How can pictures tell stories? Which stories are given the opportunity to be visualized? How should story paintings be understood? The National Palace Museum in Taipei recently launched a new exhibition titled “The Language of Paintings: Pictures That Tell Stories,” focusing on “story paintings” or “narrative paintings” as the main exhibits, highlighting how “images” transcend textual descriptions. By showcasing 47 different narrative paintings from various dynasties, the exhibition narrates rich history that is both familiar and evocative, such as the Dunhuang murals depicting the life of Prince Sudhana, “Wen Ji Returns to Han,” “Three Visits to the Thatched Cottage,” “A Snowy Night Visit to Dai,” “Journey to the West,” and more.

How can pictures tell stories? When artists recreate or interpret stories through images, their primary goal is often to ensure that viewers can recognize the depicted content. Given the constraints of size and form (scroll, handle, album), artists must select representative plot points, arrange appropriate settings, and design characters and their actions to successfully convey the story.

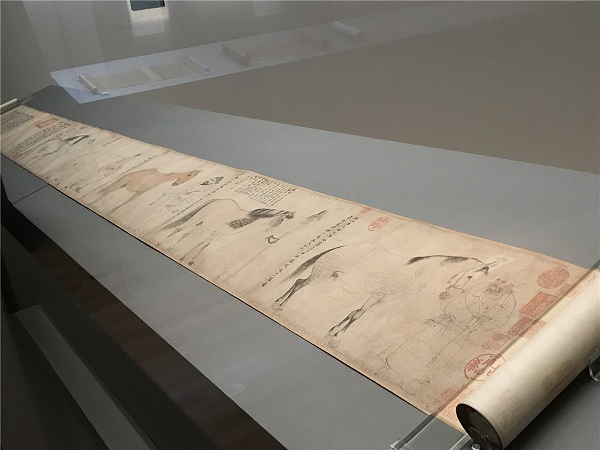

Exhibition scene

Why paint these stories? Which stories can gain the chance to be visualized? Who are they painted for? By judging and categorizing the themes of these paintings, one can attempt to deduce the artist’s intention and mindset at the time of creation, perhaps even feeling a sense of cultural identity that has persisted through generations. This offers another remarkable experience in appreciation.

How should story paintings be understood? The more relevant historical and literary knowledge an observer possesses, the higher the likelihood of correlating elements within the painting to the correct textual narratives. If an observer lives in the same era as the artist, the similarities in perceptions make it easier to grasp the choices and expressions in the artwork. However, how much can contemporary viewers discern?

Through this exhibition, not only can one appreciate how artists craft captivating narratives using images, but it can also assess whether viewers can transcend time and space to receive the rich messages the creators wish to communicate.

The Powerful Narrative Force of Images

Images with “stories” appear in various forms across diverse media. Some images are specifically designed to serve “stories,” such as stone carvings depicting loyalty and righteousness in tomb chapels, the Buddhist life story murals of Dunhuang, illustrations in the Lotus Sutra, and other historical events. But there are also images that were not originally meant to convey “stories,” such as the accompanying illustrations of classics like the “Classic of Filial Piety” and the “Book of Songs,” which due to their strong narrative quality, can provide viewers with a sense of story beyond the text itself.

Han Dynasty Wu Family Shrine image stone carving rubbings

The Wu Liang Shrine from the Han Dynasty dates back over 1900 years and features shadow-like stone carvings that decorate the entire space. The rubbings displayed in this exhibit illustrate seven stories of loyalty and righteousness, including "Old Lai Entertaining His Parents," “Jing Ke’s Assassination of the Qin King,” among others.

In a single scene, the artist employs the relationships among characters to guide the viewer's understanding of the story, supported by descriptive text. Many explosive character actions retain intricate details. For instance, in the left section depicting “Jing Ke’s Assassination of the Qin King,” even Jing Ke's hand gestures and the actions of the Qin King's guards are meticulously illustrated to convey details beyond the textual narrative.

Republic of China, Zhang Daqian, Copy of the Dunhuang Mogao Caves

Republic of China, Zhang Daqian, Copy of the Dunhuang Mogao Caves

Republic of China, Zhang Daqian, Copy of the Dunhuang Mogao Caves

Republic of China, Zhang Daqian, Copy of the Dunhuang Mogao Caves

Republic of China, Zhang Daqian, Copy of the Dunhuang Mogao Caves

Republic of China, Zhang Daqian, Copy of the Dunhuang Mogao Caves

Republic of China, Zhang Daqian, Copy of the Dunhuang Mogao Caves

Republic of China, Zhang Daqian, Copy of the Dunhuang Mogao Caves

Republic of China, Zhang Daqian, Copy of the Dunhuang Mogao Caves

Zhang Daqian’s “Copy of the Dunhuang Mogao Caves,” specifically the section depicting the “Offering of the White Elephant,” is a reproduction of a mural from the 6th century. The mural originally consists of three tiers that sequentially portray the story. The scenes are separated by mountains or architecture, showing lively and animated stances of the characters. Zhang Daqian followed the layout of the original mural while arranging the narrative from left to right, differing from the typical viewing direction of handscrolls, which is from right to left.

The exhibition showcases the segment where Prince Sudhana offers the white elephant. An enemy state deliberately sends eight Brahmins to request the priceless white elephant, said to secure victory in battles, from the benevolent Prince Sudhana. Despite agreeing to give it up, the prince ends up being exiled.

Later Qin, Translated by Kumarajiva, Lotus Sutra, Paper, book form

The two illustrated pages belong to the frontispiece of volumes one and seven of the Lotus Sutra. On the right side of the image, Shakyamuni Buddha and his retinue are depicted larger, adhering to the tradition of emphasizing important figures in artworks. Unlike earlier Dunhuang murals that often framed different stories or plots using mountains and stones, the frontispiece artists juxtaposed multiple stories within the same landscape scene, allowing characters to focus on their respective narratives. This set of frontispieces successfully conveys Shakyamuni Buddha preaching the Lotus Sutra and its contents, creating a harmonious and unified scene.

Attributed to Song Gaozong, Illustrated Classic of Filial Piety by Ma Hezhi (chapters on opening the subject and serving the ruler), Silk drawing, book form

Attributed to Song Gaozong, Illustrated Classic of Filial Piety by Ma Hezhi (chapters on opening the subject and serving the ruler), Silk drawing, book form

The “Classic of Filial Piety” records Confucius’s (551-479 BC) teachings on the principle of filial piety. The first scene depicts Confucius surrounded by his disciples, sitting sideways on a couch, along with Zengzi (505-432 BC) kneeling in front, akin to a simplified Buddhist-style frontispiece scene but from a Confucian perspective.

The fifteenth scene, dealing with “Serving the Ruler,” showcases a palace where the ruler is situated, with only a willow tree separating it from an official’s garden. It is unrealistic for these two entities to be so close, and the proportions they occupy in the painting suggest that the artist is interpreting the text segment’s phrase “In thought, serve loyally; in retreat, ponder your mistakes.”

This album, differing in style from that of the Southern Song court painter Ma Hezhi (who was active around the 12th century), is likely attributed to a later Song artist.

Qing Dynasty, Compilation by Hongli, Royal Poetry and Paintings of the Classic of Poetry (Qi Feng's Fu Tian and Bin Feng's July), Paper, book page format from Qianlong period

Qing Dynasty, Compilation by Hongli, Royal Poetry and Paintings of the Classic of Poetry (Qi Feng's Fu Tian and Bin Feng's July), Paper, book page format from Qianlong period

The “Classic of Poetry” is the earliest anthology of poetry, containing 305 poems written between the Western Zhou and the middle of the Spring and Autumn period (approximately the 11th to 6th centuries BC). Many poems use subtle imagery to express concealed opinions or emotions. Ma Hezhi, a talented humble official and painter from the Southern Song (who was active around the 12th century), created classic illustrations for the “Classic of Poetry.” The Qianlong Emperor of the Qing Dynasty (1711-1799) commissioned court painters to replicate Ma Hezhi's “Classic of Poetry” illustrations and to restore the incomplete parts. What is displayed here are two pages from the Qianlong period's duplicated works.

“Fu Tian” includes ambiguous poetic phrases that convey deep longing and anticipation for reunions. How to depict ‘longing’ from the lines? In the painting, the sloping hillside reflects the myriad mountains and rivers, symbolizing the scholar’s yearning for friends far away. This visual narrative cleverly conveys the lyrical content of the poem.

“July” encompasses a lengthy description of farmers' main tasks throughout the year. How much content can be captured in a small album page? The artist decisively uses clouds and trees to split the image into three sections, illustrating watching the stars at night, farming and collecting crops, and a year-end banquet scene from right to left. The banquet scene suggests that the painting does not merely replicate the text. The artist cleverly arranges a music and dance scene not mentioned in “July” at the bottom left corner, conveying a hope for educating the populace through rites and music.

The Essential Function of Images from a Confucian Perspective: Cultiv