The upcoming Chinese Valentine's Day is the most romantic of my country's traditional festivals. It originated from the ancient people's worship of the universe and celestial phenomena, and later incorporated into the love legend of the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl, and gradually evolved into a comprehensive festival with the themes of praying for blessings, begging for ingenuity, and love.

When we gaze at ancient paintings from the Wei, Jin, Southern and Northern Dynasties to the Qing Dynasty, the women leading strings under the moon and the fairies gazing at each other across the Milky Way, we seem to hear whispers that have spanned thousands of years - the desire for wisdom and ingenuity, the persistence in love, and the prayers for beauty have always been the unfading background of Chinese civilization.

Love of Star Gods: From Celestial Worship to the Artistic Sublimation of Love Legends

The origins of Qixi Festival can be traced back to ancient star worship. The Book of Songs, Xiaoya, Dadong, already contains anthropomorphic descriptions of Altair and Vega: "On tiptoe, the Weaver Girl weaves, all day long... Glancing at the Cowherd, he does not use them to make a box." At this time, the stars were not yet associated with love, but rather observed as astronomical symbols. During the Eastern Han Dynasty, the story of the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl began to be personified. Ying Shao's "Comprehensive Meaning of Customs and Customs" states: "On the Qixi Festival, the Weaver Girl crosses the river, using magpies as a bridge." The legend of the meeting on the magpie bridge has since become a core theme in artistic creation.

The Eastern Han Dynasty stone relief "Cowherd and Weaver Girl" (unearthed in Nanyang, Henan) vividly depicts this myth through the integration of constellations and figures: the Cowherd leads the Cowherd, gazing upwards, while the Weaver Girl sits at her loom. Their gaze, symbolized by the Milky Way, is separated by a cloud pattern, embodying the sentiment of "across the water, yet unable to speak a word of affection." This compositional pattern set the tone for later painting—a dual narrative of the celestial galaxy and the human pursuit of wisdom.

During the Wei, Jin, and Southern and Northern Dynasties, Qixi Festival customs became more diverse, with begging for skill becoming its core custom. Not only did they inherit the Han Dynasty traditions of threading seven-hole needles and hanging clothes outdoors, but they also offered melons and fruits as sacrifices to the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl. The Southern Dynasty's "Jingchu Sui Shi Ji" by Zong Yan records the seventh day of the seventh month: " On this evening, women build colorful towers, thread seven-hole needles, or use needles made of gold, silver, or stone. They display melons and fruits in the courtyard to beg for skill. If a net with a lucky charm is placed on a melon, a talisman is used as a response. "

The Xizi (a small, red, long-legged spider) is believed to have won the favor of the Weaver Girl (Zhi Nu), promising her a clever mind and good luck. Gu Yewang of the Southern Dynasties, in his "Geographical Records," also recorded that during the reign of Emperor Wu of the Southern Qi Dynasty, Xiao Zhao, a tower was built. Every July 7th, palace maids would ascend this tower to thread their needles. This tower became known as the "Threading Needle Tower," reflecting the widespread popularity of the custom.

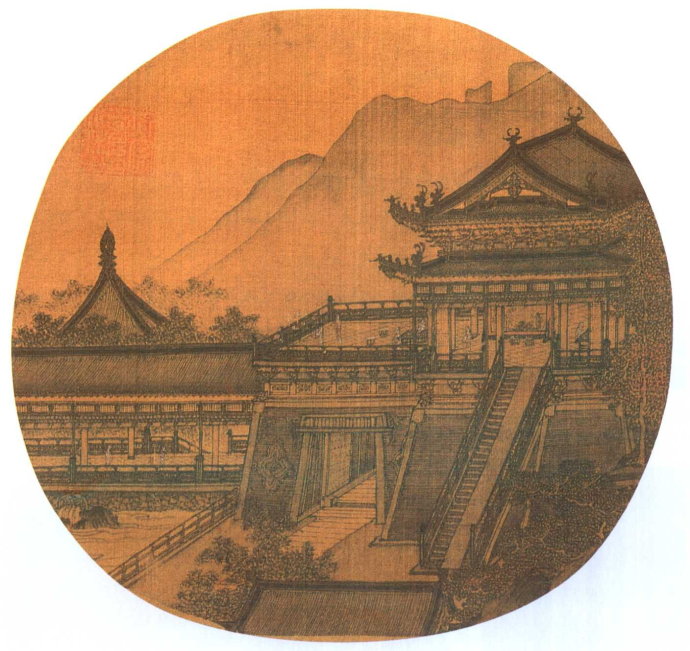

Anonymous, "Qi Qiao Tu" Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, USA

In Tang and Song poetry, women's pursuit of wisdom and skill is frequently mentioned. A poem by He Ning of the Tang Dynasty reads, "The dimming stars are adorned with pearly brilliance, while the palace maids are busy begging for wisdom on the Qixi Festival." According to the "Remaining Stories of the Kaiyuan and Tianbao Periods," Emperor Taizong of Tang and his concubines held banquets in the Qing Palace every Qixi Festival, where the palace maids each prayed for wisdom and skill. However, no paintings have survived. The earliest known painting related to "begging for wisdom and skill" is the anonymous "Begging for Skill and Skill" painting from the Five Dynasties or Northern Song Dynasty, now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the United States. It depicts a banquet held in the courtyard on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month by palace ladies, begging for wisdom and skill. The palace's pavilions are stacked in layers, neatly arranged, and exquisitely constructed. Along the long corridor, several women, some looking up to the heavens, some bowing their heads in silent prayer, some chatting, and some leaning over the railings, face each other with offerings on the tables, devoutly begging the Weaver Girl for wisdom and skill.

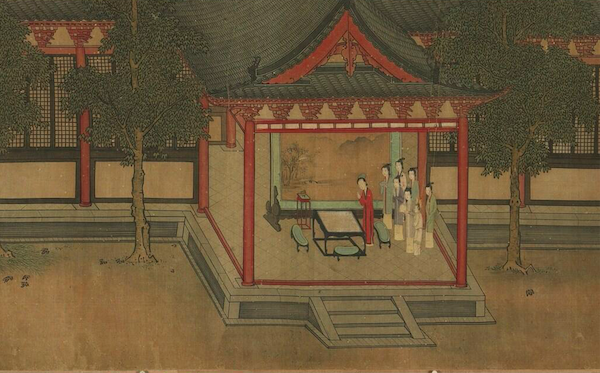

Detail of the painting "Qi Qiao Tu" by an anonymous artist, from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, USA

Qixi Festival in the Song Dynasty: Scenes of Qiqiao in the Palace and Among the People

The Song Dynasty was the heyday of Qixi Festival culture. The "Dongjing Menghualu" records that Bianjing, the capital of the capital, entered a festive atmosphere from the first day of the seventh lunar month. Qiqiao markets were set up in places like Panlou Street, selling "Mohele" clay figurines, Qiaoguo (a type of traditional Chinese cake), and other seasonal items. Emperor Taizong of Song even issued the "Edict to Change the Date of Qixi Festival to the Seventh Day," overcoming the popular custom of celebrating it on the sixth day and strengthening its official status.

Li Song of the Song Dynasty, "Han Palace Begging for Skill" (Page), Collection of the Palace Museum

Paintings from this period focused on depicting the splendor of festivals and the details of folk customs. Li Song's "Han Palace Qiqiao Tu" (a scroll), now in the collection of the Palace Museum, depicts small figures with graceful postures and captivating expressions. The slender figures are typical of the Southern Song style. The square shape of the city gate is also a typical structural form of Song Dynasty architecture. The clear and neat brackets demonstrate the rigorous style of jiehua (traditional Chinese painting). To be fair, jiehua requires strict formality, maintaining scale within established rules without becoming rigid, and the brushwork must be flexible without being arbitrary. Therefore, painting jiehua requires exceptional skill. The meticulous and realistic depiction of the structure of this pavilion, along with the detailed depiction of the interior furnishings and the resulting effect of depth of field, makes this a truly exceptional example of jiehua.

Qixi Festival Scroll (attributed to a Song Dynasty artist)

The National Palace Museum in Taipei also houses a Song Dynasty scroll titled "Qixi Qiqiao Tu," depicting court ladies setting up an incense table, displaying melons and fruits, and threading needles on a terrace to pray for skill. The painting depicts a towering pavilion, maids carrying needles, thread, and fruit trays, while the Milky Way shimmers in the distance, and the faintly visible constellations of Niu and Nv, a star. This painting cleverly blends a cosmic view of the correspondence between heaven and man with secular ritual. The "Mohele" clay figurine featured in "Qiqiao Tu" is often placed in Qiqiao Towers as auspicious offerings to the Weaver Girl, symbolizing fertility and good fortune. This clay figurine is featured on the altar in Qiu Ying's "Qiqiao Tu," reflecting the integration of Qixi Festival items and religious beliefs during the Song Dynasty.

"Sui Shi Guang Ji" quoted "Ti Yao Lu" as saying that "it was a custom in Bian Jing of the Liang Dynasty to use double-eyed needles to pray for cleverness on the Qixi Festival." In the Song Dynasty, a competitive game of "double needles pulling double threads" was developed.

Ming and Qing Dynasty paintings: Qixi Festival themes incorporating literati interest

During the Ming and Qing Dynasties, Qixi paintings reached a high level in both technique and connotation, and incorporated more literati interests and life atmosphere.

The most common form of the prayer during the Ming and Qing dynasties was "Worshiping the Milky Way," also known as "Worshiping the Twin Stars." Tang Yin, Qiu Ying, and You Qiu, two of the "Four Masters of Wumen," all created similar "Qi Qiao" paintings depicting this scene.

Ming Dynasty Tang Yin's "Qi Qiao Tu" fan, collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Qiu Ying, Ming Dynasty, "Qi Qiao Tu" (detail), Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

"Needle Threading on the Qixi Festival" by You Qiu of the Ming Dynasty is a long scroll painting executed in line drawing style. Now housed in the Palace Museum in Beijing, it vividly depicts the ancient folk custom of women threading needles on the night of Qixi Festival, praying for dexterity. It holds both artistic and folkloric significance. The painting is elegant and clear, with a crescent moon looming among the clouds. The artist employs a diagonal composition, skillfully arranging the six women in a corner of a courtyard. On the left, three women sit at a stone table, intently threading their needles. On the right, two women appear to have just arrived, one holding a round fan, the other an object. A third woman approaches slowly in the distance. This arrangement maintains a sense of balance while creating a sense of the flow of time.

The artist's capture of the figures' expressions is particularly exquisite: the central woman nods slightly, her gaze focused on her needlework, her expression focused and serene; her partner gazes sideways, her face filled with anticipation; and the fan-carrying woman on the right, her lips slightly raised, as if she were deeply interested in the Qiqiao activities. Each figure's expression echoes the Qiqiao theme, demonstrating the artist's exceptional ability in characterization.

"Threading a Needle on Qixi Festival" by You Qiu of the Ming Dynasty

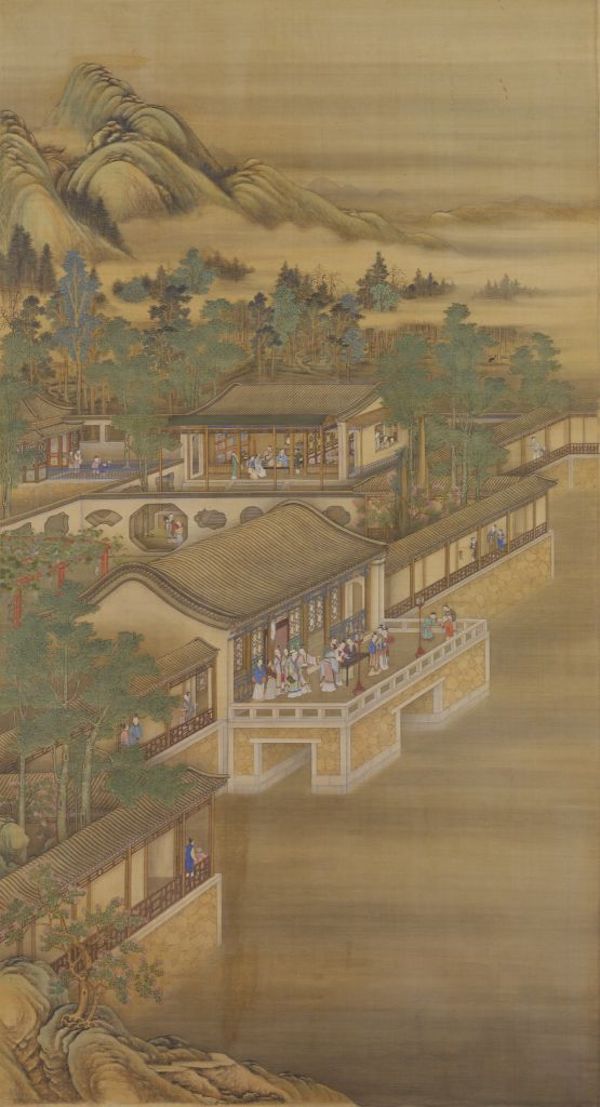

The Qing Dynasty continued to uphold traditional Han festivals, and painters serving in the imperial court during this period also created numerous paintings related to the Qixi Festival. The famous "Yongzheng's Twelve Months of Pleasure" scroll depicts scenes of Qing court activities at the Old Summer Palace during the four seasons. One painting depicts a banquet held by concubines on the terrace on the night of the Qixi Festival. "A Grand View of Qing Dynasty Unofficial History," Volume 2, "Remnants of the Qing Palace: Palace Annual Chronicles (IV)," records that "On the seventh day of the seventh month, sacrifices are made to oxen and maidens, and the palace oversees these events. The beautiful scenery of West Peak is one of the forty scenic spots in the imperial gardens. Qixi banquets, featuring colorful tents and red boxes, were often held there. Emperor Qianlong's poem, "The beautiful scenery of West Peak is shrouded in the smoke of gunpowder, and it begs for a banquet in the new autumn," is a true record of this scene.

The Night of Qixi Festival, "Yongzheng's Twelve Months of Pleasure" (Qing Dynasty), Collection of the Palace Museum

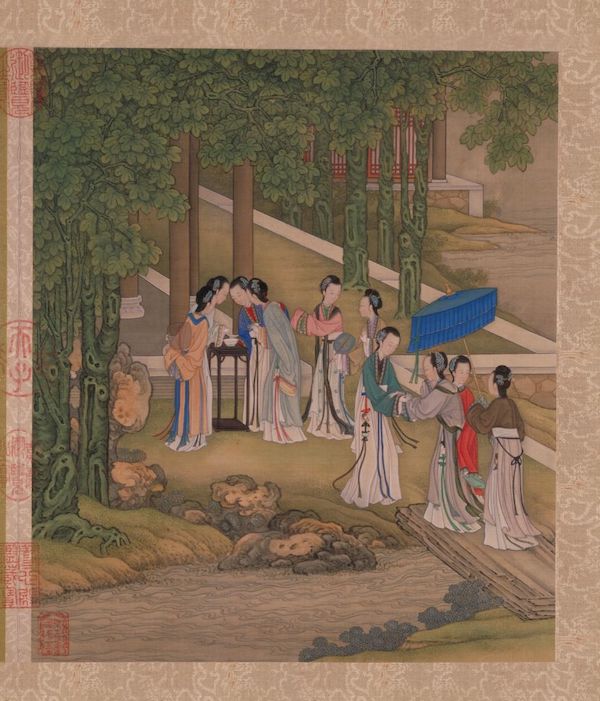

Chen Mei's "Yue Man Qing You Tu Ce" also depicts the "Qi Qiao Festival under the Tong Shade" in July. The painting's vivid and accurate figures and meticulous and rigorous brushwork derive from the Song Dynasty court painting style.

"Qing Dynasty Chen Mei's "Yue Man Qing You Tu" album, "Qi Qiao under the Tong Shade" in July, the Palace Museum collection

In addition, some paintings from the late Qing Dynasty Shanghai School of Painting also feature. For example, Ren Yi's "Qi Qiao Tu Tu" depicts five young women throwing needles around a table, their expressions focused, while a maidservant stands nearby with a fruit tray. The flowing folds of the figures' clothing and the elegant colors vividly capture the solemnity and anticipation of the women begging for skills. Tang Peihua (circa the late 19th century to early 20th century) painted "Cowherd and Weaver Girl" (collected by the National Palace Museum, Taipei), featuring elegant brushwork. A native of Wuxian (present-day Suzhou, Jiangsu), Tang Peihua lived in Shanghai and specialized in figures and women, following the style of Fei Danxu. He was a contemporary of Sha Fu and Qian Huian.

Tang Peihua's "Cowherd and Weaver Girl" in the late Qing Dynasty (Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei)

Kesi silk scroll of the Qing Dynasty, "The Seventh Night of the Seventh Night" (detail), from the collection of the Palace Museum

The Qixi Festival in ancient paintings depicts both celestial legends and a celebration of secular life. It blends the vastness of the Milky Way, the ethereal beauty of the Magpie Bridge, the dedicated nature of needlework, and the piety of begging for dexterity, constructing a romantic universe connecting heaven and humanity. Gazing at the woman threading a needle under the moon, or the immortals gazing across the Milky Way, we hear whispers that have echoed through the ages: the thirst for wisdom, the unwavering commitment to love, and the aspiration for happiness—these have always been the unfading undertones of Chinese civilization.

(Some of the painting information in this article is from the Palace Museum)