Today marks "Frost's Descent," one of the 24 solar terms. Frost's Descent is the beginning of the frost season in the year. The Tang dynasty poet Bai Juyi wrote: "Clear and chilly, morning frost descends, a gentle breeze begins to stir. In the center, the red leaves unfold, at the corners, green duckweed settles." The Ming dynasty artist Lan Ying's poem on his painting describes, "The clear frost comes at night, and the leaves of the old sweetgum turn red."

Among the most famous calligraphy pieces fitting for this season is Wang Xizhi's "Letter of Offering Oranges." Throughout various historical documents of calligraphy and painting, the depictions of late autumn landscapes are particularly detailed in Song dynasty works, creating scenes that leave lasting impressions, such as the Southern Song painting "Frost Sweetgum Mountain and Birds."

Frost's Descent Menu: Water Chestnuts, Osmanthus Sugar Lotus Roots, and Dunhuang Mushroom Soup

The "Collection of Explanatory Texts for the 72 Seasonal Terms" records: "In mid-September, the air becomes solemn and still, and dew turns to frost."

During Frost's Descent, seasonal food from Jiangnan—such as water chestnuts and arrowhead tubers—becomes available. Arrowhead tubers are often water-soaked and typically cooked in autumn. The Qing dynasty painter Jin Nong painted them multiple times, using rich ink, light ink, and fine outlines to depict four arrowhead tubers. The artwork is simple yet ethereal. The inscription reads: "Two slender ones emerge freshly from the water, without waves or wind disturbing the young lady. The evening sun is as usual, yet no sign of the arrowhead gatherers is seen. A small inscription from 'Qingjiang External History.'"

Jin Nong's painting of arrowhead tubers

People in Jiangnan have many ways to enjoy water chestnuts, which are crunchy and can be eaten raw, cooked, or in dishes. Foods made with osmanthus are also popular, such as osmanthus cakes, osmanthus wine, and osmanthus with bird's nest... During Frost's Descent, one must have osmanthus sugar lotus roots— a dish made with osmanthus, glutinous rice, and lotus roots, offering a rich taste.

Osmanthus sugar lotus roots

Persimmons also reach their most enticing state during Frost's Descent, with their skin firm and smooth, vibrant in color. A single bite releases the fruit's pulp like syrup, tasting as sweet as honey. A saying goes, "To supplement one’s body all year is not as good as in Frost's Descent." In Chinese culture, there are customs like “eating red persimmons,” “slow-cooking sheep's heads,” and “welcoming winter hare meat” during this season.

Persimmons in the Frost's Descent season

In ancient Dunhuang cuisine, it is not difficult to compose a "Frost's Descent Menu" for you to sample. Records of mushroom consumption in Dunhuang date back to the Tang dynasty. The Dunhuang document S.5927va mentions, "One measure of wheat, buy one measure of mushrooms," indicating that the Dunhuang people were well-acquainted with various ways to prepare mushrooms.

"Fresh fish abounds after the frost, flavors fill the streets." Whether fishing or enjoying fish, it's an excellent time for both. The Dunhuang document P.3468 "Drive Off the Nuo Spirits" states, "The stalks taller than an ox's waist, the turnips cheaper than horse tooth. No sign of hunger in people, flavors enhanced with fish. Everyone indulges in grapes, and in joy, no one is sober." Though somewhat exaggerated, the abundance of life and the joy it brings is surely something everyone can appreciate.

Cheese making in Mogao Caves, Cave 23. The strong cakes from the Tang dynasty once dominated the palates of ancient Dunhuang people, significantly influencing their diet.

As early as the Han dynasty, cakes were already present on Dunhuang's tables. In the Han bamboo slips unearthed in the Maquanyuan area of Dunhuang, there are records about cakes: "Greasy cake costing sixty per person." The Dunhuang documents also contain numerous descriptions of various types of cakes, totaling more than twenty kinds, nearly encompassing all members of the cake family.

Given it's deep autumn, beverages should also move towards medicinal soups. The Dunhuang people excel in brewing and enjoying wine. The wines embody the warmth and boldness of northern people, yet are not entirely coarse; there's subtleness to them. "He-li-le" (also written as "He-li-lu"), originally from Persia, is a medicinal herb used in brewing. Historically, it was held in the right hand of the Medicine Buddha, as stated in the "The King of Golden Light Sutra": "He-li-le contains six flavors; it can remove all diseases, a king among medicinal herbs." Combined with An-mo-le and Pi-li-le, it can brew an exotic sweet wine known as "San-le-jiang."

After Frost’s Descent, winter approaches even more closely. Besides the fallen leaves and changes in clothing, the knowledge within our meals also becomes a focal point.

Frost's Descent Calligraphy: Although many frosty colors are dyed, the ink marks remain deep.

Among the most well-known letters fitting the Frost's Descent season is Wang Xizhi's "Letter of Offering Oranges": "Offering 300 oranges; the frost hasn't descended yet, so we shouldn't gather too much." In essence, it conveys the message of offering 300 oranges, noting that it's still too early for harvesting because the frost has not yet come. This two-line arrangement is representative of Xizhi's cursive style. Although it mentions merely numbers, the strokes are rich in variety; some are angular, showing sharp edges, while others are rounded, understated yet substantial. The ink is vibrant, with a tranquil essence—each character stands tall, exhibiting a comfortable posture, revealing a style that is both straightforward and pure. Wang Xizhi also has another piece, "Frost's Cold Letter," which leaves a mark during this seasonal transition: "I, Xizhi, say: As frost and cold descend, may the holy body be cared for in accordance with the season. Unable to suppress my feelings, I sincerely express my actions and stillness. I, Xizhi, say." This is a greeting for the cold season, expressing concern for well-being with a few carefully chosen words.

Wang Xizhi's "Letter of Offering Oranges," Eastern Jin

Wang Xizhi's "Frost's Cold Letter," Eastern Jin

Yu Yue's calligraphy of Tang poet Zhang Ji's "Night Mooring by Maple Bridge," Qing dynasty

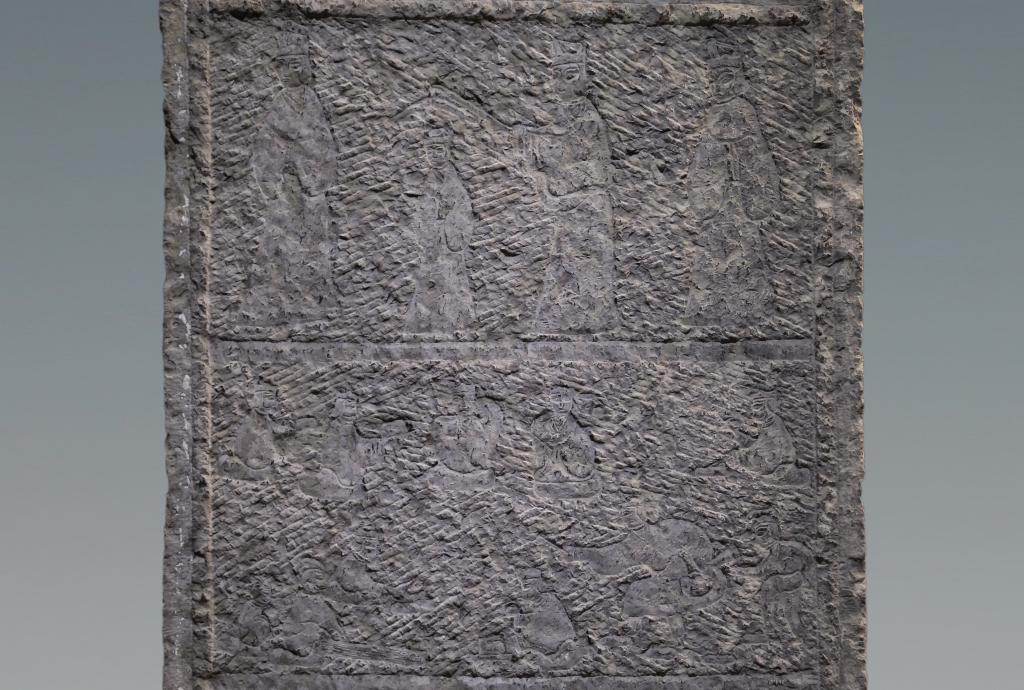

In poetry, there are many verses describing the frost’s appearance, and aside from Du Mu's "Mountain Walk," the most famous one is Zhang Ji's "Night Mooring by Maple Bridge": "The moon sets, and crows cry in a frosty sky, fishing lights next to the river meet my troubled sleep. Outside Suzhou city, there lies Hanshan Temple, at midnight the bell tolls reach the guest boat." Hanshan Temple has a stele inscribed with Zhang Ji's poem written by the Qing dynasty scholar Yu Yue, which has now become a famous attraction. The inscription states: "Hanshan Temple previously had the poem 'Night Mooring by Maple Bridge' written by the 文待诏 from the Tang dynasty, but with the passage of time, it faded. In the year of Gu Xu, the small stone minister refurbished several pillars in the temple and instructed me to re-carve the inscription."

Yu Yue's student, Wu Changshuo, repeatedly wrote this poem, with the example shown here written when he was eighty years old, revealing a sense of age in the brushwork. Besides emanating from the culture of stone drums, it also carries the charm of inscriptions.

Modern Wu Changshuo's calligraphy of Tang poet Zhang Ji's "Night Mooring by Maple Bridge"

Wu Changshuo, on "Frost's Descent," wrote the couplet "Not the same as a play," employing the seal script technique—a hallmark of traditional stone drum writing. For decades, Wu Changshuo dedicated himself to the study of the "Stone Drum Script," blending cursive and seal styles, presenting the polished and regulated script in a free and vigorous manner while encapsulating the essence of modern consciousness. This effort ultimately led to the formation of his distinctive style—powerful and refreshing, desolate yet thick, exuding ancient charm while brimming with spirit, creating an impressive artistic experience.

Frost's Descent Art Appreciation: In the center, red leaves bloom; at the corners, the green duckweed settles.

During Frost's Descent, the grass and trees begin to yellow, ushering in the "thousand trees swept into a sea of yellow" that defines late autumn. The Tang dynasty poet Bai Juyi wrote: "Clear and chilly, morning frost descends, a gentle breeze begins to stir. In the center, red leaves unfold, at the corners, green duckweed settles." The Tang poet Yuan Zhen also wrote, "Three weeks after Frost's Descent, one leaf of Chinese parasol is left."

In various historical masterpieces, the meticulous observations by Song dynasty painters in depicting late autumn scenes allow for a rich experience. For instance, Southern Song's "Frost Sweetgum Mountain and Birds" depicts a branch of a sweetgum tree, with sparsely scattered leaves slightly reddened from the frost. The abundant fruits hanging from the branches signify deep autumn. Three finches, each in different poses, perch upon the branches, with the branch boldly drawn in rich ink, while the veins and delicate twigs of the leaves are outlined in ochre color. The leaves and small fruits are rendered using the boneless painting technique. The detailed depiction captures the twisting backs of the leaves and the intricate angles of the branches.

"Frost Sweetgum Mountain and Birds," Southern Song, Collection of the Palace Museum

In this artwork, the finch is finely painted with a center-mounted brush to depict its feathers, while different parts of its body are delicately colored using white powder, ochre, and varying shades of ink. The composition is airy, blending stillness and movement, with vibrant colors that avoid garishness. This represents a meticulously crafted piece among Southern Song's small-scale paintings.

"Frosty Bamboo and Cold Chicks," Southern Song, Collection of the Palace Museum

The page of "Frosty Bamboo and Cold Chicks" from the Song dynasty depicts five fin