Under the brush of Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840), the charm of nature is not limited to direct description, but also the habitat of emotions and souls. The concept of romanticism is not only reflected in the interweaving of light, shadow and color on the canvas, but also in the secret resonance between landscape and heart.

On the occasion of the 250th anniversary of Friedrich's birth, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York opened its "Caspar David Friedrich: Soul of Nature" on February 8. As the artist himself said, "The mission of a work of art is to perceive the spirit of nature, immerse and absorb it with all your body and mind, and then present it in the form of a painting." Through the works, the exhibition invites the audience to appreciate the poetry of nature and the soul.

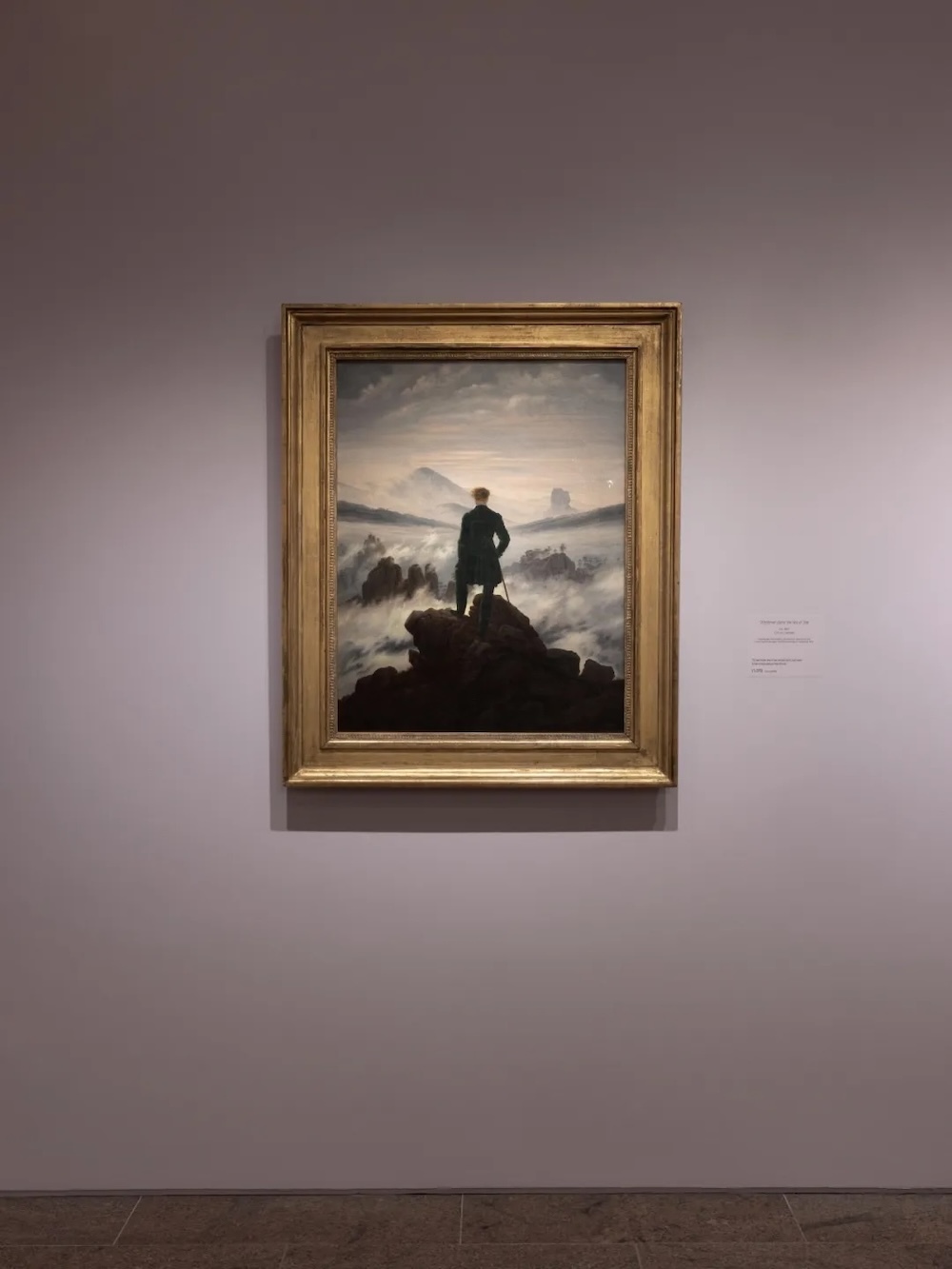

Friedrich, Wanderer on the Sea of Fog, circa 1817. This work has never been exhibited in the United States. This time, it is on loan from the Hamburger Kunsthalle in northern Germany, an exception.

After a long climb, the weather finally cleared up and we looked into the distance, gazing at the fog that had gathered beneath the rugged rocks. Only sparse grass peeped out from between the exposed rocks.

Yet, as we peered out through the thin mountain air, it was not ecstasy that overwhelmed us, but a touch of melancholy. The famous painting, Wanderer on the Sea of Fog, seemed to lack some detail, as if washed away of its uniqueness. Between us and eternity, between human understanding and the nature of the universe, lay a stubborn, vague white cloud.

The lonely wanderer in emerald green velvet has become a metaphor for Germany itself, and has been copied and parodied countless times. Now on the facade of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, this lonely hero turns his back on Fifth Avenue and looks into the distance.

Yet “Nature’s Soul” is more than a celebration of this iconic Romantic figure; it offers an unexpected surprise for viewers who are used to associating Friedrich and early 19th-century art with tranquility. Curated by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in collaboration with three German museums, the exhibition features more than 80 paintings and drawings, including images of rocks gleaming in the moonlight, a solitary cross in an evergreen forest, and a lonely German standing on a shore gazing into the distance.

Exhibition site

Compared to the related exhibition held in Germany last year to commemorate the 250th anniversary of Friedrich's birth, this exhibition is only about half the size. At the exhibition in Hamburg, Germany, Friedrich's sensitivity and delicacy in his sketches are amazing. He paid great attention to the shadows of stones and the texture of leaves, turning a lifeless rock into a reflection of the soul.

At the Met, this uncanny connection between the part and the whole may be less apparent, but the core achievement of Friedrich’s art remains clear: his spontaneous, sometimes mysterious gaze at the natural world, and his unparalleled ability to give a landscape a whole worldview. Curators Alison Hokanson and Joanna Sheers Seidenstein make a strong case for the value of landscape painting—an art form that declined in the 20th century but is now being recognized again as global temperatures continue to rise.

Most importantly, the exhibition shows the turmoil in Friedrich’s woodlands and meadows—war, nationalism, religion, industrialization, the external world is changing, and the internal world is also changing: anxiety and nostalgia. It is this dual instability—this psychological and real “climate change”—that makes Friedrich and the Romantics a kind of spiritual guide.

Friedrich, Landscape with Shepherds on the East Coast of Rügen, 1805-1806, brown ink and pastels and opaque white lacquer on pencil on rag paper, partial outlines in black and brown ink

Friedrich was born in 1774 in the Baltic port city of Greifswald, which is now part of Germany but was then a Swedish royal dependency. At the age of 20, he went to Denmark to study art. The Copenhagen Academy of Fine Arts taught students how to depict the human body, first by copying plaster casts of classical sculptures and then by sketching nude models. In the exhibition, a self-portrait of his youth - with his gaze, searching eyes, and pursed lips - proves that these lessons had a profound impact.

Friedrich, Self-Portrait, 1800, black chalk on linocut paper

But Friedrich did not like his Danish education, so he abandoned it and moved to Dresden, a city that had two attractions for him: Saxony’s art collection, then as now, was one of the richest in the world; more importantly, this German land had become a burgeoning center for poets, philosophers, and artists.

His career started slowly, and it wasn’t until he was 30 that he really found how to express emotion through landscape painting - he painted a series of vast and lonely pictures in the emerging sepia pastel technique. The passionate yet simple sepia pastels in the second room of the exhibition are stunning. The sun sets over the Baltic Sea, illuminating the rocks of a desolate coast. A shepherd walks along the coastline under an empty sky that takes up more than three-quarters of the picture.

Friedrich, View of Alcona at Moonrise, 1805-1806, brown ink and pastel on pencil on rag paper, partial outlines in black and brown ink

Friedrich, Moonrise over the Sea, 1835-1837, brown ink and pastel on a pencil on rag paper, partial outlines in black and brown ink

No one before Friedrich had distilled landscapes into such a mood and desolation. His work is meticulously observed and impeccably executed – in fact, there are almost no brushstrokes in Friedrich’s paintings, in stark contrast to the dynamic compositions of his English contemporaries Turner and Constable. However, his perspective is highly unusual, and his paintings never depict an Arcadian pastoral landscape. The few figures in the painting seem small and forgotten in the face of the rocks and the sea.

Friedrich, The Evening Star, circa 1830

With these sepia-toned landscapes, and later works of forests, boulders, and glaciers, Friedrich rejected the scientific and rational tendencies of academic art, instead prioritizing individual emotion. This break may be imperceptible to modern viewers, who are so used to seeing art as a vehicle for personal expression. But in the history of Western culture, this personalization of expression was a sea change—one that the German sociologist Georg Simmel saw as a hallmark of the Romantic era. In 18th-century France, he noted, especially after the Enlightenment, “the individual completely freed himself from the bonds of guild, blood, and church.” By the time of Friedrich’s Germany, “individuals began to wish to be distinguished from one another.”

In other words, for these Romantics, the image of citizenship shaped by the Enlightenment and the French Revolution seemed too abstract and mechanical. The self-identity that Friedrich and his friends sought must be more spiritual, more ethical, and closer to nature. This kind of freedom is not innate, but must be shaped through moral and aesthetic cultivation.

Friedrich, Two Men Gazing at the Moon, 1825-1830, oil on canvas. The painting depicts two men standing in front of a half-fallen oak tree, looking at the crescent moon in the night sky.

This sense of freedom permeates Friedrich’s art and is the most exciting part of the exhibition – the constant search for true emotions in nature, even though he knew he could never reach the absolute truth of the world.

This can be felt in many of Friedrich's works: in the figure of the two friends leaning on each other, gazing at the crescent moon above the half-withered oak tree; in the woman with outstretched arms, facing the hillside at sunrise or sunset; in the Wanderer on the Sea of Fog, standing high above, immersed in the mist. These Germans not only longed for freedom, but also for uniqueness.

Exhibition site

Enlightenment thinkers viewed literature as a tool for exploring an ideal world, while Romantic writer Heinrich von Kleist created novels and plays in which passion prevailed over reason. Enlightenment philosophers believed that reason led to truth, while Romantics such as Friedrich Schlegel emphasized the limitations of reason and put personal experience first. For those Enlightenment thinkers who believed that religion was superstition, Friedrich used the figure of the monk in "The Monk on the Seashore" to symbolize the eternal unknown.

Friedrich, Monk by the Sea, 1808-1810, oil on canvas. Depicts a small figure standing in front of a vast, dark, empty seashore, with a sky full of dark clouds.

The true sublime in Friedrich’s work is not the mountains or the trees, but the subjective impact of nature on the painter and the viewer—how the landscape shapes an observer in history and time. The Romantics called this “Erlebniskunst,” the art of feeling over seeing. For Friedrich, landscape is always a journey into the unknown—both geographically and internally.

“Strangers come, strangers go,” goes Schubert’s Winterreise. Towards the end of the exhibition, we see Friedrich’s sepia-toned paintings of his later years—cave, cemetery, forgotten years after he gave up painting, when this most German of artists depicted the German landscape as an almost foreign land. And what makes this exhibition so relevant is the strangeness that Friedrich always maintained in the landscape—and the deep longing he placed among the rocks and pines—a longing for God, a longing for the distance.

Friedrich, Moonrise over the Sea, 1822, oil on canvas

Note: This article is translated from Jason Farago’s exhibition review. The original title is “Friedrich: A Lone Wanderer Finding Direction in the Mist”. The exhibition will last until May 11