A geranium reflects the shadow of civilization in the philosopher's mirror and blooms a carnival of colors under the painter's pen.

As expected, Matisse, who was fascinated by colors, also liked flowers. He said, "Those who want to see flowers will always see flowers." Geranium is probably the most photographed flower in his still life paintings.

In early summer, when the grass and trees are lush, I always think of Matisse. He likes to use rich and pure colors to paint lazy women and small scenes of life, with simple and naive lines, and is smart and unrestrained. I have seen Matisse's special exhibitions in Berlin and Boston. As a philosophical dabbler wandering on the edge, although I occasionally see the undercurrents under the surface of the harmonious and bright middle-class life from the paintings out of my professional instinct, most of the time, my appreciation of art is irrelevant, and I just like to pick some wild cotton, such as the flowers in Matisse's paintings.

Matisse, who was fascinated by colors, unsurprisingly liked flowers. He said, "Those who want to see flowers will always see flowers in their eyes." So I can always see flowers in his paintings. The flower that appears most frequently in his still life paintings is probably geranium. Especially in the first decade of the 20th century, small potted red geraniums often appeared in his paintings.

The Chinese translation of geranium naturally reminds people of India, but according to the research of Anne Wilkinson, a gardening historian, in "Infatuation with Geranium", this plant is actually native to South Africa and was brought back to Europe by Dutch plant hunters from the Cape of Good Hope in the 17th century. Since the Cape of Good Hope was a must-go place for Europeans to go to India at that time, this plant that emits the fragrance of bergamot at night was first brought to India and then returned to Europe. In addition, it is somewhat similar to the native European geranium, so it was named night-scented Indian Geranium, and was also classified into the genus Geranium by Carl Linnaeus, the ancestor of plant classification.

It was not until the 18th century that a French botanist with a name so long that one can't bear to pronounce it (Charles-Louis L'Heritier de Brutelle) officially distinguished this exotic plant that was neither frost-resistant nor heat-resistant from the tough perennial geranium and made it an independent genus (Palargonium). With the British colonization of the Cape of Good Hope, more and more geranium varieties were introduced to Britain. Geraniums spoiled by the warm climate of South Africa were carefully domesticated by British gardeners in greenhouses. Artificially cultivated hybrids were popular as interior decorations in the Victorian era, and then crossed the English Channel and became popular in Europe, especially in France, and have remained popular to this day.

Although the potted plants in Matisse's paintings are still called geraniums in the title of the painting, I am willing to believe that they are actually geraniums from South Africa, given his careful care in maintaining them in indoor flower pots and his preference for exotic styles. However, it is interesting that the exquisite taste in the eyes of painters may not be so lovely in the eyes of philosophers.

Rousseau was probably the most enthusiastic botanist among philosophers, except for Aristotle. He had a bad temper and was always clumsy and aggressive in social life. He couldn't even get along with the elegant and gentle Hume. But when he was with plants, he was infinitely gentle, humble and patient. In "Reveries of a Solitary Walker", he mentioned that the plants on Saint-Pierre Island saved him from the hustle and bustle of Parisian life and restored his crazy mind to peace. In his correspondence, he would use a whole letter to describe the amazing details about a flower tirelessly. He regarded botany as a reward for pure curiosity. In addition to bringing simple happiness to sensitive people through observing the wonders of nature and the universe, it had no practical use. When geraniums were introduced to Europe during the colonial era, exotic flowers and plants were captured, classified, domesticated, and developed as prey, and could be used as medicine, or made into incense, or as exquisite decorations for wealthy people. But in Rousseau's eyes, this pursuit of practicality was a kind of degeneration. I guess if Rousseau saw the geraniums separated from their native habitat and kept in a greenhouse, it would be like seeing himself who was out of place in the Parisian social circle.

Fortunately, our painter Matisse is not as reflective as Rousseau. Philosophers always have a morbid obsession with metaphysics and skepticism. Although life without reflection is not worth living, it does not prevent it from being worth painting. This talented painter, who picked up the brush at the age of 20 because of boredom during his illness, used fresh colors that rushed to the face and hit the eyeballs, and arbitrarily created a vivid visual world, in which the geraniums are warm and warm.

In the exhibition, Matisse's "Geranium" 1912

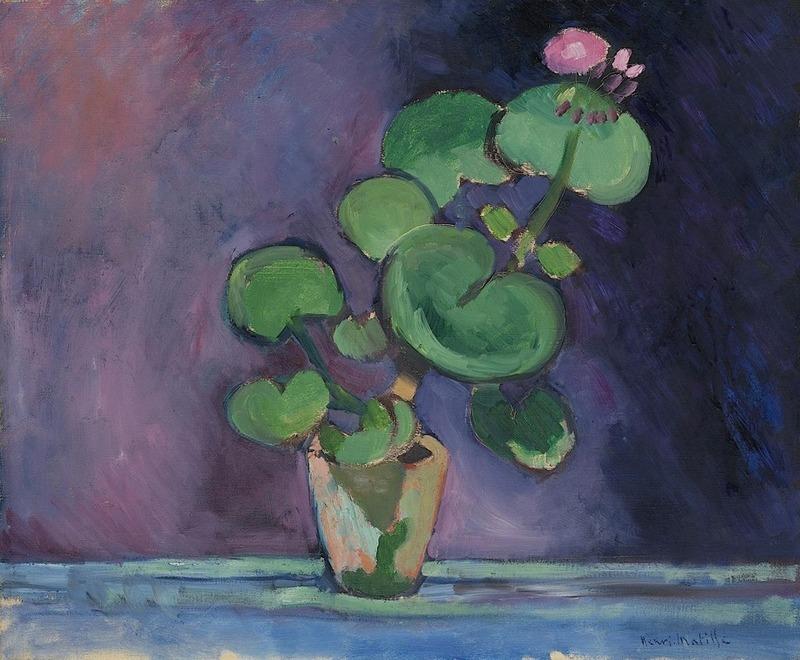

Among them, the most distinctive one is the "Pot Geranium" created in 1912 that I saw in the National Gallery of Art in Washington. This is an upright variety of geranium, which looks like a new seedling from cuttings that year. The branches are still fleshy green, and fresh moss grows on the red pottery pot - moss can only grow in an environment with fresh air, moisture and ventilation, so I guess it should be placed on an open-air flower stand in the courtyard. Except in hot summer weather, geraniums like to bask in the sun without any obstruction. The strong contrasting shadows under the leaves and behind the pots show that this place has good sunlight, so the plant grows short and strong, and blooms early, which is quite similar to the potted seedling I took from cuttings, and even the flowers blooming on the umbel are exactly two!

A pot of seedlings planted by the author

This one, painted in 1910 and seen at the Harvard University Art Museum, is in full bloom. The potted plant is placed on a porcelain plate with blue and purple petals painted on it. The wallpaper in the background is full of colorful morning glories, and a purple flower that appeared out of nowhere has mischievously fallen on the ochre table. These colors and flowers are so lively and inexplicably put together, yet calmly. This geranium in the center of the photo, in terms of flower color, is very similar to the orange angel geranium I have raised, but the leaves and flowers of the angel are very small, while the size of Matisse's geranium is more like the Regal (also translated as large flower type in China) geranium cultivated by French gardeners.

Matisse, Geranium, 1915

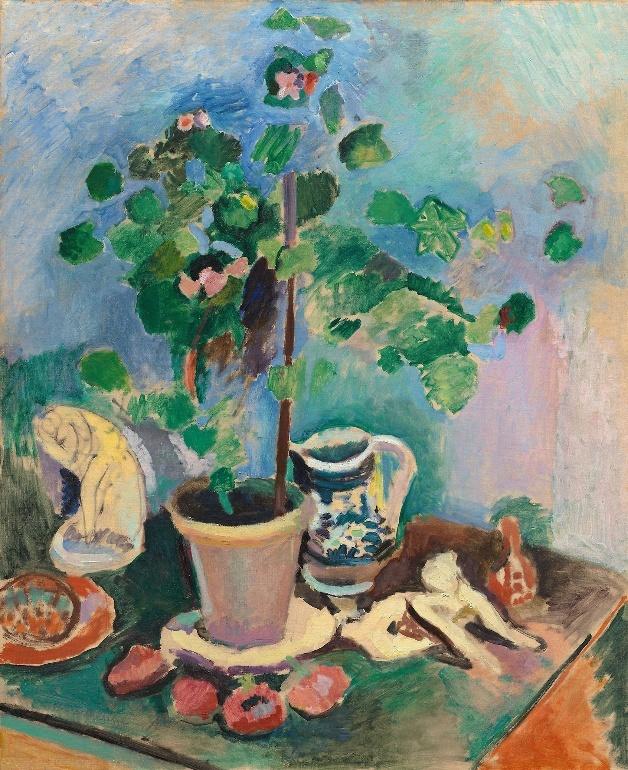

In comparison, the one from 1906 is not doing so well. I always feel pity for this light-loving plant that lives in the corner of the room. Although it blooms, it is obviously thin and green, probably because it is placed indoors without enough light. The branches and leaves are too long, and it seems that a wooden stick is needed to support the thin branches. Even though the color is rich, it is a sad geranium.

Matisse, Geraniums and Still Life, 1906

This one from 1910 is growing with its neck tilted towards the sun. In fact, if you rotate the flowerpot from time to time to evenly expose the branches and leaves to the sun, the plant will become round and plump. The more I look at it, the more I want to rush in and help him rotate the flowerpot and top and pinch the stems to promote branching.

Matisse, Geraniums, 1910

But even so, these geraniums in Matisse's house are much better than the one in Cézanne's house, his idol. They are lush, tall and strong, but they just don't bloom! Cézanne must have been very upset when he painted these two geraniums. Fortunately, he had enough flowers in his garden in Gédebouffon. He even tried his best to fight against the overly strong sunlight in the south. He only preferred the soft light that came through the clouds or leaves in the morning and danced in the garden. Such light is a luxurious nurturing for flowers, so he also prefers to paint flowers in nature rather than indoor bouquets. Of course, another important reason is that he painted too slowly, and the flowers he picked withered before he finished painting. Although these two geraniums that didn't bloom were disappointing, they gained unexpected calmness.

Paul Cezanne, Geraniums, 1888-1890

In fact, neither Matisse nor Cézanne intended to be realistic. It is inevitable that the careful distinction of species and habitats in their paintings is a bit nerdy and futile. If you want to know the details of plants, you should look at botanical scientific paintings instead of fighting with Fauvism. However, as a "wild" gardening enthusiast, I am always attracted by the beauty and scent of flowers, just like when we are attracted by a beauty, we always forget to ask about her background and family background. I have never been very knowledgeable about the hard stuff of botany, such as genus and subject.

Botanical scientific paintings always give me the feeling of looking at human anatomy diagrams. Even a woman who is extremely beautiful cannot withstand the scalpel's unraveling. Hume wrote at the end of "A Treatise of Human Nature": "The anatomist should never compete with the painter: although the anatomist has made accurate dissection and description of the subtle parts of the human body, he should not pretend to give his characters any elegant and moving attitudes or expressions." Hume used anatomy to compare abstract speculation on human nature, while the scenery and human feelings described by the painter were compared to ordinary life. His original intention was certainly not to belittle philosophy. Philosophy can explore human nature, analyze language and concepts, but it is ultimately a bit cold and boring. Life still requires soothing persuasion and persuasion. Similarly, Matisse's simple brushstrokes and vivid colors always open my perception better than the detailed botanical paintings. I seem to walk into that day in the studio in Paris, smelling the warmth of the sun, the flow of air, and the emotions of geraniums.

(The author is a professor in the Department of Philosophy at East China Normal University)