The mighty Yangtze River flows from the Tibetan Plateau, traversing high mountain gorges, crossing steep ridges and treacherous shoals, passing through the water towns of Jiangnan, and finally entering the sea at Shanghai, where it embraces all rivers, vast and magnificent. Culture is like water, quietly nourishing; civilization is like the tide, with the river’s roar resounding.

Pengpai News has collaborated with major media outlets from 13 provinces (regions and municipalities) along the Yangtze Economic Belt to launch the "Cultural China Tour | Song of the Yangtze" special project titled "Tracing Upstream." This series reports on cultural sites, museums, art galleries, landscape poetry, and intangible cultural heritage along the Yangtze River by tracing its course from the lower reaches upstream. This article is the first piece in the "Reflections on the River" series, featuring an octogenarian poet walking along the riverbank back to Chongming Island, where the Yangtze meets the sea.

Poster for the "Cultural China Tour | Song of the Yangtze" special project "Tracing Upstream"

As the car drives onto the more than ten-kilometer-long Shanghai Yangtze River Bridge, the vastness of heaven and earth unfolds— the muddy yellow river water spreads out before us, while the long bridge stretches like a dragon, extending far into the distance, where the faint green outline of Chongming Island is barely visible.

“When I was young, every time I saw the Yangtze, I would be moved to tears. My home is right by the northern tributary, and the sound of the Yangtze would often flow into my dreams, into my mat, and my pillow; it felt as if everything around me was the Yangtze River. Sometimes I could even hear the whistles of the riverboats…” said Xu Gang, the eighty-year-old poet, who then fell silent, gazing intently out the car window: the shimmering waves at the river’s end continuously flowing by.

However, this is not a feeling of homesickness, for just a minute or two later, the poet’s memories of the Yangtze and Chongming surge forth like a flood…the old poet spoke for seven or eight hours that day, to the extent that a few days later, when he encountered Brother Jianbang, who had been with him all along, he remarked, “The old man was probably too excited that day; after talking too much, he had to take medicine and caught a cold.”

This made me feel somewhat guilty. However, upon reflection, the responsibility likely does not lie with me but with the deep-rooted affection for his hometown within the poet, with the sound of the Yangtze.

Those who have a hometown to return to are indeed fortunate.

“I like Heidegger's quote: Going back to one’s hometown is the poet's duty.” Xu Gang said, “I once wrote in a book: ‘The blood running through my veins is the smallest tributary of the Yangtze River.’ Why? Because I grew up drinking the water of the Yangtze, and the cultural impact it had on me is profound, it is Chongming Island.”

Born in 1945, Xu Gang gained fame in his youth through poetry and prose. After graduating from Peking University, he returned to his hometown before being transferred to the Literature Department of People's Daily. In recent years, he has focused on biographical literature and ecological literature, and last year he revised and republished “The Yangtze Biography”—likely the first biography of the Yangtze River.

In connection with the “Nature Notes” exhibition at the Shanghai Library, Xu Gang returned to Shanghai a few days ago. The curator, Shi Jianbang, who is also a native of Chongming, referred to himself as “Gangsi” and arranged a homecoming journey for the octogenarian poet.

Aerial view of Chongming Island

Yangtze Waves

The first time I met the old poet was at Xie Gongchunyan’s home.

It was around 2020 when Xie Gongchunyan had just turned eighty. Unlike now, when he has a long beard and is often silent, during his birthday, he painted “A Tree on the Eighty,” a lively spirit burning brightly, he was energetic and did not rest unless he stirred up some events. That year, when we were preparing the “Gengzi Art Exhibition” together in Shanghai, he would not sleep until three or four in the morning. The exhibition, originally planned for ten participants, ended up being expanded to seventy or eighty, with artists, scholars, poets, writers, collectors… even the renowned Peking opera artist Shang Changrong was invited. It seemed he wanted to include everyone in his circle who could write or paint—Xu Gang happened to arrive in Shanghai just then, pulled straight from the train station to join him, and soon called me, Jianbang, and Tianyang over to mix ink and adjust colors, wasting time at the hotpot downstairs, chatting and discussing art.

Now, I can’t recall exactly what we painted or talked about. My most vivid memory of Xu Gang is his wild and unconstrained brushstrokes, his conspicuous bald head, and the disheveled white hair on both sides. He mentioned that when he was young, Ai Qing had advised him to comb his hair properly, but he paid it no mind, bursting into hearty laughter after finishing his words, full of liveliness.

This is certainly the style of a poet.

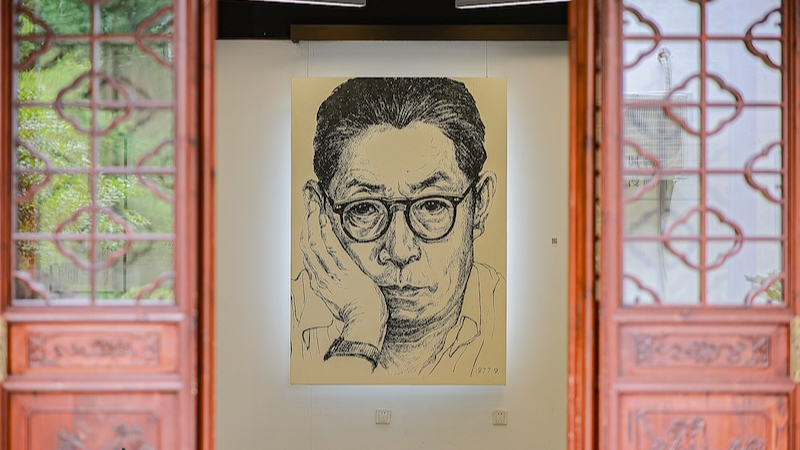

Sketch of Xu Gang by Gu Cun

Seeing Xu Gang again was during his homecoming for the “Nature Notes” exhibition. He lives near Fudan University and specially purchased a copy of his newly published “The Yangtze Biography.” Brother Jianbang, being attentive, brought along my art exhibition catalog from two years ago, “Village Words and Ink Intentions,” for him. As we flipped through it, I felt a bit ashamed.

After a bit of casual chat, the car head towards his dream hometown of Chongming.

Xu Gang embodies the vastness of the Yangtze River estuary, walking with long strides, as if he sounds like a chime, with his white hair fluttering in the breeze when walking along the riverbank, like reed fluff blown by the wind; his voice is robust, deep and resonant, which betrays no hint of an octogenarian's state.

He recalls the various events by the river from his childhood with utmost clarity, his eyes bright with youthful light.

Especially when he talks about the river water, the tones of his voice remind one of the sound of waves, evoking his character:

“It’s difficult to articulate how the sounds of the Yangtze tide would surge into the thatched hut every night, reaching my pillow, opening the mind of a mischievous child. What I can say for sure is that I would be astonished by it, filled with inexplicable excitement, and it raised many questions. It was this sound that brought me to the dike on the north bank of Chongming Island, which, for a child, felt towering and uneven. My friends and I would climb it, and the view ahead would be entirely different: a vast sky, the great river, surging bulrushes connected to the muddied waves of the Yangtze, along with boats and sails…”

Chongming, isolated in the heart of the river, frequently enduring floods, he recounted that in 1949, when he was five years old, a great flood occurred: “The flood kept pouring into our home, I was placed on the dining table while my mother and sister waded through the water to salvage belongings. We could catch fish in the house, and even pick up snails. The blood coursing through my veins is essentially the water of the Yangtze.”

His words evoke memories of my own childhood and hometown, reminding me of the floods in Yangzhou and other places in 1991. How similar it was! I recall my first encounter with the Yangtze as a boy taking a ferry from Yangzhou to Zhenjiang. The so-called "Jingkou and Guazhou are just a river apart," the rushing waters sliding eastward, making me feel an immense vastness of the world, leaving me nearly speechless; all I wanted was to stand quietly.

Since starting to write, Xu Gang has tried to reach out with his pen towards the Yangtze.

“The great river, the land, and my mother are inexhaustible sources of inspiration. I have traced upstream time and again, accumulating many details about the Yangtze in my heart. Until one autumn in 1995, I ventured to the protective forests of the middle and upper reaches of the Yangtze, and in 1998, I found myself in the vast wilderness of Qinghai Plateau, recalling the initial flux of the glacier under the snow-capped peaks of Jiali Dandong. Over the past decade, writing about environmental literature has led me to an unexpected realization: I’ve read many works on nature, geography, environment, and even philosophy, developing a closeness to geography and history. In my view, the trajectory of civilization has also become more concrete: always, one or several major rivers nurture a civilization; always, a region’s soil and water raises a group. The initial creators of civilization never consider they are creating civilization, but merely seek to reproduce and thrive, to have a place to call home. The sorrow of civilization reaching the present lies precisely in two aspects: on one hand, we still irreplaceably rely on geographic patterns and river currents; on the other hand, humanity's awe toward all this decreases, merely seeking to exploit and recklessly trample upon it.”

The Yangtze always stirs the heart, yet it also brings sorrow, thus it’s natural to speak of Mr. Huang Wanli and the various forms of pollution and destruction along the great rivers…

The poet laments that Chongming is perhaps the last sigh left by the Yangtze.

Chongming Academy and the First Grain of Sand

Upon arriving in Chongming, aside from the already operational Yangtze Bridge, a subway is under construction that will connect with Shanghai in two years—this could be the last district in Shanghai to have a subway connection. However, for the poet, there is a sense of loss, as he said, “The true Chongming Island is isolated overseas.”

The isolation from the rivers and seas, the relative safety brought on by the land-water separation, the tranquility far removed from the political and economic center, feels like a land akin to paradise; in the poet's eyes, this is the unique allure of Chongming Island—though perhaps it is merely the poet’s unfulfilled wish?

Nevertheless, the Chongming Academy, which houses the Chongming Museum, has preserved the island's “isolation overseas” and its historical memories.

Pond at Chongming Academy

Literature on Chongming's history at Chongming Academy

Founded during the Yuan Dynasty, Chongming Academy is currently the largest Confucian temple in the entire Shanghai area. The eastern and western archways, Lingxing Gate, pond, Dacheng Hall, and Chongsheng Shrine are arranged in an orderly manner, with many documents preserved about Chongming’s transition from sandbank to island. Zuo Zongtang, during his time as Governor-General of Jiangsu and Zhejiang, called Chongming the first line of defense for river protection, and even visited Chongming’s Shiyan Port to inspect the formation of fishing teams.

Nearby Chongsheng Shrine stands a stone tablet inscribed with “Memorial of Chongming Island’s Emergence” written by the poet over a decade ago, beginning with: “If viewed in the context of the great waves washing away the sand, then for 1400 years, as rivers and seas have surged, sands can be found at the ends of