Art historian Wu Hung's "Chinese Painting" series has recently reached its finale - "Chinese Painting: Yuan to Qing". This article is an excerpt from the section "Paintings by the Survivors" in the book. The dynasty change between the Ming and Qing dynasties created the most profound and artistic paintings by the survivors in the history of Chinese art. The alternation between the Ming and Qing dynasties was not an ordinary change of dynasty. The "hair-cutting order" issued by the Manchu conquerors was not only an insult to individuals, but also meant the surrender of the entire nation. Therefore, the paintings by the survivors in the early Qing Dynasty far exceeded their Yuan Dynasty predecessors in terms of quantity and ideological depth. At this time, "painting" took on the functions of "expressing one's will" and "singing words", providing these people with a channel to express their ambitions and temperament.

Book cover of Chinese Painting: Yuan to Qing Dynasty

The number and thought depth of the paintings by the loyalists in the early Qing Dynasty far exceeded that of their Yuan Dynasty predecessors. One important reason was a deeper pain: for the Han literati in the early Qing Dynasty who regarded themselves as loyalists, the transition from Ming to Qing was not an ordinary change of dynasty. What hurt them most was the "hair-cutting order" issued by the Qing army after it marched into Jiangnan, which was enforced by barbaric means of "keeping the head but not the hair, keeping the hair but not the head". Chinese culture has always advocated filial piety. The "Book of Filial Piety" teaches that "the body, hair and skin are received from parents, and one should not dare to damage them. This is the beginning of filial piety." The Manchu conquerors forced all Han men to shave their hair on the front of their heads and braid their hair behind their heads. This was not only an insult to the individual, but also meant the submission of the entire nation. Some fierce loyalists participated in anti-Qing activities and continued to fight with their pens after the struggle failed; others adopted a non-cooperative attitude, either living in seclusion in the mountains or becoming reclusive monks and Taoists. Chinese culture has always emphasized that "poetry expresses one's aspirations and songs sing one's words". The basic reason for the flourishing of painting by the loyalists is that "painting" at this time took on the functions of "expressing one's aspirations" and "singing one's words", providing these people with a channel to express their aspirations and temperament.

Xiang Shengmo and Zhang Qi, "Self-portrait of Vermilion Landscape", Qing Dynasty, Collection of Stone Book House, Taipei

For poets and painters loyal to the Ming dynasty, the fall of the capital in the year of Jiashen (1644) and the suicide of Emperor Chongzhen brought indelible pain, described by the painter and calligrapher Wan Shouqi (1603-1652) and the poet Fang Yizhi (1611-1671) as "a time when the sky was full of blood" when "the earth cracked, the sky collapsed, and the sun and moon dimmed." This feeling of grief was directly expressed in a portrait by Xiang Shengmo and Zhang Qi (dates of birth and death unknown). Xiang Shengmo was originally named Yi, later Kong Zhang, and was also known as Yi'an. He was the grandson of the great collector Xiang Yuanbian. He benefited from his family's collection of famous paintings from past dynasties since he was a child, and was also influenced by Dong Qichang's teachings of "learning from the ancients". His painting style was calm and law-abiding. But the fall of the Ming dynasty stimulated him to create a number of emotional portraits. This unusual "Self-portrait in Vermilion Landscape" places his black-and-white portrait (painted by Zhang Qi) between his own vermilion landscape. The poem on the painting directly explains the symbolic meaning of the color contrast: "The remaining water and the remaining mountains are still red, the sky is dark and the earth is dark, and the shadow is tiny. The red heart is burning and I paint the cinnabar, and my thirsty brush is ashamed to paint." The reason for creating this painting is recorded after the poem: "In the fourth month of the Jiashen year of Chongzhen, I heard about the incident in the capital on March 19th, and I became ill with grief and anger. After waking up, I painted his face in ink and supplemented it with red painting. My feelings are expressed in poems to record the years. Xiang Shengmo, a minister in Jiangnan, was forty-eight years old at the time."

Portraits of characters in "Self-written Portraits of Vermilion Landscapes"

As the poem says, the vermilion landscape symbolizes the now shattered Ming Dynasty, while the black portrait represents Xiang Shengmo's "tiny" figure in the national crisis. This work thus shows the artist's immediate reaction to the Jiashen Rebellion, and also marks the beginning of his period of survival. The fall of the country led to the fall of the family: the following year, when the city of Jiaxing was massacred, Xiang Shengmo fled with his mother and wife; his cousin, Xiang Jiamo, the garrison commander of Ji Liao, refused to surrender to the Qing Dynasty and committed suicide by jumping into Tianxin Lake with his two sons and a concubine. Xiang Shengmo recalled in the postscript of "Three Moves to Hidden Picture": "... In the summer of the next year, from the south of the Yangtze River, soldiers and civilians were scattered, and the war horses were running. On the 26th day of the sixth month of the leap year, Hecheng (Jiaxing) fell and the fire was burning. I was the only one who fled far away with my mother and wife, and my family was broken. All the calligraphy and paintings left by my ancestors that my brothers and I had collected, and those that were scattered in the world in the past, were half turned into ashes and half trampled." From then on, he did not write the dynasty title on the painting, but only used the sexagenary cycle to record the years, and stamped the seals such as "Minister in the Wilderness of Jiangnan", "Jiahe Hermit from the Imperial Ming Dynasty", and "Liaoxi County People since the Great Song Dynasty Migrated to the South" to express his intentions. "The Wind Screaming at the Big Tree" created by him in 1648 depicts a scholar in a red shirt and a cane standing under a huge dead tree dotted with vermilion, implying memories and mourning for the past dynasties.

Xiang Shengmo, "Big Tree Howling in the Wind", Qing Dynasty, Collection of the Palace Museum

These two paintings show an important artistic direction of a group of "loyal" painters after the fall of the Ming Dynasty. For these people, even if they still survived, their real lives had been interrupted at the moment of the collapse of their country. Fang Yizhi therefore questioned himself in a "Self-Sacrifice": "Are you going to die today? I died in Jiashen!" This imaginary martyrdom is often expressed through symbolic gestures and behaviors, such as Gui Zhuang (1613-1673) and Chao Mingsheng (1611-1680) imprisoning themselves in a cemetery like living dead; others expressed their mourning for the previous dynasty through aphasia and feigned madness. In order to preserve the memory of their homeland and resist the fact of the change of dynasties, these literati painters used various methods to maintain their inner spiritual world in images and poems. One method was to establish a supra-historical connection with the previous generations of loyalists. A typical work is the "Reminiscence of the Past" created by the loyalist painter Yang Bu (1598-1657) in 1648, which consists of ten pages of pictures and texts.

Lying in the Snow, from Yang Bu's Album of Ancient Poems and Pictures. Qing Dynasty, from the collection of Shanghai Museum

Earthen House, from Yang Bu's Album of Ancient Paintings and Poems. Qing Dynasty, from the collection of Shanghai Museum

Yang Bu was from Linjiang (now Qingjiang) in Jiangxi Province. His courtesy name was Wubu and his pseudonym was Gunong. After the fall of the Ming Dynasty, he fled to Dengyu Mountain in Jiangsu Province and lived in seclusion there, where he died in depression. He depicted ten historical figures in this album, one of which, Lying in the Snow, depicts Jiao Xian, a hermit in the late Han Dynasty, who abandoned his clothes and hats, ate grass and drank water, and made a hut out of grass in the troubled times. In the painting, Jiao Xian lies on a desolate snowy bank, taking the world as his home, and the cold of the severe winter adds to the gloomy atmosphere of the picture. Another person depicted in the Earthen Room in the album is Yuan Hong of the Later Han Dynasty, who lived in seclusion with his hair untied during the party struggles in the late Han Dynasty, confined himself in an earthen room without a door, and only received food through the window. These images can be considered as the painter's self-projection, which not only shows their moral values, but also pays tribute to their spiritual predecessors.

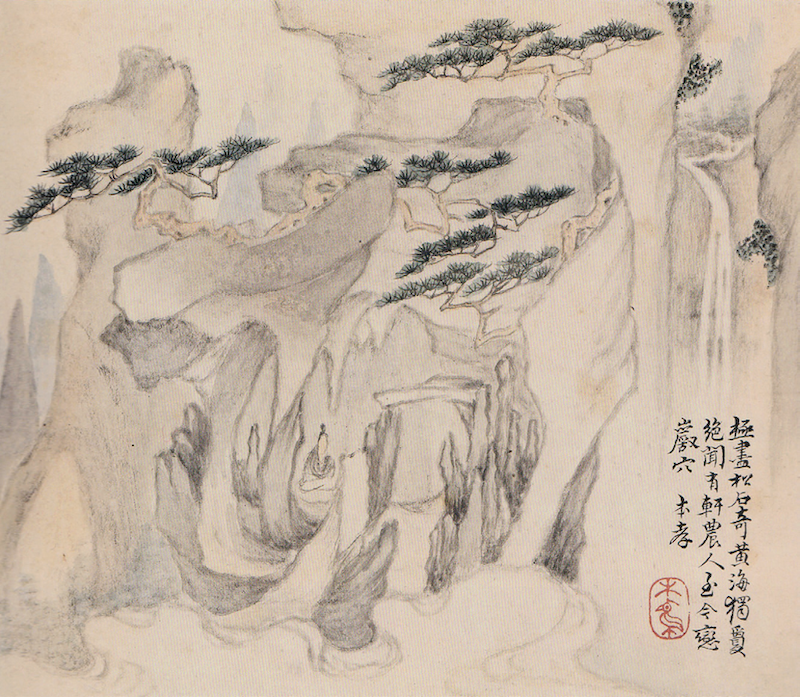

Dai Benxiao, "Maonv Cave in Huashan". Qing Dynasty, Zhejiang Provincial Museum

The landscape paintings of the remnants of the Qing dynasty often contain a solitary figure, either walking alone in the mountains or alone in a cave or thatched cottage. These images are often of vague time and can be read as either historical figures or the reclusive painter himself. The "man in the cave" repeatedly depicted by the remnant painter Dai Benxiao belongs to this category. Dai Benxiao was from Hezhou (now Hexian) in Anhui Province. His courtesy name was Wuzhan and his pseudonym was Qianxiuzi. His father, Dai Chong (1601-1646), was an anti-Qing fighter who died of starvation after being wounded. Dai Benxiao followed his father's wishes and refused to serve as an official in the Qing court. He lived in seclusion in Ying'a Mountain as a commoner. He painted many "man in the cave" images, some of which depicted the legendary Maonu, who fled the tyranny of Qin Shihuang and took refuge in the caves of Huashan Mountain, while others depicted ancient sages and hermits such as Gao Yao, Chaofu, and Xu You, or the painter himself.

Dai Benxiao, "The Man in the Cave". Qing Dynasty, Shanghai Museum

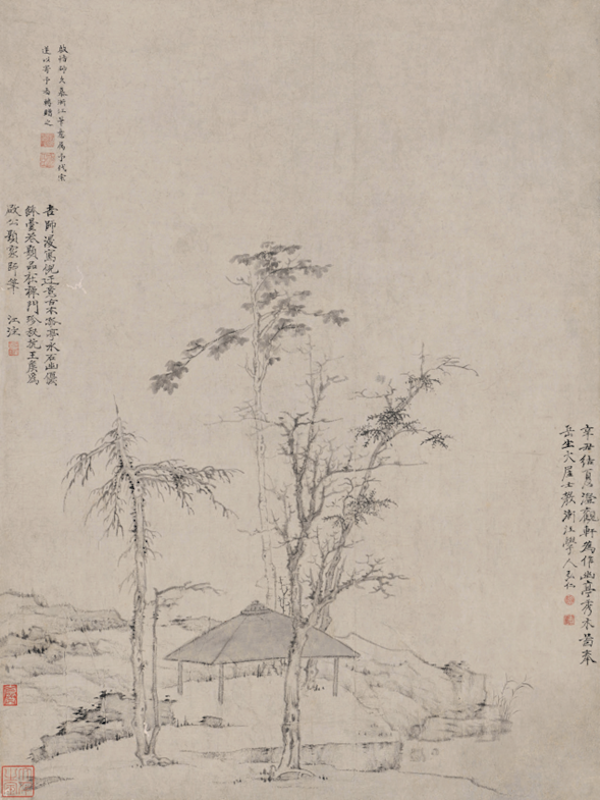

Other common symbolic images in the paintings of the Ming loyalists include empty pavilions, inscriptionless monuments, and the tomb of Emperor Taizu of the Ming Dynasty. These images all remove the focus of the painting, thus witnessing a common visual strategy of the paintings of the Ming loyalists. The theme of the empty pavilion originated in the Yuan Dynasty with Ni Zan, and became ubiquitous in the paintings of the Ming loyalists at this time, sometimes even magnified into an iconic central image, as shown in Hongren's "Picture of Secluded Pavilion and Beautiful Trees".

Hongren, "A Quiet Pavilion and Beautiful Trees". Qing Dynasty, Collection of the Palace Museum

Dai Benxiao and Zhu Da painted empty pavilions on steep cliffs, further reinforcing the sense of self-isolation.

A painting from Dai Benxiao's Landscape Painting. Qing Dynasty, collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Zhu Da, Landscape Painting. Qing Dynasty, Freer Gallery of Art

The wordless stele is another emptied image in the paintings of the survivors. The stele is the most important object in Chinese culture to commemorate the dead or historical events, and is usually engraved with long inscriptions. However, the stele paintings by Zhang Feng (?-1662) and Wu Li only have blank surfaces. The former depicts a scholar in Ming Dynasty clothing on a fan, standing in front of a huge stele in a desolate field.

Zhang Feng's "Reading the Inscription" fan leaf. Qing Dynasty, Suzhou Museum

(Attributed to) Li Cheng, "Reading the Stone Tablet". Copy from the Song and Yuan Dynasties, Osaka City Museum of Art

This composition clearly echoes the "Reading the Stone Tablet" attributed to Li Cheng of the Northern Song Dynasty, but it has been given a new meaning in the context of the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Zhang Feng's courtesy name is Dafeng, and his pseudonyms are Shengzhou Taoist and Shangyuan Old Man. He was a student in the late Ming Dynasty. After the fall of the Ming Dynasty, he did not serve as an official. He lived in Nanjing as a survivor and went north to pay homage to the Ming Tombs. This fan painting, painted in 1659, is likely related to this trip. The inscription on it reveals a strong sense of nostalgia: "Cold smoke and withered grass, ancient trees in the distance, monuments standing out, no traces of people around, looking at this makes people feel the past and the present."

Wu Li, "White Clouds and Green Mountains". Qing Dynasty, Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Part of "White Clouds and Green Mountains"

The inscriptionless stele is also the focus of Wu Li's "Clouds, White Mountains and Green Mountains". Wu Li was only 13 years old when the Ming Dynasty fell, but he remembered his ancestors' reputation in the Ming Dynasty and studied under famous scholars of the Ming Dynasty. He eventually became a loyal "second-generation survivor" and lived his life as a commoner. He converted to Catholicism in middle age and went to Macau to work for the church at the age of 50. This painting was created in 1668 when he was 37 years old. It conveys the sadness of the country's fall in a very subtle way. The composition and green style of the painting are intentionally echoed by the popular "Peach Blossom Spring". "Peach Blossom Spring" written by Tao Qian in the Jin Dynasty tells the story of a fisherman who accidentally passed through a cave and discovered an isolated utopian paradise where the ancestors of the residents fled here during the turmoil of the Qin Dynasty. From then on, they lived a quiet and unchanging life without knowing the world. Wu Li imitated the commonly seen "Peach Blossom Spring" and painted a flowering peach tree half-covering a cave in the front of the scroll, but the image at the back of the scroll shocked the viewer who continued to unfold the scroll: there was no peaceful paradise and happy residents here, but instead there was a stone tablet without words, standing silently under the dead tree, and a group of crows circled in the sky, blocking the sunlight. Echoing this bleak scene, Wu Li began his poem at the end of the scroll with the sentence "The rain has stopped and the sea smells fishy" - the Qing Dynasty's conquests are a thing of the past, and any hope of restoring the previous dynasty has been shattered.

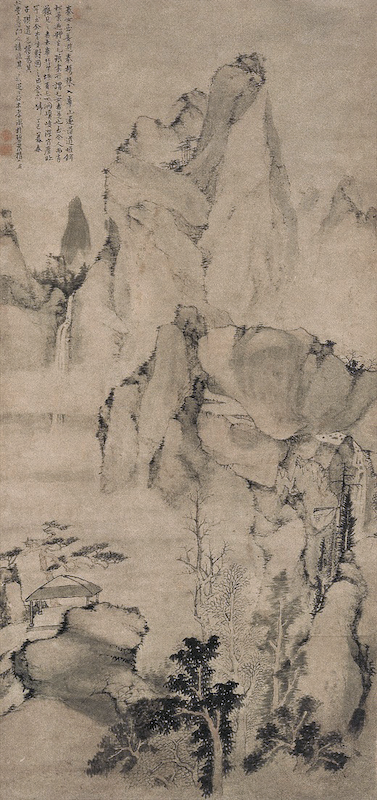

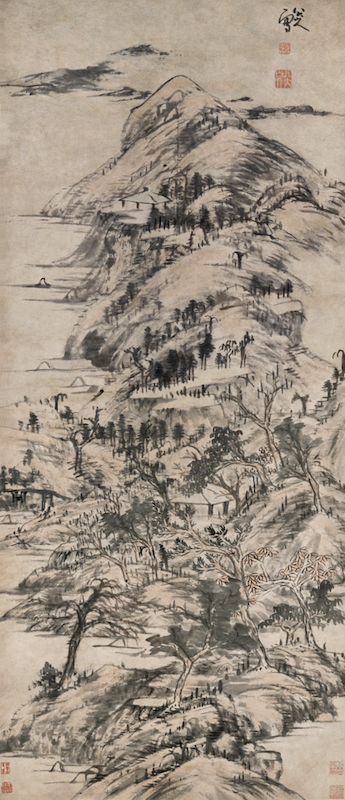

Gong Xian, Landscape. Qing Dynasty, Honolulu Museum of Art

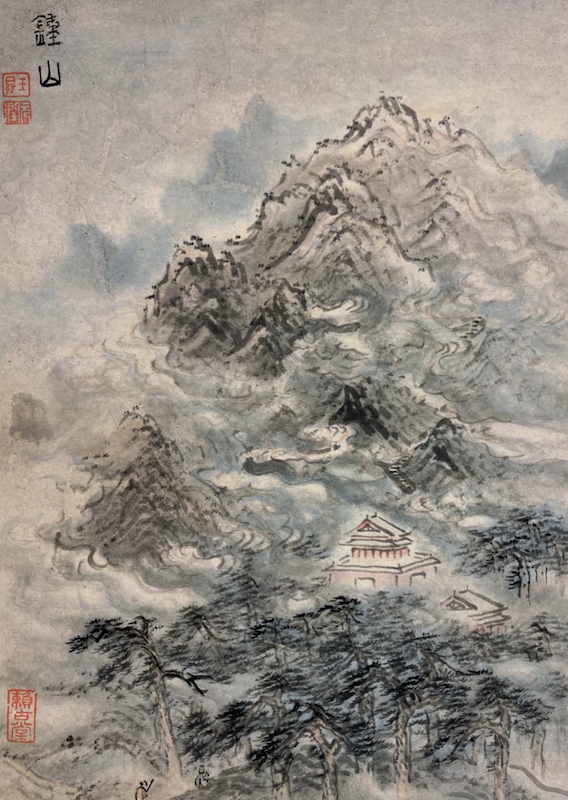

After the fall of the Ming Dynasty, the Xiaoling Mausoleum of Emperor Taizu Zhu Yuanzhang in Nanjing Zhongshan became a place of worship for the survivors. In their minds, this desolate imperial mausoleum hinted at the change of dynasties and their own unfortunate fate. Among the Jinling painters, Gong Xian, Gao Cen (1621-1691), Hu Yukun (1607-after 1687) and the younger Shi Tao all painted this holy place of the former dynasty. They placed the Ming building in front of the tomb in the center of the picture, and used the towering peaks to highlight the monumentality of the building. Gong Xian's "Landscape" hanging scroll, now in the collection of the Honolulu Museum of Art, was particularly inspired by the "grand mountains and halls" composition of the Northern Song Dynasty, inlaying the Ming building of the Xiaoling Mausoleum between the cold forest in the foreground and the high peaks in the distance. Hu Yukun's Album of Scenic Spots in Nanjing depicts the same building with the words "Zhongshan" inscribed in seal script in the upper left corner. However, what the viewer sees is not a majestic mountain, but mountains, rivers and trees depicted with violently undulating lines, as if the entire universe is in turmoil.

A painting from Hu Yukun's Album of Jinling Scenic Spots. Qing Dynasty, collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

These works show that the paintings of the remnants not only introduced special symbolic images to express the painters' feelings about their life experiences and thoughts about their homeland, but also tried to maximize the role of painting in expressing their temperament through innovation in style. Therefore, the core of the paintings of the remnants is the preservation and development of the painters' individuality. Therefore, we can understand why the successful remnant painters all opposed following the old ways and emphasized expressing their own personalities.