In the recent theft of artifacts from the Louvre Museum in France, all nine stolen items were cultural relics from the Napoleonic-Bonaparte dynasty. The emerald necklace and earrings belonged to Empress Marie-Louise, Napoleon I's second wife; the sapphire three-piece set belonged to Empress Hortense, Napoleon I's stepdaughter and mother of Napoleon III; and the crown, pearl and diamond tiara, relic brooch, and lapel brooch belonged to Eugénie, Napoleon III's wife and Empress of the Second French Empire.

Ironically, while the Napoleonic-Bonaparte jewels disappeared from the Louvre, the French art world was immersed in this year's "Napoleon nostalgia wave." The Louvre's exhibition "Jacques-Louis David" had just opened, paying tribute to the greatest painter of the Napoleonic era; and this summer, a rare auction of Napoleonic art concluded at Sotheby's Paris, where 112 artworks with a total estimated value of €3 million ultimately sold for €8.3 million, 2.77 times the estimate.

The three owners of the stolen jewels from the Louvre: Queen Marie-Louis (left), painted by François Gérard in 1807; Queen of Orthames (center), painted by François Gérard in 1813; and Queen Eugénie (right), painted by Winterhalter in 1853.

Why is art from the Napoleonic era so valuable? The Château de Fontainebleau, located outside Paris, houses over 700 pieces of Napoleonic art, including François Gérard's portrait of Napoleon and Empress Josephine in their coronation robes, as well as the coronation sword, formal attire, bicorn hat, and Napoleon's childhood cradle. The Napoleonic era was the adolescence of art and one of history's most passionate periods, conveying a belief lacking in the world today: anything is possible, and everyone has a chance.

The Image of Emperors: The Birth of Neoclassicism

Upon entering the Palace of Fontainebleau, one is greeted by François Gérard's large-scale oil painting, "Napoleon I in Coronation Garment," which reminded me of another Gérard painting of the same name that sold for €736,600 at Sotheby's Paris in June of this year. The auction house unusually did not provide a public valuation for this worthless treasure; the buyer could only obtain an estimate by inquiring privately.

Gérard's painting "Napoleon I in Coronation Garment," sold at Sotheby's Paris in 2025. Image: Sotheby's

Napoleon I in his coronation robes, painted by Gérard in 1805 and housed in the Palace of Fontainebleau. Photograph by Laurachen.

Painting a coronation portrait of Napoleon was a common subject for almost every Neoclassical painter, giving rise to a group of "Napoleon artists": Jacques-Louis David, Jean-Auguste Ingres, François Gérard, Robert Lefève, Jean Gros, and Giraudet Triosson. They romanticized the rebellious acts of the French Revolution, portraying youth as an independent group, rewriting history, and creating a brilliant future.

Jacques-Louis David, *Napoleon I in Coronation Garment*, 1807, Harvard Art Museums.

Robert Lefevere, *Portrait of Napoleon in Coronation Robe*, 1811, Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Triosson, *Napoleon in Coronation Garment I*, 1812, Bowes Museum, London.

The origin of the imperial portraiture can be traced back to Napoleon's propaganda strategy. After Napoleon's coronation in 1804, the new emperor needed an official portrait depicting him in his coronation robes to spread his image throughout the empire. Commissioned by Napoleon, Gérard painted the first version of "Napoleon in Coronation Robes" in 1804. This version was subsequently reproduced in numerous copies for use by members of the royal family, imperial dignitaries, and diplomats. The most famous of these is the one before me, held in the Palace of Fontainebleau. Other versions are scattered throughout Versailles, Les Invalides in Paris, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Pushkin Museum in Russia, the Hofburg Palace in Vienna, and the German Historical Museum in Berlin. The work sold at Sotheby's Paris this year is one of these versions.

Napoleon's throne room at Fontainebleau Palace, built in 1808. Photo: Laurachen

Napoleon's Council Room (Salle du Conseil), Fontainebleau Palace. Photo: Laurachen

Imperial paintings had long existed in European courts, but Napoleon's imperial portraits provided a new paradigm for Neoclassical painters. Unlike the slightly profile angles of the Baroque period, Napoleon always faced forward frankly and openly, his face fully visible from the front. He wore a magnificent robe, consisting of an ivory satin gown and a deep red velvet cloak sprinkled with golden bees, and held a coronation sword inlaid with the famous Regency Diamond. He wore a laurel wreath, proclaimed himself king, and his personal heroism was more worthy of respect than that of generations of nobles. The imperial portrait was no longer about "divine right of kings," but about "legitimacy of power" combined with the constitution and the spirit of the French Revolution.

Turn of the century

The Napoleonic era may seem too distant and abstract for China, both temporally and geographically. However, a comparison with other contemporary historical periods provides a more vivid picture. The French Revolution of 1789 occurred at the end of the Kangxi-Qianlong era in China, specifically the last ten years of Emperor Qianlong's reign. When Napoleon seized power in the Coup of 18 Brumaire in 1799, Emperor Qianlong died in the same year, marking the end of the Kangxi-Qianlong golden age and the beginning of over a century of turmoil in modern Chinese history. Napoleon's reign largely overlapped with the 25-year reign of Emperor Jiaqing of the Qing Dynasty, spanning from the late 18th century to the 1820s.

The Napoleonic era coincided with the Jiaqing reign of the Qing Dynasty. Left: Ingres, *Napoleon I on the Throne*, 1806, Musée d'Arms, Paris; Right: Anonymous, *Portrait of Emperor Jiaqing of the Qing Dynasty in Court Dress*, Palace Museum.

The fin de siècle, or the Belle Époque, is often fondly remembered in the art world, referring to the turn of the 20th and 19th centuries, a period also known as the era of Impressionism. Going back a century, to the late 18th and early 19th centuries, was an even more turbulent time, a period of flourishing Neoclassicism and Romanticism. Eastern and Western history diverged from this point, their positions reversed, and they embarked on different paths. China transitioned from the height of its feudal dynasties to decline, while Europe, for the first time, overthrew its feudal dynasties and embraced democracy and freedom.

Jean Gros, *Napoleon at the Battle of Eau*, 1807-1808, Louvre Museum.

Looking back over 200 years into history allows for a clearer understanding of the awe-inspiring events of the Napoleonic era. While the ancient Eastern empires were basking in lukewarm waters, unaware of the impending crisis, the dangerous and chaotic revolution in France fundamentally transformed Europe's social fabric and institutions. Prior to this, China and the West enjoyed an equal relationship; Emperor Kangxi and Louis XIV, the Sun King of France, fostered a honeymoon period of frequent exchanges, and Emperor Qianlong maintained contact with the Bourbon dynasty through missionaries and trade channels. However, the French Revolution became a turning point in the rise and fall of Eastern and Western powers. Upon learning of the French Revolution, Emperor Qianlong failed to recognize the shift in global trends, instead viewing it as a violation of traditional order, suppressing the White Lotus Rebellion, and intensifying domestic purges and control.

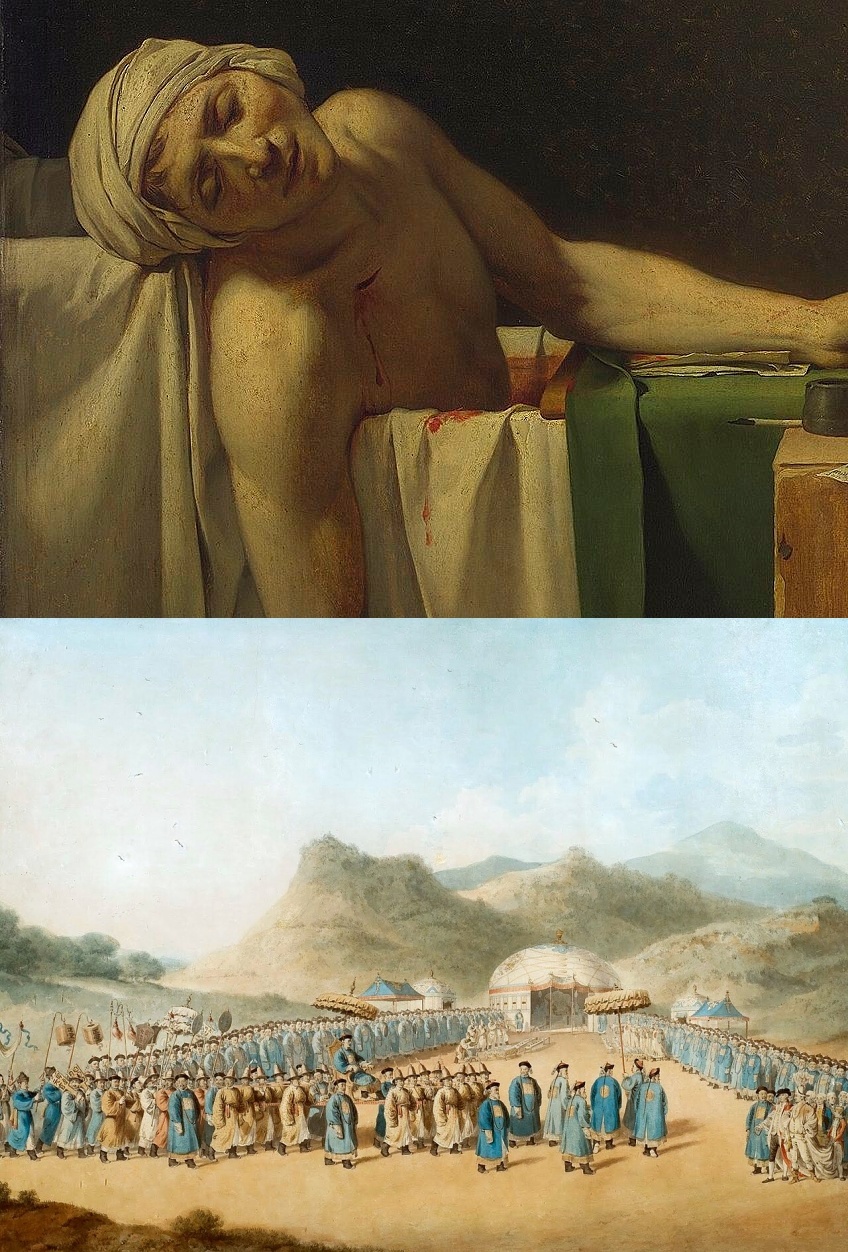

Two paintings depicting the events of 1793: Above: David's *The Death of Marat* (detail); Below: William Alexander's *Emperor Qianlong Receiving the British Macartney Mission*.

Two paintings depicting the history of the East and West in 1793 are thought-provoking. In 1793, Jacobin leader Paul Marat was assassinated. The painter Jacques-Louis David rushed to the scene and painted Marat's portrait, "The Death of Marat," portraying a revolutionary saint who bled for his ideals, highlighting the sublimity of the French Revolution. In the same year, the British Macartney Mission visited China, but due to a dispute over the kneeling etiquette, the Qing Dynasty rejected all British trade requests, missing a valuable opportunity to engage with modern industrial civilization and change its closed-off state.

A piece of royal porcelain made in Prussia in 1805, now in the collection of the Palace of Fontainebleau. The plate depicts the mobilization of the Prussian army, commemorating Napoleon's invasion of Berlin in 1806. (Photography: Laura Shen)

Charles Meunier, *Napoleon Enters Berlin in 1806*, 1810, Palace of Versailles.

The Qing Dynasty, accustomed to the tributary system, was unable to grasp the meaning of a sovereign state, while the concept of a nation-state was a product of Napoleon's conquests. At the turn of the century 200 years ago, Napoleon's conquests awakened the national consciousness of Germany, Italy, Spain, and Russia, and painters Charles Meunier, Goya, and Jean Gros preserved the memory of nation-states through their historical works.

Imperial Style: Antiquity and Innovation

To distance himself from the Bourbon dynasty, Napoleon commissioned artists to create a new style, which gave birth to the Empire style. It abandoned the ornate Baroque and the refined Rococo, and was different from the Renaissance and 17th-century classicism. It took ancient Greece and Rome as its model, embodied the spirit of the French Revolution and the maintenance of the republican system, and pursued classical culture and heroic spirit.

The restoration of the ancient Roman style was the standard for arts and crafts during the Napoleonic era. The image shows an object presented by Napoleon to Empress Marie Louise in 1811 on the occasion of his son's baptism; the relief depicts the birth of a Roman emperor. (Photography: Laura Shen)

Empire-style artifacts featuring the Napoleonic family, housed in the Palace of Fontainebleau. (Photography: Laura Shen)

It is worth noting the portraits of women during the Napoleonic era. Before the French Revolution, women wore high wigs, corsets, and exaggerated crinolines that expanded the volume of their skirts. The liberation of women during the Empire was reflected in their clothing. The Empire dress was a garment that liberated women's bodies. Women no longer wore heavy wigs, removed corsets and crinolines, and raised the skirt line below the chest, presenting a slender figure where "everything below the chest is legs." The waist and legs gained a loose and free environment under the straight skirt.

Gérard's "Empress Josephine in Coronation Gown," Collection of Fontainebleau Palace. Photography: Laurachen.

Marie-Louis, one of the owners of the stolen jewels from the Louvre, is depicted in Gérard's 1813 painting, "Queen Marie-Louis with Her Son."

Jacques-Louis David's style of depicting women also contrasts with that of the Bourbon and Napoleonic eras. In the 1770s, his paintings featured light, bright colors and delicately curved compositions, with playful women dancing in gardens amidst cherubim and mythological scenes of love. By the Napoleonic period, women wore only simple white Grecian-style dresses and flowing shawls, boldly exposing their arms with serene expressions.

Left: Jacques-Louis David, *Mademoiselle Guimard as a Dancer at the Tepsis*, 1774-1775; Right: Jacques-Louis David, *Portrait of Madame Vernac*, 1799, Louvre Museum.

The imperial style was not exclusive to royalty; the novels of British author Jane Austen offer a glimpse into the lives of ordinary people during the imperial era. Works such as *Sense and Sensibility*, *Pride and Prejudice*, *Emma*, *Mansfield Park*, and *Persuasion* were written during the first decade of the 19th century, coinciding with Napoleon's conquests. European society began to abandon patriarchal views, advocating gender equality and promoting respect, understanding, and self-realization.

Gérard's *Madame Périgaud*, 1804, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Jane Austen was an English writer of the Napoleonic era, and her novels are characterized by their Empire style. Above: 1995 British TV series *Pride and Prejudice*; Below: Still from the 1996 film *Emma*.

Austen lived during Napoleon's Empire, which was also the Regency era in England. Social, economic, and political changes had affected all social classes. The marriage and love affairs of rural nobles and young landowners reflected the bourgeois ideas about humanity and humanism after the French Revolution.

The Dawn of Romanticism

Napoleon brought a glimmer of hope to Romanticism in the first half of the 19th century. Young people were inspired by the revolutionary spirit and Napoleon's great achievements. Enlightenment ideas revealed a richer world to everyone. Napoleon, a short man from a remote small-town background, proved to the world that even the most humble youth could achieve lasting glory. The aristocratic world began to crumble, with new ideas and even venture capital dominating. Individualism, relying on oneself rather than family connections, was inspiring. Faced with vast unknowns, aging societies lost their authority, and the times gave the youth a greater advantage.

The imagination surrounding Napoleon permeated the works of Romantic artists, influencing French artists such as Delacroix and Géricault, and inspiring British Romantic painter William Turner and German Romantic landscape painter Friedrich.

Left: Moses, *Napoleon Crossing the Alps*, 1807, sold at Sotheby's Paris in 2025 for 20 times its original estimated value. (Image: Sotheby's) Right: Jacques-Louis David, *Napoleon Crossing the Alps*, 1801, Louvre Museum.

William Turner, *The Blizzard: Hannibal and His Army Across the Alps*, 1812, Tate Modern.

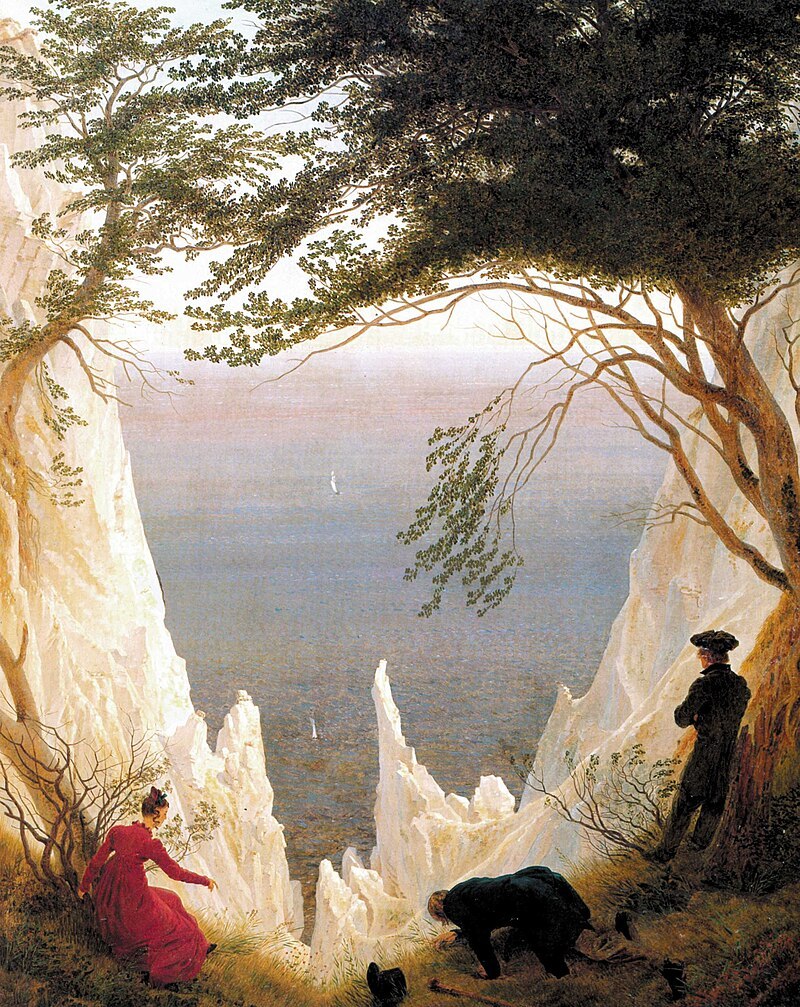

Friedrich, *The Chalk Cliffs on the Island of Rügen*, 1818, Collection of the Winterthur Museum, Switzerland

As Napoleon's army swept across the Alps, the rugged mountains and cliffs inspired the imaginations of Romantic painters. Wilhelm Turner depicted a misty foothills of the Alps; unlike Jacques-Louis David's Napoleon's "man conquers nature," humanity appears exceptionally small before Turner's landscapes and nature. Six years later, the German painter Friedrich, with even bolder imagination, placed a newlywed couple's honeymoon on a seaside cliff in "The Chalk Cliffs of Rügen." The couple faces the steep cliffs and the vast sea; one is filled with fear, the other lost in thought.

Above: Franz Josef Sandmann, *Napoleon on St. Helena*, 1820; Friedrich, *Traveler on the Foggy Sea*, 1818, Hamburg Museum of Art, Germany.

William Turner, *War: Exiles and Stone Shells*, 1842, Tate Modern, London.

In 1815, after Napoleon's defeat at the Battle of Waterloo and his exile to Saint Helena, artists lamented the tragic end of this once-powerful figure. Napoleon's exile on the island became a poignant scene in the eyes of Romantic painters. Friedrich's "Traveler on the Foggy Sea," depicting a figure standing on a cliff, back to the viewer, gazing at a landscape shrouded in thick fog, with ridges, trees, and mountains emerging through the mist, the distant view seemingly stretching to endless horizons, symbolizes contemplation on life's journey and evokes a sense of sublimity. Napoleon also re-enters the realm of William Turner's light and shadow, standing between heaven and earth, enveloped by the vastness of nature in the sunlight, leaving his merits and demerits to be judged by nature and time.

Géricault's *The Raft of the Medusa*, 1818-1819, Louvre Museum.

William Turner, *The Slave Ship*, 1840, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

In a world dominated by abstract art, impressionism, futurism, surrealism, Dadaism, and even AI and electronic art, the realistic, sublime, and romantic paintings of the Napoleonic era are once again stirring our hearts. They are not depictions of an unpredictable future, but rather humanity's authentic past. Napoleon reminds us that youth is not fantasy, but realism and existentialism. So, how long must we wait for humanity's next youth?