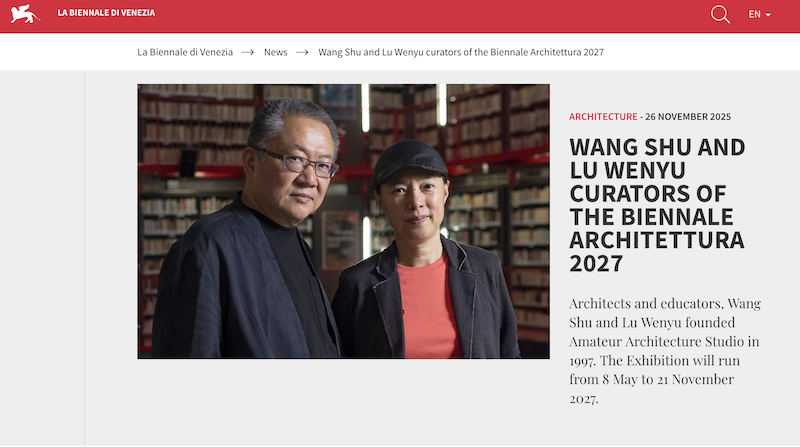

In the brilliant starry sky of the Renaissance, Leon Battista Alberti (February 14, 1404 - April 25, 1472) is one of the dazzling "generalists". He is an architect, architectural theorist, writer, poet, philosopher, cryptographer...

At the invitation of the World Art History Institute (WAI) of Shanghai International Studies University, Caspar Pearson, professor at the Warburg Institute of the University of London, came to China in the early autumn of 2024 to share his research on Alberti in the series of "Lectures of Outstanding Scholars in World Art History·Art and Culture in the Renaissance". He paid special attention to the time model in architecture and the relationship between architecture and images. The Paper exclusively interviewed Pearson. In his opinion, Alberti inherited a long tradition that highly values proportion and harmony. In this tradition, the beauty in a work of art or architecture comes from the relationship between the part and the whole. Architecture, sculpture, and painting are interconnected and competitive, and are one.

Caspar Pearson gave a lecture entitled "Architecture and Thinking: Alberti on Architecture and Urbanism" at the Liu Haisu Art Museum in Shanghai.

Caspar Pearson is a professor, dean of studies, and director of the Art History Program from 1300 to 1700 at the Warburg Institute of the University of London. His research focuses on the art and architecture of the Italian Renaissance, especially Alberti.

Pearson received his undergraduate and master's degrees at the University of Birmingham, and obtained his PhD at the University of Essex on architecture and urbanization in Alberti's works. He then lived in Rome for six years to conduct postdoctoral and related research. He returned to the University of Essex to teach in 2008. In 2011, he published the monograph Humanism and the urban world: Leon Battista Alberti and the Renaissance city. In 2020, Professor Pearson joined the Warburg Institute. In 2022, he published a new biography of Alberti, Leon Battista Alberti: the chameleon's eye, which belongs to the Renaissance Lives research series jointly planned by the Warburg Institute and REAKTION BOOKS.

Caspar Pearson, Humanism and Urban Culture: Alberti and the Renaissance City, 2011

Caspar Pearson's book Leon Battista Alberti: Eyes of the Chameleon, to be published in 2022

The title, “Eyes of the Chameleon,” comes from the humanist Cristoforo Landino (1424-1504), a Renaissance linguist and poet, who described his friend Alberti as “a new chameleon” who “always took on the color of what he wrote.” By comparing him to a chameleon, Landino wanted to convey that Alberti seemed to be constantly switching from one thing to another, with an astonishing range of activities. Similarly, the 19th-century historian Jacob Christoph Burckhardt (1818-1897) called him “uomo universale” (an Italian phrase meaning “generalist”), and he considered Alberti a man who could do everything.

Leon Battista Alberti, Self-Portrait, c. 1435, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. This is one of the few surviving images of this multi-talented Renaissance figure and is important for understanding Renaissance portraiture and the broader context of self-representation. In Alberti's time, portraiture was usually reserved for the upper classes, and Alberti's choice to present himself in this way highlights his self-conscious awareness of individualism and the image of the intellectual.

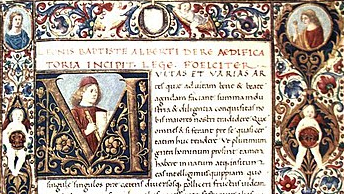

But Alberti's achievements in the field of architecture have received more attention. His On Architecture, published in 1485, was the first complete work on architectural theory at the time, and with the help of Gutenberg's printing press, it promoted the development of the Renaissance. Pearson's lecture in Shanghai, "Architecture and Thinking: Alberti on Architecture and Urbanization", also focused on his achievements in architecture, which is also the essence of his biography of Alberti - he tried to combine Alberti's texts, architectural works and images.

The conversation between The Paper and Caspar Pearson also revolves around the “generalist” Alberti.

Alberti's De re aedificatoria, completed in about 1452, proposed that "beauty consists in that harmony of parts which are so rationally arranged as to make the whole so much worse by any addition, subtraction, or alteration."

This book is a milestone work on architectural theory during the Renaissance, covering the design, function, technology and aesthetic principles of architecture, and is a combination of classical architectural tradition and humanistic thought.

Alberti and the Renaissance

The Paper: Your research focuses on Alberti. How did you become interested in him and conduct research on him?

Pearson: When I started my PhD, I wanted to write about the topic of architectural imagery in Italian Renaissance painting. To do this, I read some 15th-century primary sources, including Alberti's De re aedificatoria and De familia. My advisor suggested that I organize my thoughts by writing about these two works, and I found myself fascinated by Alberti's thought. His thought struck me as incredibly complex, rich, and multi-layered, and full of confusing and challenging elements. I quickly realized that this was the topic I really wanted to study. It was also a very interesting period in Alberti studies, and many new academic approaches began to emerge.

I was very lucky that while I was writing my thesis, Leon Battista Alberti: Master Builder of the Italian Renaissance, written by Anthony Grafton (born in 1950, former president of the American Historical Association, currently Henry Putnam Distinguished Professor at Princeton University, member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and corresponding member of the British Academy), was published. This important biography of Alberti has greatly promoted scholars' research in this field.

Anthony Grafton, Alberti: Master Builder of the Italian Renaissance, 2002

Anthony Grafton analyzes Alberti's works in art, architecture, and philosophy in detail in his book. He places Alberti in the broad intellectual context of the time. Before this, there was neither a major biography of Alberti nor a comprehensive study of his works in the English-speaking world. Although cultural historian Joan Kelly Gadol published Leon Battista Alberti: Universal Man of the Early Renaissance in 1969, its scope was limited and did not cover all of Alberti's areas. Through a broader academic perspective, Grafton shows that Alberti was not only an art and architectural theorist, but also a writer, philosopher, satirist, and an independent and sharp intellectual in a complex academic environment. He reveals the deep motivations and inter-textual complexity in Alberti's works, shaping Alberti into a more multifaceted humanist scholar.

The Alberti Portrait, attributed to Filippino Lippi, is located in the Brancacci Chapel as part of Lippi's work on Masaccio's The Raising of the Son of Theophilus and The Throne of St Peter.

The Paper: Although Alberti was considered a "generalist" and "all-rounder", Vasari emphasized Alberti's academic achievements rather than his artistic talent: "He spent time understanding the world and studying the proportions of antiquities; but most importantly, he followed his own talents and focused on writing rather than applied work." "In painting, Alberti did not achieve anything significant or beautiful." "His few extant paintings are far from perfect, but this is not surprising, as he was more focused on research than drawing." What do you think of Vasari's evaluation of Alberti?

Pearson: As you said, Vasari's evaluation of Alberti was not very positive. He emphasized that Alberti was a theorist rather than an artist, and he thought that Alberti's paintings were not of high quality. Today, we cannot judge this because no paintings of Alberti have survived. However, Alberti was not a professional painter, and he probably did not paint many paintings. However, we do not know whether the works Vasari saw were actually painted by Alberti.

I think Vasari was intentionally drawing an implicit line between himself and Alberti, emphasizing that his own expertise as an art critic was derived from his identity as an artist, and that Alberti, though he wrote, did not actually create, which meant that he could never achieve true understanding. This ambiguity has continued into modern times, for example in the work of Julius von Schlosser (Austrian art historian, 1866-1938), who does not describe Alberti as a non-artist and a dry theorist. However, while Schlosser belittled Alberti's architectural achievements, Vasari did not do so. In fact, Vasari's Lives of the Great Artists is the earliest extant document to attribute many important Florentine buildings to Alberti.

The Paper: During the Renaissance, many "generalists" were born. In your opinion, what are the concepts of "Renaissance" and "Renaissance man"? How to understand "Renaissance" from the perspective of architecture?

Pearson: There is no simple definition of the word "Renaissance." The word itself comes from the French and means "rebirth." It is generally thought to refer to the revival of certain elements of Greek and Roman ancient culture that began in Italy around 1400, although some scholars date it to earlier. Some believe that the Renaissance marked a complete historical period, while others see it as a loose movement in which only a relatively small number of people participated. Today, many people reject the term altogether, viewing it as an idea about history that is unfounded and unsustainable. There is much debate surrounding the topic, but no consensus.

From an architectural perspective, the Renaissance is traditionally considered a period of revival of ancient Greek and Roman architectural styles. During the late Middle Ages, Gothic architecture flourished in many parts of Western Europe, especially in large monumental buildings. The revolutionary feature of Gothic architecture was the construction of tall, light-filled buildings, best exemplified by the cathedrals of Bourges and Chartres in France. The most defining feature of Gothic architecture is the pointed arch, and other common features (in large buildings such as cathedrals) include flying buttresses, which help control the force of ceiling vaults (allowing architects to build buildings taller), spires, and large stained glass windows.

Facade of Bourges Cathedral

During the Renaissance, architectural styles shifted as architects, artists, and stonemasons drew inspiration from the many Roman ruins still standing in Italy and began to use classical elements found there, such as columns (or pilasters) and arches. Examples of this type of architecture include Brunelleschi's sacristy of San Lorenzo in Florence and Donato Bramante's (c. 1444-1514) Tempietto (literally "small temple") in Rome the following century.

Andrea Palladio included a woodcut depicting Bramante's design for the Tempietto in his book I Quattro Libri dell'Architettura (published in 1570).

Today we usually call this style "classical architecture", but during the Renaissance it was more commonly known as "all'antica" (ancient style). Alberti wrote and designed buildings in this style, and this fascination with the ancient world deeply influenced him and his contemporaries. However, the Renaissance style consciousness was not yet fully defined, and Alberti did not regard Gothic architecture as a separate style, nor did he criticize it. In the 15th century, people had no dogmatic sense of "style", and Gothic, Renaissance and other styles of buildings were built and coexisted at the same time.

The Pietà, located in the Galleria Bigallo in Florence, was created in the 14th century.

Detail of the "Pieta" showing a Florentine cityscape.

The idea of the “Renaissance man” derives from 19th-century discourse, which is also the period when the concept of the “Renaissance” was formed. For example, the French historian Jules Michelet (1798-1874) argued that a new type of person emerged during the Renaissance, who was bold, sober, rational and calculating, and completely different from the personality types of the Middle Ages. Similarly, the Swiss historian Jacob Burckhard (1818-1897) argued that the modern individual first emerged in the Renaissance, typified by figures like Alberti and Leonardo da Vinci, who were competent in everything and had the confidence to follow reason rather than authority and tradition. This constitutes what we call the “myth” of the Renaissance, which was developed in 19th-century historiography.

Leonardo da Vinci, Vitruvian Man, a study of how to fit the human body into two geometric shapes

The Paper: What is the significance of the 19th century’s construction of the Renaissance “myth” for modern society?

Pearson: This is a difficult question. Some people argue that the "myth of the Renaissance" has long been a key component of the Western view of history, and even now it remains so. In this framework, history is seen as a pattern of peaks and troughs on the one hand, and a gradual move toward progress and modernization on the other. The Renaissance is seen as both a "peak" of history and an important step toward modernity.

Philosopher Nietzsche saw the Renaissance as an example of “monumental history,” a mode of history that seeks to inspire contemporary action through grand narratives. But he believed such narratives simplified history and ignored complexity.

Modern scholars have criticized the Renaissance "myth", questioning its excessive focus on Western Europe, pointing out its relationship with colonial exploitation, and arguing that its concept originated from the specific concerns of scholars in the 19th and 20th centuries. From a historiographical perspective, the Renaissance has been used to belittle the Middle Ages and serve a specific historical narrative. Therefore, it is very important to look at the Renaissance critically and recognize the relevant historiographical debates.

The Paper: Alberti wrote On Painting at the beginning of the Italian Renaissance. His contemporaries included Donatello, Brunelleschi, Gilberti, and Masaccio. In the preface of On Painting, Alberti wrote that it was dedicated to his contemporary architect Filippo Brunelleschi and asked for his advice. What was the relationship between them? What was the influence of On Painting on later generations?

Pearson: In the summer of 1435, Alberti, who was living in Florence, finished his treatise on painting, On Painting. There were two versions of On Painting: one in Latin and one in Tuscan (a form of Italian). He sent a manuscript copy of the Tuscan version to Brunelleschi, along with a letter praising the architect's work on the dome of Florence Cathedral and mentioning a number of other artists.

Alberti, De pictura (Della pittura in Italian): first edition completed in 1435 (first printed edition published in Basel in 1540)

At the time of the letter, the Florentines were in the final stages of rebuilding the city's cathedral, a massive project that had begun in 1299. In particular, the builders had only a few months to complete the cathedral's magnificent dome, or cupola—an extraordinary structure that, at more than 45 meters in diameter, was too large to be built using conventional methods. Typically, a dome would be supported by a wooden stilt, a supporting scaffold that holds it in place until it is finished (as shown in the image below). But the cathedral's dome was so large in diameter, and the amount of wood required was too great to construct a proper stilt. So, Brunelleschi invented a method to build the dome without any supports, which seemed almost miraculous to many observers.

Vaulted roof constructed with wooden supports

The relationship between Alberti and Brunelleschi has been the subject of much speculation. Some have suggested that the lack of contact between Alberti and Brunelleschi, and the lack of a known reply from Brunelleschi, may indicate that the letter was not well received at the time. Others have suggested the opposite, that the letter indicates a constructive dialogue between the two men, and that Brunelleschi may well have provided comments and suggestions, as Alberti requested in the letter, which may have been incorporated into later versions of On Painting, which were indeed more complete. There is no definitive evidence for this. Regardless, the letter shows that Alberti was interested in the art and architecture of Florence at the time, and that he considered it to be of great significance.

Statue of Brunelleschi overlooking the dome he designed

The letter also suggests that, in Alberti’s mind, his appreciation of Florentine art was closely tied to his family and its return to Florence from what he called “a long exile.”

A possible portrait of Brunelleschi. Masaccio, The Throne of Saint Peter (1423-1428), Brancacci Chapel, Florence

In the long run, On Painting had a considerable influence. Although artists did not directly read the book and strictly follow its precepts, it laid the foundation for a tradition of Renaissance art theory that influenced artistic practice and understanding in many ways. Alberti systematized art for the past 130 years to a certain extent. He also gave the first written description of perspective, which was developed by several artists at the time and later more widely explored by artist-mathematicians such as Piero della Francesca. Some believe that Alberti's insistence on narrative and comprehensibility in art marked the beginning of a humanistic approach that eventually led to the iconography of the German scholar Erwin Panofsky (1892-1968).

Alberti's On Painting describes a perspective grid for precise placement of objects.

Piero della Francesca, The Resurrection of Christ, circa 1460s, fresco

The Paper: Did Alberti’s theory have any influence on the design of the dome of the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore?

Pearson: The dome of Santa Maria del Fiore was designed and built before Alberti began writing architectural theory, so his theory had no direct influence on it. However, Alberti had an important influence on the dome's later evaluation because he was one of the first scholars to comment on it. In the famous letter attached to "On Painting", Alberti highly praised the dome and Brunelleschi, saying that the latter not only achieved the achievements of ancient architects, but even surpassed them. Some scholars believe that this may be the key moment when Alberti became interested in architecture.

Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral

Sectional view of the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral

As for Brunelleschi’s collaborations with other artists, the construction of the cathedral and its dome was a highly collaborative effort. Although the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore is often referred to as “Brunelleschi’s dome,” he was actually just one of many players (albeit the most important one). Brunelleschi did not design the overall shape of the dome, but he designed some of the details and played a major role in solving the engineering challenges. He worked closely with others, including the sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti, to complete this engineering marvel.

Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore

Alberti and architectural theory

The Paper: Another more important work of Alberti is "On Architecture". What is the relationship between architecture, sculpture and painting in the Renaissance?

Pearson: Sometimes people say to me, "I'm only interested in Renaissance art, but I don't want to study Renaissance architecture." They may feel that architecture is too cold or separate from the other arts, but in the Renaissance, these fields were not separate at all. To truly fully understand the Renaissance, it is inevitable to know some architecture.

Tempietto designed by Bramante.

To see this, just think of the most famous architects of the Renaissance, the most iconic figures, most of whom came from the fields of painting and sculpture. There were no specific degrees or qualifications for architecture, the arts were intertwined. Brunelleschi, for example, was a goldsmith, but also a brilliant sculptor who created a number of important works. Alberti, the great theorist of architecture, also wrote about painting and perspective. In fact, he was a scholar and romantic who is often seen as the representative of the architect of the High Renaissance, and he began his career as a perspective painter. Michelangelo, of course, was one of the greatest architects of the Renaissance, but he was also a sculptor and painter.

Bonaccorso Ghiberti (son of Lorenzo Ghiberti), "Brunelleschi's Crane". This crane played an important role in Brunelleschi's construction of the dome of Florence Cathedral after 1446 and remains an iconic achievement of Renaissance architectural engineering.

These skills were theoretically closely linked. There is a lot of discussion in Renaissance theory about the relationship between architecture, sculpture, and the other sister arts, how they shared the same underlying principles, and sometimes how they competed with each other. But certainly throughout the Renaissance, there was a general belief that these art forms were linked to each other.

The Paper: Proportion and harmony play an important role in Alberti's architectural theory. How do you interpret his understanding of these concepts? What influence did ancient works have on Alberti? What special significance did they have in the social context of the time?

Pearson: Alberti was part of a long tradition that placed great emphasis on proportion and harmony. This tradition dates back to antiquity and was still influential in the Middle Ages. In this tradition, beauty in a work of art or architecture derives from the relationship between the parts and the whole, all presented in a coherent composition. In ancient architecture, proportion was key to ensuring that the parts were unified into a whole according to an understandable principle. Alberti also argued that the proportions used by architects were derived from nature, and that the harmony that architects sought was widely found in nature. Alberti was therefore able to point to nature as the source of his principles and claim that his theories were not arbitrary or accidental, but universal and always valid.

The new facade of the Cathedral of Rimini was designed by Alberti in 1453 and is one of the representatives of Renaissance architecture. Originally a Gothic church, it was transformed by Alberti and incorporated ancient Roman architectural style, especially classical columns and arches, marking the transition from medieval style to Renaissance style. This building not only has religious significance, but also reflects the combination of religion and civic life during the Renaissance.

Take the Cathedral of Rimini, commonly known as the Malatesta, for example. Alberti transformed the medieval Gothic Basilica di San Francesco into a new and amazing building. Alberti was brought in to redesign the exterior, starting around 1453. Although the building was never completed, a bronze medal made to commemorate it gives a glimpse of how Alberti intended it to be designed.

Obverse: Portrait of Malatesta; Verso: Design for the Church of San Francesco In Alberti's first major architectural project, we see him exploring many of the same themes that appear in the dome of Florence Cathedral in his letters to Brunelleschi.

First, Alberti took great pains to put the architecture of his time into dialogue with that of ancient Rome. The building's exterior, with its white stone and colored marble, recalls the temples of antiquity, with columns below and moldings above that echo a triangular pediment.

The Temple of Portunus (1st century BC) is one of the best preserved temples in Rome. It is dedicated to Portunus, the god of ports. It combines Etruscan-Campanian style with Greek elements. Alberti incorporated elements of the temple when he remodeled the cathedral in Rimini.

At the east end, there would have been a large hemispherical dome, which might remind us of one of the most famous ancient buildings in Rome: the hemispherical dome of the Pantheon. Alberti frequently appropriated other ancient buildings, imitating the most famous Roman monument in Rimini, an arch built in honor of the Emperor Augustus. On the sides of the cathedral, Alberti also mentioned the pier walls of the Colosseum.

The Arch of Augustus is located in Rimini, Italy. It was built in 27 BC to celebrate Emperor Augustus' conquest of Gaul and consolidate the peace of the Roman Empire. It uses classical architectural elements, symbolizing the power of the empire and Augustus' military success, and is an important symbol of the early history of the Roman Empire. Alberti incorporated elements of the Arch of Augustus when he renovated the Cathedral of Rimini.

The façade, meanwhile, presents a tripartite division—divided into three sections, with the central section being wider—that might remind us of the triumphal arches built in ancient Rome to commemorate the emperor’s military victories. Some of the colored stones Alberti used, such as purple porphyry and green serpentine, not only imitate ancient architecture, they were actually taken from it, removed from ancient buildings in nearby Ravenna. They are examples of what we call spolia—materials taken from one structure and reused in another, sometimes for purely practical purposes, sometimes because they were prized for their antiquity or prestige.

The Arch of Constantine was built in 315 AD to commemorate Constantine's victory over Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. The arch marks an important moment in Roman history, reflecting Constantine's power and the rise of Christianity under his rule.

The Arch of Septimius Severus was built in 203 AD in Rome.

He did not simply imitate an ancient building, but created a building that was both hybrid and complex in time. The formal organization of the building's exterior pointed to a kind of permanence - the permanence of strong formal relationships such as symmetry and mathematical proportion. This can be felt in a letter Alberti wrote to Mateo de' Pasti, who was then supervising the construction of the Cathedral in Rimini. In this letter, Alberti compared the proportional relationships of the facade to harmonious relationships in music, warning the builders that if they changed any of the measurements, it would cause disharmony and destroy the entire composition: a composition that was assumed to be perfect and eternal.

Letter from Alberti to Matteo de' Pasti In the letter, Alberti also made hand-drawn sketches for the facade, although he eventually chose another design.

Although Alberti does not explicitly state this, these discussions can easily be linked to social and political discussions of the time, in which the idea of a natural order and hierarchy needing to be maintained was sometimes raised.

The Paper: How did Alberti’s architectural ideas influence urban development during the Renaissance? Your research involves the relationship between architecture and power. What role did Alberti’s ideas play in the expression and management of power?

Pearson: Alberti's architectural treatise is a completely new and unprecedented work, and its nature is completely different from the ancient treatise of the Roman architect Vitruvius. Architectural historian Françoise Choay (born in 1925, French architectural and urban historian and theorist) believes that Alberti, unlike Vitruvius, did not tell readers how to build a set of normative buildings. Instead, he tried to provide generative rules for the entire field of architecture, thus opening up the discussion of modern urbanism.

Cover of the first English translation of On Architecture. Translated by Giacomo Leoni. The book is bilingual, with the Italian version on the left and the English version on the right.

Alberti is sometimes seen as a kind of early "Machiavellian" figure , in that his discussion of city-state governance was concerned not only with questions of moral good and evil. He considered what actions rulers, whether good or bad, could take. In any case, Alberti clearly realized that writing about cities and architecture was also about politics and the exercise of power.

Pienza is a town in the province of Siena in the Tuscany region of central Italy, adjacent to Montalcino. It is known as the "touchstone of Renaissance urban life". In 1996, it was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

Perhaps the most famous example of Renaissance urban planning is Pienza in Tuscany. The site was originally a small hilltop agricultural village called Corsignano. But it was also the birthplace of Enea Silvio Piccolomini, who later became Pope Pius II. When Pius II became pope, he decided to rebuild the village, turning it into a small city with a cathedral, a grand papal palace, and other monumental buildings. Overlooking the Tuscan countryside, Pienza is picturesque and has some important examples of Renaissance architecture. Scholars have suggested that Alberti may have been involved in the design, but there is no hard evidence to support this. Pienza is a remarkable place and well worth a visit!

Pienza scenery

The Paper: To what extent do you think the revival of classical architecture during the Renaissance has influenced the theory and practice of modern architecture? In contemporary Renaissance studies, how do you view the view that architecture is not only a historical legacy but also an active social and cultural practice?

Pearson: The Renaissance tradition of treatise writing, begun by Alberti, established the idea of architecture as an independent discipline with a distinct way of reasoning. This had a profound influence on the development of architecture, all the way up to 20th century modernism. The Renaissance revival of classicism laid the foundation for architects to take a confrontational stance, contrasting their built forms with the overall context of the city. Classicism still exists today in various forms, whether as conservative anti-modernism, postmodern pastiche or parody, or otherwise.

Alberti, Momus, 1440s-1450s Momus is a Greek god of satire or criticism, symbolizing criticism and satire. He is known for constantly finding faults in gods and humans. During the Renaissance, "Momus" was used as a symbolic title for literary works, usually expressing criticism and satire of society, culture or politics.

In contemporary Renaissance studies, architectural historians tend to approach Renaissance buildings and writings in a historical way, focusing primarily on their relationship to historical contexts and architectural traditions. However, many contemporary architects are interested in the Renaissance beyond its historical significance, and see it as having important implications for architecture and urbanism today. For these practitioners, the Renaissance can be an important starting point for creating new work, becoming part of a vibrant social and cultural practice, as you say.

Take the British architect and Pritzker Architecture Prize winner Richard Rogers (1933-2021) as an example. He was born and spent his early years in Florence, and has been in dialogue with the legacy of the Renaissance all his life. This is not a kind of imitation (Rogers is an innovative high-tech architectural designer and a visionary urban planner), but he believes that the humanism of the Renaissance and its cultural and technological innovations can still provide important references for the present. Therefore, when Rogers thinks about the urban development of Britain in the 21st century, Florence, Pienza and other places during the Renaissance are still his important reference models.

Completed in 1977, the Centre Pompidou, designed by Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano, transcends the concept of a mere building to become an outstanding example of modern architecture in the heart of Paris.

The Paper: Most of the Renaissance scholars who came to China this time conducted research from the perspective of artists' paintings and images. Alberti was more like a scholar with works and texts available for research. In your opinion, the emphasis and research angles of texts and images are different.

Pearson: I think that as scholars of Renaissance art and architecture we should approach the subject matter and materials we study as openly and unrestrictedly as possible. So painting, sculpture, architecture, material culture, and the texts associated with art should all be potential subjects of study. Of course, there are some fundamental differences between text and image, and certain methods of study may be more applicable to one material than the other. Text and image do operate in some very different ways, and we should not try to smooth over these differences.

In art history, the image always takes precedence because it is the discipline’s special domain (in contrast to the study of texts, which it shares with many other disciplines and which is central to literary studies). But ultimately, whether we are studying texts, images, or architecture, we are involved in processes of meaning and interpretation.

Note: Thanks to Lu Jia (PhD candidate at WAI), Wang Lianming (Associate Professor of Chinese and History, City University of Hong Kong), and the World Art History Institute (WAI) of Shanghai International Studies University for their great assistance in this article. The "Lectures of World Art History Distinguished Scholars" will start in September 2023. The theme of 2023-2024 is "Art and Culture in the Renaissance". The event has now ended. 12 top scholars from six countries were invited to China to share their research results in this field. There is one more person left in the "Dialogue with the Renaissance" series of interviews.