The first edition of the Ming Dynasty's *Compendium of Materia Medica*, the flowing calligraphy of traditional Chinese medicine prescriptions, the gourd-shaped bottle embodying the aspiration of "healing the sick and saving lives"... The long-standing tradition of Chinese medicine is not merely a healing art, but a lifestyle permeating people's daily lives. How did traditional Chinese medicine take root in Shanghai? Why did Shanghai become a major center of modern Chinese medicine? On November 22nd, the Shanghai History Museum launched a meticulously planned original special exhibition, "Angelica in Spring on the Huangpu River—Traditional Chinese Medicine and Healthy Living in Shanghai," telling the story of traditional Chinese medicine culture and Shanghai.

The exhibition, organized around the themes of "medicine, pharmacy, and wellness," tells the story of how traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) took root in Shanghai, integrated with Western medicine, has been passed down for millennia, and has become integrated into the lifestyle of modern urban dwellers. Nearly 300 pieces/sets of precious cultural relics and historical documents, including the "Compendium of Materia Medica, first edition published in Nanjing in the 21st year of the Wanli reign of the Ming Dynasty" (on display for only one week), write a biography of "Shanghai-based TCM" for visitors. The three main exhibition areas—"Medicine: Eight Prescriptions of Materia Medica," "Medicine: A Myriad of Miraculous Prescriptions," and "Wellness: Nourishing Life and Mind"—allow visitors to immerse themselves in the unique charm of Shanghai-style TCM.

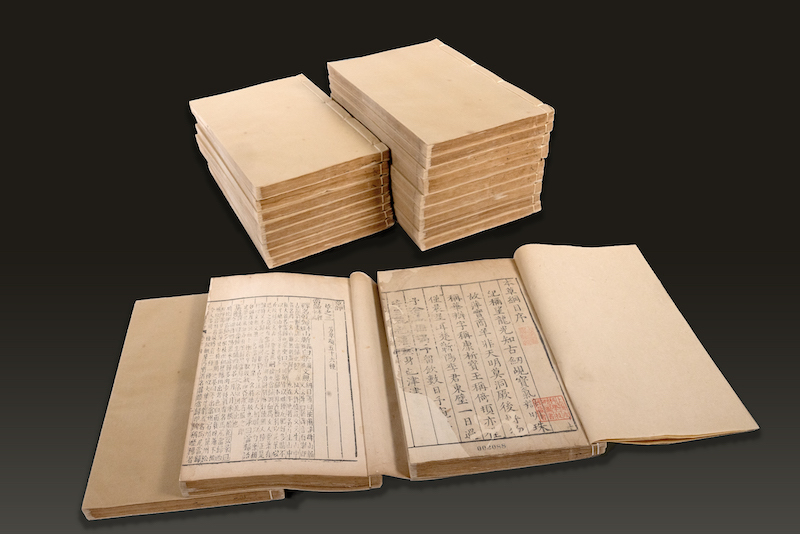

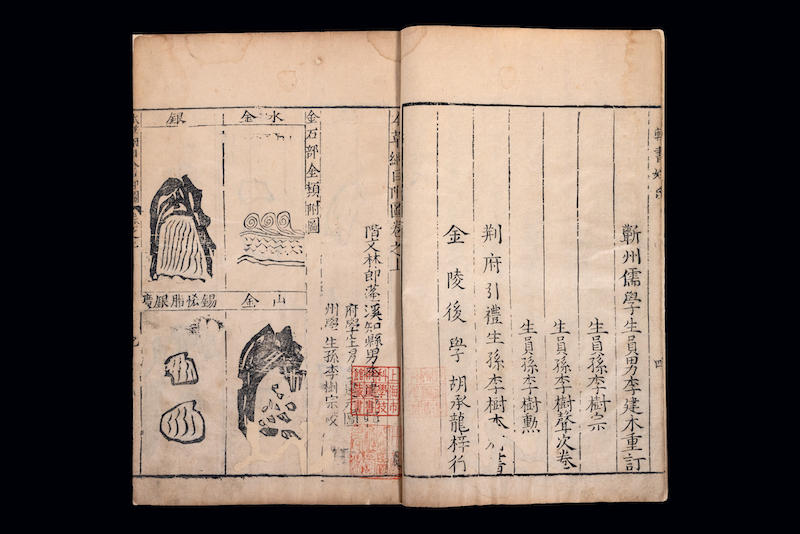

The first edition of the Compendium of Materia Medica published in Jinling in the 21st year of the Wanli reign of the Ming Dynasty (1593) is held in the Shanghai Library (exhibited for one week only). The Compendium of Materia Medica is a medical masterpiece compiled by Li Shizhen, a medical scientist of the Ming Dynasty, over a period of nearly 30 years. The Jinling edition is its original edition, which is the earliest printed edition and the version that is closest to the original work of Li Shizhen.

The first edition of the Compendium of Materia Medica published in Nanjing in 1593 (the 21st year of the Wanli reign of the Ming Dynasty) is held in the collection of the Shanghai Library (exhibited for one week only).

Imperial Acupuncture Bronze Figure, housed in the Shanghai Museum of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The bronze figure is engraved with 14 meridian pathways and 580 small round holes without acupuncture point names. This bronze figure is one of the acupuncture bronze figures commissioned by Emperor Qianlong in the ninth year of his reign (1744) to commend the meritorious officials who compiled the "Golden Mirror of Medicine".

Decoding Traditional Chinese Medicine at Sea from the Perspective of Cultural Relics

“This exhibition is not a popular science exhibition about traditional Chinese medicine, but rather focuses on the relationship between this city and traditional Chinese medicine, and the close connection between them and everyone living in the city. The exhibition especially emphasizes the group of doctors who lived on this land from the late Qing Dynasty to the Republic of China, and how they continuously absorbed modern medical knowledge and integrated Chinese and Western medicine in the tide of the times,” Wang Chenglan, associate research librarian of the Shanghai History Museum and curator of the exhibition, told The Paper.

The exhibition opens by guiding visitors step-by-step into Shanghai's world of traditional Chinese medicine. A late Qing Dynasty map of Jiangsu's water conservancy system depicts the crisscrossing waterways of the Jiangnan region. Combined with historical materials, the first section traces Shanghai's transformation from a major center for medicinal herbs to a national hub since the mid-19th century, driven by population growth and commercial prosperity. During this development, the businesses dealing in ginseng, deer antler, and white fungus separated from traditional pharmacies; while traditional Chinese medicine pharmacies, influenced by Western pharmacies, expanded their operations, resulting in a landscape of numerous large pharmacies.

Authentic medicinal herbs at the exhibition

Realgar Mountain

amber

Plaques, portraits, and genealogies of renowned medical families such as the He family of Jiangnan, the Zhang family of Longhua, the Cai family of Jiangwan, and the Chen family of Qingpu connect the lineage of traditional Chinese medicine in Shanghai. The "Medicine: Miraculous Prescriptions" section introduces the internal and external cultivation of physicians and the situation of famous doctors in modern Shanghai, comprehensively showcasing the explorations of modern Shanghai TCM practitioners in seeking survival, change, and innovation amidst the scientific tide, and the continuous development of Shanghai-style TCM in response to the times. Archives and artifacts from a number of medical schools, including the Women's School of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine and the Shanghai TCM College, as well as academic societies such as the Shanghai Medical Association and the Chinese Medical Association, bear witness to the outstanding contributions of physicians in constructing a new educational and practical system for TCM.

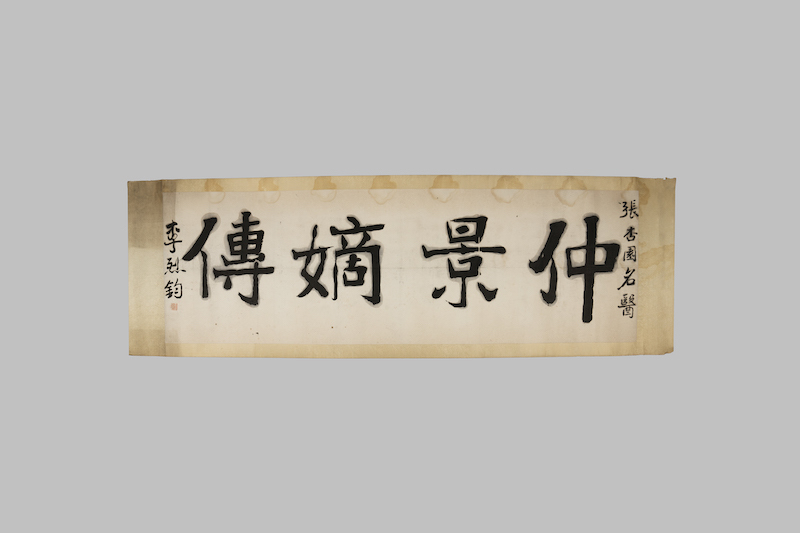

Li Liejun presented Zhang Xingyuan, the 11th generation successor of the Zhang family's medical tradition, with the inscription "Direct Successor of Zhang Zhongjing."

Lu Shi'e's Medical Prescriptions (Collection by Jiang Weiguo)

The exhibition goes beyond simply reviewing history; it delves into the philosophy of health preservation, conveying the message of "from medicine to health preservation" and "inspiring the present from the past." The "Health Preservation and Mind Cultivation" section applies historical wisdom to contemporary life. Sun Simiao believed that a skilled physician is not merely well-versed in the *Huangdi Neijing* (Yellow Emperor's Acupuncture Classic) and knowledgeable about the five internal organs, but should also be well-versed in various schools of thought. This concept is reflected in the exhibition. Objects such as Zhang Xiangyun's purple clay teapot and Hu Pengshou's violin allow visitors to see how renowned physicians throughout history explored various aspects beyond medicine. Artifacts such as Wu Daiqiu's *Chrysanthemums and Crabs by the Fence* from the Qing Dynasty and a begonia-shaped bronze hand warmer from the Republic of China era demonstrate that traditional Chinese medicine's approach to health preservation also involves a balance of activity and stillness, and self-cultivation, advocating a healthy lifestyle philosophy that "the skill extends beyond medicine."

The renowned gynecologist Hu Pengshou's violin was collected by Hu Shiqin.

Why did Shanghai become a major center of modern medicine?

The "Angelica in Huangpu Spring" special exhibition takes the city's history as its starting point to interpret the profound connection between traditional Chinese medicine culture and Shanghai, and why Shanghai became an important center for modern medicine.

The exhibition hall showcases the abundance of products from Jiangnan, including Xu Guangqi's "Complete Treatise on Agriculture" and illustrations of flowers, fruits, and delicacies by renowned Shanghai School painters. Echoing the nearby displays of traditional Chinese medicine pastes, visitors can understand how the concept of "food and medicine sharing the same origin" is reflected in the Shanghai region's winter tonic practices and the consumption of medicinal pastes. For example, the well-known Shanghai City God Temple pear syrup candy, made from ingredients such as snow pears, fritillaria, stemona, and angelica, is decocted, concentrated, and then cut into pieces, bearing many similarities to early medicinal pastes.

Wang Yiting's Copy of Shi Tao's Flower and Fruit Painting

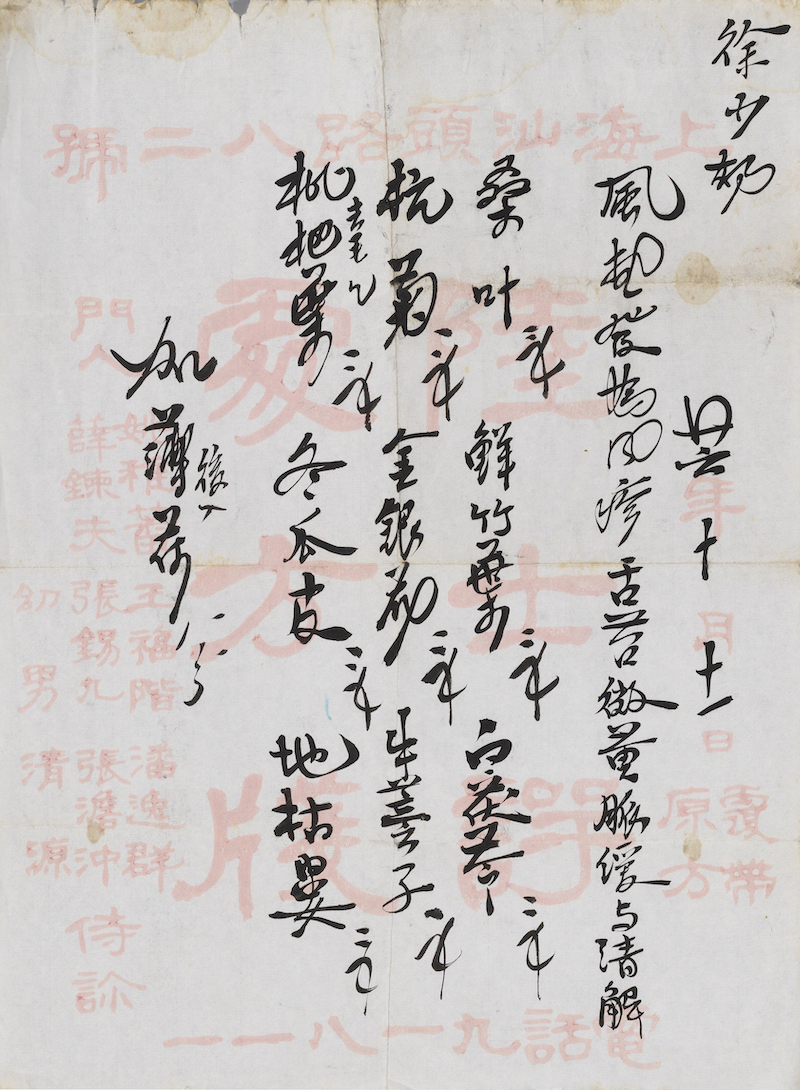

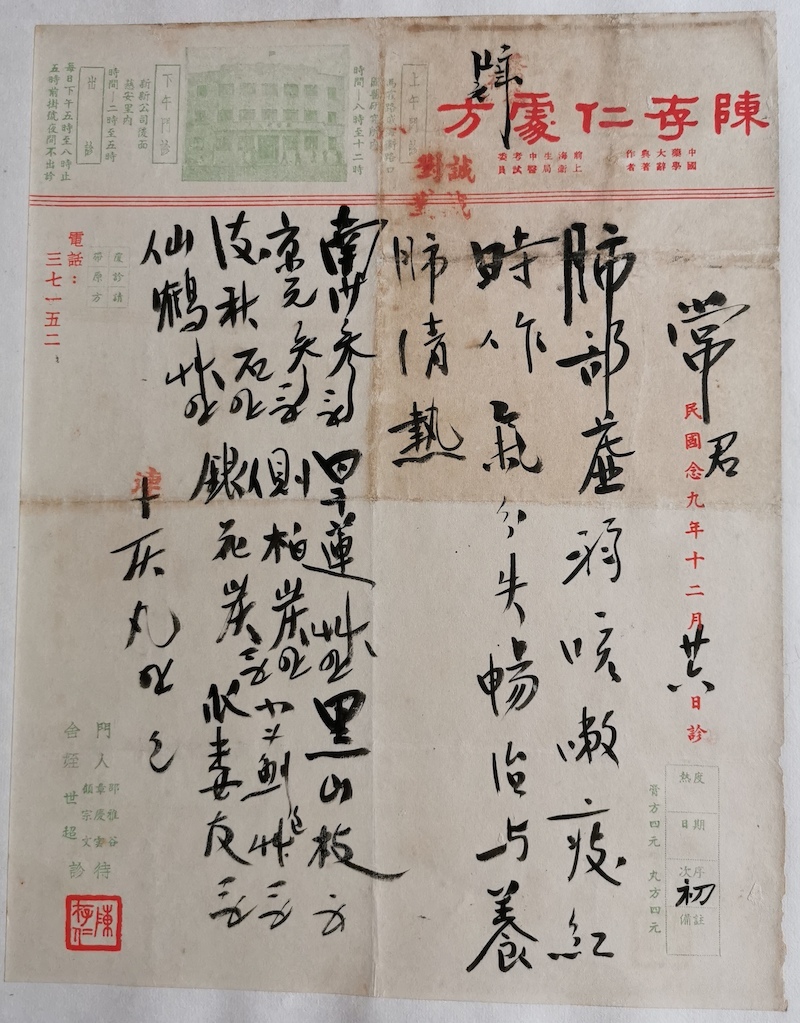

The opening prescription for the herbal paste written by Chen Cunren for Mr. Chang of Tianjin

The Old City God Temple Pear Syrup Candy Cooperative Store in the 1950s

"The exhibition outlines a group of doctors who lived on this land from the late Qing Dynasty to the Republic of China. While inheriting traditions, they also constantly absorbed modern medical knowledge in the face of changing times and the suffering of diseases, integrating Chinese and Western medicine." "Doctors not only practiced medicine to save lives, but they also taught and educated people, founded schools, and cultivated talents. Shanghai's status as a major center of modern medicine is inseparable from this group of doctors," said Wang Chenglan.

The He family of Jiangnan, the Zhang family of Longhua, the Cai family of Jiangwan, and the Chen family of Qingpu are all renowned families of doctors in Shanghai. In addition to local families of traditional Chinese medicine practitioners, the open nature of the city and the ever-changing landscape of the times also attracted many doctors to Shanghai in modern times, making Shanghai a veritable center of modern medicine.

Photograph of the entire class of the 29th grade of Shanghai New China Medical College, 1939. Collection of Jia Yang and Jia Mingxuan.

In 1920, Yu Yunxiu raised the question, "What exactly does traditional Chinese medicine rely on to treat diseases?" This question became a central theme of the debate surrounding the survival of traditional Chinese medicine in the 1920s and 30s. Shanghai's medical practitioners, caught in the tide of the times, offered their own answers. From the novel scenes of "Western medicine treatment" and "oral examination" depicted in the *Dianshizhai Pictorial*, to Yun Tieqiao's declaration of "taking the strengths of Western medicine and combining them to create a new traditional Chinese medicine," and the historical photographs of the Chinese medicine community petitioning in Nanjing in 1929 to "abolish traditional Chinese medicine," the inclusive spirit of Shanghai not only propelled the development of modern Chinese medicine but also enabled Shanghai to play a vital role in the exchange between Chinese and Western medicine.

Posters of Sino-French Pharmacy collected by Shao Yuting

The leather medicine box used by Gu Xiaoyan, known as the "King of Boils," during his house calls is kept at the Tianshan Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital in Changning District, Shanghai.

In addition, the 5th Shanghai Health Consumption Festival (fourth quarter event) and the 11th Shanghai Wild Ginseng Culture Festival opened concurrently on November 22. Using a "curation + festival" model, they vividly presented traditional tonic culture and the unique characteristics of Shanghai-style medicine, promoting traditional Chinese medicine culture closer to the public and serving people's livelihoods. The organizers stated that they hope visitors will not only gain a better understanding of the inheritance and development of traditional culture in Shanghai during the exhibition, but also find their own path to health and wellness through this event.

This exhibition is guided by the Shanghai Municipal Administration of Culture and Tourism (Shanghai Municipal Administration of Cultural Heritage), the Shanghai Municipal Commission of Commerce, and the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (Shanghai Municipal Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine), and hosted by the Shanghai History Museum, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, and Shanghai Association of Traditional Chinese Medicine, with support from Shanghai Shangyao Shenxiang Health Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

The exhibition will run until March 1, 2026.