Wang Shimin (1592-1680) is an important figure in the history of painting in the late Ming and early Qing dynasties. He studied under Dong Qichang and had a rich collection of paintings. He copied famous works from the Song and Yuan dynasties. What kind of person was Wang Shimin besides being a painter? Recently, the book "Beyond Painting: An Interpretation of Wang Shimin's Lost Letters" written by scholar Wan Xinhua was published by Liaoning Fine Arts Publishing House. The book compiles nearly ninety lost letters of Wang Shimin for interpretation. As rare textual relics, these letters contain a variety of rich information, which are meaningful for people to understand Wang Shimin, his art, and even the career of literati in the late Ming and early Qing dynasties and the way of artistic and cultural exchanges.

Book cover of "Beyond the Painting: An Interpretation of Wang Shimin's Lost Letters"

Wang Shimin, also known as Xunzhi and Yanke, was a native of Taicang, Jiangsu. In his early years, he was appointed Shangbao Cheng by virtue of his ancestor's influence, and later promoted to Shaoqing of Taichang Temple. He was known as "Wang Fengchang". In the 13th year of Chongzhen (1640), he resigned from office and lived in seclusion in Xitian Villa, also known as Xilu Old Man.

As an important figure in the history of painting in the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, Wang Shimin learned painting from Dong Qichang (1555-1636). He was personally acquainted with him when he was young. He started with the Southern School and had a deep understanding of Huang Gongwang's ink method. In his old age, he became more divine, and his brushwork was smooth and elegant, becoming a leader in the painting world. He paid great attention to the composition of brush and ink and its abstract expression. He recreated the nature in his mind through the brush and ink paradigms and experiences of the ancients in summarizing natural scenery. He not only refined the procedures of trees, rocks, mountains, water, and houses, but also refined the laws of the unity of opposites such as virtuality and reality, lightness and heaviness, opening and closing, and ups and downs in the combination of brush and ink. He "participated in the creation of nature and connected the chaos with his thoughts". He recombined in an orderly manner and expressed his personal feelings with personalized brush and ink movements.

However, what kind of person is Wang Shimin besides being a painter?

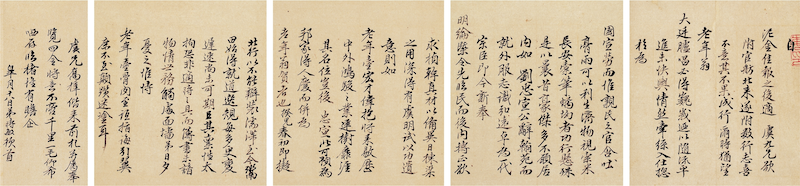

First of all, it should be emphasized that Wang Shimin is a turning point figure in the Taicang Wang family. The Taicang Wang family originated from Taiyuan, Shanxi, and moved south to Jiangzuo. Since the middle of the Ming Dynasty, they have gradually become a prominent family. The great-grandfather Wang Yong (?-1559) managed the family well and the family business rose. The great-grandfather Wang Mengxiang (1515-1582) was a scholar and a writer, and passed on the family business to brothers Wang Xijue (1534-1611) and Wang Dingjue (1536-1585). Wang Xijue was the second place in the imperial examination and later served as the chief minister. Although he did not create any great achievements, his character has always been highly recognized; Wang Dingjue served as the deputy envoy of the Henan Provincial Surveillance Department, but unfortunately died in middle age. Wang Xijue had a son named Wang Heng (1561-1609), who served as an editor in the Hanlin Academy but died in middle age. Wang Dingjue had a son named Wang Shu, who died young. Wang Heng had three sons, Wang Mingyu, Wang Gengyu and Wang Zanyu, but Wang Mingyu and Wang Gengyu died before reaching adulthood. Wang Zanyu changed his name to Shimin at the age of twelve, and the two branches were merged into one, marking a great family mission (Figure 1).

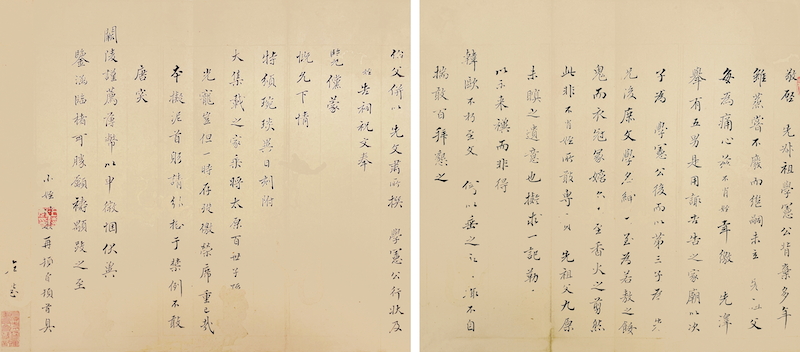

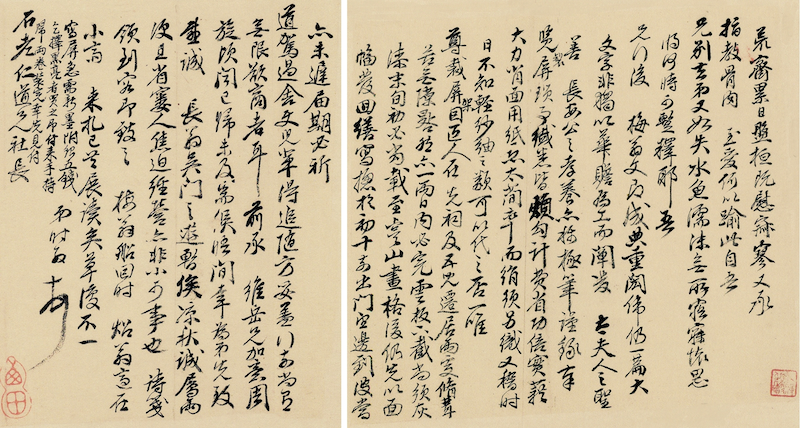

Figure 1 A letter to Chen Jiru in running script on paper, 26cm×20cm

Over the past few years, his two elder brothers died early, and his father and grandfather also passed away when he was eighteen or nineteen. The young Wang Shimin was left alone at a time when his family fortune was in danger. Under the protection of his ancestors, he resolutely entered the officialdom, worked hard in the complicated officialdom, and worked hard to run the Wang family business. In Wang Shimin's view, it was his unshirkable responsibility to make the family prosperous.

My family has had robes and hutongs for three dynasties and two generations of silk and silk. As a son, concerned about the family reputation, how can I bear to accept the family's influence immediately? But I am alone and weak, and I am busy with affairs inside and outside the family. How can I have the time to work hard behind the scenes? Moreover, the world is evil, and if I am not an official, how can I get a chance to marry into a powerful family? I should go to the capital to seek favors as soon as possible.

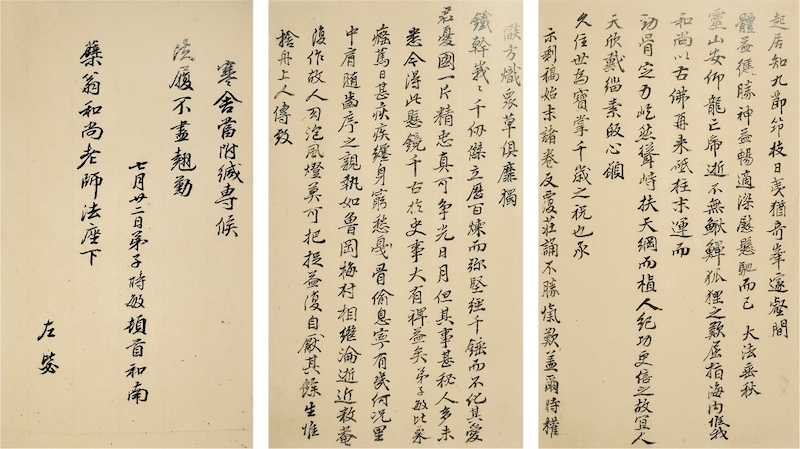

This was the teaching and expectation of his mother, Madam Zhou (1568-1627). He followed her orders and had many children: Wang Ting (1619-1677), Wang Kui (1619-1696), Wang Zhuan (1623-1709), Wang Chi (1627-1658), Wang Yan (1628-1702), Wang Fu (1634-1680), Wang Yu (1635-1699), Wang Yan (1645-1728), and Wang Yi (1646-1704) were born one after another, ensuring the prosperity of the family (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Letter from Fu Ziting, Kui, and Zhuan, dated September 11, 1635, in running script on paper, 28cm×16.5cm

It was this strong sense of family that made Wang Shimin choose the latter between "killing and surrender" after weighing all options when facing the Qing army approaching:

Taichang Gong suffered a rebellion during the reign of Emperor Sizong of the Ming Dynasty. His country was destroyed and his clan temple was reduced to a ruin. The Qing army marched south and was about to reach Taicang. The people of the county fled in panic. Wu Meicun discussed with Taichang Gong: If we refuse, the people will be slaughtered. If we welcome them, we will be unfaithful to the grace of the late emperor. There is no perfect plan. Taichang Gong planned for several days and nights, and also gathered with the county gentry in Minglun Hall. Everyone thought that Taiyuan was an old minister of the Ming Dynasty and had been a nobleman for generations. They all looked to Taichang Gong for their advancement and retreat. Taichang Gong knew that the situation could not be reversed, and wept and said to the crowd: "I am the descendant of a minister, and it is too late to die. The massacre in Jiading is a lesson for the past. I would rather lose one person's integrity to save the people of the whole city." Meicun and others cried loudly, and the sound shook for several miles. The discussion was settled, but the Qing army had already arrived, so he went out of the city with the elders to welcome the surrender. To this day, the West Gate Suspension Bridge is still open, and Yan Gong welcomes the grace.

As Lai Huimin said: "When the regime changes, should the scholars strive for eternal fame for themselves? Or pave a smooth career for their descendants? It is indeed a big choice. But overall, more people choose to surrender to the Qing Dynasty, and fewer choose to become loyalists. That is because gentry played an important role in the family and were related to the prosperity of the entire family." Wang Shimin's choice should have been well considered.

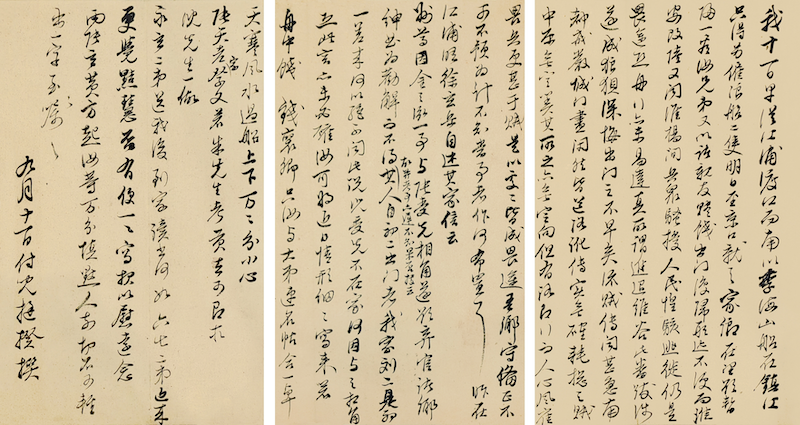

Figure 3 Letter from Fu Ziting to Kui on December 2, 1635, in running script on paper, 28cm×13.1-14.2cm

Later, Wang Shimin was willing to be a remnant of the people, but his sons, who were famous for their literary talent, were eager to take the imperial examinations to advance their careers. He fully supported them and repeatedly wrote letters to those in power to continuously clear the way for his sons to advance their careers (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 4: To Wang Shizhen, cursive script on paper, 13.8cm×12.3cm

In the 12th year of Shunzhi (1655), the second son Wang Kui passed the imperial examination and became a second-class Jinshi; in the 9th year of Kangxi (1670), the eighth son Wang Fan and the eldest grandson Wang Yuanqi (1642-1715) passed the imperial examination together. Later, Wang Fan was selected as a Hanlin Academy scholar, and successively served as ministers of the Ministry of Punishment, the Ministry of Works, the Ministry of War, and the Ministry of Rites, and was promoted to the Grand Secretary of Wenyuan Pavilion; Wang Yuanqi served as the Left Vice Minister of the Ministry of Revenue, and his great-grandson Wang Fu (1670-1756) was successively appointed as the Governor of Guangdong. An old saying in Taicang is: "Two generations of top officials" and "four generations of first-class officials". Wang Shimin realized the earnest expectations of his grandfather and father through various efforts. From then on, the Wang family of Taicang not only had continuous success in the imperial examinations, but also revived the family reputation and continued the family tradition.

Not only that, Wang Shimin himself started it, and his eldest grandson Wang Yuanqi carried it forward, playing with brush and ink, and his descendants continued to accumulate knowledge through words and deeds between fathers and sons, brothers, and teachers and apprentices, creating the "Loudong School of Painting", which has lasted for three hundred years; the four brothers Wang Kui, Wang Zhuan, Wang Yan, and Wang Shuo were proficient in poetry and opera, and were listed as the "Ten Sons of Loudong", forming a prominent family literary and artistic chain group, which can be said to be "the red sash in the art world has outstanding successors, and the green box in the garden has become a family school". As a result, the Taicang Wang family became a typical example of family literary and artistic inheritance in the Ming and Qing Dynasties.

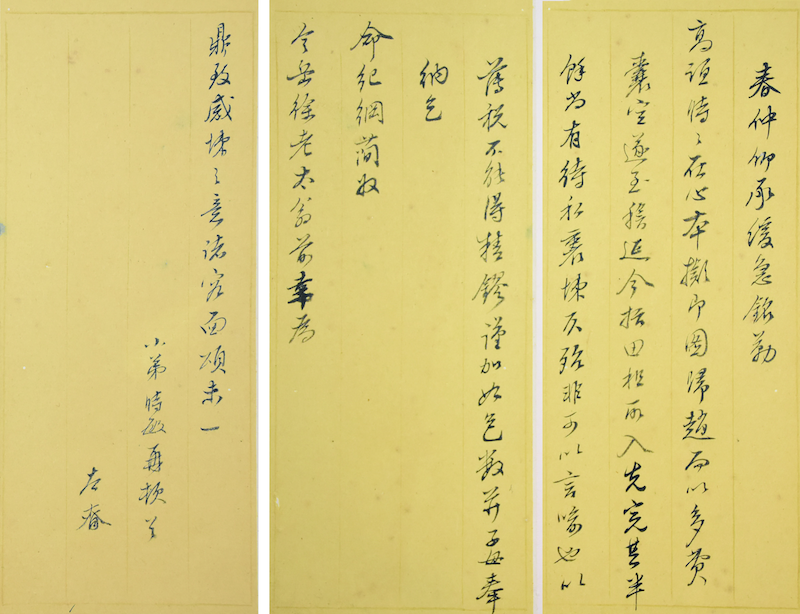

In his later years, Wang Shimin still felt emotional: " I am alone and helpless, facing dangers as heavy as a thousand pounds. My family was weak at the time, and all internal and external affairs were entrusted to me. " Therefore, he always took it as his responsibility to bring honor to the family, worked diligently, and paid tribute to his ancestors, eventually writing a glorious chapter in the family history (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Letter to Xiong Kaiyuan, July 22, 1673, in running script on paper

Over the years, he has cultivated himself and disciplined himself, and repeatedly encouraged his descendants and clan members:

In the 11th year of Chongzhen (1638), there was a letter sent home from Beijing in the year of Wuyin.

In the spring of the fifteenth year of Chongzhen (1642), he wrote "Introduction to the Family Charity Association", urging family members to follow their own wishes and donate money to help the hungry.

In the 14th year of Shunzhi (1657), there was a piece called "The Theory of Teaching the Scholars after the Imperial Examination"; the poem "Instructing Chier" is a five-character ancient poem with 42 rhymes;

In the third year of the reign of Emperor Kangxi (1664), he wrote the "Friendship and Respect Training";

In the seventh year of Kangxi (1668), there was one "Further Instructions" and one "Final Affairs";

In March of the ninth year of the Kangxi reign (1670), he wrote "Family Instructions" to encourage his descendants: be filial and friendly, reflect on your merits and demerits, live in harmony with your neighbors, be self-disciplined and yield, and complete your national duties as soon as possible.

In the tenth year of Emperor Kangxi’s reign (1671), there was an article called “Clan Persuasion”;

In the 12th year of Emperor Kangxi’s reign (1673), he wrote “Respectful Instructions for Later Friends”;

In the 13th year of the reign of Emperor Kangxi (1674), there was a piece called "Instructions to the Three and Two Houses";

In the 14th year of Emperor Kangxi’s reign (1675), he wrote “Handwritten Sayings and Instructions of Ancient Sages in Six Houses”;

In the 15th year of the reign of Emperor Kangxi (1676), there were "Instructions on the Back Building" and "Instructions on Sacrificing to the Fields".

A series of family precepts, later compiled into "Fengchang Family Precepts", fully embodies the principles and norms that Wang Shimin abided by in dealing with the world. When combined with his identity as a "painter", these words seem to easily create a sense of estrangement from reality. People may be surprised: how could Wang Shimin show such a strong sense of moral self-awareness? In the historical context of the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, Wang Shimin had an unimaginable sense of crisis!

It turns out that Wang Shimin, as a head of a family, was not only a painter, but also a poet. When he mourned his deceased wife, he repeatedly blamed himself for "not having achieved anything in writing or in career", and he seemed so worried. In the late Ming Dynasty, he lived in the countryside due to concerns about the officialdom. He did not share the values of a hermit like his father Wang Heng. In the early Qing Dynasty, he always encouraged his descendants to continue their careers with the legacy of his ancestors, and worked hard to maintain the reputation of the family. He also tried to make friends with noble officials to seek support and protection, and enthusiastically participated in local affairs, such as disaster relief, appealing to reed beetles on behalf of officials and people in the region, and initiating the Xiyuan gathering, etc., to preserve the reputation of the gentry, continue the family's reputation, and maintain influence in the local area. And so on. The descendants multiplied, and the family business did not fall. Everything was within the family, and everything was also outside the family!

In his 89 years of life, Wang Shimin traveled extensively, made many friends, and exchanged letters constantly. As a monologue space for personal life, letters were indispensable in people's lives in the past. On the one hand, they told the real stories of interpersonal communication, and on the other hand, they carried the emotional communication between relatives and friends, asking about daily life, reporting the latest situation, telling whereabouts, talking about family affairs, or giving instructions, or improving moral character, or congratulating and condoling, or asking for favors, or discussing knowledge... From military and state affairs to trivial matters in life, they are subtle, specific, and vivid, and have an inestimable value in studying society, history, and culture. Therefore, letters have become a concern, an expectation, and even a continuation, carrying people's rich and profound emotional communication.

Today, there are roughly three aspects of Wang Shimin's letters handed down from generation to generation: First, there are the "letters" collected in "Wang Yanke Xiansheng Collection", which consists of two volumes with a total of 98 letters, most of which are correspondence with officials and old friends. In addition to general greetings, nearly half of them are requests, either for the imperial examinations of their sons and nephews, or for local malpractices, etc., which have become important historical materials for studying Wang Shimin's social interactions, the stories of literati, and the political situation of the Ming and Qing dynasties; second, there are family letters handed down from the fifth year of Kangxi (1666) ) to his fifth son Wang Yan, discussing anecdotes and literary deeds of the time, which were later compiled into a volume of "Xilu Family Letters", which has been widely circulated since it was photocopied in the 32nd year of the reign of Emperor Guangxu (1906); thirdly, Wang Shimin had a close relationship with Wang Hui in his later years, and there were about 30 letters between them, which were reprinted in "Qinghuitang Tongren Letters Collection" in Laiqing Pavilion in the 7th year of Emperor Xianfeng (1857), and were also included in the re-engraved "Qinghui Pavilion Gift Letters" in Deng's Fengyu Tower, most of which were fragments of literary and artistic entertainment. In 2005, seven new handwritten letters from Wang Shimin to Wang Hui appeared in the ancient calligraphy and painting collection circle. Although one or two of them have been included in "Qinghui Pavilion Gift Letters", they are still rare documentary materials. In May 2016, Mr. Mao Xiaoqing collected, sorted and proofread "Wang Shimin Collection", which included all of the above, providing people with a large collection of Wang Shimin's letters.

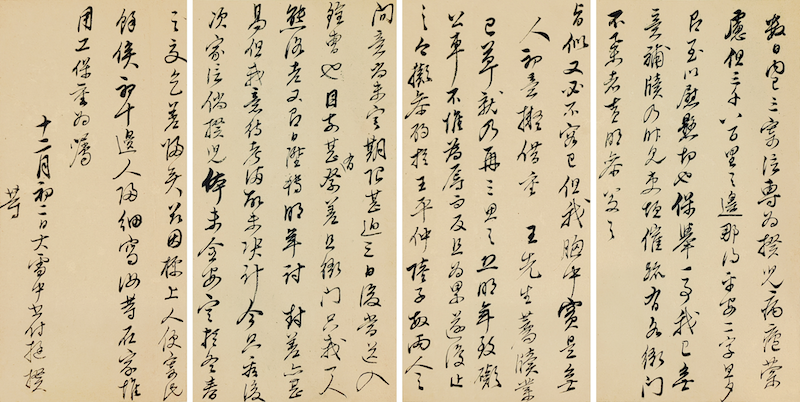

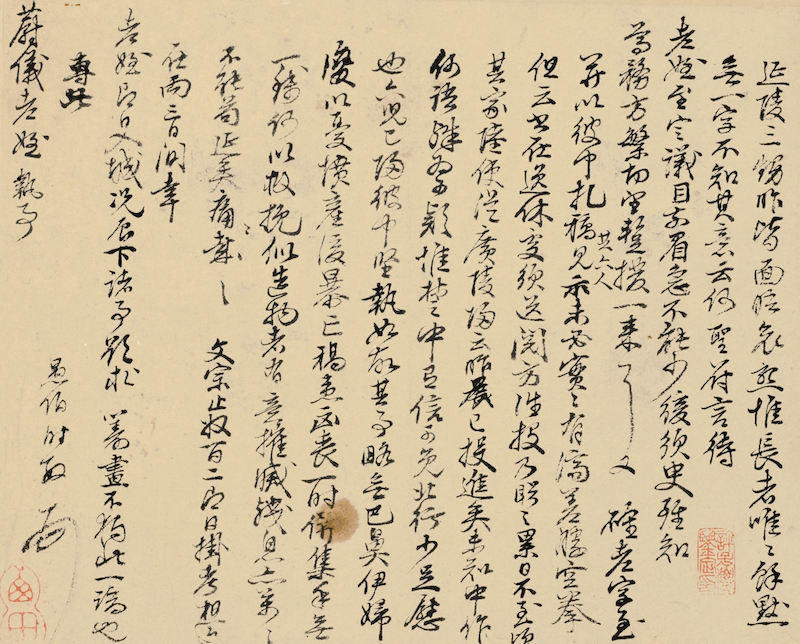

Figure 6 A letter to Qian Zeng in running script on paper, 20.1cm×8cm

As public and private collections continue to be published, the author has continued to pay attention to them in recent years, and has found nearly 90 letters from Wang Shimin, spanning more than 40 years. Among them, there are 34 family letters, which are instructive and instructive, mostly involving family affairs and official anecdotes; there are also 9 letters to his relative Qian Zeng, which mostly describe his journey as an official and frankly talk about the ups and downs (Figure 6); there are also 13 letters to Wang Wenbing, entrusting him with family affairs and property, and explaining everything in detail (Figure 7).

Figure 7 A letter to Wang Wenbing in running script on paper, 27.9cm×34.6cm

There are also several letters to Wu Ting, Wang Ruiguo, Wang Shizhen, Wang Jian, Xiong Kaiyuan, Gu Jianlong, etc., especially nine letters to Wang Hui, which talk about daily art and collection activities in a microscopic and specific, rich and diverse way (Figure 8). As rare textual records, these letters contain a variety of rich information, which naturally become a useful supplement to the "Wang Shimin Collection" and should be valued by researchers who are concerned about Wang Shimin, his art, and even the official career and life of literati in the late Ming and early Qing dynasties.

Figure 8 Letter to Wang Hui, cursive script on paper, 20.7cm×23cm

Therefore, these letters are of great significance for people to understand the social environment and the way of artistic exchange in Wang Shimin's era. Therefore, the author carefully sorted and interpreted them, trying to return to the "historical scene" and restore a more flesh-and-blood "Wang Shimin". By examining the time, place, people and events involved in the letters, those disappeared historical scenes and people's psychology gradually became clear, and the connection between the contents of the letters also made the fragmentary materials more organized.

In this way, Wang Shimin becomes more vivid beyond being a painter.

(The author Wan Xinhua is the deputy director of Jiangsu Art Museum and a member of the Theoretical Committee of the Chinese Artists Association)