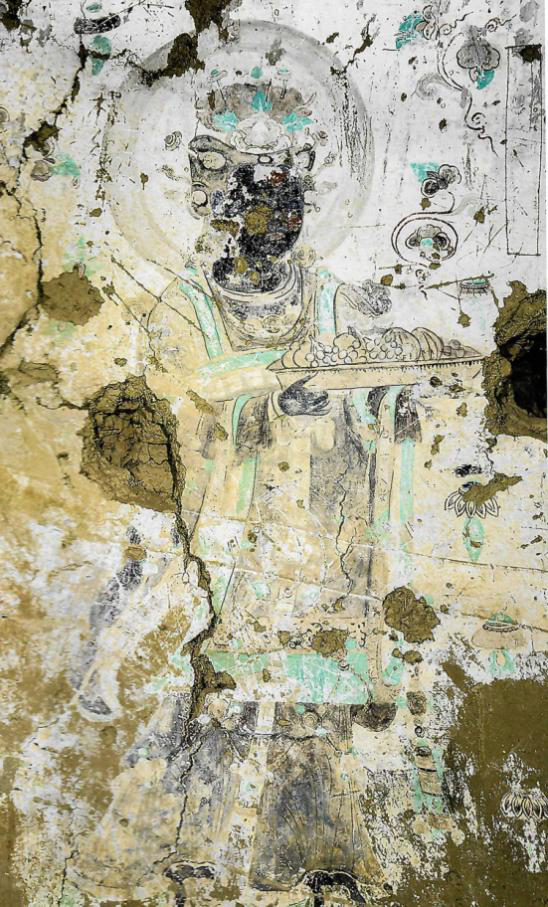

Offering Bodhisattva holding