The large-scale exhibition "Floating World and Pure Sounds: Art and Culture of Jiangnan in the Late Ming Dynasty" co-organized by the Art Museum of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, the Department of Art and the Shanghai Museum will be exhibited at the Art Museum of the Chinese University of Hong Kong from March 21 to July 20, 2025. The exhibition has been in preparation for many years. It aims to showcase the artistic and cultural features of this unique era, the late Ming Dynasty, from the three levels of material, thought and art, through more than 360 precious collections from a number of art institutions and important individuals at home and abroad. This article is combined with the special exhibition "Floating World and Pure Sounds - Art and Culture of Jiangnan in the Late Ming Dynasty". The author uses the unearthed cultural relics from the Zhu Shoucheng family tomb discovered in Zhujia Lane, Gucun Town, Baoshan District, Shanghai in 1966 as a starting point to explore the relationship between the exquisite handicrafts produced in the late Ming Dynasty and the main livelihood of the citizens at that time, the development of industrial technology, the changes in the material living environment, and the shift in social and cultural concepts.

"In the 15th month of August, the natives and refugees, the families of scholars and officials, female musicians, famous prostitutes, young ladies and beautiful women, boys and catamites, as well as young playboys, idlers and idlers, all gathered in Huqiu. From Shenggong Terrace, Qianren Stone, Crane Stream, Sword Pond, under the Shen Wending Temple, to the Sword Testing Stone and one or two mountain gates, everyone spread out felts and sat on the ground. When you climb up to a height and look at it, it looks like wild geese landing on the flat sand and clouds spreading over the river."

——This is recorded in Volume 5 of "Dreams of Taoan: Mid-Autumn Night at Tiger Hill" written by Zhang Dai in the late Ming Dynasty.

In the mid-sixteenth century, industry and commerce in Jiangnan cities were unprecedentedly prosperous. Especially after the Ming government lifted the maritime ban in the first year of the Longqing reign (1567), China became part of the global maritime trade system at the time. Merchant ships from various countries flocked to China to purchase local products, and a large amount of silver flowed into China from Japan, South America and other places, making major cities in the south of the Yangtze River such as Suzhou, Hangzhou, and Songjiang - production and distribution centers for bulk commodities such as raw silk, silk fabrics, and cotton cloth - more prosperous. At this time, the Jiangnan region not only had an endless supply of local products and novel imported goods, but daily necessities and luxury goods became increasingly refined and elegant. The prosperous city attracted all kinds of people to seek opportunities for livelihood and development. In the early Qing Dynasty, Zhang Dai recalled the Mid-Autumn Night in Suzhou in the late Ming Dynasty, when Tiger Hill was crowded with local and expatriate merchants, scholars, musicians, famous prostitutes, hangers-on, servants, etc. These urban residents with different identities and occupations, also known as "citizens", were the main group living in the prosperous cities of the late Ming Dynasty.

The composition of citizens in Jiangnan during the late Ming Dynasty was complex, and the economic capital, cultural capital, and social status of each person varied greatly. Despite this, there are still two common characteristics among the citizens: First, in terms of political, military, and economic strength, they are far inferior to groups such as nobles, princes, noble relatives, eunuchs, and families of meritorious officials that extend from the imperial power. Due to the lack of royal protection, they had to inevitably make a living on their own or run the family business. However, the responsibility of household management in the Ming Dynasty was often entrusted to women, so scholars often claimed to be "unproductive." Second, after the mid-Ming Dynasty, the imperial court was unable to control social norms, which became increasingly relaxed and class mobility became increasingly common. This social phenomenon has been fully discussed in academia. An individual's social identity, in addition to family background, also depends on the amount of his or her economic and cultural capital. The accumulated cultural capital and social status will in turn affect the economic capital and other social resources (such as connections) that can be obtained in the future. These factors interact with each other. Being eager to develop their own cultural life and social identity is therefore a common characteristic of the citizens of Jiangnan. "The difference between elegance and vulgarity lies in the presence or absence of antiques, so people spare no expense and compete to acquire them" (Wu Qizhen's "Notes on Calligraphy and Painting", Volume 2). Personal artifacts, especially ancient and modern crafts and calligraphy and painting works, are all outward indicators of personal cultural connotation and social identity, and are therefore highly valued. How to make a living, how to use tools, how to establish social status and other issues are closely linked and were the concerns of many citizens in Jiangnan during the late Ming Dynasty.

Fig. 1 Bamboo folding fan with gold-painted red lacquer and figures (Illustration 1.95) Late Ming Dynasty (ca. 1550-1644) Excavated from Zhu Shoucheng’s family tomb in Baoshan District, Shanghai in 1966 Collection of Shanghai Museum

Fig. 1 Bamboo folding fan with gold-painted red lacquer and figures (Illustration 1.95) Late Ming Dynasty (ca. 1550-1644) Excavated from Zhu Shoucheng’s family tomb in Baoshan District, Shanghai in 1966 Collection of Shanghai Museum

The Zhu Shoucheng family tomb was discovered in 1966 at Zhujia Lane, Gucun Town, Baoshan District, Shanghai. There are three coffins in one tomb, and the owners of the tombs are Zhu Shoucheng, his wife Wang and daughter-in-law Yang. Among them, the land purchase certificate belonging to Yang showed that he was buried in the ninth year of Wanli (1581). Most of the important burial objects in the tomb were found in Zhu Shoucheng’s coffin, including a jade-inlaid wooden sword ornament, an incense stick made by the famous Ming Dynasty bamboo carver Zhu Ying, and the most complete set of Ming Dynasty study supplies in existence. The latter two were found on both sides of Shoucheng’s head. In addition, more than 20 folding fans were unearthed from the three coffins, most of which were placed next to the hands of the deceased (Figure 1). Because the burial objects are full of literati flavor and the historical data of the tomb owner's life are missing, commentators have always regarded Zhu Shoucheng as a literati and his burial objects as physical representatives of the exquisite literati culture of the late Ming Dynasty. Until recent years, scholar Liu Zhihua found the epitaph "Epitaph of the Late Friend Zhongbo Zhu Jun" written by Xu Xuemao, a minister of the Jiajing and Wanli dynasties of the Ming Dynasty, for Shoucheng's son Xianqing (Volume 17 of Xu's Haiyu Collection, Collection of Essays), and clarified that Shoucheng was actually a rich farmer rather than a scholar. This changed the previous perception of the owner of this batch of important cultural relics. This discovery also provides a rare opportunity to study the exquisite cultural relics of Jiangnan in the late Ming Dynasty and the material life of the middle class of society at that time.

1. Ways to make a living: Farmland and textiles

Zhu Shoucheng, whose name was Ling and whose nickname was Shoucheng (the epitaph reads "Shoucheng"), was from Zhujiaxiang, Jiading. Shoucheng and his wife Wang had a son named Xianqing, courtesy name Zhongbo, who was born in the second year of Jiajing (1523) and died in February of the second year of Wanli (1574). Xianqing's first wife, Liu, died early, and he had a daughter with his second wife, Yang. According to the words in the epitaph "He mourned for Duke Shoucheng, and although the funeral was solemn, he did not give any cloth to his body", we know that Xianqing was still alive one to two years after his father's death. Therefore, we can infer that Shoucheng died in the sixth year of Longqing (1572) or slightly earlier.

The epitaph says that Shoucheng "started out as a farmer and accumulated considerable wealth", and was a wealthy farmer with strong financial resources. When his son was still young, Shoucheng had already settled in Jiading County and became a neighbor of Xu Xuemo. Xu Xuemo, courtesy name Shuming and alias Taishishanren, was a native of Jiading. He became a Jinshi in the 29th year of Jiajing (1550). Later, he served as an official in Jingzhou, Huguang, and was promoted to the position of Minister of Rites. Xu Xuemo was about the same age as Xianqing. After passing the imperial examination, he left his hometown to become an official. Therefore, he became neighbors with the Zhu family before he passed the imperial examination in the 29th year of Jiajing (1550). The epitaph says "Mr. Shoucheng was a knight-errant man who recruited singers and dancers every day and summoned guests for long drinking nights." The so-called "Renxia" not only refers to the extravagant social habits among urban scholars after the middle period who do not engage in production, spend money to make friends, love drinking, and indulge in pleasure; it also describes the heroic spirit of heroes who are willing to die without hesitation in the face of adversity. The word "Renxia" can't help but remind people of the wooden sword ornament inlaid with jade and cloud pattern unearthed from Zhu Shoucheng's coffin (exhibit). People in the Ming Dynasty said that placing a sword in the study was intended to "have lofty aspirations and courage" (Gao Lian: "Zunsheng Bajian. Yanxianqingshangjian, Volume 2"). However, Xu Xuemo's use of the word "Renxia" does not seem to be a commendatory one. He mentioned Zhu Shoucheng to contrast Xianqing's character with that of a "pure" person who was not tempted by his father's drinking, sex, singing and dancing. Based on this speculation, Zhu Shoucheng should not have any special reputation among the scholars in Jiading.

The people in charge of the city "started out as farmers" and relied on family land to cover expenses and accumulate wealth. The most common way for middle-class families in Ming and Qing dynasties to make a living was to purchase land and collect rent from the land and houses. The literati and connoisseur Li Rihua left officialdom in the 32nd year of the Wanli reign (1604) and lived in seclusion for more than 20 years. His land in Jiaxing was one of his important sources of income. After failing the imperial examinations many times, Yuan Zhongdao considered retiring, also hoping to use the family's land to support his family's living expenses and his own entertainment expenses.

As for what crops were planted on the Zhu family’s farmland, there is no record in the epitaph, but we can make a rough inference by referring to local historical records. After the middle of the Ming Dynasty, the silk and cotton weaving industries developed vigorously, and a large amount of arable land in Jiangnan was converted from growing rice to growing mulberry and cotton. Most of the territories of Hangzhou, Jiaxing and Huzhou prefectures were used to grow mulberry trees, while the arable land in Suzhou and Songjiang prefectures was mostly used to grow cotton. Jiading County in Suzhou Prefecture, where Zhu Shoucheng's family lived, "has a high terrain, which is suitable for growing cotton and is called dry land. Most of the dry land accounts for about 70 to 80 percent, so there are always more people growing flowers and fewer people growing rice. The people occupy land, the rich count it by hectare, the poor count it by mu, and the lowest class rents the land of others and pays the tax, and no one cares about storing grain." (Volume 3 of "Jiajing Jiading County Chronicles"). At the latest during the Jiajing period, cotton had become the main crop in Jiading, and the proportion of cotton planting in the area was the highest in Jiangnan. "The most important goods in the town are cloth and silk. Every household weaves plain cloth," and local people flocked to the cotton cloth industry. Jiading cotton cloth was a famous commodity in the domestic market in the middle and late Ming Dynasty. "Rich merchants stored up and sold it, from Hangzhou, She, Qing, and Ji to Liao, Ji, Shanxi, and Shaanxi, numbering in the tens of thousands." The growing prosperity of the spinning and weaving industries in the Jiangnan region made the cotton industry the main source of wealth for the people of Jiading: "The country's taxes and labor service, the people's food and utensils, and the expenses of health, funerals, and socializing all come from this." Therefore, Zhu Shoucheng's life was probably also supported by the family's cotton planting and spinning.

The textile industry was an important economic pillar of Jiangnan cities in the Ming Dynasty, consisting of two major industries: cotton textile and silk weaving. Around the Hongzhi, Zhengde and Jiajing years, the folk textile industry flourished in major cities such as Suzhou, Hangzhou, Nanjing, as well as in towns and villages in Songjiang, Suzhou, Jiaxing, Huzhou and Hangzhou. After the middle of the Ming Dynasty, sericulture production declined in many parts of the country, except for Jiangnan and Sichuan, where it continued to develop. Later, sericulture production in Jiangnan reached its peak, with the quality being the best in the country. Therefore, the silk weaving industry in Jiangnan had an inherent advantage. By the second half of the 16th century, raw silk, silk fabrics and cotton cloth from Jiangnan had become best-selling commodities in domestic and overseas markets, and the output of cotton cloth and silk goods was extremely large. According to scholars' estimates, the annual output of cotton cloth in the late Ming Dynasty was as high as about 50 million pieces. Although there is a lack of documentary records on the annual output of silk products, the gross output of the Jiangnan silk industry reached 2.03 million taels in the 28th year of the Wanli reign (1600). By the 10th year of the Chongzhen reign (1637), it had risen to 3.37 million taels, with the domestic and foreign markets accounting for 1.2 million and 2.17 million taels respectively (Li Longsheng: "A Study on the Quantity of Overseas Trade in the Late Ming Dynasty - Also on the Impact of the Jiangnan Silk Industry and the Influence of Silver Inflows", pp. 212-213). Exported silk accounts for about 70% of the total value of China's exports, which shows its huge economic value. In the late Ming Dynasty, the export volume of silk and cotton cloth in Jiangnan increased year by year, leading to the influx of huge amounts of silver. The continued prosperity of Jiangnan cities depended on this. The booming textile market has also attracted a large number of rural residents to engage in mulberry and cotton planting, textile deep processing and textile trade industries. "Weaving is not limited to rural areas, but also happens in cities. Village women carry yarn to the market in the morning and exchange it for kapok to take home. The next morning, they carry yarn out again, and they have no time to rest. A weaver usually finishes one piece of yarn in a day, and some even stay up all night. After paying the harvest to the government and interest, the farmers' houses are empty before the end of the year, and they rely entirely on this for food and clothing." (Volume 4 of "Zhengde Songjiang Prefecture Records") Gu Mingshi, the owner of Shanghai Luxiang Garden, the birthplace of Gu embroidery (exhibit), lost his father at an early age, so he "studied with his brother and mother from the loom" (Volume 17 of "Yunjian Zhilue") since he was a child, and relied on his mother's weaving to meet his needs.

Weaving and dyeing technology and the colorful world

The prosperity of the textile industry in the Ming Dynasty provided a large amount of wealth to the south of the Yangtze River; and the advancement of textile technology brought a large number of patterns and colors into urban life. In the fifth year of Hongwu (1372) in the early Ming Dynasty, the imperial court stipulated that "the formal dress of women in the civilian population should be made of purple silk, without gold embroidery, and the robes should be purple, green, pink and other light colors. Bright red, crow blue and yellow are not allowed. Belts should be made of blue silk." In the second year of Tianshun (1458), it was further stipulated that the clothes of officials and civilians should not be made of "black, yellow, purple, dark, black, green, willow yellow, ginger yellow, bright yellow and other colors" (History of Ming Dynasty, Volume 67). It can be seen from the local chronicles of Jiangnan that folk clothing in the early Ming Dynasty was quite simple and the colors were monotonous. As recorded in the "Jiangyin County Annals" of Changzhou Prefecture in the Jiajing period, "In the early days of the country, people's houses were still simple, with three rooms and five frames, and were very small. They wore plain cloth, and the elderly wore long gowns made of purple flowers and flat turbans. When a young man was strolling in the market, he saw a fancy dress, and the people in the market were surprised and made a fuss about it." (Volume 4 of "Jiangyin County Annals") However, with the development of social economy after the mid-Ming Dynasty, people's consumption power increased, and the pursuit of fancy clothes became more and more common. Textile technology also continued to advance under the stimulation of huge demand.

Scholar Fan Jinmin has made an insightful analysis of the improvements in textile technology in Jiangnan during the late Ming Dynasty. For example, the emergence of large-scale slanting looms effectively increased the density of fabrics, facilitating the mass production of flexible, durable, shiny and smooth silk fabrics. Satin fabrics flourished in the Ming and Qing dynasties thanks to this. Another example is the jacquard technique for fabrics. In the late Ming Dynasty, a new method of "picking patterns and tying patterns" was invented. As long as the weavers mastered the jacquard procedure and colored the patterns in sequence, they could weave complex patterns. The pattern book is not only reusable, but can also be replaced multiple times during the weaving process. From then on, fabric patterns no longer had to be repeated, and uniquely designed woven fabrics such as dragon robes and python robes were developed, which could be made by cutting and sewing along the thread.

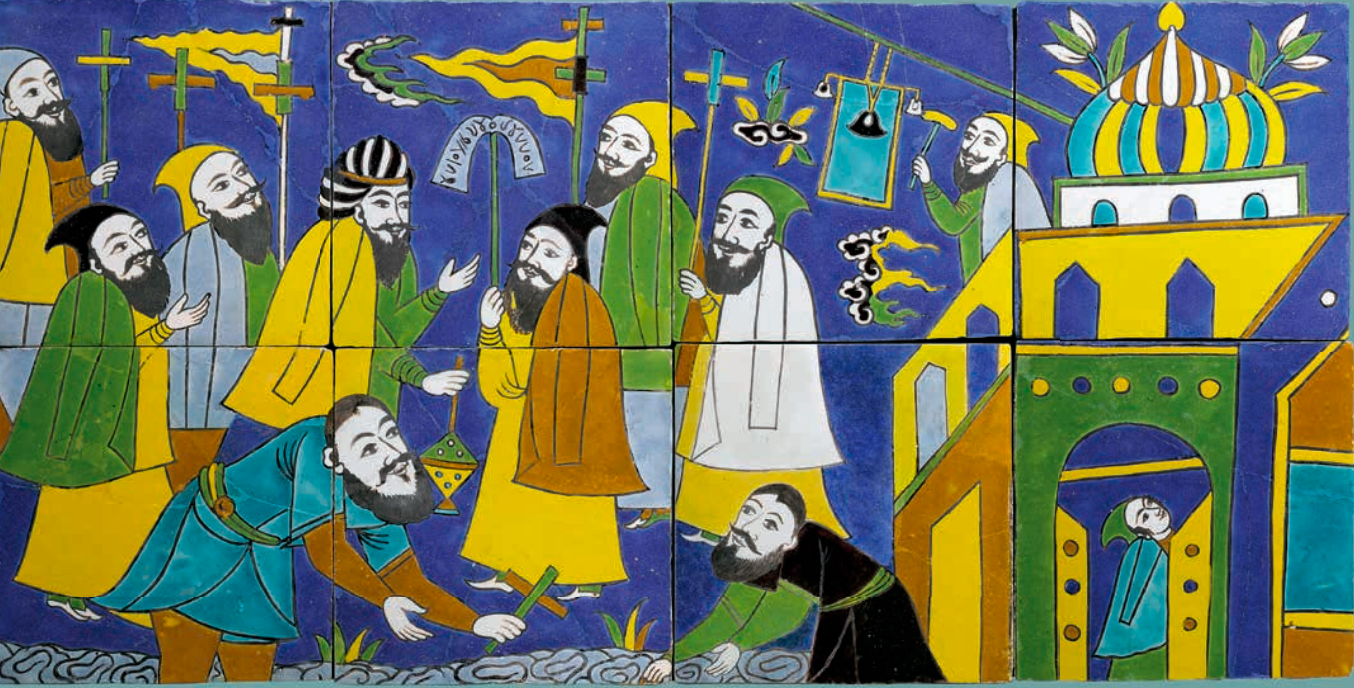

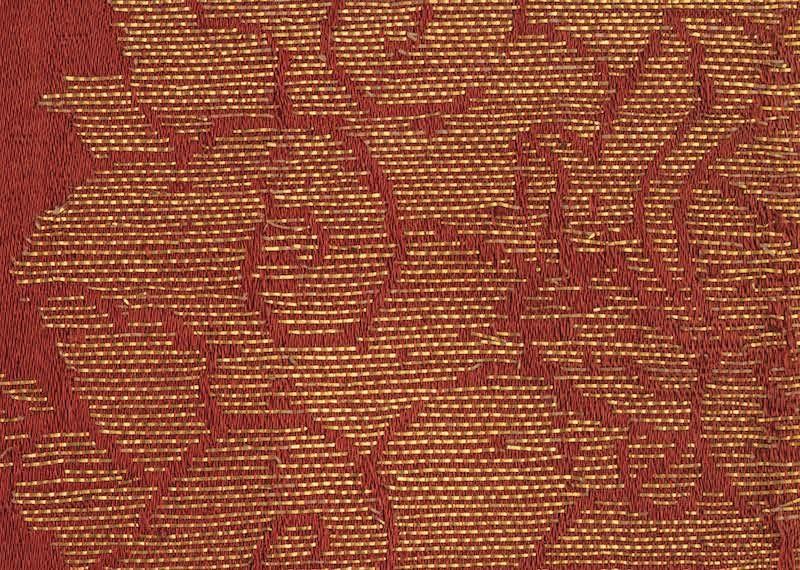

Fig. 2 Song-style brocade with persimmon-red background and four-season flower patterns (Illustration 1.57) Late Ming Dynasty, Hua'e Jiaohuilou Collection

However, the huge impact of advances in weaving and dyeing technology on material life in the late Ming Dynasty is an aspect that has rarely been discussed before. Compared with the simplicity and monotony of the early Ming Dynasty, the weaving and dyeing technology of the late Ming Dynasty brought unprecedented patterns and colors to folk clothing. For example, the zhuanghua technique, which was well developed and extremely popular at the time, used small colored weft tubes to weave in sections within the width of the fabric, breaking through the limitations of color matching of adjacent patterns on the fabric, achieving different colors for each flower and endless variations. This change, thanks to the advanced dyeing technology of the late Ming Dynasty, produced a stronger visual effect. Unlike the early and middle Ming dynasties, when unbleached silk was mostly used, the late Ming dynasty used degummed bleached silk, so it was able to dye bright light colors. Combined with the technology of multiple overdyeing and the increase in the types of mordants, new colors emerged one after another, and the intermediate colors of various levels were particularly rich. (Fan Jinmin: Clothing the World: A Study of the History of Silk in Jiangnan during the Ming and Qing Dynasties) For example, in the gold-embellished satin woven by the Spring Swallows of the Apricot Grove in Figure 1.50, the soft and elegant colors such as light blue and pink were popular in the late Ming Dynasty Wu clothing. According to the literature, scholars have summarized that the colors of Jiangnan silk increased from about 15 or 16 in the early Ming Dynasty to more than 50 in the Jiajing period, and to more than 120 in the late Ming Dynasty. As shown in Catalog 1.57, the tasselled ribbon on the Song-style brocade (Fig. 2) changes into a variety of patterns and colors within a small space, and is woven with twisted silver threads. The variety of patterns and colors is dazzling. The exquisite dyeing technology not only makes the fabrics colorful, but also brings the development of northern and southern embroidery to its peak. Gu embroidery is able to use silk threads to express the varying shades of ink and color. The advancement of silk dyeing technology is a prerequisite for achieving this artistic height.

Figure 3 A satin jacket with small floral patterns and assorted treasures (partial), unearthed from the Ming tomb at Sen Sen Zhuang, Taizhou, Jiangsu, and now in the collection of Taizhou Museum. Quoted from Su Miao: "Ancient Chinese Silk Design Material Picture Series. "Hidden Flower Volume", page 142.

Figure 3 A satin jacket with small floral patterns and assorted treasures (partial), unearthed from the Ming tomb at Sen Sen Zhuang, Taizhou, Jiangsu, and now in the collection of Taizhou Museum. Quoted from Su Miao: "Ancient Chinese Silk Design Material Picture Series. "Hidden Flower Volume", page 142.

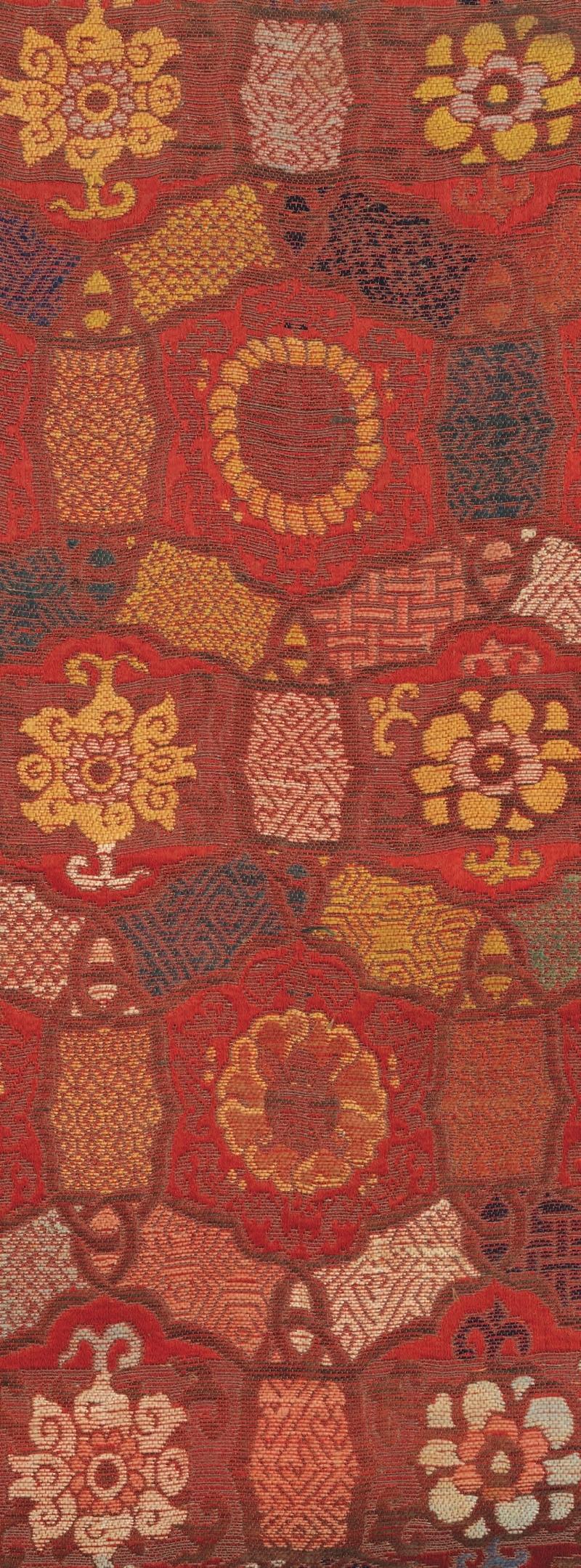

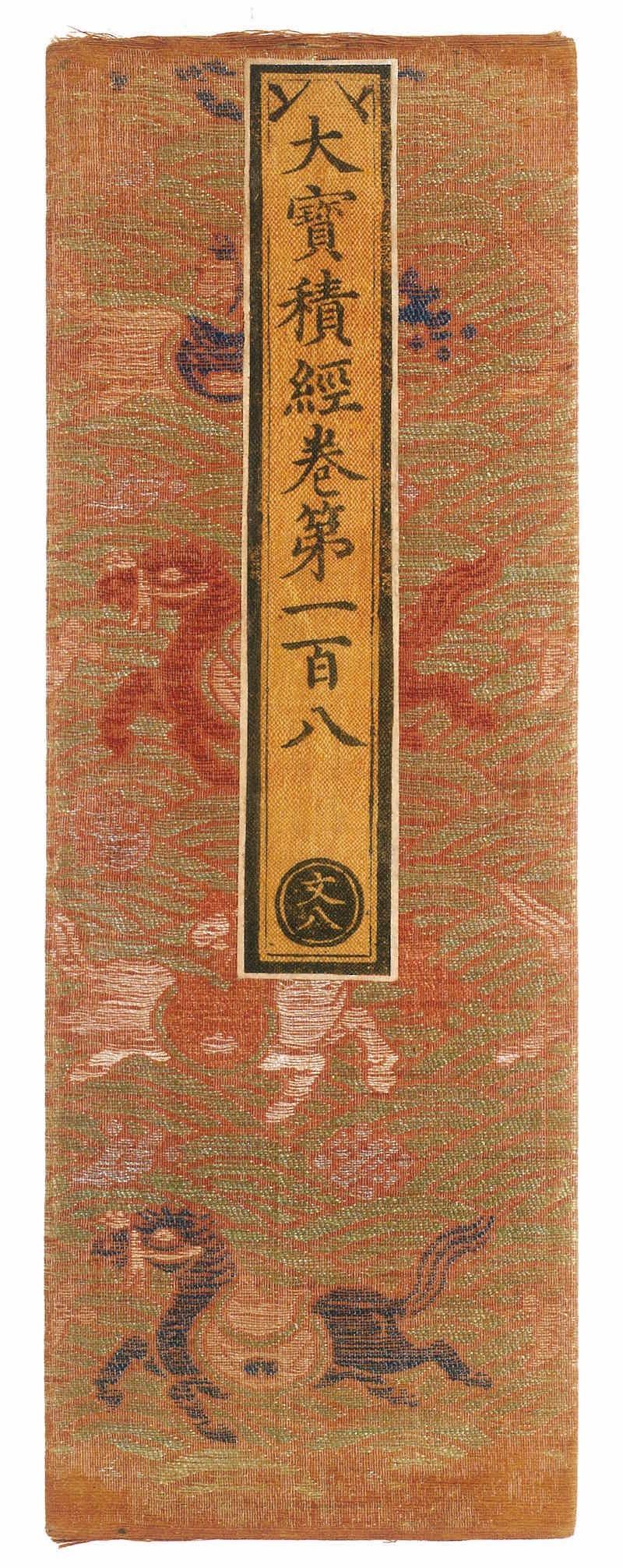

The costumes from the Jiajing and Wanli periods unearthed from tombs in the south of the Yangtze River fully reflect the changes brought about by textile technology and fashion of the time. A large number of clothing made of floral satin, such as tunics, cotton-padded jackets, skirts, pleated skirts, aprons, knee pads, etc., were unearthed from official and civilian tombs of this period, such as the tomb of Xu Fan and his wife in Taizhou, Jiangsu, the tomb of Liu Jian's family, the tomb of Liu Xiang and his wife, the Ming tomb of Sen Sen Zhuang, and the Ming tomb of Li Family in Wangdian, Jiaxing, Zhejiang. Floral satin is woven with two or more colors of weft threads, and has rich layers of color. Although most of the fabrics unearthed by archaeology have lost their color and only the yellow color of the original silk remains (Figure 3), by comparing the silk warp cover of the reprint of "Yongle Beizang" in the late Ming Dynasty preserved in various places, and popular clothing materials such as the damask with falling flowers and flowing water pattern, the damask with curved water pattern, and the damask with various treasures and water waves and horses pattern, we can still imagine how colorful the clothes of the people in Jiangnan at that time were (Figure 4). As for the unearthed gold-woven fabrics, most of them were patches or partial decorations of clothing, such as lapels and hems. Other high-end fabrics, such as brocade silk (Figure 5), brocade gauze, brocade satin, and gold-woven brocade satin are all brightly colored and eye-catching, showing their luxury.

Figure 4: Red ground with various precious stones and water wave horse pattern on the warp surface of the satin. Late Ming Dynasty. Collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, USA.

Figure 5: A compass surface decorated with cloud patterns on a bright red background. Late Ming Dynasty. Collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, USA.

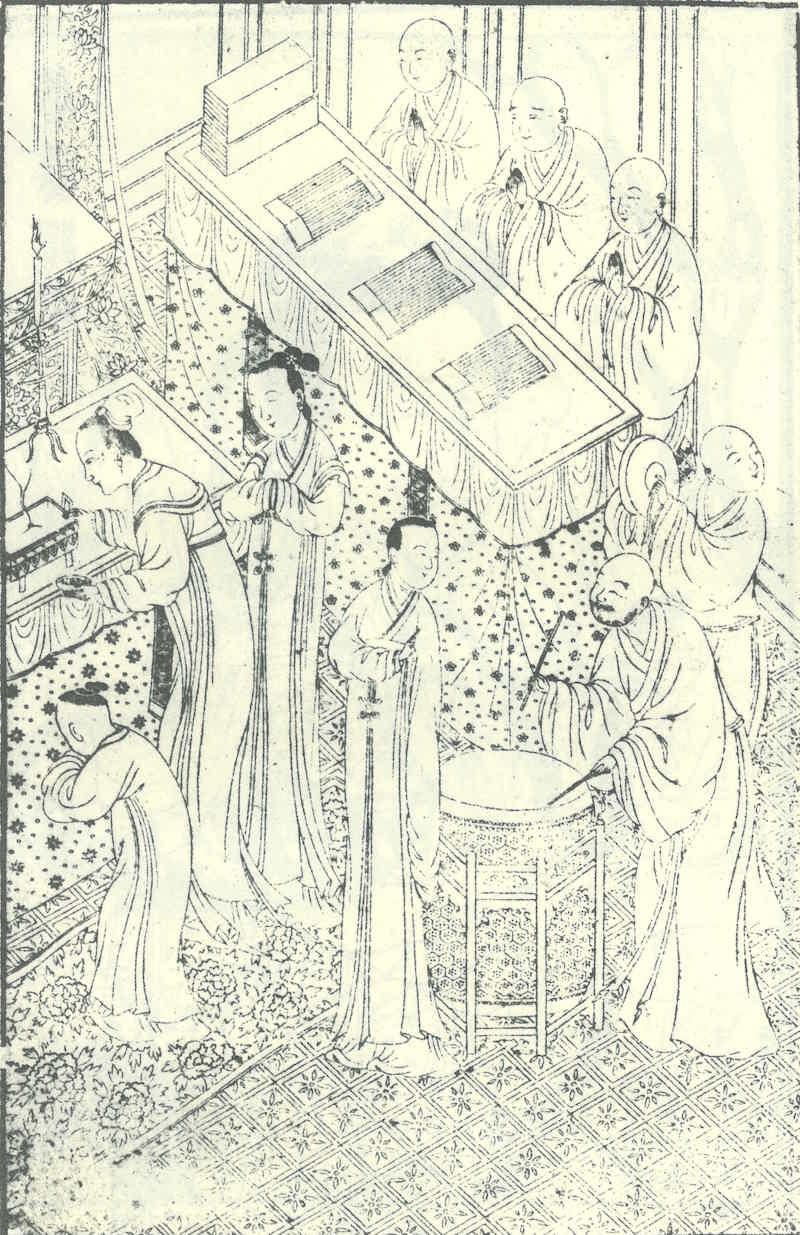

The reason why fabrics had a huge impact on the material living environment in the late Ming Dynasty was that they were not only clothing materials, but also packaging and display materials. For example, gauze is used to make window screens, bedspreads and curtains; satin is used to make bedding; silk brocade is used to wrap objects and mount paintings and calligraphy; brocade is used as tablecloths, chair covers and other interior decorations. The production of these furnishings and utensils involves a wide range of different types of craftsmen using a wide range of flexible fabric applications. In late Ming Dynasty prints, such as the color-printed edition of The Romance of the Western Chamber, engraved by Wu Xing Min Qi in 1640 and housed in the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Köln, Germany, the seventh act, "Breaking the Alliance", and the thirteenth act, "Joining the Party", one can see patterned fabrics used as chair covers, tablecloths, carpets, bedspreads, curtains, sheets, quilts, etc. (Figure 6). There are even more examples of monochrome prints, such as the "Yuanben Chuxiangjibei" (Figure 7) published by Wulin Qifengguan in the 38th year of Wanli (1610), "Yilieji" and "Renjing Yangqiu" published by Huancuitang during the Wanli period. Textiles are almost everywhere in life. These prints depict interior spaces covered with intricate brocade patterns; perhaps their intention was not to depict realism, but to express a typical or ideal material living environment of the late Ming Dynasty. In fact, the patterns, colors and images of fabrics had been largely transformed and appropriated to other materials during the Ming and Qing dynasties. By the second half of the 17th century, examples of interior decoration filled with brocade patterns were common.

Figure 6: "Breaking the Alliance", the seventh act of "Romance of the West Chamber". In the 13th year of Chongzhen (1640), Min Qi Ji of Wuxing engraved a color printed edition. Collection of the Museum of East Asian Art, Cologne, Germany (Inv.-Nr. R 62,1). © Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln, Wald, Sabrina, 2009.02.05, rba_d012779_07

Figure 7 Illustrations from The West Chamber, published by the Yuan Dynasty edition of Wulin Qifengguan in the 38th year of Wanli (1610). Quoted from Zheng Zhenduo, ed., Illustrated History of Chinese Woodblock Printing, Vol. 2, pp. 22-23.

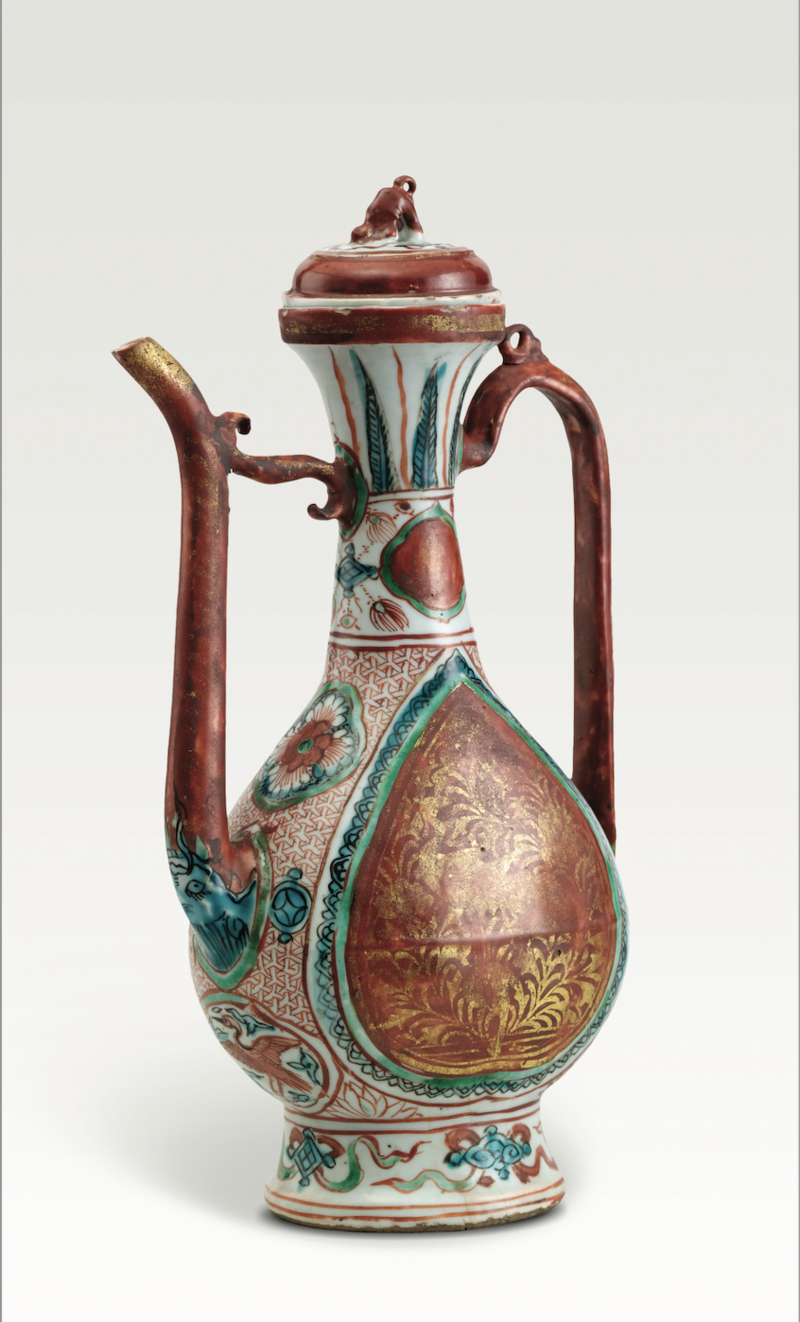

The colors used in Jiangnan fabrics in the late Ming Dynasty could reach ten or more, which is incomparable even to the overglaze colored porcelains of the official kilns at that time. As the diverse colors and patterns of Jiangnan fabrics are increasingly integrated into the living environment of citizens, have the daily utensils and collectibles produced in this environment imitated, appropriated, or even developed decorative strategies to compete with the fabrics? The flow of commodities in the late Ming Dynasty was relatively free, so it was not easy or appropriate for researchers to systematically establish a linear development relationship between commodities during this period. However, it can be seen that the surviving late Ming artifacts made of various materials not only share common decorative themes, such as the five poisonous creatures and the character for longevity, but also have many similarities in overall color matching and pattern selection. For example, the five-color gilt porcelain ewer and the red-ground gold-woven forged porcelain are very similar in color expression (Figs. 8-9); the gilt brocade ground of the Wanli official-style gilt-painted rectangular box is exactly the same as the diamond-shaped swastika and miscellaneous treasure pattern brocade. In addition, in the late Ming Dynasty, folks used the method of mixing paints to create light and bright intermediate colors such as sky blue, snow white, peach red, and pink on lacquerware; colorful inlays of various treasures appeared in the late Ming Dynasty; or even the surfaces of bamboo, hardwood and other objects were decorated with simple plain polishing or uncolored hollow carvings. These techniques and strategies all testify to how craftsmen made full use of the uniqueness of various materials in an era when fabric colors and patterns emerged, responding to aesthetic trends and the cultural labels that society at that time gave to these decorative symbols. The competition among all kinds of craftsmen is a good opportunity for craftsmen and merchants in the city to make a living, get rich and transform their identities. Citizens living in the city with a little wealth have to choose carefully when faced with a wide variety of utensils and even the various cultural symbols contained in the utensils.

Fig. 8 Gold-woven satin with passionflower pattern on a vermilion ground (Fig. 1.45; detail) From the collection of Hua'e Jiaohuilou, mid-late Ming Dynasty

Fig. 9 Five-color gilt-painted pot (Catalogue 1.47) Ming Jiajing (1522-1566) Jiangxi Jingdezhen kiln Shanghai Museum collection

2. Changes in Fashion Items and Cultural Concepts

The Jiading County where Zhu Shoucheng lived experienced significant changes in folk customs and material supplies from the Jiajing period to the Wanli period. These changes are crucial to the interpretation of the artifacts unearthed from the tomb and the development of the ideas of the literati at that time about fashionable items. The Jiading County Annals were compiled four times during the Ming Dynasty. The Annals of Jiading County in the Jiajing period was completed in the 36th year of the Jiajing period (1557). At that time, the city guard should have been between 50 and 60 years old, and his son Xianqing was about 34 years old. The book records the social conditions during the period when the two were active. As for the Wanli Jiading County Annals, it was first compiled in the 32nd year of the Wanli period (1604) and published in the summer of the 33rd year (1605). It was more than 30 years after the death of Zhu and his son. The differences between the two versions of the county annals just reflect the changes in customs during this period.

According to the "Jiading County Annals of the Jiajing Period", the customs of Jiading were originally "simple, ancient, simple and luxuriant". However, since the Hongzhi period, the customs of the people gradually changed: "During the Hongzhi and Zhengde periods, people were accustomed to extravagance and wastefulness, with no sense of frugality. When they held banquets, they would slaughter sheep and beat drums, and they would not complain of being tired of eating for days and nights." The extravagant and wasteful lifestyle during the Hongzhi and Zhengde periods was mainly reflected in the lack of restraint in eating. At that time, the cotton textile industry in Jiading was booming, and the people gradually became wealthy and began to be able to pay attention to the quality of life. By the middle of the Jiajing period, society was becoming increasingly wealthy and its lifestyle more extravagant. Guests were entertained with lavish meals, and weddings and funerals were extremely lavish, with details of arrangement comparable to those of the nobility: "When parents die, funeral music and embroidery are as good as those of princes, and even all property is lost", "Gifts from marriages between men and women are often rare and precious items from afar, with gold, pearls, and silks that illuminate the neighborhood." Regarding the custom of showing off wealth among the people, the compiler of the county annals said frankly: "Alas, the change of customs is not a matter of one day or one night!"

By the time of the Wanli Jiading County Annals, the focus of the shift in customs was on the changes in the "middle people", that is, the behavioral changes of middle-class families. For example, when hosting a banquet, the wealthy would serve delicacies from land and sea far away. "Even the middle class would imitate them, and the cost of one banquet would often consume several months' worth of food." In order to imitate the rich, middle-class families would not hesitate to spend several months' worth of food on hosting guests. At the same time, people became more utilitarian. Not only would servants in wealthy families turn a blind eye to their master's family when they saw it decline, "as for the middle-class families, who were raised with kindness, or even the eldest son and grandson were raised, if they rebelled, they would be beaten and scolded at will, and even brought into the house with weapons." Disobedience between the old and the young occurred from time to time. Social morality also showed signs of collapse. We occasionally heard of such evil deeds as willful framing, false accusations, ganging up on others, encroaching on land, and robbing villagers of their cotton. The last of the vices listed in the county annals is the extravagant lifestyle of the lower classes of society: "The restaurants are grand, with all kinds of delicacies, accompaniment by singing and dancing. The child slaves of the wealthy families and the servants in the government offices eat to their heart's content. When they are full, they donate gold to make a tablet. The diners laugh and laugh, while the masters are heartbroken." The child slaves and servants of the lower classes of society drink and eat delicacies from land and sea, and spend money extravagantly. Such evil customs were not recorded in previous chronicles. The compiler could not help but sigh: "The people cannot live in peace and contentment in a peaceful world, but obey slander and seek evil, and kill the people themselves. What kind of heart is this!"

In the 16th century, Jiading County experienced an evolution from prosperity to luxury and extravagance, and finally to a society where the culture of extravagance and wastefulness permeated the middle and lower classes. Faced with these changes, the compilers of the "Wanli Jiading County Annals" - Zhang Yingwu, Zheng Yinji, Tang Shisheng, Lou Jian, Li Liufang and others - all made severe criticisms. The above-mentioned compilers were all famous scholars during the Jiajing and Wanli periods. They advocated the use of ancient learning to counter the popular learning of the time. The latter three together with Cheng Jiasui were collectively known as the "Four Masters of Jiading", and were famous throughout the country for their poetry, calligraphy and painting. Their views were extremely representative among the literati in Jiangnan during the late Ming Dynasty. They were saddened by the social disorder and listed the excessive extravagance and class transcendence of the lower classes as the worst bad habits. This shows how disgusted the literati were in the early seventeenth century.

From the middle and late Jiajing period to the end of the Ming Dynasty, with the changes in social customs and material living environment, the evaluation of objects made of different materials and with different decorations continued to change. The literati's disgust with the above-mentioned bad habits was also projected onto the materials and decorations that some people used to show off their wealth.

Back to the cultural relics unearthed from Zhu Shoucheng's coffin, there are four main categories: one, stationery, incense sticks and sword ornaments; two, folding fans; three, personal clothing and small accessories; four, funeral supplies including combs and bronze mirrors. Compared with other Ming tombs in Shanghai, the third and fourth categories are typical burial objects. The first and second categories are not typical burial objects, but seem to be the favorite things of the tomb owner during his lifetime. The materials, shapes and decorations of these two types of cultural relics, including the use of hardwood, the craftsman's name, and the antique and colorful decorations such as inlaid silver wire and painted bamboo frames, were all fashionable from the late Jiajing period to the Longqing period, and the popularity of these craft features continued until the end of the Ming Dynasty. Observing these characteristics reveals the change in the concept of "things" during the late Ming Dynasty (70 to 80 years).

From rosewood writing desk to red tassel incense tube

Among the artifacts unearthed from Zhu Shoucheng’s tomb, the most eye-catching are stationery items (Figure 10), nine of which are made of rosewood. The mass production and sale of rosewood furniture began among the Chinese people in the second half of the 16th century. Fan Lian, who was born in the 19th year of the Jiajing reign (1540), wrote in Volume 2 of Yunjian Jumuchao, which was completed around the 21st year of the Wanli reign (1593): "As for fine wooden furniture, such as desks and Zen chairs, I have never seen them in my youth. Ordinary people only use square tables with ginkgo and gold lacquer. Since Mo Tinghan and the two young masters Gu and Song, they have used several pieces of fine wood, which were also purchased from Wumen. Since the Longlong and Wanli reigns, even the families of slaves and fastmen have used fine furniture, and small carpenters in Huizhou have set up shops in the county seat, and even dowry items are included in their shops." When Fan Lian was young, the people of Songjiang only used "square tables with ginkgo and gold lacquer". From this, we can know that before the end of the Jiajing reign, even if hardwood furniture was circulated in Jiangnan, only wealthy families would purchase it in small quantities from Suzhou. During the reigns of Emperors Longqing and Wanli, exquisite hardwood furniture began to become popular among the people. Fan Lian's observation is consistent with the fact that no hardwood furniture such as red sandalwood and huanghuali was mentioned among the more than 8,000 pieces of furniture confiscated by the powerful official Yan Song in the 43rd year of Jiajing (1564). It also proves the popular period of red sandalwood stationery in Jiangnan. Wang Shixing wrote Guangzhiyi in the 25th year of Wanli (1597), discussing the popular style of wooden products at that time: "For example, study accessories, desks, and beds are now mostly made of red sandalwood and rosewood. They prefer simplicity to carvings. Even if there are carvings, they are all in the styles of Shang, Zhou, Qin, and Han dynasties. All remote areas in China and abroad follow suit, and this trend began to flourish during the Jiaqing, Longqing, and Wanli dynasties." Red sandalwood stationery and furniture became popular in the second half of the 16th century. There are two main reasons for this: first, the continuous improvement of private consumption power; second, the lifting of the maritime ban during the Longqing period, and red sandalwood originating from India could be imported in large quantities via ocean-going cargo ships.

Figure 10 Stationery unearthed from Zhu Shoucheng’s family tomb, now in the collection of the Shanghai Museum.

Gao Lian's "Zunsheng Bajian" was completed in the 19th year of the Wanli reign (1591), which was also completed in the last decade of the 16th century, along with "Yunjian Jumuchao" and "Guangzhiyi". In his book, Gao Lian praised the stationery and ornaments made of red sandalwood. He commented on rosewood's rosary beads, fan handles, pen holders, pressure rulers, book cases, pen boats and small tables as "elegant", "beautiful", "excellent", "superior", "very exquisite", "a fine item to be handed down from generation to generation", and "very pleasing to the eye". In addition, ancient research boxes, secret chambers and ink boxes were also commonly seen. Only when rosewood was used to make musical instruments was it questioned, "What is the point of its beauty?" This shows that by the end of the 16th century, red sandalwood was still a fine material in the eyes of literati. In the 26th year of the Wanli reign (1598), Tang Xianzu wrote the section "The Return of the Soul in the Peony Pavilion - Nao Shang", in which he specifically describes how Du Liniang ordered her maid Chunxiang to store her self-portrait in a "red sandalwood box" and hide it under a Taihu stone. In the 37th year of the Wanli reign (1609), Li Rihua, who was retiring in Jiaxing, still collected a red sandalwood chime stone for fun (Volume 1 of Weishuixuan Diary).

When red sandalwood became popular among the middle and lower classes of society, voices disparaging it as "vulgar" began to emerge in the early seventeenth century, and became even more serious during the Tianqi and Chongzhen periods. In the Wanli Yewaibian written by Shen Defu in Jiaxing, Zhejiang Province in the 34th year of the Wanli reign (1606) and the 47th year of the Wanli reign (1619), it is pointed out that "nowadays, all folding fans made of rosewood, ivory, and ebony in Wuzhong are considered to be customary." Wen Zhenheng's "Changwuzhi" was written a little later, between the first year of the Tianqi reign (1621) and the tenth year of the Chongzhen reign (1637). The book lists more fashionable red sandalwood items, such as scroll bodies, scaffolding stoves, carved pen tubes, combs, etc., all of which were denounced by the author as things that are not suitable for scholars to use; the carved secret cabinets, fan handles, research boxes, book boxes, and stationery boxes that Gao Lian previously believed were suitable for making with red sandalwood were also evaluated as vulgar items. Only a few items such as rulers, pen boats, pen holders, tripod-style stove covers, and old-style wooden couches were allowed to be made of red sandalwood. From Gao Lian to Shen Defu and Wen Zhenheng, the evaluation of red sandalwood changed dramatically over the decades, showing how the appreciation of artifacts by late Ming literati changed with the times. Wen Zhenheng's disparagement of certain materials and types of vessels was not only intended to maintain the cultural authority of the literati in judging elegance and vulgarity, but was also likely an unintentional or intentional projection of the "bad habits" of the middle and lower class citizens, who were overspending and transcending their class boundaries, onto the "abused" materials and vessels. In this regard, his comments are no different from those of the compiler of the Wanli Jiading County Annals, who criticized the child slaves of wealthy families and servants in government offices for being too greedy for delicacies from land and sea.

Looking at the evolution of the attitudes of late Ming scholars toward red sandalwood artifacts, and considering that the stationery found in Zhu Shoucheng’s tomb was produced before the sixth year of the Longqing reign (1572), it can be inferred that the scholars’ evaluation of them at the time was quite positive, closer to Gao Lian’s view than Wen Zhenheng’s. These stationery items were the leading fashion products at the time. Not only were their materials novel, but their decorative style, which was also popular in late Ming culture, was also antique and eccentric. For example, the inlaid silver wire decorations seen on wooden bottles with embossed dragon patterns, wooden seal boxes with pine and crane patterns, and wooden boxes with pictures of foreigners playing with lions are characteristics of Xia Dynasty bronzes as recognized by Ming people, and were used to express the ancient style. Another example is inlaying Song Dynasty jade ornaments on a wooden ruler, turning collected antiques into new objects. Although the folk love of antiques in the late Ming Dynasty lacked a basis in rigorous research, they relied on their rich creativity and reference to antiques and books such as "Bogutu" to create a variety of antique-like and simulated shapes and decorations, and applied them to objects of different materials such as copper, porcelain, and jade. As the trend developed, the objects of imitation of antiques also expanded from ancient bronze and jade to porcelain from the Song, Yuan and current dynasties. In addition to ancient artifacts, it was also popular in the late Ming Dynasty to cleverly change the traditional official script to create "strange characters", using the strange as the ancient.

The artistic characteristics of the late Ming Dynasty, which valued the strange and the unusual, were particularly prominent in the folding fans unearthed from the tomb of Zhu Shoucheng's family. More than 20 folding fans were unearthed from the tomb. Compared with most tombs which only had one folding fan, and a small number of tombs which had two to four folding fans, this number is unique in the country. Among these folding fans, there are fans with calligraphy and painting in gold dust, which have been popular among literati since the 15th century, and there are also fans with gold paper sprinkled with geometric gold flakes (Figure 1). The latter was already in circulation in the south by the mid-sixteenth century at the latest. Although the decorative styles are different, the more than 20 folding fans are all golden, with the "gold and silver coating" style of Japanese folding fans that the Ming people knew. The most novel thing about these folding fans is the decoration on the black lacquered ribs: some of the ribs have crabapple-shaped openings on both the front and back, with pictures of scholars on a picnic and admiring the lotus inside; some are painted with pictures of people carrying a zither to visit friends, or peonies and longevity birds, using colorful lacquer and gold painting; some have "The Memorial to the Emperor Before Departure" written in tiny gold calligraphy. There are not many unearthed examples of similar fan bone paintings or calligraphy, and there is no documentation, so there is no way of knowing how popular they were at the time. This kind of decoration brings the density of the color pattern of the folding fan to the extreme, which echoes the characteristics of late Ming fabrics discussed in the previous section. It is a decorative technique with unique characteristics of the times.

Looking at the stationery and folding fans in Zhu Shoucheng's tomb, the materials and decorative styles mostly come from all over the world. For example, the dustpan-shaped Duan inkstone comes from Zhaoqing, Guangdong, red sandalwood comes from India, and huanghuali wood comes from Hainan. The gold and silver coatings mentioned in the previous paragraph are the Japanese decorative style as recognized by the Ming people; objects such as "Japanese lacquer" and "Japanese copper stove" that also emphasize gold decoration have also been highly praised in literati's appreciation books since the late 16th century. In addition, rhino horn was also an imported material sought after by wealthy families in the late Ming Dynasty. It was transported to China by ocean-going merchant ships passing through Sumatra, Java, India and other Asian rhino origins. After being skillfully carved, it was made into various rhino cups, some in the shape of flowers and leaves, and some imitating the shapes of ancient bronzes. It became a popular commodity and was imitated by the Dehua porcelain kilns in Fujian. These raw materials were not first imported into China in the late Ming Dynasty. However, it was precisely because the pirate raids that had plagued the southeastern coast for many years gradually subsided from the end of the Jiajing period to the beginning of the Longqing period, and the maritime ban was lifted, that high-end raw materials from home and abroad gathered in the south of the Yangtze River, and exquisite handicrafts were mass-produced, that middle-class families in the city had the opportunity to appreciate and play with them.

After the mid-Ming Dynasty, most craftsmen registered as imperial craftsmen (shift craftsmen) could pay silver instead of serving in the capital regularly, increasing their freedom at work. Some of them moved to the economically prosperous Jiangnan region in the 16th century and settled there, focusing on developing handicrafts and actively cultivating their children to study and take imperial examinations in order to change their hereditary status as craftsmen. Zhu Ying, the maker of the bamboo carved incense tube unearthed from Zhu Shoucheng's tomb, is a famous example. Zhu Ying, whose courtesy name is Qingfu and whose pseudonym is Xiaosongshanren, is the son of the famous sculptor Zhu He. Zhu He and his family moved from Huating, Jiangsu to Jiading during the Zhengde and early Jiajing periods, when Jiading's economy was booming. Zhu Ying inherited his father's business and became famous for his openwork works. His reputation spread beyond the south of the Yangtze River and even spread to places like Henan. Because Zhu Ying had a calm personality and was skilled in calligraphy, poetry and painting, the gentry of Jiading highly respected him and left behind many accurate records of his life and works.

Figure 11: Ming Dynasty red tassel bamboo carving of Liu Ruan on the Tiantai incense burner. Unearthed from the Zhu Shoucheng family tomb in Baoshan District, Shanghai. Collection of Shanghai Museum.

Figure 11: Ming Dynasty red tassel bamboo carving of Liu Ruan on the Tiantai incense burner. Unearthed from the Zhu Shoucheng family tomb in Baoshan District, Shanghai. Collection of Shanghai Museum.

The bamboo carving of Liu Ruan Ru Tiantai incense burner unearthed from the Zhu Shoucheng family tomb is engraved with "Zhu Ying" and his nickname "Xiaosong" (Figure 11). The signature is one of the bases for identifying bamboo-carved round-carved toads and other red tassel works handed down from generation to generation. It was a fashion in the late Ming Dynasty to engrave the names of craftsmen on handicrafts. On the one hand, this phenomenon shows that the social status of craftsmen at that time had improved, "some of them even sat with the gentry" (Wang Shizhen: "Gu Bu Gu Lu"), and famous craftsmen were respected, so things were valuable because of the people who made them. On the other hand, the name mark as the maker's personal imprint was left on the work, just like the year mark on Ming Dynasty official kiln porcelain, which represented the maker's recognition of the quality of the product and was used to identify it. So far, we have seen that there are many craftsmen who left their names on late Ming Dynasty artifacts, such as the famous jade craftsman Lu Zigang, Zhou Zhu, who was famous for inlaying various treasures, Hu Wenming, a famous bronze caster, and Jiang Qianli, who was good at making inlaid mother-of-pearl lacquerware. However, unlike Zhu Ying, although most Jiangnan craftsmen were famous and their works were sold all over the country, there is very little information about their lives. Most of them are only sporadic records written at a time when counterfeit artifacts were increasing. The commodity market in the late Ming Dynasty was flooded with counterfeits. Although leaving names on objects did not help to distinguish their authenticity, it was a convenient solution to satisfy consumers from all over the world's pursuit of famous artists' works.

Wang Shizhen's "Gu Bu Gu Lu" records: "Paintings used to be valued in the Song Dynasty, but in the past 30 years, the Yuan Dynasty has suddenly become popular, even Ni Yuanzhen and Ming Shen Zhou, and their prices have increased tenfold; kiln ware used to be valued in the Ge and Ru dynasties, but in the past 15 years, the Xuande period has suddenly become popular, even Yongle and Chenghua, and their prices have also increased tenfold. Most of them were started by people from Wu, and followed by people from Huizhou, which is strange. Today, the jade crafted by Lu Zigang in Wu, the rhinoceros horn crafted by Bao Tiancheng, the silver crafted by Zhu Bishan, the tin crafted by Zhao Liangbi, the fan crafted by Ma Xun, the Shang Dynasty inlay crafted by Zhou Zhi, and the gold crafted by Lu Aishan in She, the agate crafted by Wang Xiaoxi, and the bronze crafted by Jiang Baoyun, all cost twice the usual price, and some of them even sit with the gentry. Recently, I heard that this hobby has flowed into the palace, and the trend has not stopped." "Gu Bu Gu Lu" was written around the 12th year of the Wanli reign (1584). According to this calculation, the sharp rise in the prices of Yuan and Ming paintings and calligraphy began in the 33rd year of Jiajing (1554), while the rise in the prices of official kiln porcelain of this dynasty began around the 3rd year of Longqing (1569). According to "After Writing the Epitaph of Zhu Qingfu" written by Qiu Ji, his relative Yin Zhonghong once "used one tael of white gold to purchase the sandalwood statue of Lu Chunyang carved by him" (Volume 20 of "Wanli Jiading County Chronicles"). Xu Xuemo once said in "Epitaph of Zhu Yinjun" that in the seventeen years between the death of his wife and his own death, Zhu Ying "abandoned most of the carving that he was good at." Based on this, it is estimated that Yin Zhonghong's purchase of the portrait of Lu Chunyang carved by Zhu Ying must have occurred between the 39th year of Jiajing and the 4th year of Longqing (1560-1570). At this time, Zhu Ying's works could still be purchased. One statue was worth one liang, or 24 taels of silver, which was equal to two years' salary of a teacher at the time as recorded in the "Jiajing Jiading County Annals" (12 taels of silver per year). If this is the case, the bamboo incense tube with red tassel pattern unearthed from Zhu Shoucheng's coffin should also be valuable, but it is not yet a priceless treasure as described in the "Wanli Jiading County Annals" in the early 17th century as "treasured by the world and almost unobtainable." The owner of the tomb probably could not have imagined how Zhu Ying's bamboo carved incense tube would have changed in people's minds in the fifty years after the Longqing Dynasty.

3. Summary

During the seventy or eighty years from the mid-to-late sixteenth century to the fall of the Ming Dynasty, the economic structure, industrial technology, material living environment, social customs, and even cultural concepts of Jiangnan cities all underwent many changes, and each aspect was closely linked and influenced each other. Jiading County, discussed in this article, can be regarded as a representative of the Jiangnan cities at that time. In the early late Ming Dynasty, Zhu Shoucheng, as a wealthy peasant, relied on the wealth he gained from his land to buy his favorite fashionable items and enjoy the rich material life brought about by the prosperous economy, developed handicrafts, and the gathering of domestic and foreign goods in the south of the Yangtze River. He could enjoy the exquisite study and writing utensils that were almost monopolized by literati in the past, wear colorful embroidered clothes that were originally only used by royal aristocrats, and hold a gold-sprinkled folding fan in his hand, just like a talented and famous scholar, without having to endure the fierce criticism from the literati group and the urgent fear that the Ming Dynasty was in danger. Many middle-class urban citizens like Zhu Shoucheng enjoyed unprecedented material and spiritual freedom. For them, this was a golden age for Jiangnan.

Zhu Shoucheng was a wealthy farmer who owned many utensils unearthed from the tomb. Some literati commented that they were "vulgar items" and "abuse", while today's scholars may regard them as the result of "luxury consumption" and "social imitation trend". This kind of consumption pattern should be very common in late Ming society. The reason why Zhu Shoucheng's family tomb is particularly eye-catching is that similar luxury items were rarely placed in the tombs of ordinary people in the Ming Dynasty. However, was this Zhu Shoucheng’s choice? The Epitaph of My Late Friend Zhongbo Zhu Jun records that his son Xianqing was once a student of the county school. Although he failed in the imperial examinations in Beijing many times, "his reputation for literature rose high, and the outstanding scholars in Wuzhong vied with each other to associate with him." His learning was highly respected by the scholars in Wuzhong. "Wherever he went, he carried ancient books and utensils with him, and accompanied them with wine and poetry, and lingered happily, as if he was in a graceful manner." Moreover, "in his daily life, he wore quite elegant clothes." Wherever Zhu Xianqing went, he would always have ancient books and maps, ancient ritual vessels, compose poetry and drink wine, and was a man of great literary talent. He also dressed quite gorgeously on weekdays. All these descriptions show that Zhu Xianqing had already joined the group of scholars. One can't help but wonder whether the exquisite stationery, incense burners and folding fans buried with his father were because Xianqing wanted to portray his father as a literati? There is no definite answer to this question. In the late Ming Dynasty, the consumer market was relatively open, economic resources flowed to all social classes, knowledge of refined living became popular, and the relationship between each class and the material life they possessed was intricate. Perhaps, it was the richness and complexity of the material and cultural life in the Jiangnan cities in the late Ming Dynasty that made all of this a beautiful memory that the Ming loyalists in the early Qing Dynasty lingered in their dreams.

(The author is an associate professor at the Department of Fine Arts at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. This article is included in the catalogue "Floating World Pure Sounds: Art and Culture in Jiangnan during the Late Ming Dynasty", the original title of which is "Prosperity Everywhere: The Life of Middle-Class Citizens in Jiangnan Cities during the Late Ming Dynasty")