In the history of art, Siena, a small city in Tuscany, Italy, is often overshadowed by the brilliance of its rival Florence. However, the exhibition "Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300-1350" currently being held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York shows how this city opened up the possibilities of the Renaissance through exotic and rich colors. This exhibition is not only a tribute to Siena's artistic achievements, but also a profound journey to explore how painting has evolved from a skill to an art form.

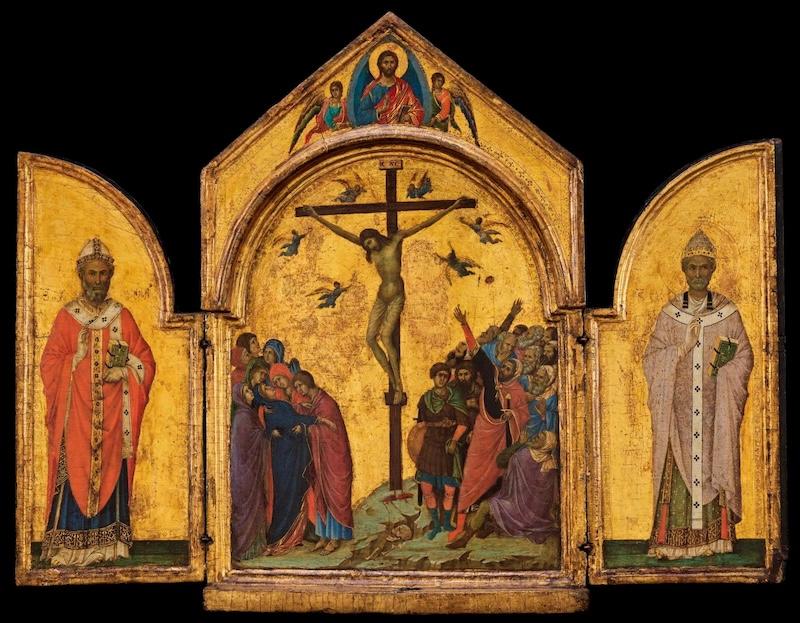

From gilded altarpieces to the invention of tempera paint, Sienese artists transformed painting from a religious tool into a medium for expressing emotion and exploring humanity in a brief but brilliant period. The exhibition includes works by Duccio (c. 1255-1319), Pietro Lorenzetti (1280-1348), Ambrogio Lorenzetti (1290-1348), and Simone Martini (1284-1344), focusing on the development of narrative altarpieces and the spread of the style beyond Italy.

Exhibition site

Cut down a poplar tree and whittle it into thin boards. Next, apply a barrier of gesso and animal glue to the thin board and, once dry, sand the surface. Repeat the process until you have a perfectly smooth canvas. Outline with a stick of charcoal, fill in the negative space with a gluey red mixture, then cover with a layer of translucent gold leaf (without glue, the metal takes on an unpleasant green hue) and polish with wolf's tooth. Now, and only now—you can pick up a paintbrush.

“Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300-1350” makes clear the astonishing developments that followed: painting became the center of Western art. Gold leaf was prettier, wood was stronger, and textiles and ivory (all of which are excellent in this exhibition) could be transported from city to city more easily than painted panels. No one would look at an egg yolk (the key ingredient in tempera) and think “sublime,” let alone “eternal.” Yet seven hundred years later, these paintings still survive, and even though we can no longer fully appreciate the shock of fourteenth-century perspective, they still strike the heart.

This was the power of Duccio di Buoninsegna, the most famous and influential painter in the show, who may well have employed several of the other greats in the show: Simone Martini and the brothers Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti.

Duccio, The Stocletian Madonna, circa 1290–1300

The exhibition opens and closes with two jewel-like paintings that clearly define the exhibition’s geographical and chronological scope. In the Stocletian Madonna (c. 1290–1300), Duccio depicts a tender Madonna and Child in precious pigments on a small poplar panel covered in gold leaf. Drawing on the traditions of Byzantine iconography and French ivory carving, he reimagines the subject as a moment of tender interaction between mother and child.

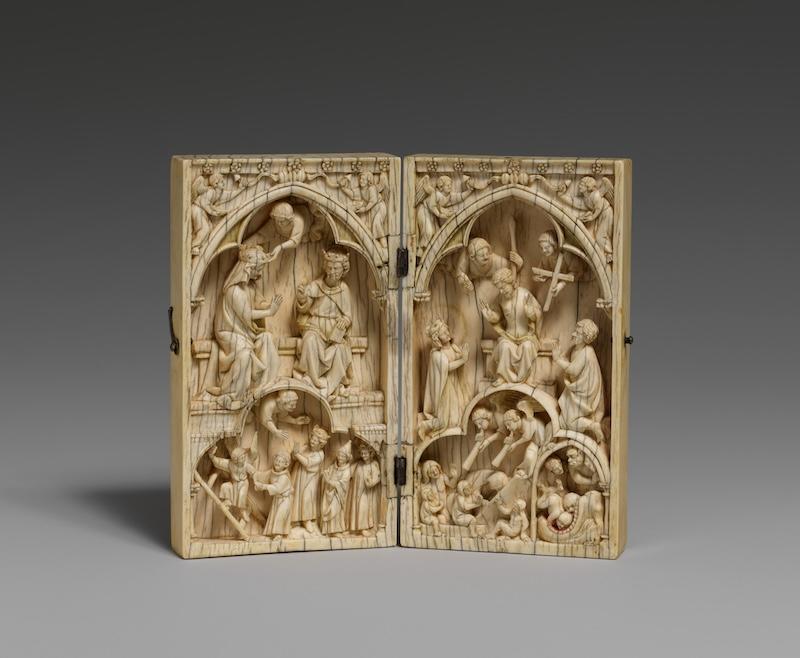

Coronation of the Virgin and the Last Judgement, France, circa 1260–1270 Designed for its owner’s private meditation and prayer, this palm-sized ivory diptych depicts the Coronation of the Virgin on the left and Christ and angels on the right. These scenes are drawn from contemporary architectural sculpture and are set within a series of arcades with trefoil pointed arches.

More than 40 years later, Simone Martini, the most radical painter of the post-Duccio generation, redefined this mother-son relationship in his painting Christ Found in the Temple, created in Avignon. In this work, the Virgin Mary and Joseph reproach Jesus for being lost in Jerusalem, their gestures clearly visible against the golden background. The 12-year-old Jesus responds with his arms folded, unmoved. Their figures are framed by a fine decorative frame. The mother who once held her child in her arms now confides in him across an unbridgeable distance, while he has embarked on a journey towards independence.

The exhibition, jointly curated by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the National Gallery in London, brings together more than 100 paintings, ivory products, textiles, sculptures, manuscripts and precious metal crafts to trace the glorious course of Siena's painting innovation in the first half of the 14th century. It is currently on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York until the end of January, and will be on display at the National Gallery in London from March 8.

In Christ on the Cross (c. 1311-1318), a tempera panel, note how Duccio shows the ordinary, real pull of gravity. Later Renaissance masters were more familiar with its effects on the human body, but no one could better depict this cold, unconscious pull, or suggest the hidden effort involved in the act of standing. In the lower left corner, a group of women support the staggering Maria, just as she wants to hug her son. One of the women's faces is slightly curved, as if she is smiling comfortingly, but that smile could also be seen as a Munch-like scream. Almost smiling, almost standing - the deepest emotions are contained in the simplest things, slightly misplaced, but real in broad daylight. The Sienese school knew how to be sad.

Duccio, "Christ on the Cross; Savior and Angels; St. Nicholas; St. Clement", circa 1311-1318, is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. As one of the museum's important early Italian Renaissance works, it demonstrates Duccio's status and influence in art history.

The Sienese also understood victory—at least for a while. As painting was eclipsing other art forms, Siena itself was trying to rise, albeit with mixed results. Its rival, Florence, had rivers and superior natural resources, and prevailed in a crucial battle in 1269. Siena’s secret weapon was its location on the Via Francigena, a pilgrimage route linking Rome to Canterbury. Islamic carpets, French sculpture, and scholastic scholarship flowed in, leaving behind a style that was both overly decorative and bluntly mysterious.

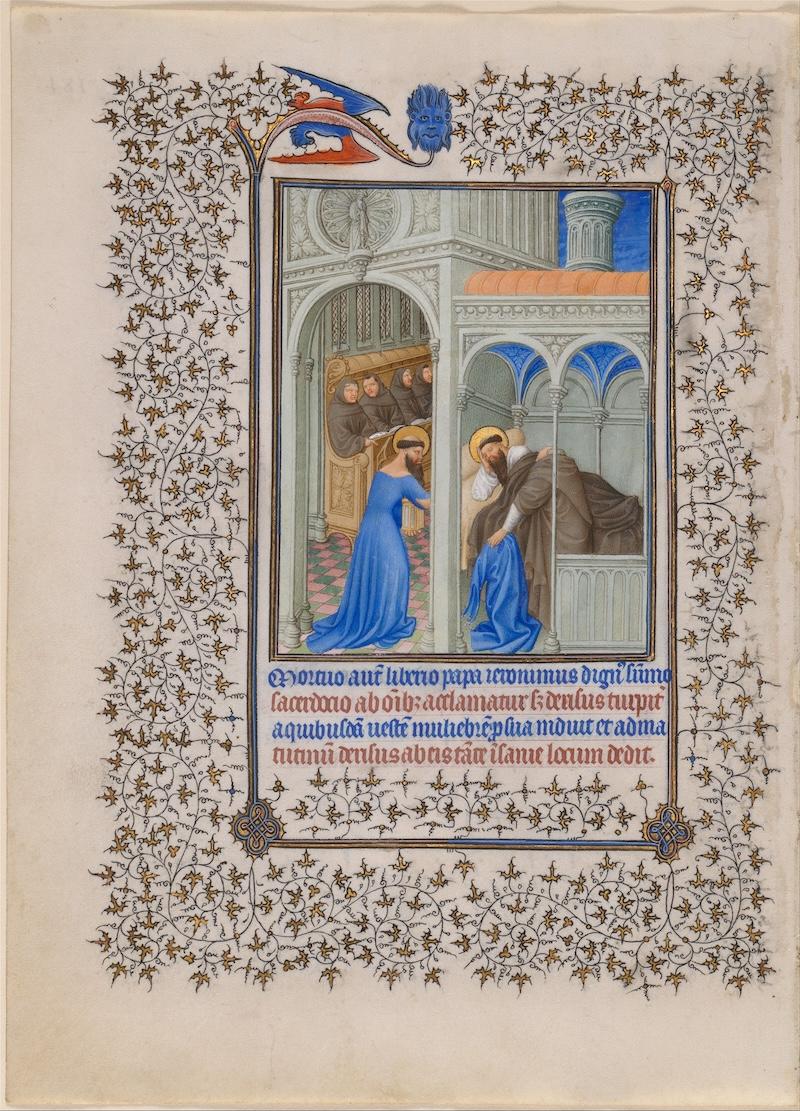

Limbourg Brothers, Prayer Book of Good Times, 1405–1408/1409

This prayer book, probably created in Paris, was a private prayer book and is one of the most luxurious manuscripts from the Middle Ages that has survived to this day. It was commissioned by the Duke of Berry in France to the Limbourg Brothers, the most talented artists of their time. It is the only complete manuscript work by the Limbourg brothers.

The exhibition weaves a series of thematic groupings into its temporal narrative, covering Siena’s role as a commercial center on an important trade route, beginning with a 13th-century Byzantine icon and its jewel-encrusted gold covering in the exhibition’s first room, to textiles from Central Asia, Iran, Anatolia, the Iberian Peninsula, and Italy displayed throughout the exhibition. These rich media refocus our attention on paintings, no longer as isolated images or transparent windows, but as material objects that really exist in the world.

14th century fabric. This piece of fabric displays bands of different patterns, conveying wishes for happiness, good luck and prosperity. The contrasting red, green and gold colours are typical of the fabric styles of the Nasrid dynasty and its later period in Spain and North Africa.

By the end of the 13th century, paintings had become one of the main exports of the city. Duccio was commissioned to paint an altarpiece for the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence. Pietro painted in Assisi, Cortona and Arezzo, and Simone Martini was summoned to the Papal Court in Avignon. But the gods seemed to play a cruel joke. In the 1340s, Simone Martini died (Duccio was long gone) and the Black Death swept through Siena. By the time the plague subsided, the Lorenzetti brothers were dead, and with them half of Siena's population.

The doom was only the beginning. Even as Siena recovered, Florence’s rising prominence in art and politics meant that Florentine artists produced the most art and wrote almost all of history. In his 1550 Lives of the Artists, Vasari insisted that Duccio’s altarpiece for the church of Santa Maria Novella was actually by the Florentine painter Cimabue. (Vasari did praise Ambrogio and Pietro, but failed to note that they were brothers.) With the rise of realism, it was easy to see the Sienese school as a door to a higher art, rather than an end point.

When changing tastes in art revived the early Renaissance in the late 19th century, even critics could not hide their irony in praising Sienese painting. The English writer Vernon Lee believed that the Sienese school had a refined charm, but this charm was "the charm of still waters", and its "beauty of color" was rooted in an inherent "naivety".

Segna di Buonaventura (1298-1326), Madonna and Child with Nine Angels, circa 1315

This exhibition offers a new perspective on Siena’s importance, presenting its protagonists through its most revolutionary masterpieces, including valuable loans and a rare reunion of polyptychs that were scattered in major collections in Europe and the United States. Of particular interest are the eight surviving panels from the back plinth of Duccio’s altarpiece for Siena Cathedral, a masterpiece of ingenious visual narrative reunited for the first time in hundreds of years.

The Sienese painters were as inventive as anyone, past or present, in all aspects—angels (cosmic messengers, unlovely), silhouettes (note the architectural curvature of the Virgin’s body in several Annunciation scenes), earth (sometimes fragile, sometimes lushly compressed), and tiny (some of the finest paintings in the show are less than a foot high and sparsely lit, yet appear large and bright).

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, The Annunciation, 1344, National Gallery of Siena, demonstrates Lorenzetti’s masterful control of space, light, and narrative detail.

Many of the artists in the show excel at depicting architecture, but Pietro takes the cake with scenes like The Trial of Christ, where arches and columns surround Jesus. Beyond that, you get whole city shots. The pretty little cities in The Trial of Christ give the impression of people trudging through their daily lives, unaware that at any moment they could be trampled down by a giant devil above them. Siena also captures the dramatic irony accurately.

Bohemian painter, Madonna and Child on the Throne, c. 1345–1350

The exhibition features the Maestà, whose dozens of small scenes are now disassembled and scattered in collections or lost. Duccio created it with the help of many skilled craftsmen, and the exhibition blurs the line between artist and craftsman.

Duccio, The Raising of Lazarus, c. 1310-1311, Kimbell Art Museum

Duccio is at his most restrained, finding some strange spaces in Christian iconography. That’s why it’s so important to see parts of the Maestà reassembled: you can sense the subtle gaps the artists played with one another. Ambrogio’s Christ on the Cross (c. 1345) shares many elements with Duccio’s version, but he pushes the image of a broken, unbalanced Maria to the extreme, until she almost collapses in the dust, while maintaining an atmosphere so subdued it’s almost unbearable. Restraint is not the same as blandness.

Lippo Memmi, Madonna with Saints and Angels, Italy, circa 1350. This panel, intended for private prayer, was part of a diptych that also included a panel depicting the Passion of Christ, now in the Louvre in Paris.

Centuries of prejudice against Siena have failed to obscure the fact that Ambrogio should be better known than he is. His Nursing Madonna (c. 1325) unwittingly attempts the impossible, and succeeds. The infant in the Madonna’s arms appears both heavy and light as air; his chubby left leg interacts with the fluttering pink fabric to create a sense of both movement and a palpable droop. Paradoxes like these give the painting a hypnotic strangeness. But the Sienese painters were too bothered to smooth over these contradictions; they reveled in their paradoxes. So Vernon Lee was not wrong to see a certain childishness in their paintings; it’s just that childishness, a complete disregard for either/or choices, is probably the most subtle thing about the painting. But the Sienese school did not always handle the human face well. It was a shortcoming, but not necessarily a flaw. Consider that this may have prompted Duccio and his followers to compensate through expressive line and color.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, The Breastfeeding Madonna, c. 1325

Together, the exhibition and accompanying publication form a framework that provokes new questions, encouraging us to explore individual works while tracing broader artistic patterns of the period. Yet this framework itself deserves further questioning and expansion. Neither the exhibition nor the publication explores Siena’s relationships with other European artistic centres, particularly the Neapolitan court. The Metropolitan Museum of Art hints at these connections with its recent acquisition of a Bohemian Madonna and Child, and the National Gallery’s exhibition is expected to make similar additions with its Wilton Diptych. But perhaps we should think of Sienese painting not simply as radiating out to Europe via Avignon, but rather as part of a constellation of interconnected centres, and trace the rise of painting within these complex cultural relationships.

Simone Martini, The Discovery of Jesus in the Temple, 1342

The three faces in Simone Martini’s The Foundling of Christ in the Temple (1342), at the exhibition’s end, have none of the typical Sienese dullness. Joseph glares at his teenage son, Maria tries to hide her pain; the Saviour himself glares like an urchin who has broken curfew. It’s certainly extraordinary, and as the wall text suggests, its exquisite liveliness “marks a new era of independent painting in Western art”, which becomes the exhibition’s ultimate thesis – that Sienese painting from the first half of the 14th century had a profound influence on European art right up to the modern period. Yet, as this fascinating exhibition shows, even when relying entirely on its own language, Sienese painting was conceptually radical, formally experimental and deeply humanistic.

Siena in Tuscany, Italy

Note: The exhibition will be on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York until January 26, 2025; the exhibition at the National Gallery in London will be from March 8 to June 22. This article is translated from "The City Where Painting Became Art" by The New Yorker (by Jackson Arn) and "The Sienese Painter Who Ignited the European Art Revolution" by Apollo Magazine (by Sarah K. Kozlowski)