In human production, life and war, horses are not only useful for riding and fighting, but also beautiful for daily emotions and artistic expression. Throughout the history of human civilization development and cultural exchange, horses have traveled across the East and the West, and are "international" animals.

On January 17, the Suzhou Wu Culture Museum held a special exhibition titled "Horse - A Thousand-Year Symbol of Power from the Mediterranean to the Jiangnan Region". Through oil paintings, Chinese paintings, prints, sculptures, silk fabrics, chariots and horse equipment, pottery figurines and other types of cultural relics, it told the different relationships between humans and horses in ancient and modern times, both at home and abroad, and in different historical stages.

The relationship between humans and horses is one of the most profound, enduring and transformative in the history of human civilization. More than 5,000 years ago, humans began to raise horses for practical purposes in Eurasia, marking their first contact with horses. The subsequent domestication of horses became an important turning point that influenced warfare and promoted human mobility, trade and cultural exchange. For thousands of years, this bond has not only shaped human society, but also influenced the fate of the horse itself.

The reporter from The Paper learned that the exhibits come from collections of many Italian cultural institutions (such as the Turin Municipal Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, the Royal Museums of Turin – Museo Archeologico), as well as collections of many domestic cultural and museum institutions (the Palace Museum, Gansu Provincial Museum, etc.). With horses as the theme, the exhibition will start a dialogue between Eastern and Western cultures across time and space.

Exhibition View

Exhibition View

Chen Zenglu, director of the Wu Culture Museum, told The Paper that from being hunted to being domesticated, from playing a role in transportation and war to symbolic significance in global culture, horses have gradually become a symbol and symbol in the process of historical development, and have had a profound impact on the development of military, trade, and art. "Therefore, there are many horse-related themes in Western sculptures and oil paintings. The image of the horse itself is actually very magnificent, and its bones and muscles give us a sense of upward power. The same is true in China, and horses are also portrayed in painting and sculpture."

"This exhibition is also an extension of the 'Etruscan Exhibition' and the 'Ancient Rome Exhibition' that we held previously. Compared with the direct display of a certain civilization in the first two special exhibitions, this exhibition not only compares the image of horses in different eras in Chinese and Western culture, but also shows specific cases of how horses have played a role in the cultural exchanges between China and the West. The curation of this exhibition is more in-depth and more progressive, and we also hope to show our latest research and understanding of horses." said Chen Zenglu.

Exhibition View

Exhibition View

Horses: Everyday Life, War, and Myth

Horses are not only an indispensable helper in transportation, but also a companion for travel and hunting. The domestication of horses on the steppes of Central Asia about 5,000 years ago revolutionized how people traveled and interacted with their surroundings, and played a decisive role in the formation of Western civilization.

For example, the black lacquer high-footed plate with a horse kicking its front hooves on display dates from the 4th century BC, and the horse depicted emphasizes the ideal of balancing strength and virtue in Greek culture. The relief of a chariot in motion on display dates back to the Roman period. In ancient Greece and Rome, chariots were an important symbol of military and political power, and often appeared in monuments or reliefs commemorating military leaders and gods.

Exhibition site, relief of a chariot in motion, 1st century AD, white marble,

Exhibition site, black lacquer high-footed plate with a horse kicking its front hooves, 4th century BC

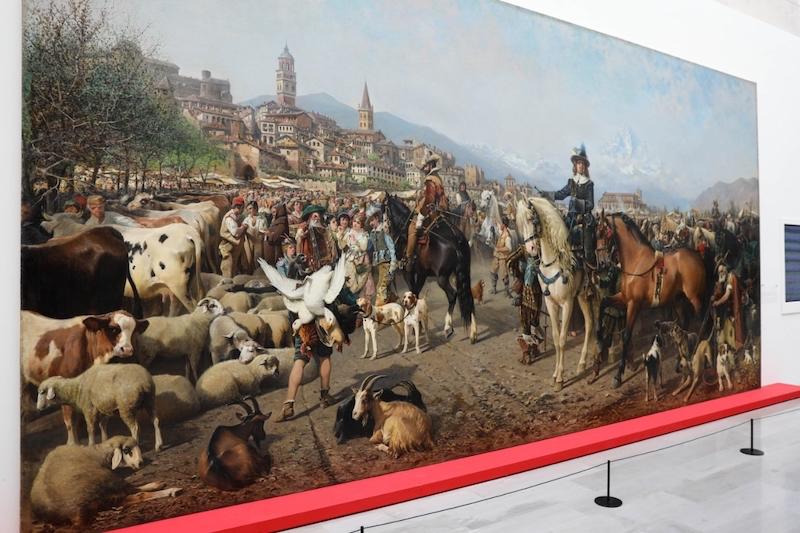

As a loyal partner of human life, horses have always been used for riding, packing and pulling carts, playing an important role in transporting goods and people, and cultivating fields. Since the 5th century, large fairs have emerged in northern France, Flanders and Germany. In the Middle Ages, these fairs held events every year, which consolidated Europe's international trade network. Horses played a vital role in this network. Ji Meijiao, the person in charge of the exhibition, told reporters that there is an oil painting on canvas "Saluzzo Fair" created by Carlo Pitara, which is one of the key exhibits. The painting is more than 8 meters long and more than 4 meters high, and delicately depicts the livestock market scene in Saluzzo.

Exhibition view, Carlo Pitara, Saluzzo Market, 1880, oil on canvas

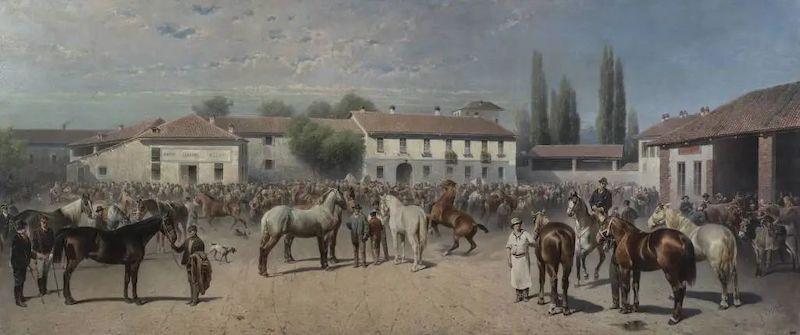

Felice Cerruti Balducci, The Moncalieri Assembly, circa 1878, oil on canvas, Museo Civico di Torino, Turin

In addition to being relevant to daily life, horses are also an important part of military life, both as mounts on the battlefield and as tools for transporting troops, weapons and supplies. Warriors who can fight on horseback are valuable resources because of their strength, speed and combat effectiveness. Knights, who are one with horses, embody Western civilization and spiritual values. Literature praises their deeds and art depicts them as models of virtue. The speed, strength and loyalty of horses have also made them the protagonists of stories and myths since ancient times.

The exhibition also features works by Giovanni Domenico Molinari, whose paintings are linked to Torquato Tasso's Jerusalem Delivered, reinterpreting the opposition between good and evil by depicting the siege of Jerusalem during the First Crusade. This story has inspired countless works of art over the centuries, all focusing on the moral themes of the epic.

Exhibition view, scene from Giovanni Domenico Molinari's Jerusalem Delivered: Horseback Combat, Armida riding between two warriors, circa 1781, oil on canvas

In the East, China had already organically combined horses and chariots in "sacrifice" and "war" as early as the Pre-Qin period. In the Western Zhou Dynasty, chariot and horse burials were inherited and developed, and the number of chariots and horses buried with the dead and the number of horses driven were directly related to the status of the tomb owner. In the Eastern Zhou Dynasty, rituals and music collapsed, princes fought for hegemony, and oversized chariot and horse burials occurred from time to time. Military operations also entered the era of large-scale chariot warfare, and the number of chariots became an absolute indicator of national strength. In the middle and late Warring States period, King Wuling of Zhao implemented the "Hu clothing and horse riding" reform. Since then, the Central Plains regime has learned the horse riding skills of nomadic peoples, and cavalry has emerged in line with the historical trend.

Bronze chariot, Eastern Han Dynasty, unearthed from Leitai Han Tomb in Wuwei City, now in the collection of Gansu Provincial Museum

After the chaos and disputes, the Qin and Han dynasties established a unified feudal empire, but they still faced the threat of the "horse-riding nation" Xiongnu. Facing this powerful opponent, the Qin and Han rulers vigorously developed cavalry, set up official horse farms in border counties, and encouraged people to raise horses by using horses instead of labor. In the Han Dynasty, Emperor Wu of Han actively introduced good horses from Wusun and Dayuan to improve horse breeds, and cultivated alfalfa to improve pastures, which greatly improved the quality and quantity of Han horses, laying the foundation for the Han government to turn its defensive position against the Xiongnu into an offensive one.

The shaping of horses by Eastern and Western cultures

Horses were important and numerous in ancient monumental sculpture. In the West, horses often appeared with gods on chariots in triumphal arches or with knights as cavalry. In Rome at the end of the empire alone, there were 22 equestrian statues, many of which were made of marble and others of gilded bronze.

In the Middle Ages, ancient images were revived in both religion and politics. Images of Jesus, the Three Magi, paladins, and archons all rode horses. The culture of the late Middle Ages in Europe was characterized by chivalry and court etiquette, and horses, as a symbol of identity, were closely related to royal power and the rule of lords. This practice has continued to the modern era, and equestrian portraits have become a privilege of the nobility, symbolizing bravery and virtue. Ji Meijiao told reporters that the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius in the exhibition hall is also one of the key exhibits. This small bronze statue is made of gilded bronze and replicates the equestrian monument of Marcus Aurelius (161-180). The prototype of this statue was first made in the Roman period and stood in the Capitoline Square in Rome. This statue is well-known, and many equestrian portraits across Europe draw inspiration from it.

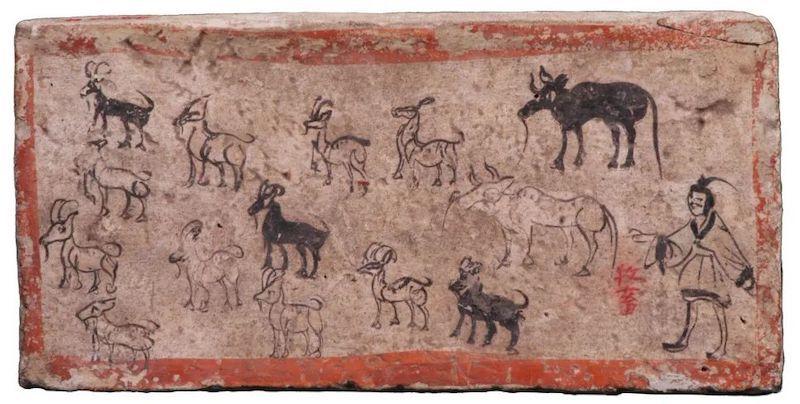

Exhibition view, Equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, 16th century, bronze, Civic Museum of Ancient Art – Palazzo Madama

In China, during the Han Dynasty, with the rising status of cavalry, horse-drawn carriages gradually turned to daily life and ceremonial purposes. For example, the Western Han Dynasty "Flying Cavalry" pottery horse-riding figurine on display shows a man riding on a horse with a majestic expression, wearing a double-layer right-fronted cross-collared uniform on the upper body, and the lower body is molded as a whole with the horse's body, wearing long boots. The pottery horse is sturdy, and the two words "Flying Cavalry" are engraved on its abdomen. Historical records record that "the Chu soldiers are light and difficult to compete with." The two words "Flying Cavalry" show the fierceness and speed of the Chu cavalry. The front of the Western Han Dynasty gold plaque on display is a bas-relief decoration, with the main body being a beast biting and fighting pattern. Two beasts have their eyes wide open, holding down a horse with their claws and biting greedily. According to research, this type of "hind hooves turned over and bitten by beasts" animal pattern originated from the Eurasian grasslands and the Great Wall area, and was popular from the late Warring States period to the middle of the Western Han Dynasty. The picture of horses and carriages traveling is a common theme in Han Dynasty portrait bricks, and it is also a common theme in Han Dynasty decorative art.

Exhibition site, gold plaques from the Western Han Dynasty

“Flying Rider” inscribed pottery horse-riding terracotta warriors and horses, Western Han Dynasty, Xuzhou Lion Mountain Terracotta Warriors and Horses Pit, Xuzhou Museum

Stone relief of a carriage and horses, Eastern Han Dynasty, Xuzhou Han Stone Relief Art Museum

The spring breeze is full of vigor and the horse's hooves are galloping

During the Wei, Jin, Southern and Northern Dynasties, China once again fell into division and chaos. Frequent wars led to a surge in demand for horses. The large-scale migration of various ethnic groups objectively promoted the first ethnic integration in Chinese history. In particular, the Xianbei and other northern grassland ethnic groups moved to the south of the Great Wall, making farmland increasingly pasture-based. The rise of the horse industry in the Northern Dynasties was second to none before the Tang Dynasty.

The Tang Dynasty was the most prosperous period in Chinese history, and horse breeding was the foundation of its prosperity. Tang horses were strong and plump, with extraordinary spirit, reflecting the atmosphere of the prosperous Tang Dynasty. In terms of military, thanks to exchanges and actual combat with grassland peoples such as the Turks and Tubo, the Central Plains cavalry in the Tang Dynasty changed from "armored cavalry" to light cavalry.

"Pastoral Painting" brick, Wei and Jin Dynasties, unearthed from Tomb No. 1 in Xincheng, Jiayuguan, now in the collection of Gansu Provincial Museum

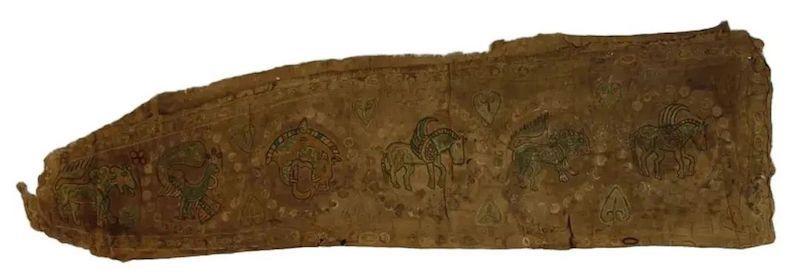

Sword arm with embroidered animal patterns, Northern and Southern Dynasties, collected, Gansu Provincial Museum

A terracotta warrior on horseback, Northern Qi, unearthed in Baigui Town, Qi County, now in the collection of Shanxi Museum

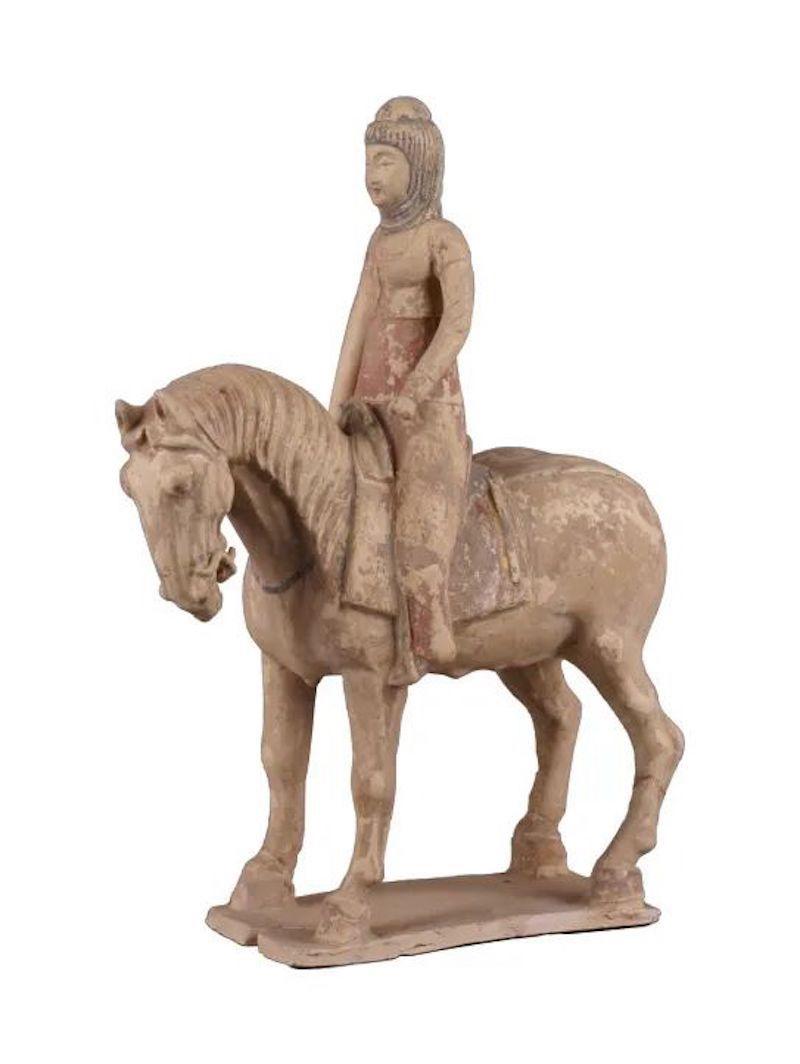

In the Tang Dynasty, riding horses was not only a military necessity, but also a social trend. Horse riding was popular in the Tang Dynasty, and women could also go out on horseback. In the exhibition, many Tang Dynasty painted figurines show the riding appearance of the time. For example, the painted male horse-riding figurines and the painted glazed pottery female horse-riding figurines on loan from the Zhaoling Museum. The former focuses on the strong body of the horse ridden by the man, which is round but not bloated, and agile but elegant. The latter depicts a woman wearing a short jacket and a long skirt, riding on a horse with her feet in the stirrup, with a leisurely look, reflecting the openness and tolerance of the early Tang Dynasty, cultural diversity, and the trend of women pursuing openness and freedom.

Painted glazed pottery figurine of a female horse rider, Tang Dynasty, unearthed from Zhang Shigui’s tomb, now in the collection of Zhaoling Museum

As a link for cultural exchange

After the Tang Dynasty, the northern nomadic peoples such as the Khitan, Jurchen, and Mongolians who lived on horseback, kept horses as their companions, loved horses and were good at riding, admired martial arts, and relied on their powerful military strength to move south to compete for the Central Plains and even roamed across the Eurasian continent.

During the Yuan Dynasty, Italian Marco Polo arrived in Shangdu and wrote The Travels of Marco Polo, which was the most detailed record of European travel in Asia at that time and an important document for the study of ancient geography and Asian history. Marco Polo's travel notes confirmed the importance of horses in medieval Eurasian society. From battlefields to markets, from grasslands to palaces, horses, as silent protagonists, run through his narrative and become a common bond that connects the different cultures that changed during the journey.

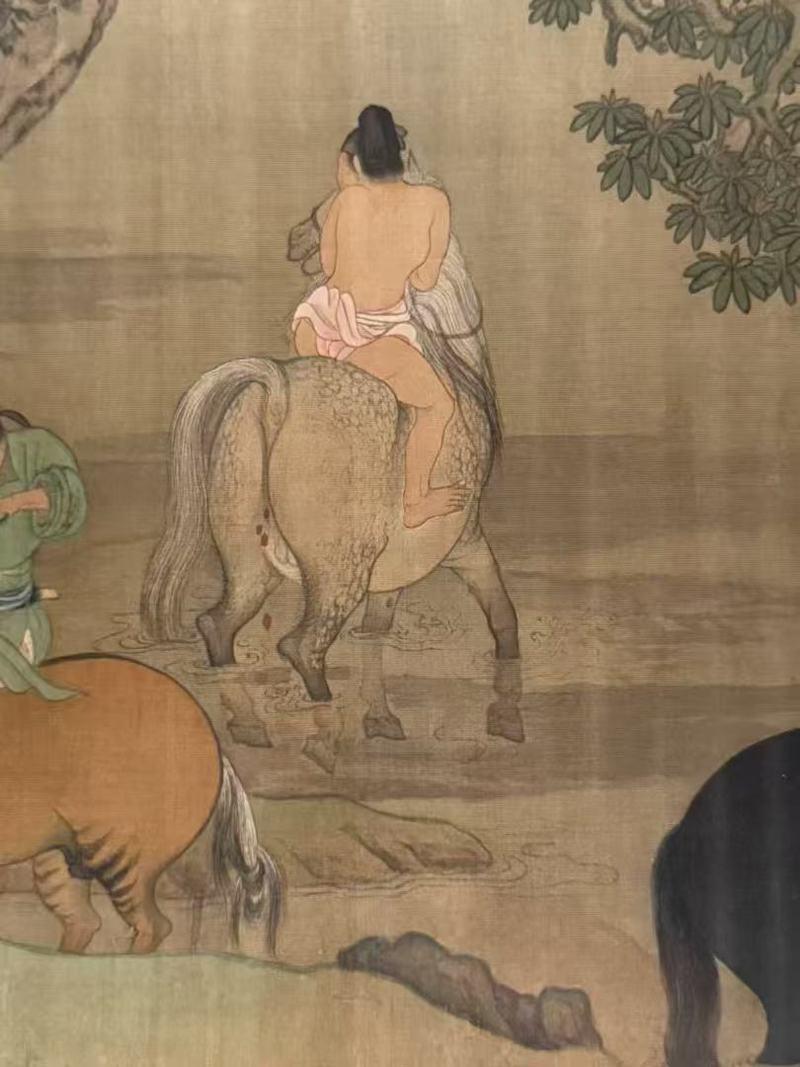

The exhibition also features Yuan Dynasty horse artifacts. The highlight is the "Horse Bathing Scroll" by Zhao Mengfu, a master of the Yuan Dynasty. This scroll depicts a scene in the summer woods where the Xiguan, who is in charge of raising horses, is bathing the horses to cool off. In the painting, you can see a stream of clear and bright water, and there are sycamores and weeping willows beside the stream. The horses are also in different and vivid postures, some drinking from the stream and chewing grass, some unsaddled and leaning against a tree, some sitting on the ground with their heads held high, and some lying or looking around, all with vivid charm.

Exhibition site, Zhao Mengfu's "Horse Bathing Scroll"

As the curator and one of the planners of the exhibition, Chen Zenglu told reporters that his favorite exhibits are Carlo Pitara's huge oil painting and Zhao Mengfu's "Horse Bathing Scroll", both of which are classic depictions of horses in Eastern and Western art. "The depiction of horses in Western art is based on realism. From early sculptures to later oil paintings, we can see the strength and majestic beauty of the horse's bones and muscles. China, representing the East, has both realistic aspects, such as works after the Tang Dynasty, including those by Zhao Mengfu of the Yuan Dynasty, which are mainly realistic, and early works also have exaggerated, abstract and symbolic expressions. In this process, there has always been a lot of communication and reference between Eastern and Western art."

Bathing Horses (partial)

Bathing Horses (partial)

Note: The exhibition is jointly organized by Wu Culture Museum, Turin Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Turin Royal Museums – Archaeological Museum, Savoy Gallery, Turin Museum of Ancient Art – Palazzo Madama, Florence Alinari Photography Foundation (Alinari Archives), Palace Museum, Gansu Provincial Museum, Shanxi Museum, Inner Mongolia Museum, Xuzhou Museum (Xuzhou Han Dynasty Stone Carving Art Museum), Zhaoling Museum and other domestic and foreign cultural and museum institutions. The exhibition has received strong support from the Italian Consulate General in Shanghai, the Cultural Office of the Italian Consulate General in Shanghai, the Turin Museum Foundation and the Department of Veterinary Medicine of the University of Turin.

The exhibition will run until May 18th.