The back of a Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo painting? What will there be? What was revealed?

Where does a work of art begin and where does it end? While canvas has a distinct front and back, it's not that simple with paper. Usually on the back of sketches that are not shown in public exhibitions, those seemingly absent-minded graffiti often record and reveal the artist's truest thoughts. Would it provide a special perspective if the study looked at the backs of paper works in museum collections?

Leonardo da Vinci, Madonna, Child and Cat (front) circa 1478-1481, British Museum © Image: Trustee of the British Museum

The double-sidedness of paper provides space for the development of the artist's ideas. Turning the page allows us to stand in the shoes of the artist and witness the process of creation. On the front of Leonardo da Vinci's painting "The Virgin, Child and the Cat," Maria's leg is a fuzzy swirling structure. On the back, the artist made the placement of the legs more appropriate. But while simplifying the legs, it complicates another area - Leonardo tried three different schemes for the head of the Virgin, and finally chose the far right silhouette with a deeper emphasis. This change puts the heads of the Virgin and Child in a diagonal arrangement, and also changes the relationship between mother and child. Leonardo da Vinci suggested that artists should keep a mirror at hand to observe their work, because unfamiliar images in the mirror make it easier to assess errors in the picture. The front and back of this sketch may be viewed as another way of mirroring.

Leonardo da Vinci, Madonna, Child and Cat (back) circa 1478-1481, British Museum © Image: Trustee of the British Museum

The back of a sketch by Michelangelo shows a fleeting thought in his mind. The obverse of this sketch is a highly finished portrait of Tityus (the giant in Greek mythology). Titus was shot and killed for attempting to rape the night goddess Leto. After entering the underworld, two giant eagles kept pecking at his internal organs. The classicist Jane Harrison noted, "Titus was 'the most vicious criminal' to the orthodox Olympian."

Michelangelo, The Punishment of Titus (front), 1532

But Michelangelo painted the Risen Christ on the back of Titus, with his feet on the lid of the tomb and his hands pointed to the sky. Its outline corresponds to that of the obverse Titus. It is generally believed that Michelangelo first painted Titus and then outlined Christ on the back by means of an outline. But Christ's movement is natural, while Titus is highly contrived, so it's also possible that the artist created the Christ on the back first, and then rotated the paper ninety degrees to draw Titus. But in any case, the flexibility of Michelangelo's imagination can be seen, he sees opportunities in the impossible, and shows the infinite potential contained in double-sided sketches.

Michelangelo, The Punishment of Titus (back), early 1530s

Highly personal, at times spicy and quirky, the backs of the sketches offer a rare glimpse into the artist's everyday life, with recipes, shopping lists, snippets of poetry and more. On the back of the study for The Martyrdom of St. Stephen, Spanish artist Juan de Juanes documents seemingly random details, including the correct proportions depicting St. A Latin motto for love, a recipe for a seasoning, and a graphic illustration of how to measure the distance between banks of a river.

Lucas van Leyden, A Young Woman and the Head of a Man in the Rear, 1519, British Museum, London. Photo: © Trustees of the British Museum

Sometimes the back of the sketch refers to the long and varied life in the studio. A flimsy chalk portrait by Lucas van Leyden shows a late 16th-century hand-drawn sketch with a reptile and half-man, half-fish sea god behind it. These spontaneous conversations seem to run counter to the reverence that people treat these sketches at the moment, but whether it is the value of the artwork itself, or the inheritance and reference of art samples, the sketches are often more lively and lively.

Lucas van Leyden, Half-Man, Half-Mish Poseidon, Young Woman and Boy Head Medal (back), late 16th century, British Museum

Around 1616, as Andrea Commodi (1560-1638) was about to paint the fresco "The Fall of the Rebel Angels" for the chapel of the Palazzo Quirinale in Rome, he reached for the nearest piece of paper, which It happens to be the outer page of a letter. In this "envelope sketch," angels swirl around the address and wax seal on the envelope, presumably the artist saw what was already on the envelope as an architectural element on the fresco. Of the 17 other known sketch studies for Commody's Fall of the Rebel Angel, three are on the envelope. More than four centuries later, when Roger Hilton was bedridden for the last two years of his life, his "Night Letters" to his wife, the painter Rose Hilton, were writing, Wandering between paintings and love letters, the two sides of the paper are an interweaving of art and alcohol, and a shopping list resembling imaginative poetry.

Sketches by Andrea Commody, 1616-1620

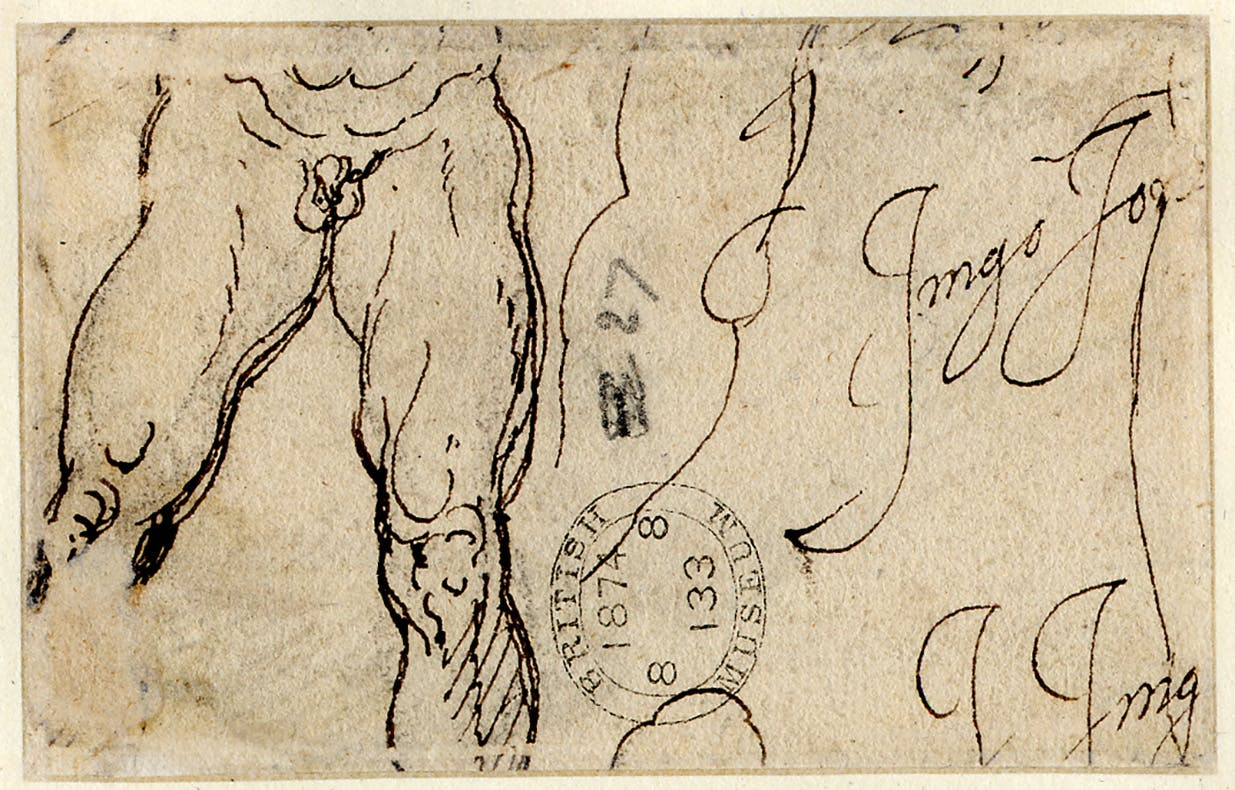

On the back of a study by architect and designer Inigo Jones, there is a written male nude next to the artist's signature. The outline of the muscular knee in the painting echoes Inigo's initial "I" in the signature. Is there any intentional, implied meaning to the composition of this sketch? Unknown now. Whether it's imagining flying, or just testing a new nib, in an art-historical writing that values the relevance of sketches to the finished work, rough sketches like this receive little attention.

Inigo Jones, A Study of the Leg, circa 1573-1652, British Museum

Such sketches, however, are a testament to the power of thinking, and sketches are a space of fun, whether they be nonsense rhymes or thoughtful outlines, and can be an important breeding ground for creative practice. The back of the sketch can contain some revelations, such as the self-portrait of Vincent van Gogh found on the back of The Peasant Woman's Head (1885) in the National Gallery of Scotland; but even the mundane, peek into the minutiae of the artist's daily life is equally instructive .

Note: This article is compiled from the Apollo Magazine website. The author is Isabel Seligman, curator of modern and contemporary art at the British Museum. The original title of this article is "There is no "wrong" side to sketches.