Today marks the White Dew, one of the twenty-four solar terms. In some regions, temperatures remain relatively high; however, there is a saying: "On the night of White Dew and autumn wind, the geese fly south in formation." Another saying goes, "Grapes ripen after White Dew, red dates are harvested at the autumn equinox." After White Dew, the summer heat inevitably diminishes, and we gradually enter the fresh and crisp season of autumn.

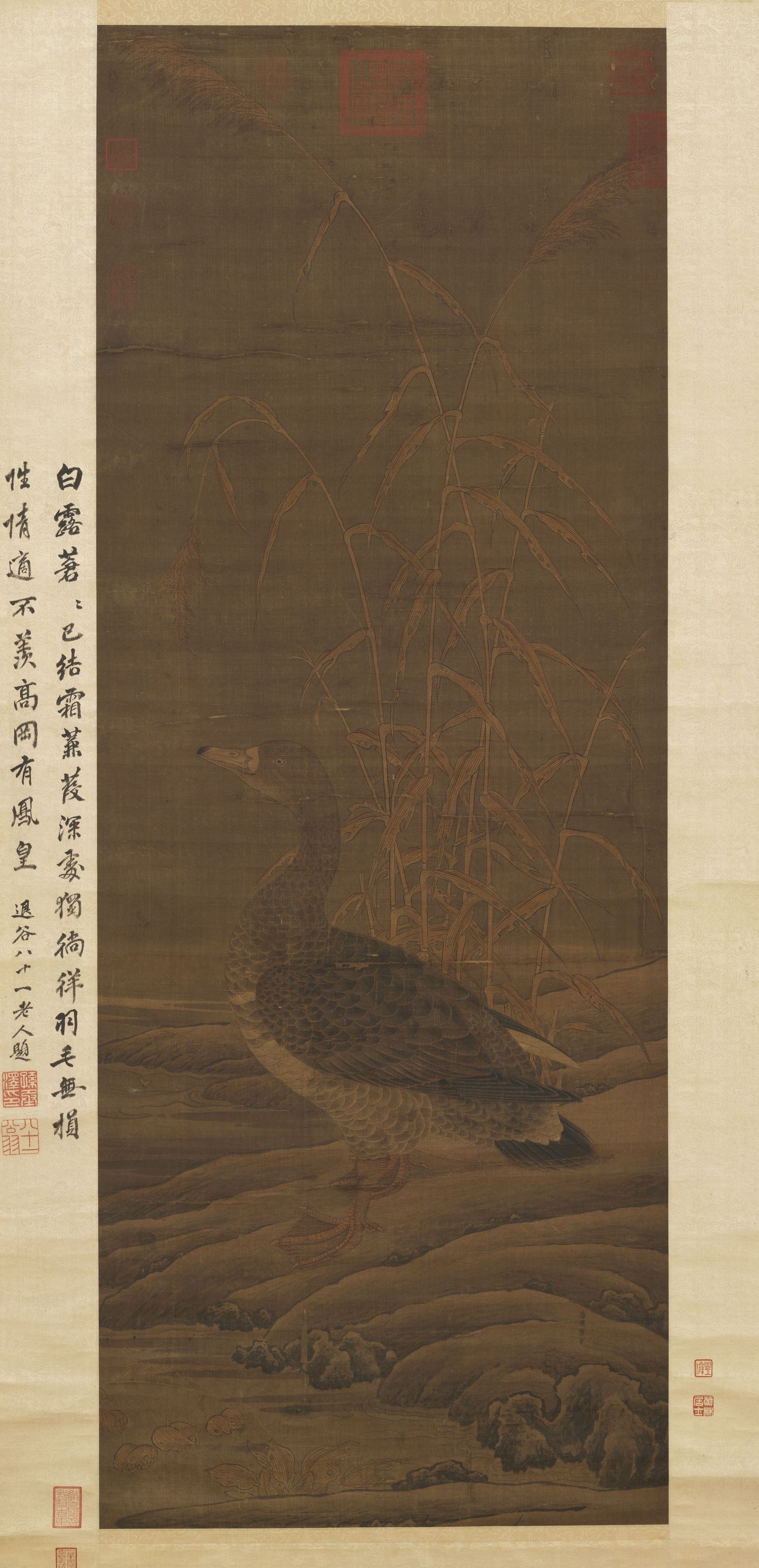

The beauty of White Dew is captured in the "Book of Songs" with the lines: "The reeds are lush, and the white dew appears like frost. The one I long for is on the other side of the water." Throughout history, renowned paintings and calligraphy feature scenes of reeds in the White Dew, misty waters, and the cold banks, displaying geese resting on the sands and wild geese soaring high. In a poem inscribed on the "Painting of Reeds and Geese" by Cui Bai from the Song dynasty, he writes, "The White Dew is already frosted, I wander alone among the deep reeds. No harm to my feathers, my spirit soars, I do not envy the mountains where phoenixes dwell." In Zhu Fei's "Geese Gathering at Reed Marsh," created during the Ming dynasty, the brushwork is delicate and free, with self-penned verses stating, "Who can compare to the dark geese over Xiangpu? They fly away and return to the azure sky."

Song Dynasty, Cui Bai, "Autumn River Hubei", Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

First, let’s examine the painting of geese during the White Dew season: "Autumn River Hubei" by Cui Bai from the Song dynasty (Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei), depicts yellowing lotus leaves and vibrant hibiscus flowers, radiating the beauty of autumn. Between the flowers, a wagtail leaps joyfully, while a jade-green bird rests quietly. Two wild geese flap their wings in mid-air, representing the vast expanse. Although the artist's seal is absent, it is traditionally attributed to Cui Bai.

Cui Bai (approximately 11th century) hailed from Haoliang (present-day Fengyang, Anhui), and his courtesy name was Zixi. He served as an artist in the painting academy during the reigns of Emperor Ren and Emperor Shen of the Song dynasty. He was renowned for his meticulous depictions of flowers and feathers, especially in portraying withered lotus and wild geese, though he also excelled in depicting Buddhist themes, figures, and mythical beings. It is said that he never sketched drafts; instead, he created strong, straight lines without the need for a ruler, achieving immediate strokes with his brush.

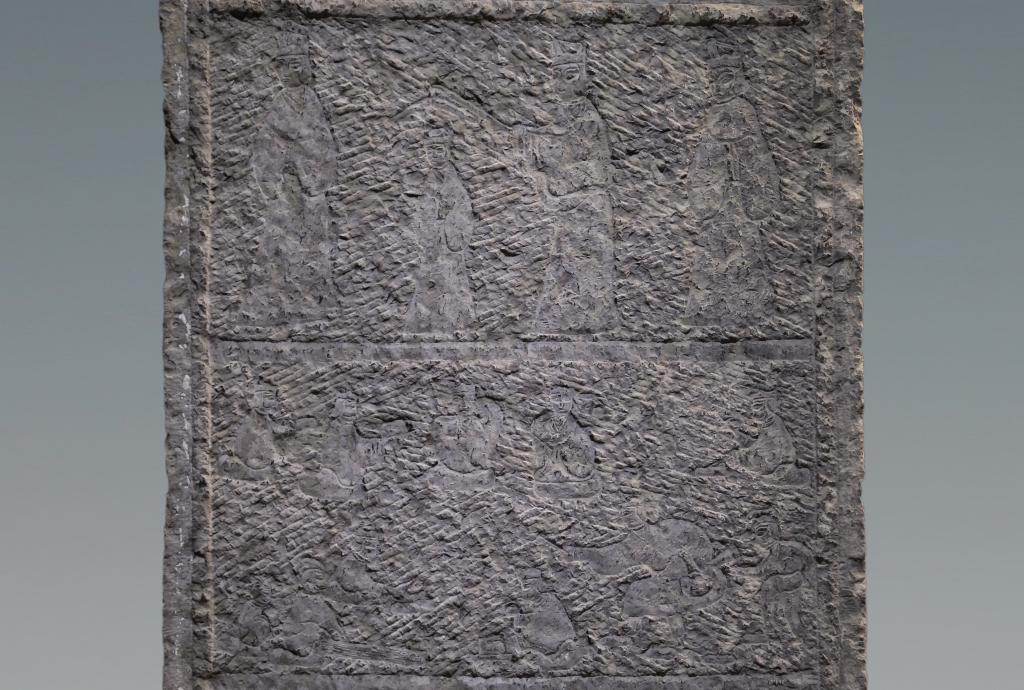

Song Dynasty, Cui Bai, "Reed Geese", Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

In another work, "Reed Geese," Cui Bai illustrates a solitary goose lingering among the water's edge and reeds. The goose's outline is initially sketched with contrasting shades of ink, then colored with washes of ink, filled with ochre and cobalt blue to showcase the glossy texture of its feathers. The light ink on the silk background makes the scene more distinct, enveloped with a feeling of coldness. On the rocky ledge, the inscription reads "Cui Bai of Haoliang."

Song Dynasty, Cui Bai, "Reed Geese" (Detail), Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

A Song dynasty painting titled "Autumn Pond with Twin Geese" depicts a tranquil corner of an autumn pond. Yellow reeds, red smartweed, and wilted lotus flowers create an intriguing contrast with white geese. Although this artwork features two geese, since geese and ducks belong to the same family, the ancients often referred to both collectively as 'geese,' giving rise to the title "Autumn Pond with Twin Geese." The painting is characterized by rich color and subtle ink accents, rendered in an elegant and realistic style, capturing lively expressions that reflect the artist’s keen observation of nature. This piece is a composite of two silk panels, composed in a wide-open format, embodying a sense of desolate water scenery, and is attributed to the Northern Song Dynasty's Huizong period (1102-1126), making it one of the rare representative works of Northern Song waterfowl art.

Song Dynasty, "Group of Geese by the Cold Pond", Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

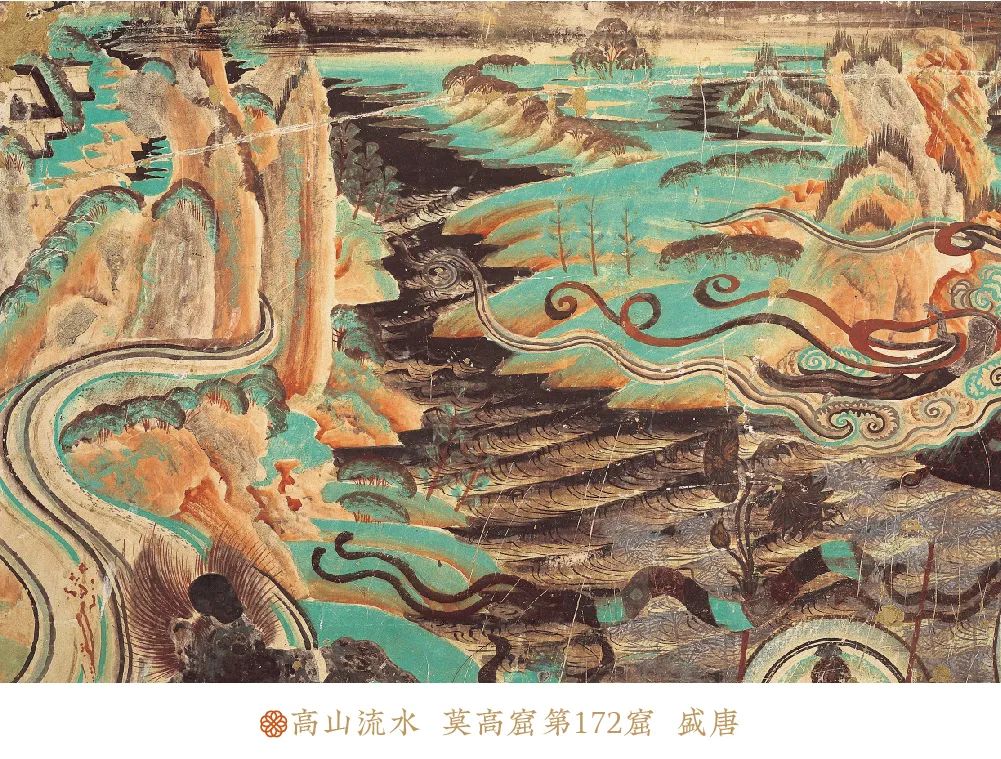

Numerous murals in Dunhuang are also related to White Dew. In the murals of Cave 172 of the Mogao Caves from the prosperous Tang dynasty, celestial maidens drift into autumn scenery, their garments swaying while their skirts lift in the wind. Behind her, a river winds down beside steep mountains. The trees on the mountains transition from summer's lush green to early autumn's rusty red, with a small temple hidden among the hilltop's foliage, appearing almost ethereal.

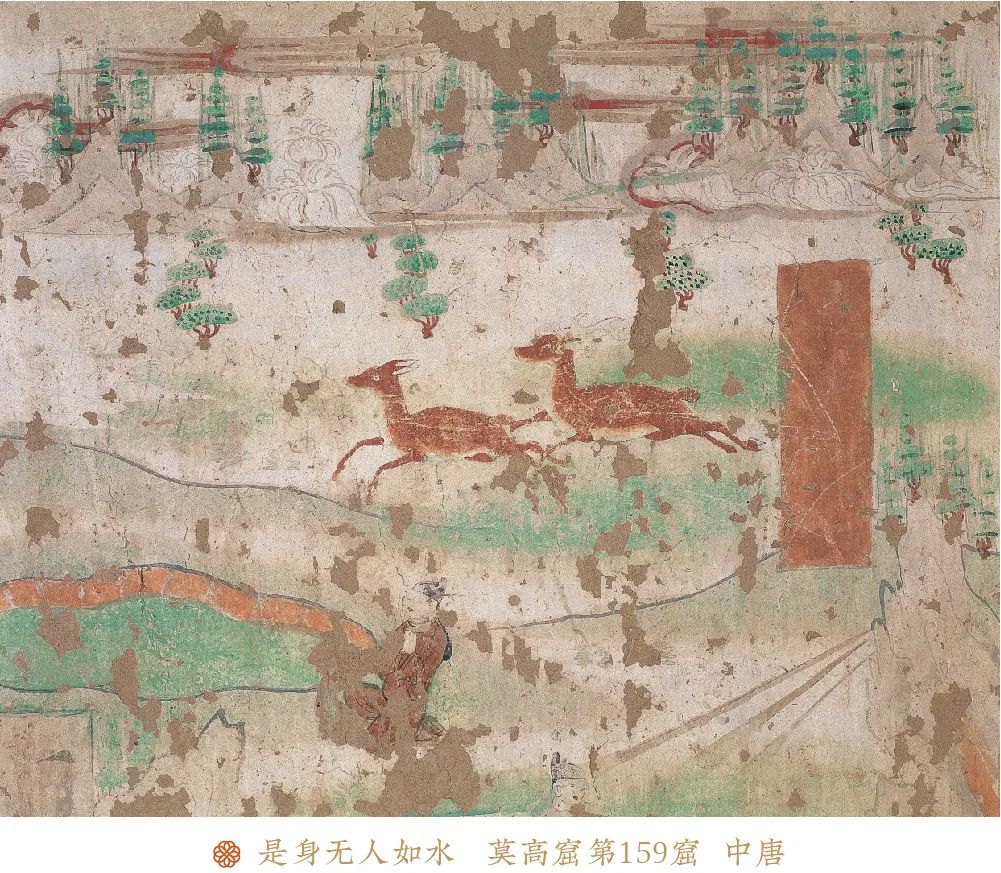

In the mural of Cave 159 from the middle Tang dynasty, a scholar sits in front of the water with his hands clasped, completely immersed in his own world. A deer gallops by, but he remains oblivious. Leisurely clouds drift by, unaware of existence or absence. A thousand years later, reflecting upon the murals during the White Dew season, the moist scent of the earth and the fragrance of osmanthus linger, and a drop of dew can cleanse one's spirit, rendering clarity in an instant.

Folklore states, "Grapes ripen after White Dew, red dates are harvested at the autumn equinox," highlighting that grapes at this time are the sweetest. Grapes have also become a classic motif in the Dunhuang murals and an important component of Dunhuang cave art.

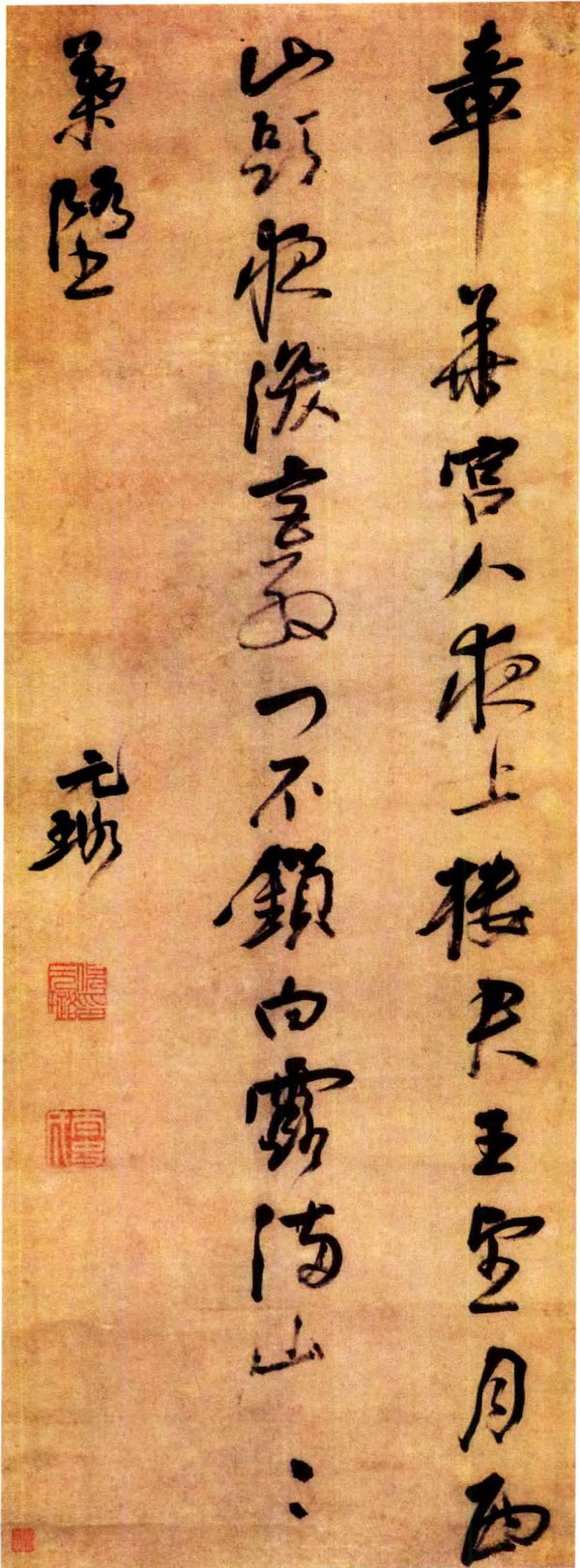

Additionally, references to White Dew can be found in calligraphy. For instance, Ni Yuanlu’s calligraphic poetry matches the poem’s mood harmoniously, evoking a sense of desolation: "The palace ladies at Zhanghua Pavilions ascend at night, the king gazes at the moon over the western hills. Late at night, the palace doors are unlocked, and the white dew fills the mountains as the leaves fall." Ni Yuanlu's calligraphy, influenced by Yan Zhenqing, exhibits a round and rich style that accentuates thick ink usage, earning him the title "The Prime Minister of Thick Ink." This letter particularly showcases his character—unconventional, with flashes of brilliance apparent in the strokes.

Ming Dynasty, Ni Yuanlu, Calligraphy of "The Palace Ladies at Zhanghua Pavilions Ascend at Night," Seven-Character Poem

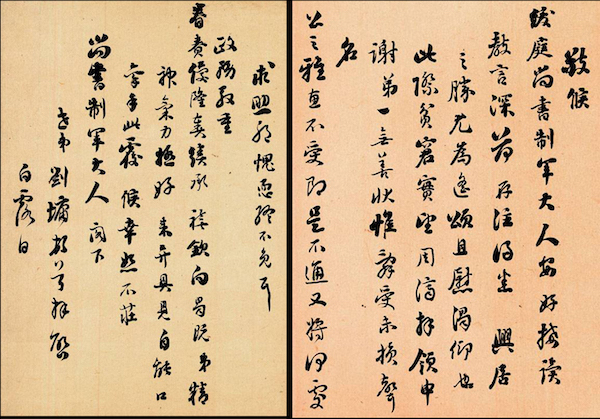

In the Qing dynasty, Liu Yong wrote a letter of appeal during White Dew to the "Honorable Military Official of the Ministry of War": "At this moment of poverty, I sincerely hope for assistance and express my gratitude. I possess no skills, and can only decline to receive assistance that would tarnish my reputation." Liu Yong’s calligraphy, derived from Yan Zhenqing, appears softer and rounder compared to Yan's. He favored using thick ink, hence the moniker "Thick Ink Prime Minister." This letter reveals his character, exhibiting a nonconformist style while showcasing remarkable penmanship.

Qing Dynasty, Liu Yong, Letter

(This article synthesizes information from the National Palace Museum in Taipei, Dunhuang Academy, and previous reports from The Paper.)