Born in the Daoguang period, Shen Zengzhi (April 11, 1850 - November 21, 1922) witnessed the great changes in modern China. During the transition from the old to the new, he made great contributions to the study of classics, history, poetry, phonology, and the history of Northwest and Southeast Asia. He was proficient in geography, Buddhism, Taoism, medicine, ancient criminal law, version catalogue, calligraphy and painting, music, etc., and was known as a "universal man".

"What is a Genius: Shen Zengzhi in the Perspective of Statecraft", compiled by Zhejiang Provincial Museum (chief editor: Lu Yi), was recently published by Xiling Seal Society Press. This book presents Shen Zengzhi's academic life from multiple perspectives in the context of worldly affairs, exploring his "comprehensiveness". This article focuses on his knowledge of epigraphy.

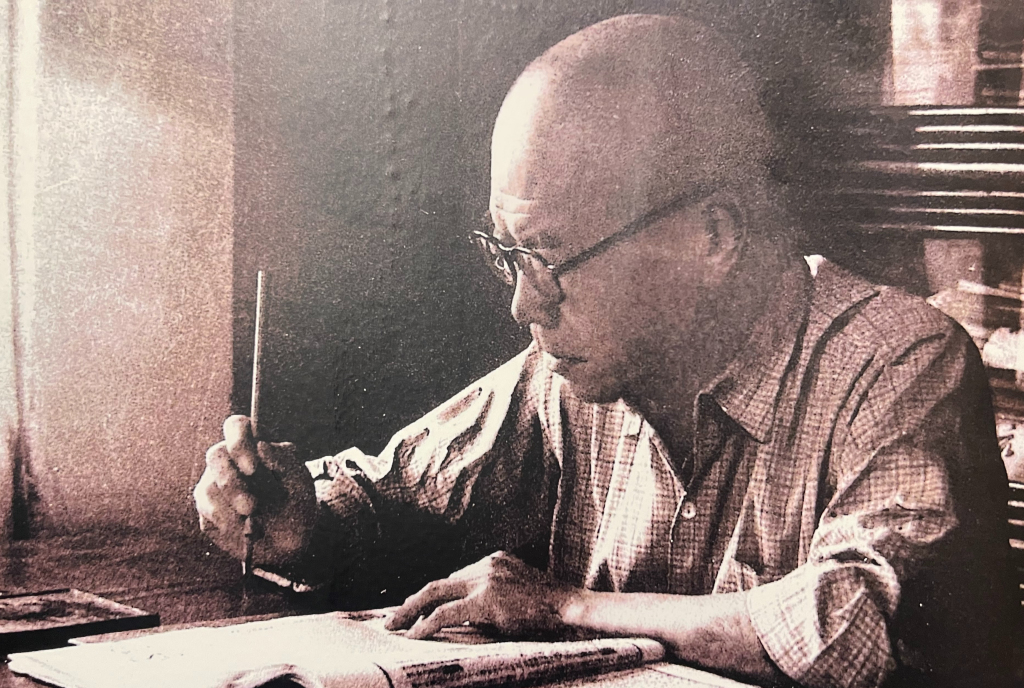

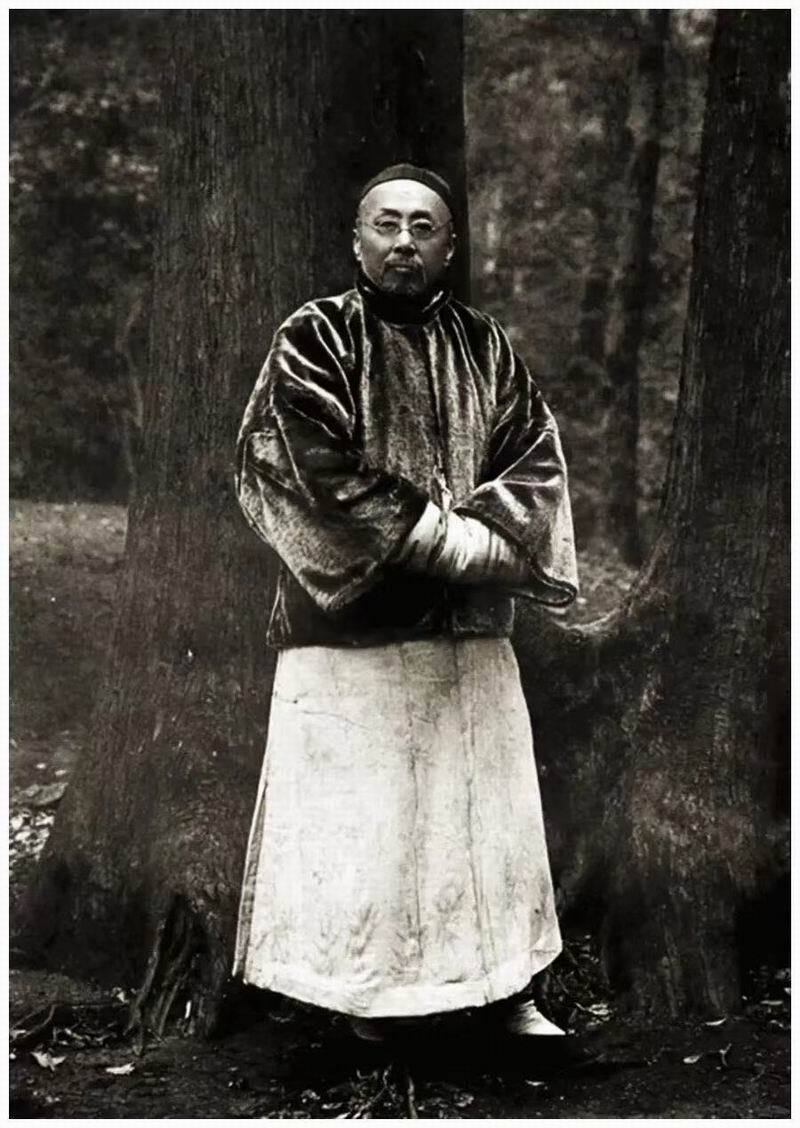

Shen Zengzhi

Shen Zengzhi claimed that "calligraphy is better than calligraphy talent" and only regarded calligraphy as a minor skill. However, as the most representative first-class calligrapher in the late Qing Dynasty and early Republic of China, calligraphy is always a topic that cannot be avoided when discussing Shen Zengzhi.

His fellow Jiaxing native Jin Rongjing once commented on Shen's lifelong learning: " Mr. Shen was good at calligraphy at an early age, and learned from Bao An and Wu. When he was young, he liked Zhang Lianqing. He wanted to write an article to explain the source and change of his calligraphy and the reason for his success. Later, he moved from calligraphy to stele, integrating the northern and southern styles of calligraphy into one, creating intricate changes to express the wonders in his heart, almost forgetting about paper and pen, and only thinking about what he was doing. Although he was classified as a stele calligrapher, Shen Zengzhi did not reject traditional calligraphy. When it comes to the calligraphy of predecessors, his attitude is to collect widely, extract the essence and make extensive use of it, and he is good at absorbing nutrition from all sides for his own use. Throughout his life, Shen continued to practice calligraphy, leaving behind a considerable number of imitation works, which can verify the direction of his calligraphy.

Shen Zengzhi's imitation of Wang Xizhi's "Zhanqi Hutao Tie" in cursive script, Zhejiang Provincial Museum

In the era when the stele school was popular, Shen Zengzhi attached great importance to learning from Han and Wei steles such as the Zhang Qian Stele, the Zheng Wengong Stele, the Cuan Baozi Stele, and the Cuan Longyan Stele. He also devoted equal energy to carefully copying and studying the typical masterpieces of "Two Wangs" calligraphy, such as "Seventeen Posts", "Book of Calligraphy" and "Chunhua Ge Tie". In addition, Shen was also the first calligrapher at that time to include the Dunhuang manuscripts and Northwest Han bamboo slips unearthed by archaeological excavations as models for calligraphy learning for reference and study. From his works, we can see that when copying the stele, he does not lose the fluency of the calligraphy, and adds the solemnity of the stele to the copying. The brush-writing technique of spreading the brush and turning the finger brings a raw and ancient interest. It can be seen that Shen's calligraphy copying It is not a blind adherence to the past, but the result of careful consideration.

Shen Zengzhi's regular script copy of "Zheng Wengong Stele" and his own poem in official script, collected by Zhejiang Provincial Museum

Shen Zengzhi, Four-panel Painting of Calligraphy and Inscriptions, Collection of Zhejiang Provincial Museum

In terms of calligraphy, Shen Zengzhi also inherited the ideas of his predecessors Ruan Yuan and Bao Shichen in advocating Northern stele, but he did not unilaterally promote stele and suppress calligraphy like Kang Youwei did. The important difference is that Shen believed that stele and calligraphy were not clearly divided. Deviate from and try to trace the calligraphy style of Zhong and Wang through Northern inscriptions. When he wrote a postscript on the famous Northern stele "Zhang Menglong Stele", he compared it one by one with the "Longzang Temple Stele" of the Sui Dynasty and the famous small-character calligraphy works of Wang Xizhi and Wang Xianzhi, pointing out the stylistic comparability between the steles and the calligraphy works.

Shen Zengzhi's cursive script excerpt from Bao Shichen's "Yizhou Shuangji·On Calligraphy" screen Zhejiang Provincial Museum

Explanation: When ancient people discussed regular and running scripts, they generally considered it best to not lose the meaning of seal and running scripts. Later generations tried to find an explanation for it but failed, so they ended up using straight dots and slanted strokes to represent it. The ancients had a fixed method for writing, and the size of the characters depended on their shape. The characters on the "Wuding Jade Buddha Record" are half an inch square, the characters on the "Diao Huigong" and "Zhu Junshan" are half an inch square, the characters on the "Zhang Menglong" and other stele characters are an inch square, the characters on the "Zheng Wengong" and "Zhongmingtan" characters are two inches square, and the characters on the plaques of each stele are four or five inches square. inch. If cursive writing is not combined with regular writing, it will be too meticulous; if regular writing is not combined with cursive writing, it will not be a calligraphy. The true style uses dots and strokes as the form and turns them into temperament; the cursive style uses dots and strokes as the temperament and turns them into form. Although the interactions are different, they are generally related. The brushwork of "Zhu Junshan Stele" is particularly unrestrained, and the characters are square and neat yet somewhat unusual. His running script is often crooked, with majestic and elegant structure. The fourth brother Zheng Lu is from the family of the old man Mei.

Like many literati and scholars since the Qianlong and Jiaqing periods, in addition to collecting ancient books, Shen Zengzhi also had a hobby of collecting rubbings of inscriptions and calligraphy. During his official travels, he often lingered in factories and shops. After he was 60 years old, he lived in seclusion in Shanghai. Shen Zengzhi continued to purchase a large number of rubbings of stone inscriptions. The Zhejiang Museum currently houses more than 70 inscriptions and calligraphy works donated by the descendants of the Shen family, excluding photocopies, which account for a large proportion of the collections in various public and private institutions.

Judging from the types of Hairilou inscriptions and calligraphy in the museum's collection, there are 6 types of Han and Wei inscriptions, 9 types of Sui and Tang inscriptions, and the rest are calligraphy works from past dynasties. From this, we can see Shen's criteria for selecting inscriptions and calligraphy. First, he did not pursue precious inscriptions and calligraphy. There were almost no rare copies of famous inscriptions and calligraphy from the Song Dynasty that were collected by famous artists and inscribed with many inscriptions. His inscriptions were basically rubbings from the Qing Dynasty, and his calligraphy was also based on rubbings from the Ming and Qing Dynasties. The pioneers are the main ones. Secondly, Shen attached great importance to engraved calligraphy, especially the calligraphy of Zhong and Wang. Even incomplete copies were treasured. He would often collect different versions of the same calligraphy, such as the original and reprinted ones, and compare and evaluate them through inscriptions, postscripts and comments. .

Shen Zengzhi's postscript to Lanting Preface, Liu's copy of Yingjing edition, Zhejiang Provincial Museum

Note: This work is selected from the rubbings of the Huangting Sutra inscribed by Chen Xijun in Siguzhai, and Chen’s own inscription reads “Shaoxing Imperial Household Edition, Copy by Zhu, Lanting, Liu, and Yingjing Edition”. He wrote many paragraphs in small characters in red and black ink, and later copied the "Lanting Preface" by Gan Wenchuan of the Yuan Dynasty.

The Yingshang version of the Lanting and Huangting stone inscriptions, also known as the Siguzhai version, was unearthed in the eighth year of the Jiajing reign of the Ming Dynasty (1529) or the end of the Wanli reign of the Ming Dynasty, from an ancient well in Yingzhou (now Fuyang City, Anhui Province). Therefore, it is also called Yingjing version. The stone tablet is engraved with "Lanting Preface" on one side and "Huangting Sutra" on the other. There is a seal script "Siguzhai Stone Carving" in front of "Huangting" and two seals "Yongzhong" and "Mo Miao Bi Jing" behind "Lanting". The inscription "Tang Lin Silk Edition" is in regular script in small characters, and is twenty-one characters short of the general version. Early rubbings can be seen with inscriptions carved by Ming people. The original stone was destroyed after the magistrate Zhang Junying copied the stele in the late Ming Dynasty. When it was rediscovered in the Qing Dynasty, only fragments remained, and the remaining stone is now in the Anhui Museum.

The Yingshang version was classified as part of the Zhu Lin version system and was highly valued after it was unearthed. Shen Zengzhi, based on Sang's Lanting Research, believed that it was the Southern Song imperial collection with 21 missing characters. According to this, it was originally acquired by Jiang Changyuan as recorded in the History of Calligraphy. The yellow silk copy of the Su family; Wang Lianqi believed that it was a re-copy of the Imperial Palace copy. Siguzhai was the studio name of a Yuan Dynasty person, so it should be a Yuan edition.

It is rare to find an authentic Yingshang version that is intact, and there are many reprints. The most common and most finely engraved version is almost indistinguishable from the original. The red rubbings collected by Shen Zengzhi are the reprinted copies. Shen pointed out that the difference between the original and the original is that the word "miao" is printed in "miao ji jing". The reprinted copy is wrong, and he believes that this reprinted copy is the same as Yang Bin's Tie Han Zhai. The reprinted edition by Liu Gongyong mentioned in the "Book Postscript". In addition, Shen Zengzhi used the dimensions recorded in the Shaoxing Imperial Household Calligraphy and Painting Style to compare the relationship between the Shaoxing Imperial Household Lanting and Yingshang versions, which shows his understanding of the dimensions, the errors in the copies, the differences in the ink writing and the engraving. There is a keen focus on the issue. There are four such reprints of "Yingshang Lanting" in hiding, two in red and two in black.

This collection orientation was different from other officials in the late Qing Dynasty, such as He Shaoji, Weng Tonghe, Fei Nianci, Pan Zuyin, Bao Xi, and Luo Zhenyu, who were famous for their collection of inscriptions and calligraphy. It may have been due to objective factors such as financial constraints. , but it fits Shen Zengzhi's identity as a scholar.

Because there are no special articles such as Ruan Yuan's "On the Northern and Southern Calligraphy Schools" and "On the Northern Stele and Southern Calligraphy", Bao Shichen's "Yizhou Shuangji" or Kang Youwei's "Guang Yizhou Shuangji", Shen Zengzhi's calligraphy theory has not been able to be widely used. It has reached the status it deserves, but Shen's profound learning and broad knowledge give his calligraphy theory considerable depth and breadth, and his discussions that are inspired by his feelings often contain inspiring insights. His views on calligraphy are mainly preserved in the form of inscriptions and postscripts, scattered on the stone tablets and calligraphy he saw or collected, and some are notes and letters. Shen's inscriptions and postscripts on stone tablets and calligraphy and his calligraphy practice can often refer to each other and complement each other, which is " It is a concentrated embodiment of "using learning to support books". Among Shen's inscriptions and postscripts compiled by later generations, inscriptions and postscripts on steles and calligraphy account for a very large proportion, becoming an important component that cannot be ignored when evaluating Shen's academic achievements.

Contemporary scholar Wang Qian pointed out that the most prominent feature of Shen Zengzhi's inscriptions is the high density of ideas, which also makes it difficult for later generations to interpret them. Shen's inscriptions often contain a lot of information. Not only do they quote from classics, but they also often have their own unique insights. This is first of all due to his broad and comprehensive knowledge structure. As a representative scholar in the late Qing Dynasty, Shen Zengzhi was well versed in classics, history, phonology, geography, Buddhism, Taoism, medicine, criminal law, version catalogs, inscriptions, calligraphy and painting, etc. , he was proficient in all of them; in addition, Shen had meticulous and sharp insight and comprehensive thinking ability, so when writing inscriptions on stone tablets and calligraphy, he could not only cite extensive references for textual research, but also make concise and appropriate comments. Just as Kang Youwei praised Shen: " My son's learning is broad and comprehensive, and his arguments are profound and detailed. He often makes judgments in one or two words and hits the nail on the head. This is impossible without extraordinary knowledge, love of learning and deep thinking." (Letter to Zipei, the Minister of Punishment)

Shen Zengzhi's postscript to Lanting Preface, Liu's copy of Yingjing edition, Zhejiang Provincial Museum

The "Hai Ri Lou Inscriptions and Postscripts" section of "Five Types of Hai Ri Lou Bibliography and Postscripts" compiled by Xu Quansheng and Liu Yuemei is divided into two volumes: "Inscriptions and Postscripts" and "Postscripts". The Postscripts section is further divided into single posts and collections. If we count the number of posts alone, the number of postscripts exceeds that of stele postscripts, which corresponds to the number in the Zhejiang Museum's collection. Nearly two-thirds of the stone tablets and calligraphy in the Zhejiang Museum's collection have inscriptions by Shen Zengzhi himself, many of which were not included in the "Meisou Inscriptions" published in the Republic of China. Taking the inscriptions on rubbings of engraved works, which account for a larger proportion, as an example, they can well reflect the characteristics of Shen Zengzhi's calligraphy. First, Shen Zengzhi's familiarity with the previous discussions on traditional calligraphy can be seen everywhere. Second, Shen Zengzhi was diligent in comparing the similarities and differences between versions and published new theories on this basis.

For example, as the ancestor of the collection of calligraphy, Chen successively purchased many copies of Chunhua Ge Tie, including fragments and volumes. He not only copied and supplemented them himself, but also proofread and wrote inscriptions one by one with reference to the previous documents. The source is very familiar. When studying the so-called Jia Sidao version (i.e. the Southern Song Shaoxing Imperial College version), Shen first proposed in his postscript that in addition to the two Ming versions, the Shanghai Pan version and the Gu version, there is another version, the Wu version, which has not been mentioned by previous scholars. This theory was engraved by Yuan Shi of the Men School (Yuan Ruo). It had an influence on another great calligrapher, Zhang Boying, and later researchers, and its influence continues to this day.

In addition, regarding the origin of the Southern Song Quanzhou version, he proposed two hypotheses: one was engraved by the Shibosi, and the other was transmitted to Quanzhou by the Nanwai Zongzhengsi via sea. A very significant innovation in the field. As for single posts, Chen is deeply interested in a series of representative works of the "Two Wangs", and is particularly interested in "Lanting Preface". Of course, as the first running script under the name of Wang Xizhi, "Lanting Preface" has been obsessed with many people since ancient times. Shen Zengzhi's "Lanting Preface" inscriptions involve versions, textual research, brushwork and other aspects. The richness of the content can be compared with the appreciation of Weng Fanggang, Wu Yun and other The research of famous scholars is on par with that of other scholars.

For example, the original copy of the Lanting Preface in the Bohai Collection in the Ming Dynasty in the Zhejiang Museum is the one with the most inscriptions and comments. The original copy was printed by Chen from Haining in the late Ming Dynasty using the half-printed Lanting Preface in his collection. It occupies a large position in the handed-down imitation system. Special status. There are seven sections of inscriptions by Shen before and after the post, as well as red-pen annotations in the post, which can serve as a typical epitome of his inscriptions on steles and calligraphy.

The original copy of Lanting Preface from Bohai is in the collection of Zhejiang Provincial Museum

Note: Sha Menghai signed the outer cover, Shen Zengzhi signed the inner cover "Bohai Zangzhen engraved Lanting, the leading characters are from Shanben", and inscribed in small characters "Song Shaoxing Imperial Household Edition, Ming Chen Jixi Edition, Yugang Edition, Zhizhi Pavilion Edition This edition, the edition printed by You Tianxi, and the edition printed by Zihuitang. There are seven sections of Shen's inscriptions and red and black ink proofreading notes.

This is a rubbing from the middle and late Qing Dynasty, from the second volume of "Bohai Zangzhen Tie" collected and engraved by Chen Fushen of Haining in the Ming Dynasty. Because the 28-line version of "Lanting" is cut into half a line per line, it is also called the half-line version. According to its characteristics, it belongs to the "Ling Zi Cong Shan" system and previous generations believed that it was a copy by Chu Suiliang. However, "Lanting" is followed by inscriptions by five Northern Song calligraphers, as well as a long inscription by Mi Fu and an authentication inscription by Mi Youren, which are consistent with the characteristics of the Su Shunyuan version recorded in "History of Calligraphy". This original work was very famous in the late Ming Dynasty. In addition to the authentic version kept in Bohai, there are also engraved versions by the Wu family in Shanzuo and the Cha family in Haining (namely the version engraved by You Tianxi). The Bohai Zangzheng version was originally missing the seventh, eighth and ninth lines.

The two versions of the Lanting by Zhu mentioned in Shen's postscript are originally kept in the Shanghai Library. One is the "Ling Zi Cong Shan Ben" engraved by Zhang Cheng of the Southern Song Dynasty, which was reprinted in the Ming Dynasty's "Yugangzhai Calligraphy Collection" and the other is the "Zihui" in the Qing Dynasty. "Tang Fa Shu" was reprinted. One is the Ming Dynasty Chen Jian engraved version, the original copy is kept in the Palace Museum, it is one of the copies made by Lu Jishan in the Yuan Dynasty, and does not belong to the "Ling Zi Cong Shan" system. The Shaoxing Imperial Household Edition mentioned in Shen's postscript can be found in "Sang's Lanting Examination". There is also a Southern Song Dynasty Imperial Household Edition. The rubbings handed down include the Song Dynasty rubbing "You Xiang Lanting Jia No. 2" in the collection of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. In the early Qing Dynasty, Sun Chengze copied it and engraved it in "Zhizhige Tie".

Book cover of "What is a Wise Man: Shen Zengzhi in the Perspective of Economics"

Note: This article is excerpted from What is a Wise Man: Shen Zengzhi in the Perspective of Economics, which is divided into five parts: Criminal Law, Geography, Buddhism, Poetry, and Calligraphy, and is accompanied by the latest research papers 6 It contains more than 300,000 words and 500 pictures, and was co-authored by 15 scholars from various fields.