Since modern times, a large number of ancient Chinese paintings and calligraphy have been pouring into Japan, which is called "new arrival" or "new shipload". They interact with Japan's existing "old arrival" collections, causing waves in the fields of collection, exhibition, publication and research. Recently, the book "Research on the Spread of Ancient Chinese Paintings and Calligraphy in Japan (1880-1945)" (written by Su Hao and Qiu Ji) published by Zhejiang Gongshang University Press has deeply studied this complex historical process and also explored the cultural identity anxiety reflected in Japan's collection of ancient Chinese paintings and calligraphy.

The historical process of the introduction of modern Chinese calligraphy and painting into Japan presents a complex social background and historical trajectory. After the Revolution of 1911, the political situation was turbulent, and Chinese calligraphy and painting flowed into Japan on an unprecedented scale. At that time, Japan's economy was booming. Under the joint promotion of Chinese and Japanese collectors, the emerging wealthy groups actively devoted themselves to the collection of Chinese calligraphy and painting, and gradually formed two major collection centers in Kanto and Kansai. The Chinese calligraphy and painting that flowed into Japan at this time were called "new crossing" or "new shipload", which complemented Japan's original "ancient crossing" and filled the gap in Japan's collection system. The flow of cultural relics and academic research promoted each other. The influx of a large number of collections stimulated extensive discussions and research in the Japanese academic community. Relevant monographs have been published one after another, and many of the classic works have been translated and introduced back to China, which in turn had a profound impact on the writing of Chinese art history.

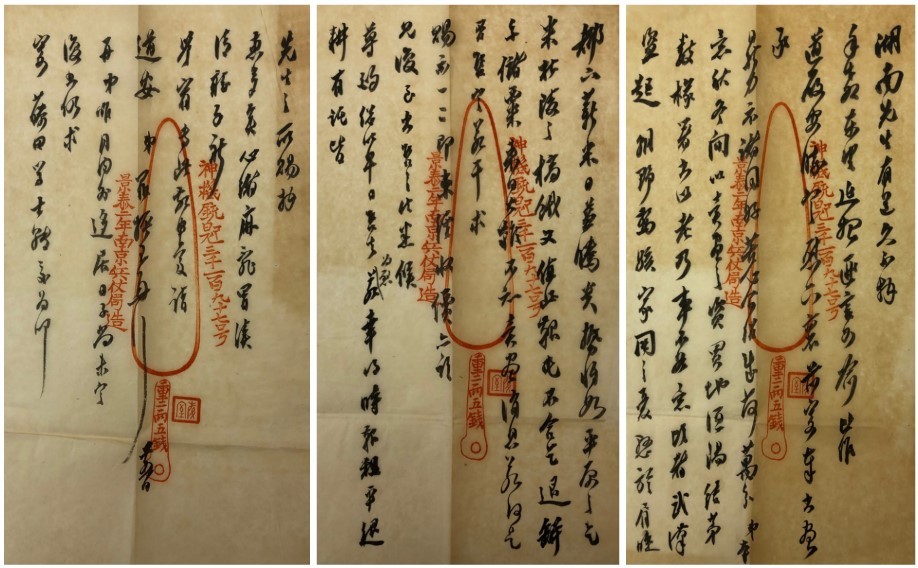

Japanese academic circles have already made rich research achievements on the spread of modern Chinese calligraphy and painting in Japan, but Chinese scholars have rarely been involved due to the difficulty in obtaining materials or language restrictions. However, whether it is the screening of materials or the research stance and historical narrative, the participation of local Chinese scholars is needed. The history of the loss of Chinese cultural relics should be written in the research paradigm of Chinese scholars. Only in this way can the integrity of the academic perspective be ensured. The book "A Study on the Spread of Ancient Chinese Calligraphy and Painting in Japan (1880-1945)" written by Su Hao and Qiu Ji takes the opening of Sino-Japanese air routes around 1880 as the starting point and ends with the defeat of Japan in 1945. It systematically examines the circulation, collection, exhibition, publication and research of "newly crossed" Chinese calligraphy and painting in Japan during this period, and deeply analyzes the impact it has produced. The book focuses on key figures and institutions, and discloses a large number of precious historical materials currently stored in Japan, including letters, exhibition catalogs, magazine articles, etc. from collectors in China and Japan. Through in-depth interpretation of first-hand materials, it shows the spread of modern Chinese calligraphy and painting in Japan, and deeply analyzes the cultural and social factors behind this phenomenon.

This book is divided into two parts. The first part, "The Transmission of Ancient Chinese Paintings and Calligraphy to the East and the Sino-Japanese Collector Network", is based on the perspective of collectors and is divided into four chapters. It selects four representative Chinese and Japanese collectors, Duan Fang, Luo Zhenyu, Nakamura Fusetsu, and Yamamoto Jingshan, for case studies, aiming to sort out the process of the "New Transmission" of Paintings and Calligraphy to the East and the formation of the Japanese collection circle. Among the two selected Chinese collectors, Duan Fang is particularly noteworthy. He was both a high-ranking official in the late Qing Dynasty and a collector of paintings and calligraphy. He generously displayed his private collections and used this as an opportunity to engage in "painting and calligraphy diplomacy" with Japanese politicians (such as Inukai Tsuyoshi) and academics (such as Naito Konan and Taki Seiichi). This action inadvertently provided a "collection guide" for the Japanese painting and calligraphy market. Although Duan Fang opposed the loss of cultural relics overseas, after his death, his collections still became the object of pursuit in the Japanese painting and calligraphy market and were sold to Japan. Luo Zhenyu was more active in promoting the exchange of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy and painting. He not only sent his own collection to Japan for exhibition and sale, but also, together with Wang Guowei, actively mediated the transaction of collections between Chinese and Japanese collectors as an intermediary, playing a pivotal role in the surge in the number of Chinese calligraphy and painting collected by Japan in modern times and the formation of the market. The eastward transmission of the old collections of Duan Fang and Luo Zhenyu not only set off a wave of Chinese calligraphy and painting collections in Japan, but also greatly promoted the development of related research. In the part of Japanese collectors, this book selects two representative collectors from Kanto and Kansai regions of Japan: Nakamura Fusetsu and Yamamoto Jingshan. They both went to China to collect calligraphy and painting tablets and actively established calligraphy research groups, conducted in-depth research and comments on the collections, and showed their multiple identities as artists, scholars and collectors. In terms of the source of the collections, the two are different: Nakamura Fusetsu's collection mainly benefited from the assistance of Japanese antique intermediaries such as Tanaka Wenqiutang; while Yamamoto Jingshan's collection was more based on the extensive collection network built with antique dealers and Chinese and Japanese literati. In this network, Yamamoto Jingshan was not only an active buyer of old collections of Chinese literati (such as Yang Shoujing and Luo Zhenyu), but also served as a purchasing agent and appraisal consultant for Japanese chaebols (such as Mitsui Takashi).

Figure 1 Letter from Luo Zhenyu to Naito Konan, collected by Kansai University

Figure 2 Yan Zhenqing's "Self-written Letter of Appointment" (partial) purchased by Nakamura Fusetsu in 1930, collected by Taitung District Calligraphy Museum

Figure 3 Some of the Chinese literati business cards collected by Yamamoto Jingshan, collected by Kansai University

The second part, "Traditional Exhibitions and Knowledge Production of Ancient Chinese Paintings and Calligraphy", has a broader vision, examining the spread of Chinese paintings and calligraphy in Japan in the context of a broader political and social history. Chapters 5 and 6 focus on the theme of "exhibitions", and deeply analyze the holding of a series of important exhibitions such as the 1913 Taisho Tokyo-Kyoto Lanting Exhibition, the 1913 Kyoto and Chinese Calligraphy Exhibition, and the 1922 Chibi Exhibition, pointing out that these exhibitions not only displayed a large number of precious Chinese calligraphy tablets and posts, promoted the exchange of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy, but also promoted the development of Japanese calligraphy. Chapters 7 and 8 turn to the field of "publishing". Chapter 7 sorts out the Chinese paintings and calligraphy works that were photocopied and published by Bowentang using collotype technology, and deeply explores how this modern new technology has improved the accuracy and circulation efficiency of painting and calligraphy reproduction, thereby changing the mode of painting and calligraphy dissemination. Chapter 8 analyzes the Chinese calligraphy tablets and posts and calligraphy articles published in Japanese calligraphy magazines such as "Shuyuan" and "Shuwan", revealing the important role played by academic journals in the process of knowledge production and the shaping of artistic concepts. Chapter 9 focuses on the "research" level, systematically combing the paradigm construction of Chinese calligraphy and painting research in the 20th century Japanese art history circle, and analyzing its academic value, influence and limitations. For example, Omura Nishigaya, Xiaolu Qingyun, Nakamura Fusetsu, Higuchi Tongniu and others wrote a general history of Chinese painting and calligraphy, laying the foundation of the discipline; Taki Seiichi, Naito Konan and others shifted the research perspective from historical factual research to theoretical discussion, promoting the in-depth research; Aoki Masao, Kanehara Shogo and others conducted in-depth case studies on Chinese calligraphy and painting. These pioneering research works have also had a direct inspiration and far-reaching impact on Chinese scholars' calligraphy and painting research after being translated and introduced in modern times.

Figure 4 Kyoto Lanting Society commemorative postcard (partial) Kyoto National Museum collection

Figure 5 Book photos from Shuyuan and Shuwan magazines

Figure 6: Book cover of Nagao Yushan’s “Talks on Chinese Painting and Calligraphy”

The appendixes of this book are also rich in content. Appendix 1, "Compilation of Ancient Chinese Paintings and Calligraphy Flowing into Japan in Modern Times", systematically organizes the information of nearly 3,000 "newly transferred" collections in eastern and western Japan. It not only briefly introduces the identities, collecting interests and collecting activities of the collectors in the two places, but also lists all the collections and their current collection locations in detail; Appendix 2, "List of Some Collections Flowing into the Art Market/Museum", selects some important collections, lists their original Japanese collectors, era, author, name, material, size and other information, and briefly explains their auction situation and current collection location; Appendix 3, "Research on the History of Chinese Painting in Japan in the 21st Century - Focusing on Landscape Painting", sorts out the four directions of landscape painting research in the Japanese academic community in the past 20 years, providing a reference for the Chinese academic community from the perspective of "others". The three appendices collect detailed information and clearly arrange the paintings and calligraphy flowing into Japan, which not only constitutes a systematic compilation, but also provides a review of related research, which is both instrumental and documentary, and lays a solid foundation for subsequent research.

Figure 7 Muqi's "Returning Sails from a Distant Harbor" (one of the Eight Views of Xiaoxiang) Kyoto National Museum

The highlights of "A Study on the Spread of Ancient Chinese Paintings and Calligraphy in Japan (1880-1945)" co-authored by Su Hao and Qiu Ji are reflected in the following three aspects. First, the book discloses and interprets a large number of original Japanese materials, especially the letters of Chinese and Japanese literati collected by Kansai University, which greatly supplements the narrative gap in the relevant field in the domestic academic community and provides new perspectives and evidence for research. Secondly, based on solid historical research and meticulous case analysis, the author systematically sorts out the complex process of the spread of ancient Chinese paintings and calligraphy to Japan. The research not only focuses on key figures and institutions, but also expands the field of publishing history and social history, constructing a trinity of publishing, exhibition, and research after the works flowed into Japan, reflecting the innovation of interdisciplinary research. Finally, the book goes a step further, using art as a prism to reflect the changes in cultural power in modern East Asia, and deeply explores the cultural identity anxiety reflected in Japan's collection of Chinese paintings and calligraphy. In short, the book not only provides readers with rich historical materials and in-depth analysis, but also helps to further understand the history and current situation of the flow of modern Chinese paintings and calligraphy into Japan.

Note: The author of this article is from the Palace Museum. The original title of this article is "The Circulation and Collection of Chinese Paintings and Calligraphy in Modern Times - Comments on "A Study on the Spread of Ancient Chinese Paintings and Calligraphy in Japan (1880-1945)"