From a letter from Joan of Arc to the works of Christina de Pizan, the first professional female writer in Europe, the British Library's special exhibition "Medieval Women: In Their Own Words" recently showed the public the stories of women from 1100 to 1500. The exhibition presents more than 140 exhibits, including paintings, manuscripts, documents, early printed books and daily necessities, telling the lives of medieval women and revealing their wisdom, artistic talent and struggles.

What does hell smell like? At the British Library, when you open a small wooden door, you breathe in a bitter, herbal odor. It's the smell of sulfur, and the smell of a long-sitting breakfast plate. You'll be there. Close the door before the devil shows up, and open another door next to it, and you'll smell the sweet smell of honey. The British Library has gone to great lengths to encourage people to travel through time and space.

The horrible smell in the exhibition is inspired by the 16th and final vision of Saint Julian of Norwich, in which she claimed to have encountered a very strange old demon. The nicer, sugarier smell is meant to evoke the mystic Margery Kempe's "marriage" to Christ. Angels are apparently aromatic and pleasant. Visitors can smell both scents in the special exhibition's Spiritual Life section. Among other exhibits, the two scents are placed together with Cleopatra's manuscript Ancrene Wisse, a guide written by a priest in the early 13th century for three sisters who wanted to become nuns.

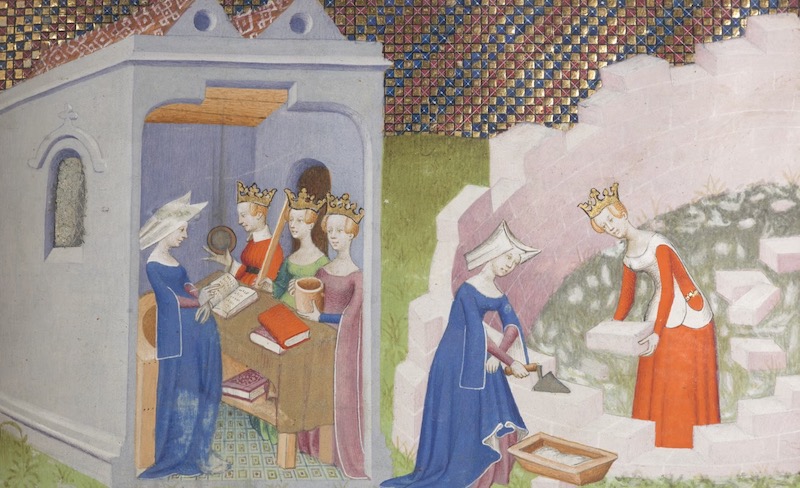

Illustration from The Book of the City of Ladies by Christine de Pizan, circa 1405

Of course, the nuns chose to be confined to a church cell in order to devote themselves to the contemplation of God. The strict rules on pets (one cat is allowed) and personal interior life in Ancrene Wisse, shown here, give the British Library exhibition a better sense of the olfactory experience than it offers. Even more wonderful, this is more of an ascetic exhibition than a sensory one. In the dark, semi-lit rooms, you find strange things that are uncanny. You feel like you have taken a cold shower and then you are refreshed.

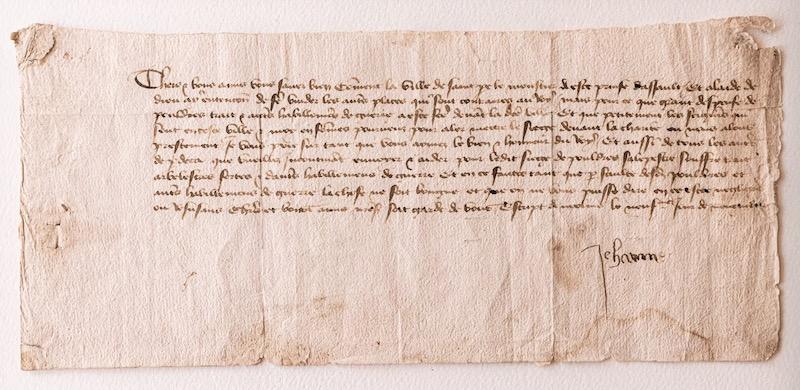

Letter from Joan of Arc to the citizens of Riom, November 9, 1429.

The exhibition covers European stories from 1100 to 1500, including a letter from Joan of Arc to the citizens of Riom, whose help she needed to lay siege to Charité-sur-Loire. It should be noted that the letter was dictated, as Joan could not read, but it was signed by herself. It is also the earliest of only three letters that exist. Among several lively letters written by the Paston family of Norfolk between 1402 and 1509, one, sent by Margery Brews to her fiancé John Paston III in February 1477, is the oldest surviving Valentine’s Day letter in English. There is also a copy of The Book of the Queen by Christine de Pizan, a Venetian writer at the French court, who is often considered the first professional female writer. This glittering collection of 30 of her works, produced for Isabella of Bavaria, Queen of France, features de Pizan kneeling in a lapis lazuli blue dress to present the book to the queen.

Colored cover of the Book of the Queen (c. 1410). Christine de Pisan presented her manuscript to Isabella of Bavaria, Queen of France.

It is, of course, a thrill to see Margaret Paston in person. This is no reprint of an Oxford classic paperback. There is a sense of familiarity, a golden thread that bridges centuries. While the notes are often gossipy, don’t be fooled into thinking the author’s concerns are any different from ours today. After all, in 1448 Paston wrote to her husband John asking for “crossbows, arrows, axes, and armour for the servants” because their estate had been taken by the enemy. Strangeness is everywhere in the exhibition, and these are things that would have been commonplace for those who lived through them, but are completely foreign to today’s audience.

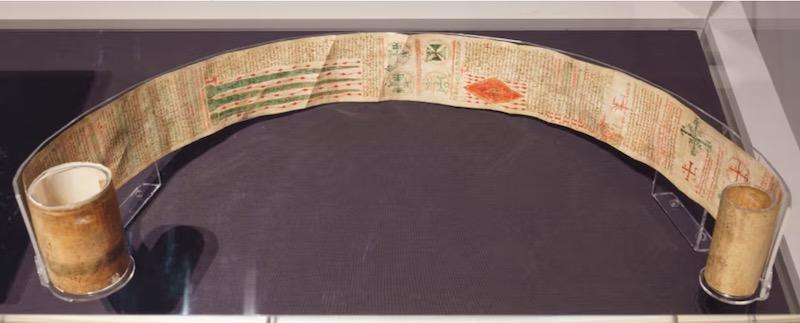

In the section devoted to childbirth, for example, there is not only a 14th-century Latin translation of an 11th-century Arabic treatise, complete with grisly gynecological tools, but also an early 15th-century parchment birthing belt, covered with prayers and charms, intended to protect women during childbirth. Also included is a life-size image of Christ’s wound on his side, through which, according to medieval interpretations, Christ created the church.

England. Birthing belt, early 15th century

Exhibits like these blend faith and superstition, making the curators’ occasional references to sex workers and the gender pay gap seem bland and perverse. Thankfully, the curatorial team doesn’t explicitly cast women as feminist heroes. Female power in this period was largely allocated to queens, including Matilda of England, Isabella of France, and Elizabeth Woodville, the wife of Edward IV, and abbess convents, who could read, build new chapels, and boss other women around.

Portrait of Margaret of York

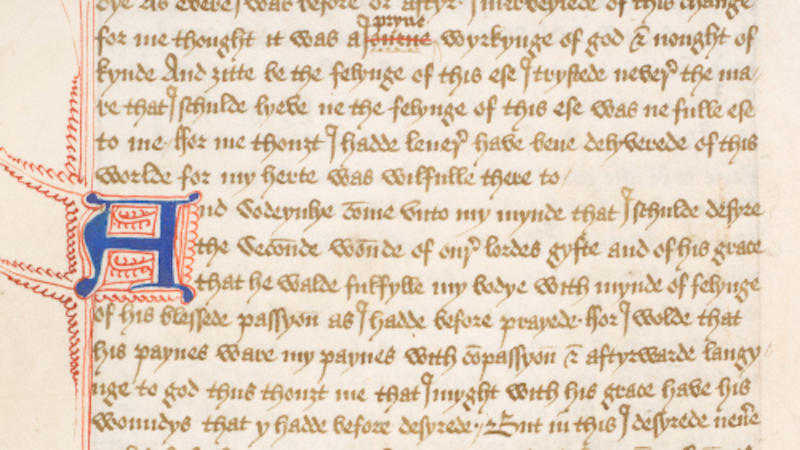

How to breathe? How to move through the world? If the mystical tendencies of the era were rooted in a deep and pervasive faith, they were also a license from God to be transformed, a divine excuse for a certain outrageous behavior. Margery Kemp was always crying in public, and the more embarrassed people were about it, the more she seemed to enjoy it. In the exhibition, visitors are able to learn about The Book of Margery Kemp, which is generally considered to be the first autobiography in English, dictated to a "reluctant" priest. Of course, one would imagine that even if the priest wanted to argue with Kemp, he would not dare to argue with God.

Italy. Ivory comb, circa 1360-1380

This exhibition is what the new year needs, an antidote to proper diet and moderation, full of self-discipline. In the Middle Ages, vanity was sinful, and those who looked into the mirror too long might see the devil peering over their shoulder. One of the most exquisite pieces in the display case is an Italian comb carved from ivory. It is hard to imagine how its gorgeous long teeth have been preserved to this day. Now it represents innocence and pride, and the simple pleasure it brings to a woman's scalp and hair is a stark contrast to the constant war that plagued women's bodies at the time.

Julian of Norwich's Revelation of the Love of God

The exhibit "Disease Woman" is a German medical illustration created around 1420, showing all the internal organs of a woman, each of which is named and labeled with the diseases associated with it. From a 21st century perspective, the strange arrangement of women's internal organs looks like a town map.

Joan du Lee's Petition to Practise Medicine, c. 1403

A historical snapshot of a midwife handing a newborn baby to its mother

Here, the story of one woman stands out. Around 1403, the widow Joan du Lee submitted a petition to King Henry IV of England, seeking permission to practice medicine throughout the country. Joan’s document provides the first evidence of women practicing medicine in the Middle Ages. The impression given by surviving manuscripts of medieval medicine is generally that it was a field occupied by men, with women unable to attend university to study medicine and therefore unable to obtain a license to practice medicine. However, despite the institutional restrictions on women, they were not completely removed from the medical profession. They took on many functions, such as being healers and caregivers in domestic and religious households, as staff in hospitals and infirmaries, and as midwives who helped women give birth and wet nurses who cared for young children.

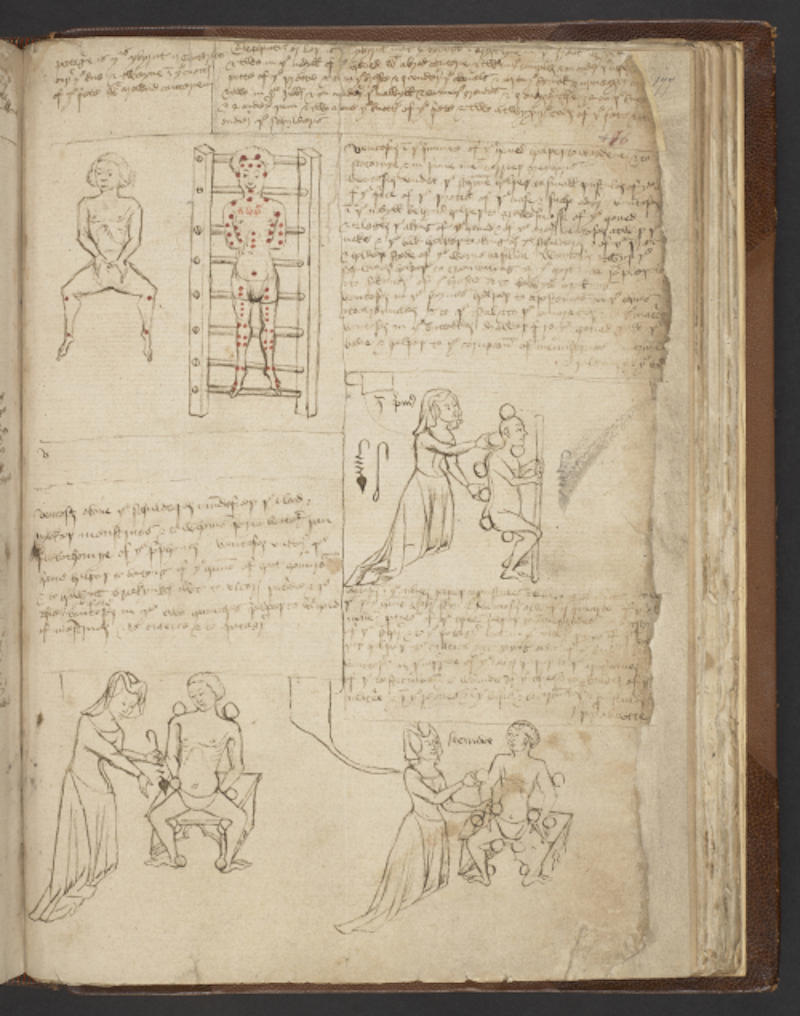

Illustrations from a medical collection showing women undergoing different medical procedures and treatments

Evidence of possible medical treatments performed by women can be found in medical treatises produced in England in the 15th century. One manuscript contains a set of drawings depicting female physicians attending to patients and performing different treatments, including a procedure called “cupping” in which heated glass cups were applied to the patient’s skin.

Illustration from a medical collection showing a female doctor cupping a patient's back

Women did take on medical roles, of course, but they also faced hostility and suspicion for doing so. Joan’s request to Henry IV hints at some of the dilemmas faced. She specifically requested a letter with the King’s seal of approval, which would effectively guarantee the legitimacy of the document to anyone who doubted her, with less obstruction or interference. Sadly, we don’t know if Henry IV granted her request. Still, her petition is a great example of a medieval woman using legal channels to continue to practice her chosen profession. Public and private, known and unknown, it’s a fascinating exhibition, but also a mysterious one.

The exhibition will run until March 2nd.

(This article is translated from The Guardian, and some content is compiled from the British Library's official website)