According to Pengpai News, the exhibition "The Princess Arrives! Portraits of Princesses in Qing Dynasty Documents" is currently on display at the National Palace Museum in Taipei. This exhibition mainly features Qing Dynasty archival documents from the museum's collection, and is divided into several sections including "Daughters of the Emperor," "Unpacking Family Assets," and "Marriage Alliances," showcasing the identity system, interpersonal relationships, and stories of Qing princesses, as well as their roles and significance in the political operations of the Qing Empire.

In a traditional male-centered society, women often existed as a relatively silent group. However, how did women establish their place in history? What footprints have they left behind? This exhibition at the National Palace Museum approaches these issues from the theme of women's history, using the familiar subject of "Qing Dynasty princesses," which still resonates in novels and dramas, to explore these topics.

The exhibition focuses on Qing Dynasty archival documents held by the National Palace Museum, presenting the identity system, interpersonal relationships, life stories of princesses, and their positions and significance in the political operations of the Qing Empire. Among these various documents, we can observe what voices and postures people beyond the mainstream historical narrative have left behind in both the past and present.

Daughters of the Emperor

The term "princess" in Chinese has existed since at least the 5th century BC during the Warring States period. Originally referring to the daughters of monarchs or feudal lords, it later became a title exclusive to the daughters of emperors, and can be seen in the East Asian Chinese character culture circle, including in China, Korea, and Vietnam.

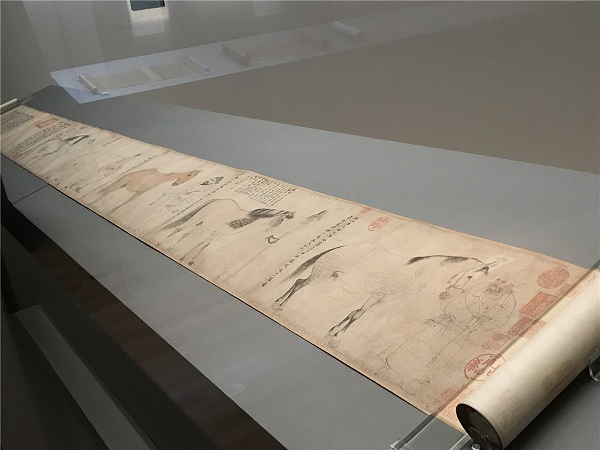

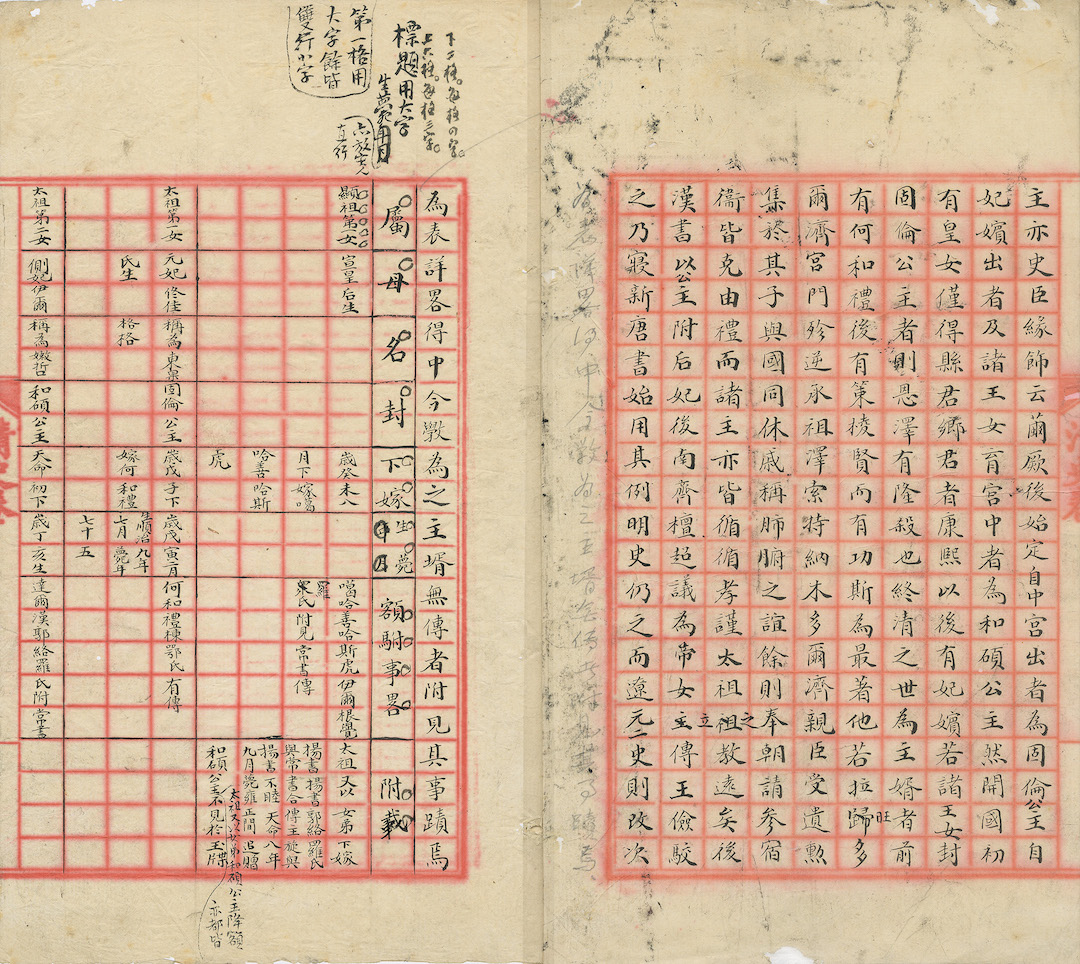

"List of Princesses"

"List of Princesses"

"List of Princesses"

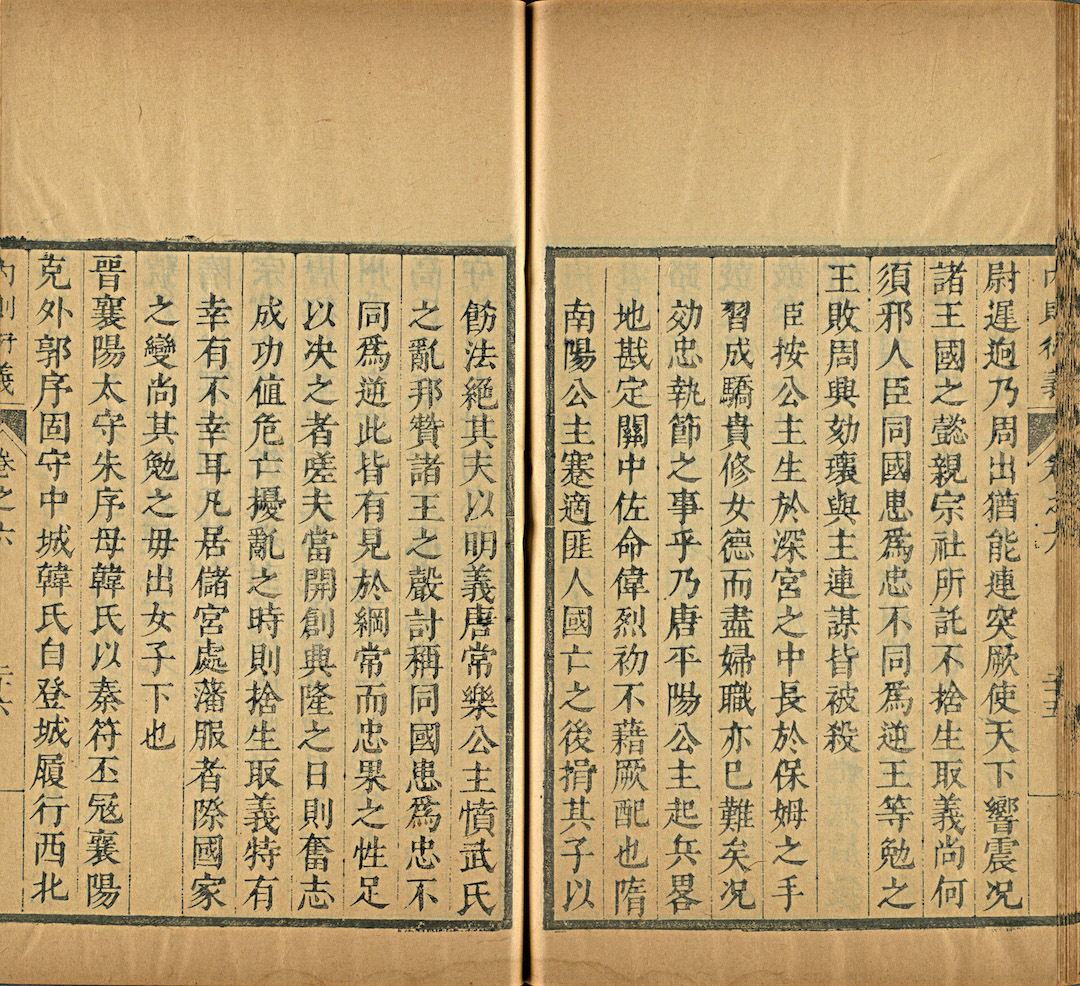

"The List of Princesses" is one of the draft copies of the "Draft History of the Qing," documenting information about 95 Qing princesses. The list features eight columns, with the "Name" column noting the official name or title of each princess; however, only eight princesses before the reign of the Taizong (Hong Taiji) have their details filled in, while the others remain blank, making this the column with the least information.

Manchu females originally had their own names, but after establishing dominance over the central plains, emphasis on female names gradually diminished. Thus, unlike the nobility who generally lived under their given names, the names of princesses are rarely seen in documents, most often only referred to by birth order or titles granted by the empire, seemingly reflecting their responsibilities tied to the empire’s foreign relations.

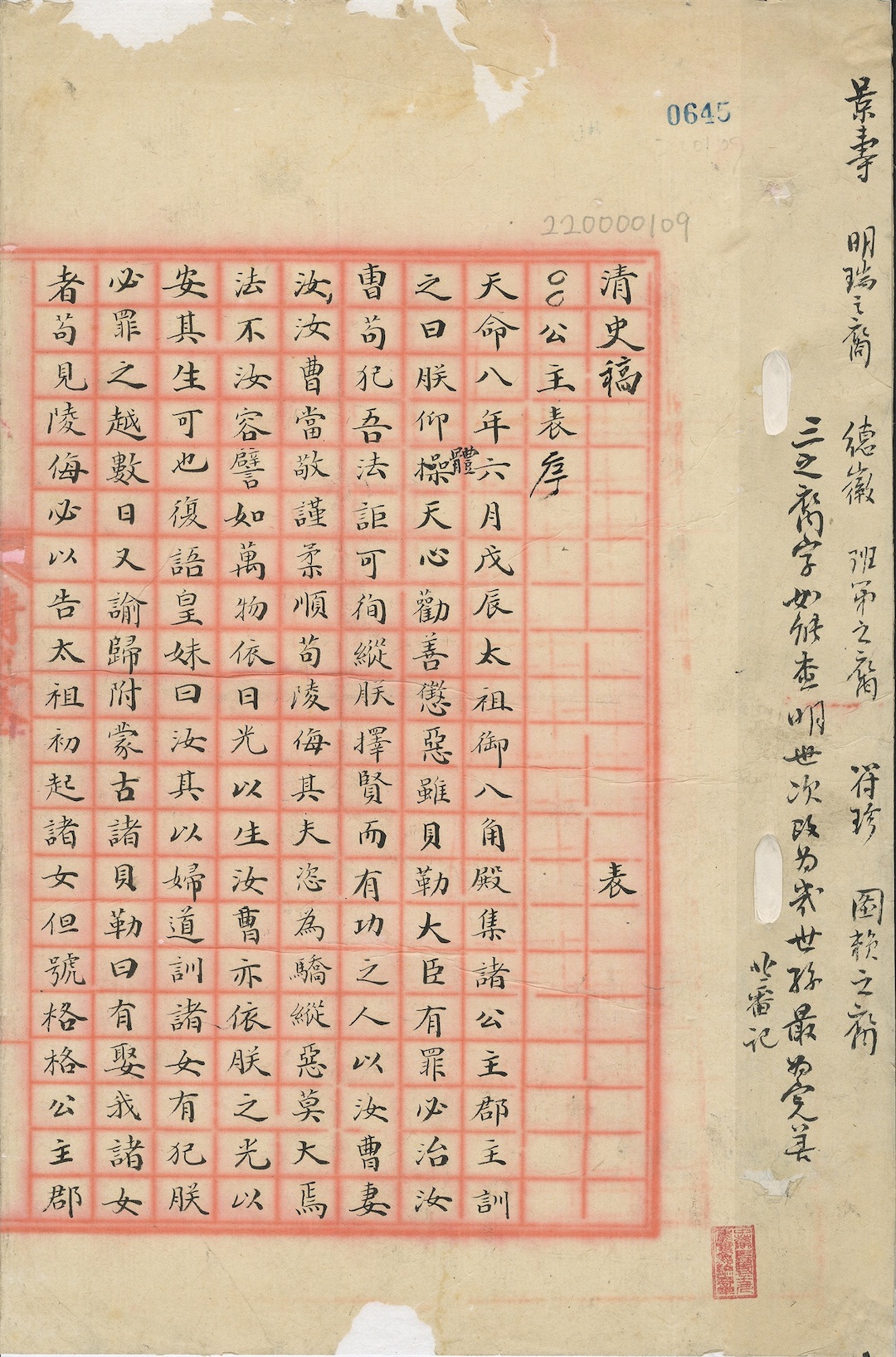

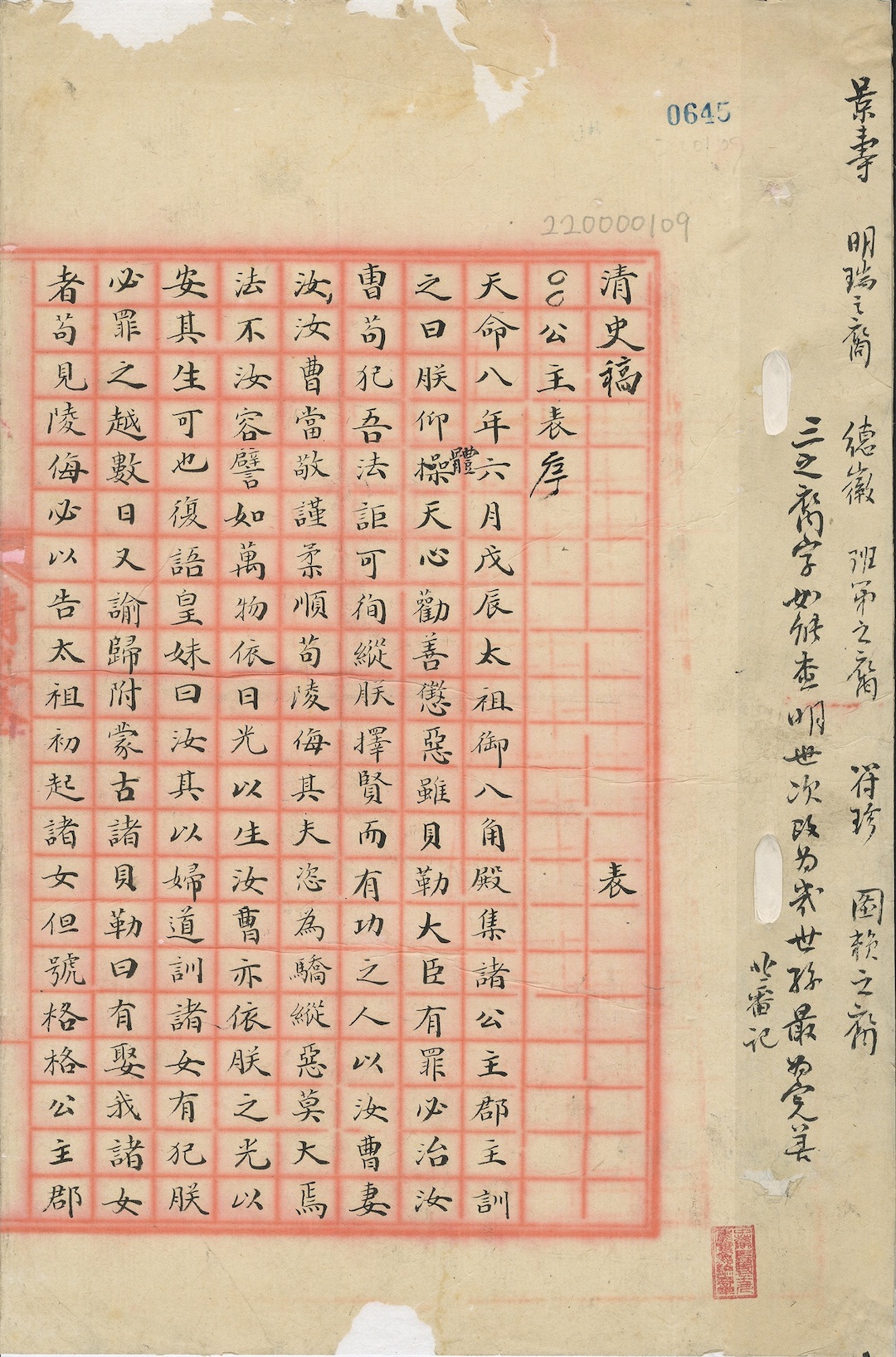

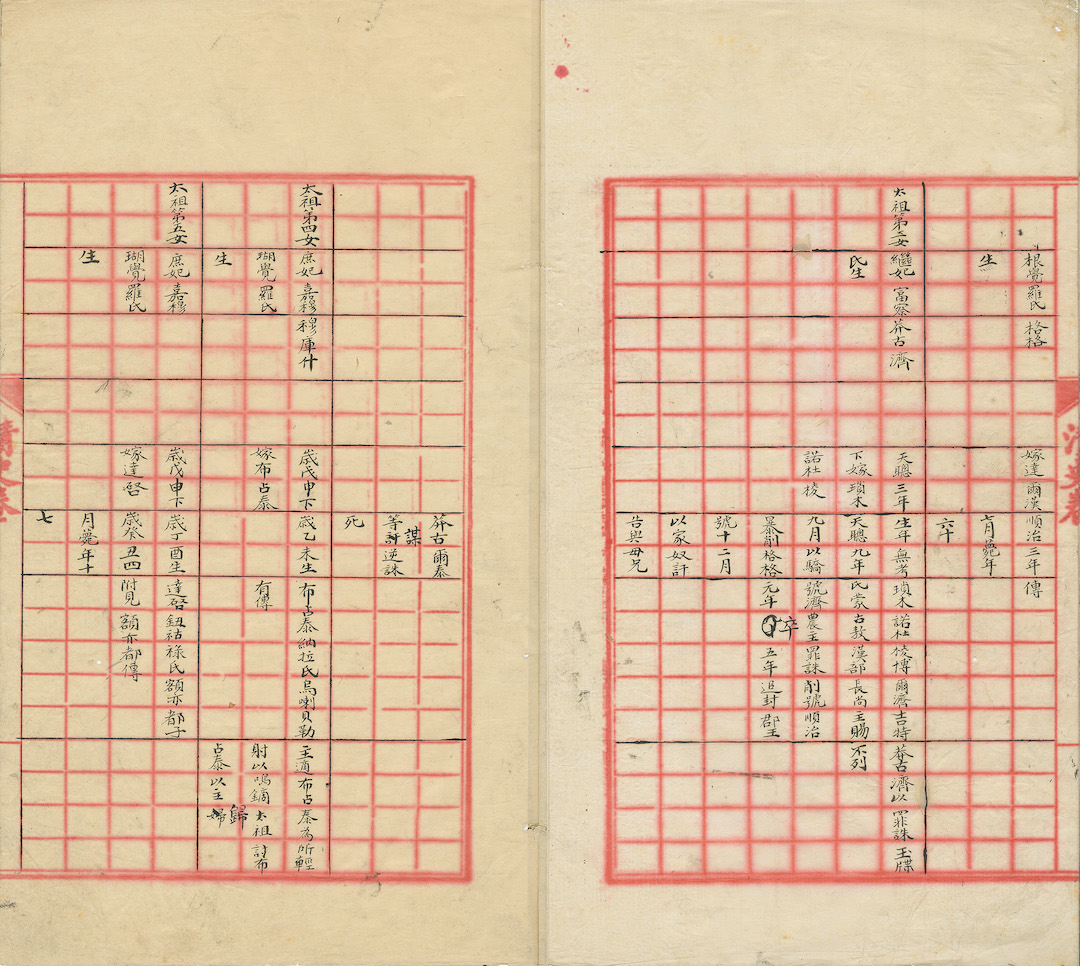

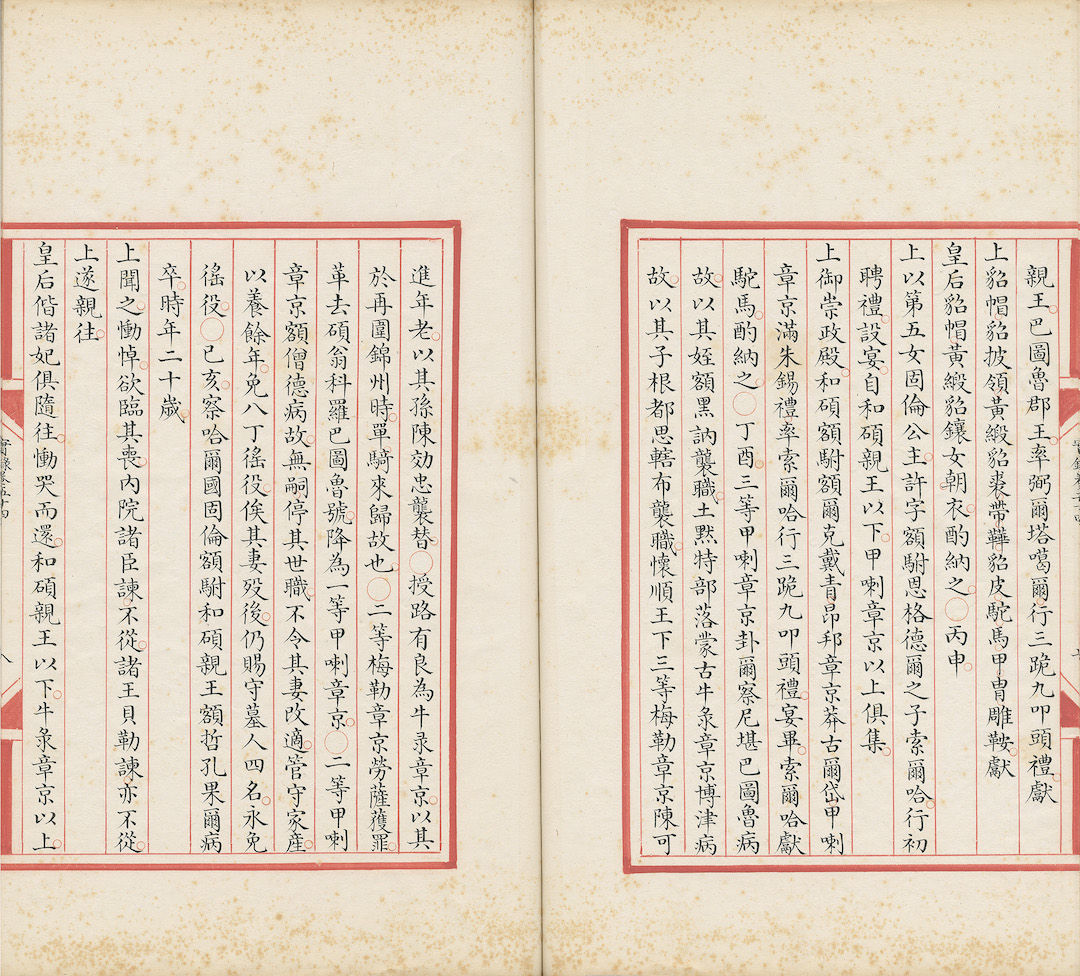

A record of bridal gifts sent by the husband of Princess Atu in 1641

Included in the "Veritable Records of Emperor Taizong of the Great Qing," collated by Chen Mingxia and others (initial compilation in 1655) and revised by Oertai and others (first revised in 1740), Chinese red satin edition, early compilation version, recompiled during the Qianlong period.

A record of bridal gifts sent by the husband of Princess Atu in 1641

Included in the "Veritable Records of Emperor Taizong of the Great Qing," collated by Chen Mingxia and others (initial compilation in 1655) and revised by Oertai and others (first revised in 1740), Chinese red satin edition, early compilation version, recompiled during the Qianlong period.

The fifth daughter of Hong Taiji, Princess Atu, is often referred to as the "Gulun Shuhui Princess" in later accounts. The initial compilation of the "Veritable Records" includes a description of the process through which her husband, Suoerha, sent bridal gifts in 1641, but the princess's actual name is rarely mentioned. In the later recompiled version during the Qianlong period, her actual name was removed and changed to "Fifth Daughter, Gulun Princess."

The initial compilation mostly translated early Manchu original documents, retaining many actual names of Manchu women, including Princess Atu's actual name. However, after the Manchus dominated the central plains, an emphasis on female names diminished, and Atu's name was deliberately altered. These two versions of the "Veritable Records," with their differing styles and content, subtly reflect the process of cultural and traditional changes in Manchu women's status.

Gold basin, commissioned by Empress Ulan of the Niohuru clan in 1831.

Commissioned in 1831 by Empress Ulan of the Niohuru clan (the mother of Emperor Xianfeng, later Empress Xiaoqian Cheng); according to Emperor Xianfeng, he used this basin shortly after his birth in 1831. After the death of Niohuru in 1840, Emperor Daoguang issued an edict stating that from then on, all newborn princes, grandsons, great-grandsons, and princesses could use this basin as designated by the internal palace head. However, there is currently no evidence confirming that any young princesses actually used it. What can be confirmed is that every young princess entered this world amid blessings and praises from many, and received their first ceremonial rites within such a golden basin, subsequently stepping into their royal lives.

"Inner Regulations and Interpretations" compiled by Fu Yijian and others, published in 1656 (13th year of the Shunzhi reign) by the Imperial Ministry.

Princesses grew up in the palace and were expected to receive an education during their schooling years; however, unlike princes who had a comprehensive education system and documented records, the details of when, where, and how princesses received their education are extremely limited due to the lack of documentation. "Inner Regulations and Interpretations" records multiple accounts of princesses, indicating that its readers likely included royal daughters, thus providing some indirect clues about their education.

As members of the royal family, princesses were destined to shoulder the responsibility of forming marriage alliances for the empire. The content of "Inner Regulations and Interpretations" suggests that one of the expectations or guidelines for palace education of princesses may be to prepare them for duties serving the empire.

Unpacking Family Assets

Although princesses were traditional women, their status as royal family members granted them relatively considerable assets and power of usage.

These assets—comprising money and various movable and immovable properties—stemmed from the royal planning and allocation. They primarily served to supply the daily lives and expenses of princesses; at the same time, they were also associated with the imperial system, Manchu women's cultural life, and the symbolic meaning of the princess's status.

The family assets of princesses present a unique material culture; many details of their lives are woven into it.

Portrait of Princess Shouzang Heshun, the fifth daughter of Emperor Daoguang, 19th century colored silk hanging, collection of the National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution.

The figures in the painting of "Portrait of Princess Shouzang Heshun," supposedly a Qing princess, are characterized by differing interpretations regarding whether they depict Princess Shouzang Heshun or Princess Shou'en, the sixth daughter. Surviving portraits of Qing princesses are quite rare, and this is one of the invaluable pieces. Additionally, Qing princesses rarely left much information about themselves in history; this portrait uniquely documents the princess's face and demeanor through its realistic nature. The detailed features of clothing, accessories, and hairstyles in the painting are also worthy of appreciation and interpretation in relation to Manchu culture.

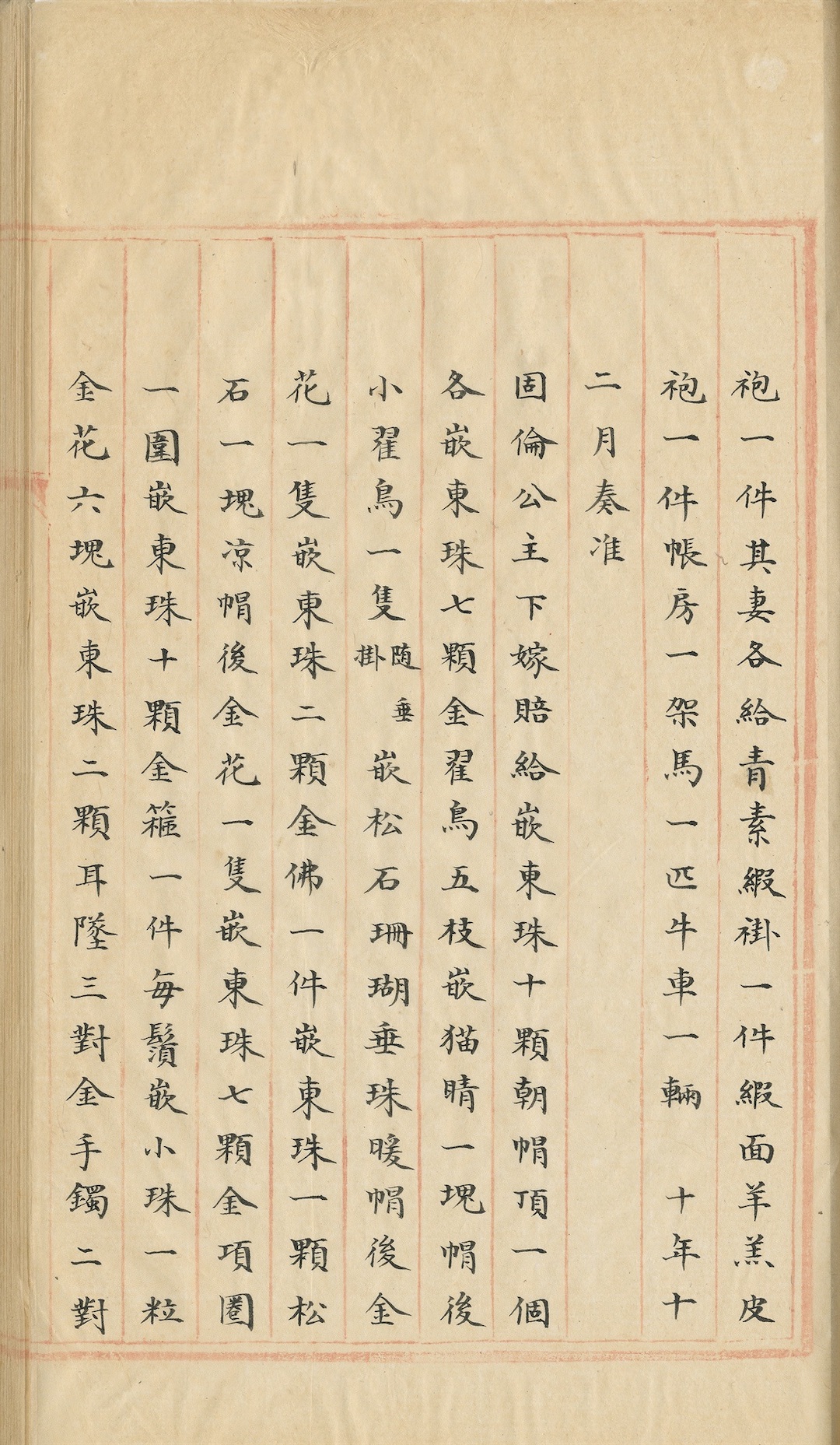

List of dowry items for Gulun Princess

Included in "Current Regulations of the Grand Council," compiled by the Grand Council, late 18th to early 19th century.

List of dowry items for Gulun Princess

Included in "Current Regulations of the Grand Council," compiled by the Grand Council, late 18th to early 19th century.

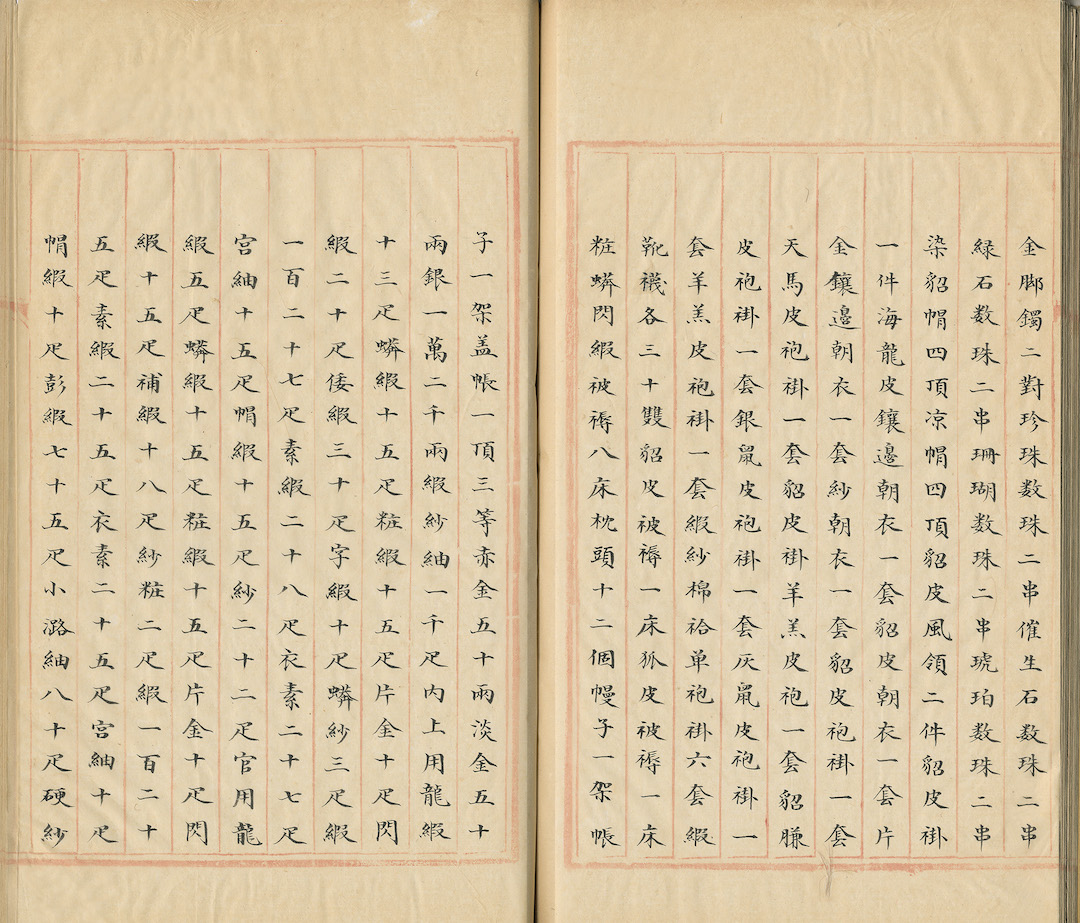

At the beginning of the Qing Dynasty, there were no fixed regulations regarding the contents of a princess's dowry, which were later standardized by Emperor Qianlong. This specific list of dowry for the Gulun princess was approved in December of the tenth year of Qianlong (between late 1745 and early 1746), detailing nearly 300 items in name and quantity, spanning categories including clothing, accessories, gold and silver items, various daily necessities, textiles, livestock, etc., showcasing the rich assortment of dowry items for the Gulun princess. Items for her husband, wet nurse, and caretakers were also listed.

The princess's dowry not only provided material resources for her future生活 but also symbolized the grandeur and dignity of the Qing royal family; these items were planned with the princess at the center, and a close reading of the various items reveals insights into the material and cultural lives of Manchu noblewomen.

Gold crown inlaid with lapis lazuli, around the 18th century.

Manchu women would wear headbands as decorative headgear, referred to in Manchu as gidakū, and in Chinese as "hairband," "headband," or "forehead band." The headband accessory in the formal attire of noble women in the Qing Dynasty is called a "gold crown." The Gulun princess's dowry list specifies that it includes "one gold crown inlaid with ten pearls."

This gold crown inlaid with lapis lazuli in the museum's collection comprises a total of ten gold clouds and ten pearls, and was recalled by the Grand Council in 1819; it is presumed to date back to the 18th century. This ten-pearl style gold crown should match the format listed in the Gulun princess's dowry list.

Jade prayer beads, Qing Dynasty relic.

In the Gulun princess's dowry list, there are entries for "numbers of various pearl strings," "birth stones (lapis lazuli) strings," "green stone strings," "coral strings," and "amber strings," with two strings each for five different materials, while the so-called "green stone strings" likely refer to this particular piece made primarily of jade (green jade) beads.

Examples of prayer beads mainly made of jade are rare, and green jade is even less common. During the mid-to-late Qing Dynasty, in the Daoguang and Tongzhi eras, jade jewelry became increasingly prevalent; this prayer bead piece reflects the popularity of jade in the 19th century, while also indicating that the materials for the princess's prayer beads may have been more diverse.

Marriage Alliances

For many, marriage is a significant life event; however, for princesses, it may be regarded more as an ultimate task that must be fulfilled.

Throughout human history, many marriages were not born from love but were strategic, aimed at personal, familial, or national interests. The Qing Empire, with its diverse regions and demographics, also employed marriage alliances