The 81-year-old painter Xia Baoyuan is a familiar name to generations of Chinese painters. In the far-reaching "sketching movement" of the 1970s, he was an idol in the hearts of countless young students. Chen Yifei's words, "We are all learning from Baoyuan," left a mark on an era.

The Paper learned that the "River of Sketches" five-person exhibition, which was recently exhibited at Jamong Space in the M50 Art Park in Shanghai, is led by Xia Baoyuan's sketches, and also includes sketches by Wang Shengsheng, Chen Weide, Chen Chuan and Yang Zheng.

Chen Yifei (left) and Xia Baoyuan (right) in their youth.

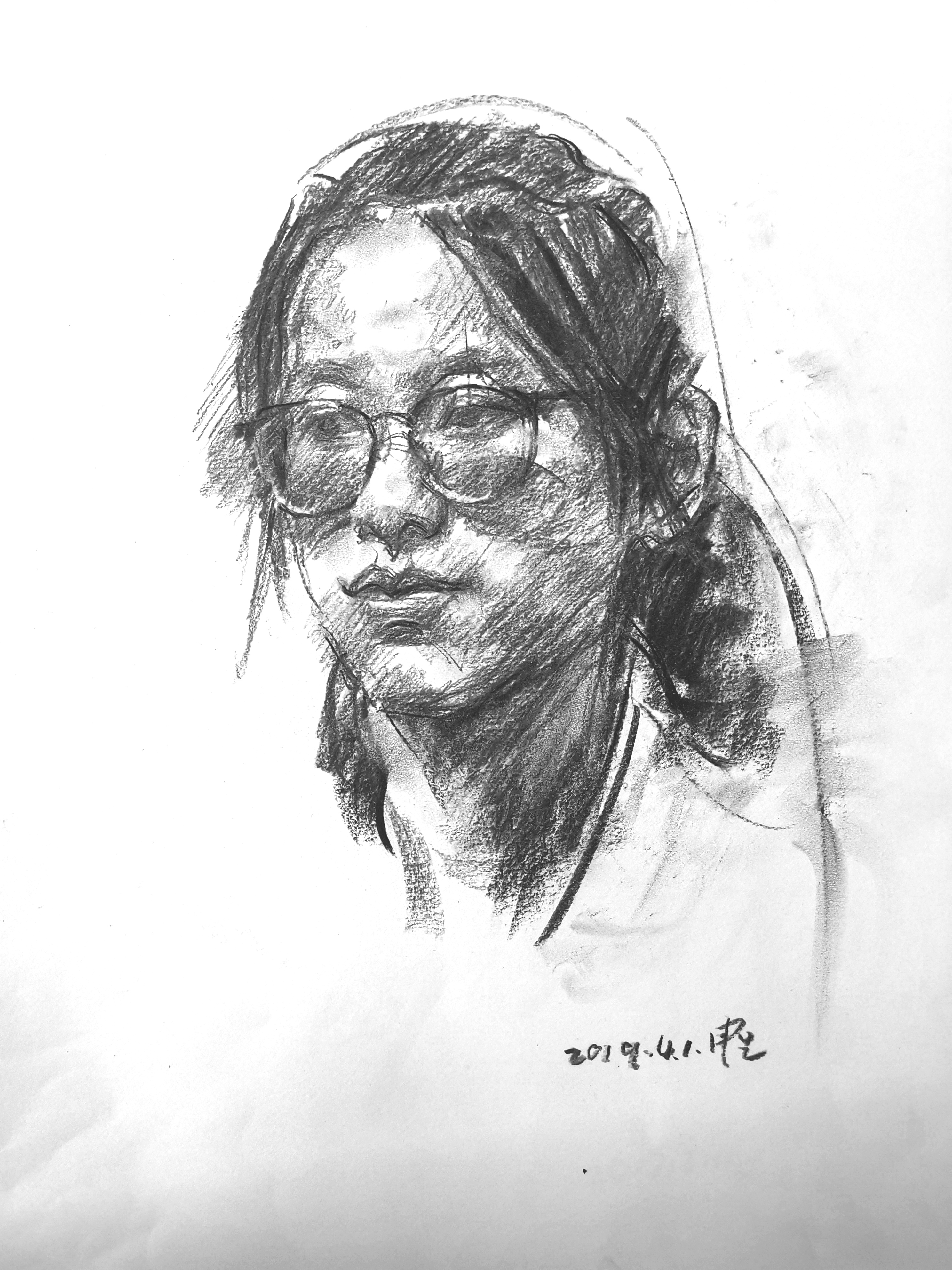

Xia Baoyuan's sketches

In the 1970s, Xia Baoyuan's sketches became a cultural phenomenon, forming what was then known as the sketching movement. His works were reproduced, circulated, and copied through blurry black-and-white photographs, and their influence expanded from Shanghai to the whole country. In addition to Chen Yifei, who stated that he had studied under Xia Baoyuan, the renowned painter Chen Danqing also recalled: "At that time, to be honest, most of the painting techniques were learned from Baoyuan and Jingshan... And the influence of masters who were close to us, whom we had the good fortune to interact with, and who were eight or nine years older than us, was the most crucial and effective for young people."

Curator Yang Jianyong said that Mr. Xia Baoyuan's sketches have influenced generations. Watching Mr. Xia Baoyuan's sketches is like listening to Dvořák's "Fifth Symphony". "He admired Repin's paintings and believed that painting is the reproduction of objective phenomena through visual observation and subjective analysis of the order and relationship of presentation. Understanding and reproduction are the high-dimensional cultivation of the ideal of plastic art, and the study of sketching is the path that best reflects wisdom and cultivation."

Regarding Xia Baoyuan's recent works, he said, "In recent years, I had the pleasure of meeting Mr. Baoyuan again at Wang Shengsheng's studio, and we sketched together. Mr. Baoyuan's observation is very keen. He often makes his first line on a certain point, and after making a decisive stroke, he quickly draws the related auxiliary lines, followed by a large area of gray. In a short time, the structure and space are established. The expressive points are often unrelated to the model's eyes. I have benefited a lot from this. His visual expression often focuses on emotions. He can depict the model's emotions at that moment. Standing behind Mr. Baoyuan and observing the sketching process, I found that Mr. Baoyuan would draw the physical distance between himself and the model."

Exhibition site

According to reports, the planning of this sketch exhibition is also related to the studio of another exhibitor, Wang Shengsheng, in Shanghai's M50. After retiring from the Shanghai Oil Painting and Sculpture Academy, Wang Shengsheng never put down his paintbrush; his weekly figure sketching has become an unwavering ritual. The easel is set up, the model is in position, the charcoal pencil scratches on the paper, accompanied by the hushed discussions and occasional laughter of old friends. Gradually, more and more painters gathered in this studio, and Xia Baoyuan would occasionally join in. This originally private studio has become a scenic spot, a symbol of "persistence built on figurative painting."

Wang Shensheng's sketches

Wang Shensheng's sketches

“The essence of sketching is not a ‘work of art’,” Wang Shengsheng believes. “It is a process of establishing a sense of artistic form through observation, analysis, cognition, and conceptualization.” Here, sketching sheds its veneer as a finished work, returning to its most authentic form of study and exchange. It is this home-like space that has repeatedly drawn back old classmates scattered around the world—Chen Weide, living in France, and Chen Chuan, living in the United States. For them, this is not only a studio, but also a spiritual refuge, a bridge connecting them to the past. The rare tacit understanding and warmth in the exhibition were quietly cultivated in countless sketches in Wang Shengsheng's studio.

The other two exhibitors, Chen Weide and Chen Chuan, are old classmates from the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts. Although they traveled across the ocean, they brought the seeds of sketching to a wider land, where they blossomed into different kinds of flowers.

Yang Jianyong believes that Chen Weide's sketches possess a strong French romanticism. He is obsessed with depicting the changing light and shadow in his living spaces, with his homes in Paris and Shanghai being his eternal subjects. "Objects under the lights at night have a different atmosphere," Chen Weide says. "All colors become superfluous, and the simplicity and purity of black and white become more apparent... The collision between light and shadow is precisely the charm of scene sketching." His studio is not only in front of his easel, but also in his sketchbooks during his travels, where charcoal, pencils, and pens record the flow of life.

Chen Weide's sketches

Meanwhile, across the ocean in the United States, Chen Chuan's feelings towards sketching were more complex and profound. Rationally, he questioned the necessity of sketching from life, believing that artists should "use any means necessary" to achieve their ideas. But emotionally, he was deeply drawn to sketching. "Seeing a good sketch from life gives me goosebumps and makes my heart race," he wrote, expressing a poetic and contradictory sentiment: "Every time I stand before a blank sheet of paper, I seem to see a perfect sketch. With each stroke, it moves further away from perfection. A good sketch is incredibly difficult, seemingly unattainable. I think that's the allure of sketching."

The most touching scene occurred every time he returned to China. "A few of us old men would gather around to look at the sketches. Someone would mutter a few words, and I would look at the painting, look at the person, and we would understand each other without saying a word. Language was no longer important; sketching became our language."

Among the exhibits, Yang Zheng's "Homer in the Window Shadow," the youngest work, is particularly moving because it captures a modern emotion: alienation, nostalgia, and the solitude of quiet contemplation. He prefers to paint plaster casts that are worn and weathered, "I feel they are more human than new plaster casts."

Yang Zheng's "Homer in the Window Shadow"

Wang Shengsheng named his sketching style "All-Factor Painting Sketching." This is a new exploration in the era of high-pixel count, which meticulously refines the order of objects under light, yet it differs from cold "precision sketching," containing the emotional warmth of painting. Yang Zheng said, "Sketching records daily life, a life full of emotion that is constantly being lost."

In today's diverse contemporary art landscape, with its myriad concepts and expressive methods, sketching, the cornerstone of painting, has indeed been forgotten by many. "The River of Sketching" is not a nostalgic elegy. As the exhibition introduction states, "Entering the 21st century, although painting has come a long way and sketching has become more marginalized, we must not forget the way home."

This "river" of sketching originated from the transmission of Western painting in Tushanwan, Shanghai during the Republican era. It flowed through the earnest teachings of teachers such as Meng Guang and Yu Yunjie of the New Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts, formed a torrent in the "era of shining stars" of Xia Baoyuan and Chen Yifei, and was also seen in Wang Shengsheng's studio, in Chen Weide's sketches during his travels in Europe, in the works on display, and in the works of contemporary art students.

(Some of the text and images in this article are from curator Yang Jianyong)