On July 19, 1799, in the seaside city of Rasheed, Egypt, the French were fortifying a castle, and a young officer accidentally found a strange stone buried in the sand, which was densely carved and did not know what it was. symbol or text. At the height of the Napoleonic Wars, no one realized that the stele had great archaeological significance until 1822, when the French scholar Jean-François Champollion (1790-1832) declared it He discovered the secret of the stele: three different types of writing were inscribed on the stele, one of which was the ancient Egyptian script - hieroglyphics. This groundbreaking discovery shocked the world, extending our understanding of the history of human civilization by almost 3,000 years.

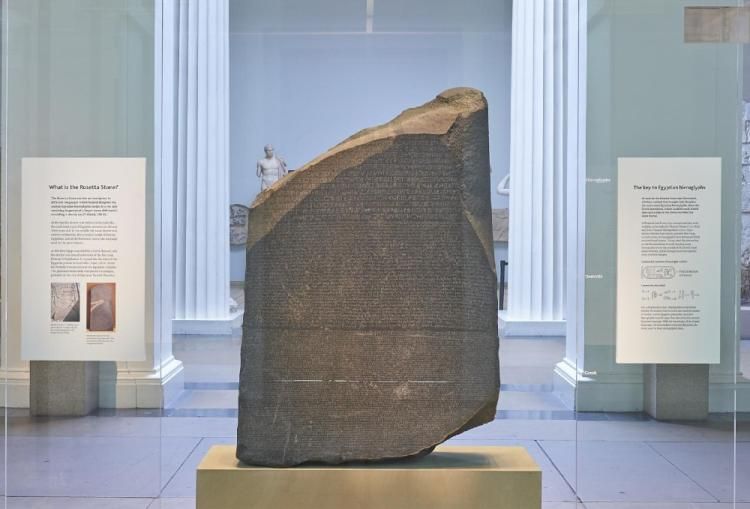

Exactly 200 years after the Rosetta Stone was deciphered, The Paper learned that "Holy Calligraphy: Deciphering Ancient Egypt" is being exhibited at the British Museum. Initial efforts by Renaissance scholars led to more targeted deciphering by the French scholar Jean-François Champollion and the English Thomas Young. At the same time, it will take you to review the various hardships and tests in the process of deciphering ancient Egyptian texts, as well as the enlightenment brought by this breakthrough achievement.

This study of Egyptology is huge. When it was discovered, no one knew how to read ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics. Because the inscriptions expressed the same meaning in three different scripts, and because ancient Greek could still be read by scholars, the Rosetta Stone became an invaluable key to deciphering hieroglyphics, and was of great significance. For this reason, several Egyptian archaeologists have asked the British Museum to return the Rosetta Stone.

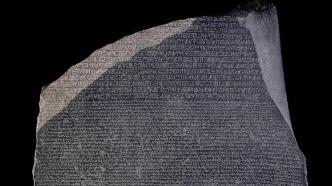

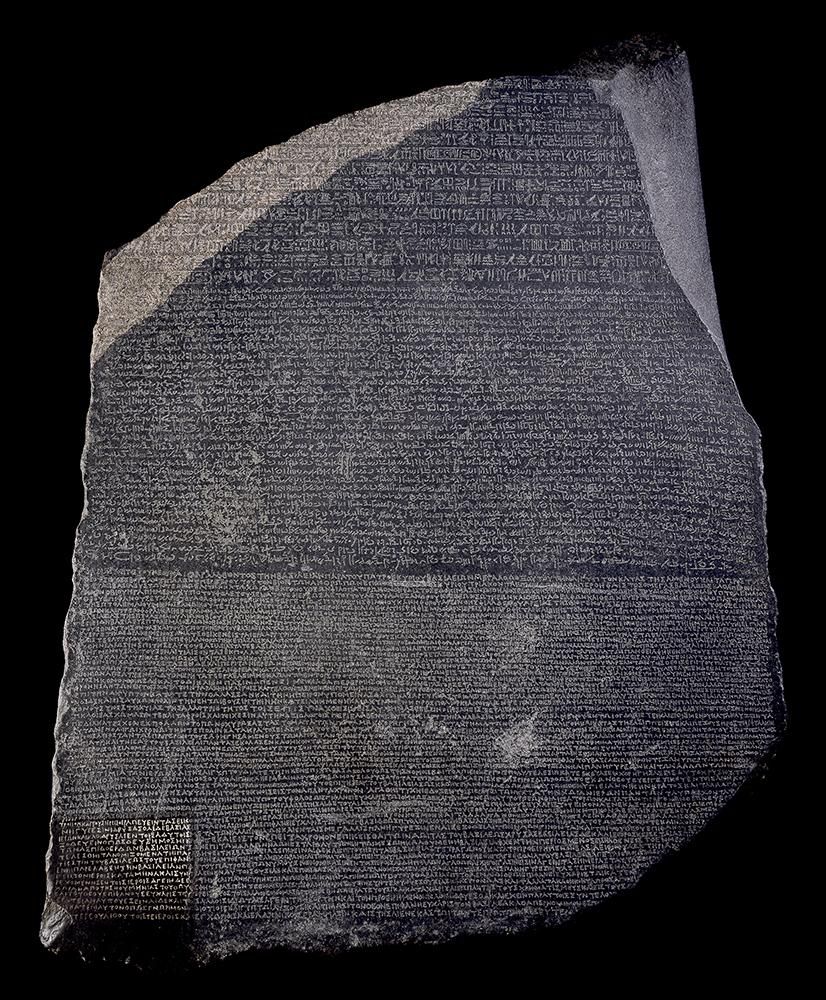

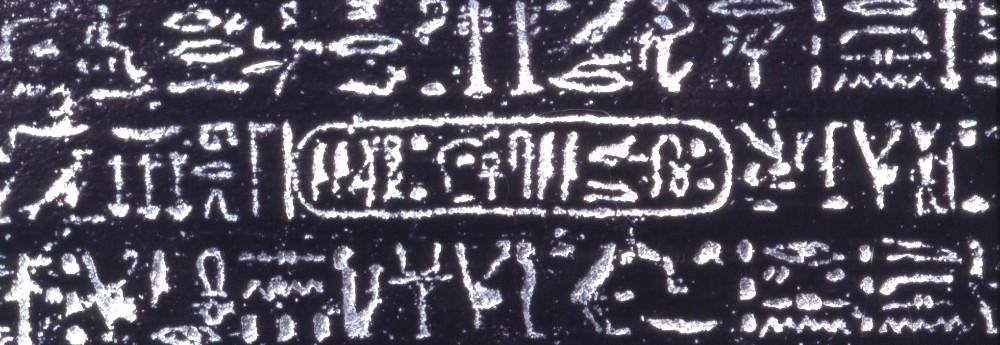

Rosetta Stone, Fortress of St Julian's, Egypt, Ptolemaic period, 196 BC

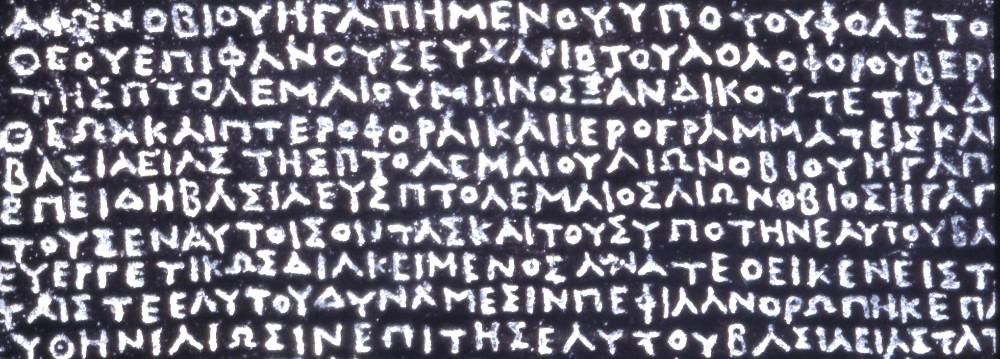

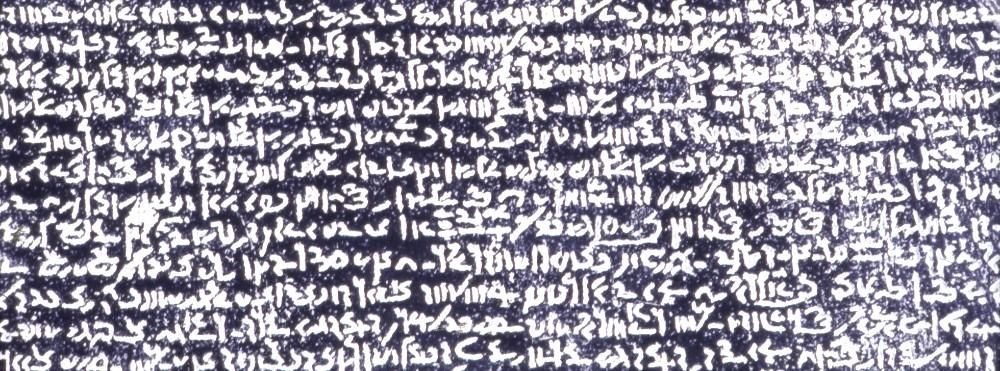

In 1798, the French commander Napoleon (Napoléon Bonaparte, 1769-1821) led an expedition to Egypt. The following year, a "Rosetta Stone" was discovered by the French Expeditionary Force during a project to expand the foundations of the fortress near the Egyptian town of el-Rashid. The stele was erected in 196 BC, with 14 lines of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics inscribed on the upper part, 32 lines of ancient Egyptian cursive script in the middle, and 54 lines of ancient Greek characters in the lower part. It was later verified that these three languages wrote the same thing, which was the edict of the ancient Egyptian pharaoh Ptolemaic V (about 209-180 BC). However, the contents of the inscription were unknown at the time, as the text in it had long since been abandoned.

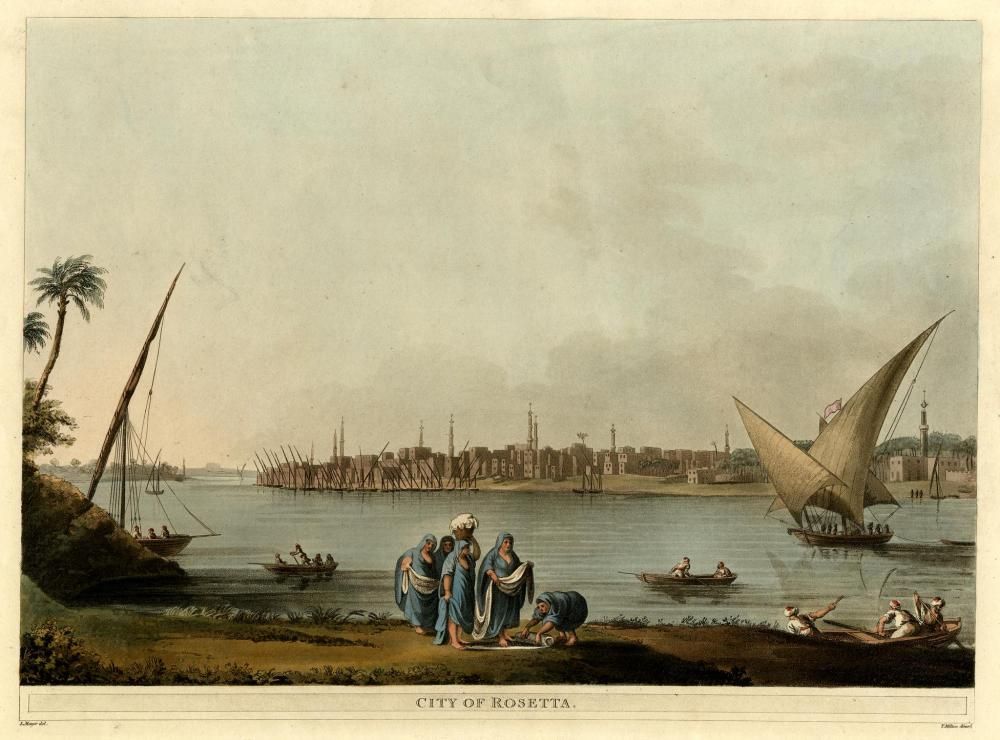

The city of Rosetta when the Rosetta Stone was discovered. Hand-painted watercolor etching by Thomas Milton, 1801-1803.

In the autumn of 1799, Napoleon left behind the army he had brought to Egypt, quietly returned to France, and seized power through the "Bummoon coup". However, in 1801, the French army that remained in Egypt failed miserably against the British and surrendered. The British army seized the Rosetta Stone and shipped it back to England in 1802. Later, King George III donated it to the British Museum in his own name. Since then, the Rosetta Stone was placed in the Egyptian Hall and became the treasure of the town hall.

The Rosetta Stone at the British Museum

The discovery of the Rosetta Stone has attracted the attention and research of many archaeologists and philologists. One of the most influential is the Swedish orientalist Johan D. Åkerblad (1763-1819). ). Oakbride's tutor in Paris was the linguistics and orientalist Silvestre de Sacy (1758-1838). Sassi had already examined the Rosetta Stone and read out the names of five of them. Oakbride continued his work and identified about half of the correct pronunciations from the 29 symbols. However, he mistakenly believed that the hieroglyphs on the stele corresponded to an alphabet. In 1810 Oakbride sent his report to de Sassy for publication, entitled Memorandum: Concerning the Coptic Names of Some Towns and Villages in Egypt. For some reason, however, the publication of the book was delayed, and its official appearance was delayed until 1834. The "Coptic" in the title is a language (Coptic Language), a late form of ancient Egyptian, a combination of ancient Greek and ancient Egyptian, and a unique alphabet. Coptic was gradually replaced by Egyptian Arabic, but is still used today in some ancient traditional churches in Egypt.

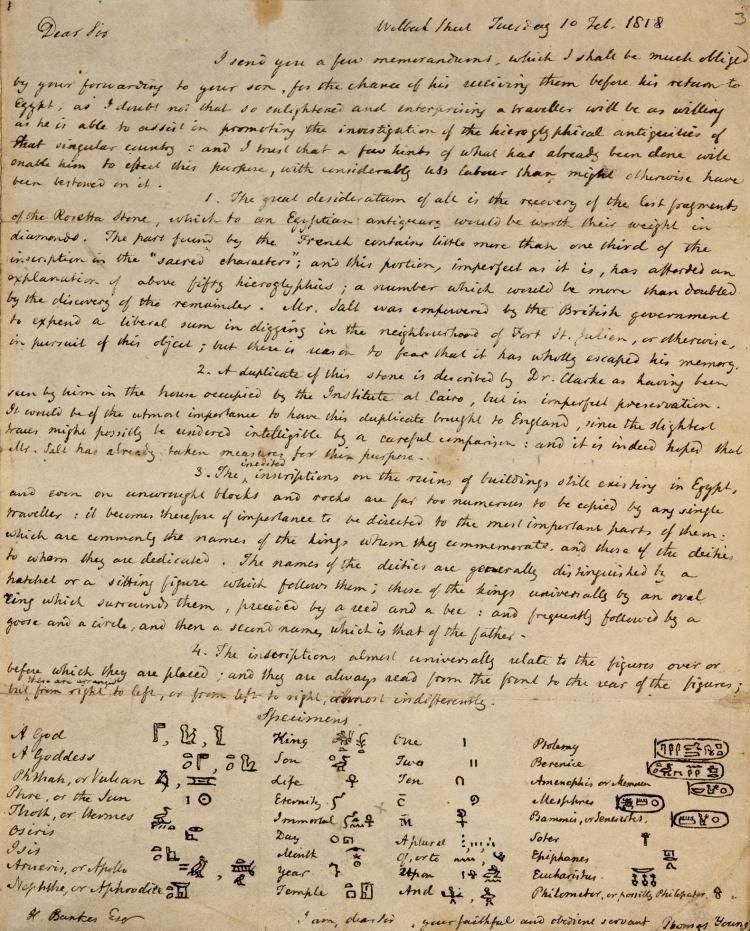

A letter written by Thomas Young on February 10, 1818, asking William Banks to look for examples of these hieroglyphs in Egypt.

A key figure in the deciphering of the Rosetta Stone was the English polymath Thomas Young (1773-1829). Thomas Young started out using Oakbride's alphabet of hieroglyphic symbols. In 1814, he roughly deciphered the inscription using a supplemented alphabet with 86 hieroglyphic symbols, deciphering the names of 9 of the 13 members of the royal family, and also pointed out the correct reading of the hieroglyphic symbols on the upper part of the inscription, which was later published in a book. . Thomas Young was very accomplished in language and writing. He had compared about 400 languages and proposed the classification of "Indo-European languages" in 1813. In 1819, Thomas Young published an important article on Egypt in the Encyclopaedia Britannica, explicitly claiming that he had discovered the basic principles of the Rosetta Stone writing. After Thomas Young's death, posterity inscribed a eulogy on his tombstone: "He was the first to decipher an ancient Egyptian script that no one has been able to decipher for thousands of years."

Next, French scholar Champollion discovered that pictographs have both phonetic and ideographic functions. This statement was initially questioned, but gradually accepted by the academic community. Champollion largely identified the meaning of most phonetic hieroglyphs and reconstructed much of the grammar and vocabulary of Ancient Egyptian. He played an important role in the history of human writing.

Thomas Young communicated with Champollion, but the story was dramatic. In 1814, Champollion published Egypt under the Pharaohs in two volumes. That same year, he wrote to the Royal Society asking for a better interpretation of the Rosetta Stone. Thomas Young, who was the secretary of the society at the time, was not happy when he received the letter, and made a negative reply the following year, saying that the French proposal was not much different from the existing British version. It was Champollion's first knowledge of Thomas Young's study of ancient Egyptian writing, and he realized that he had a strong competitor in London. Since then, their investigations and research work have been kept secret from each other, and there has been no correspondence.

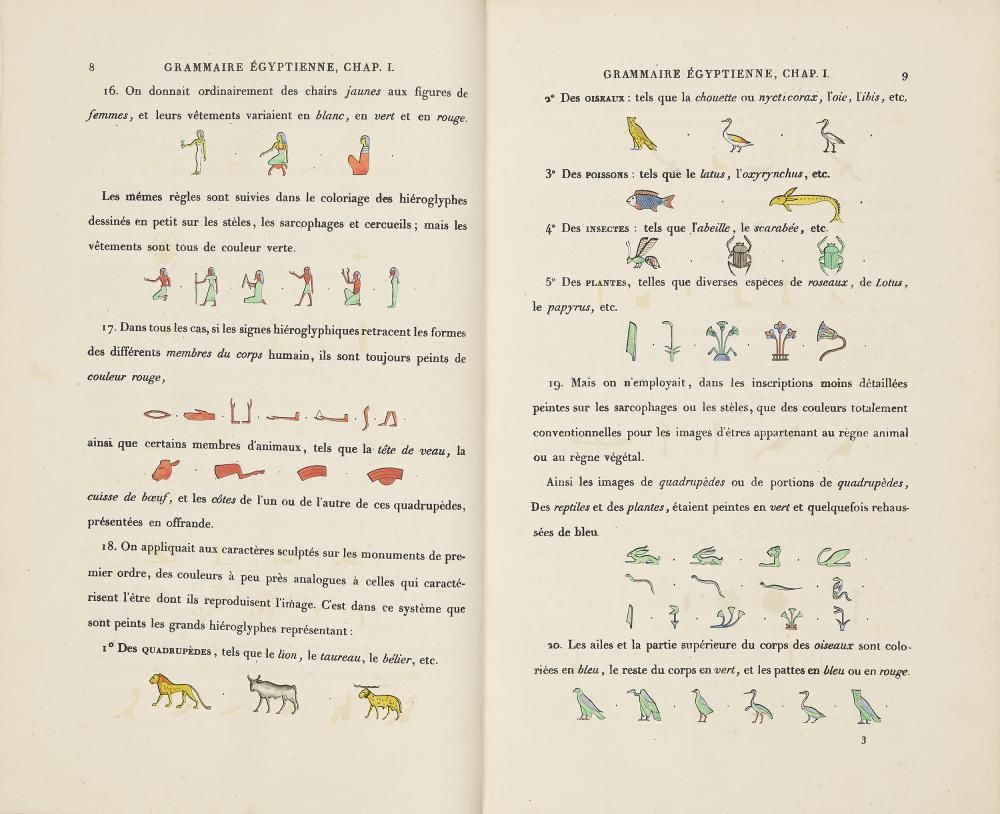

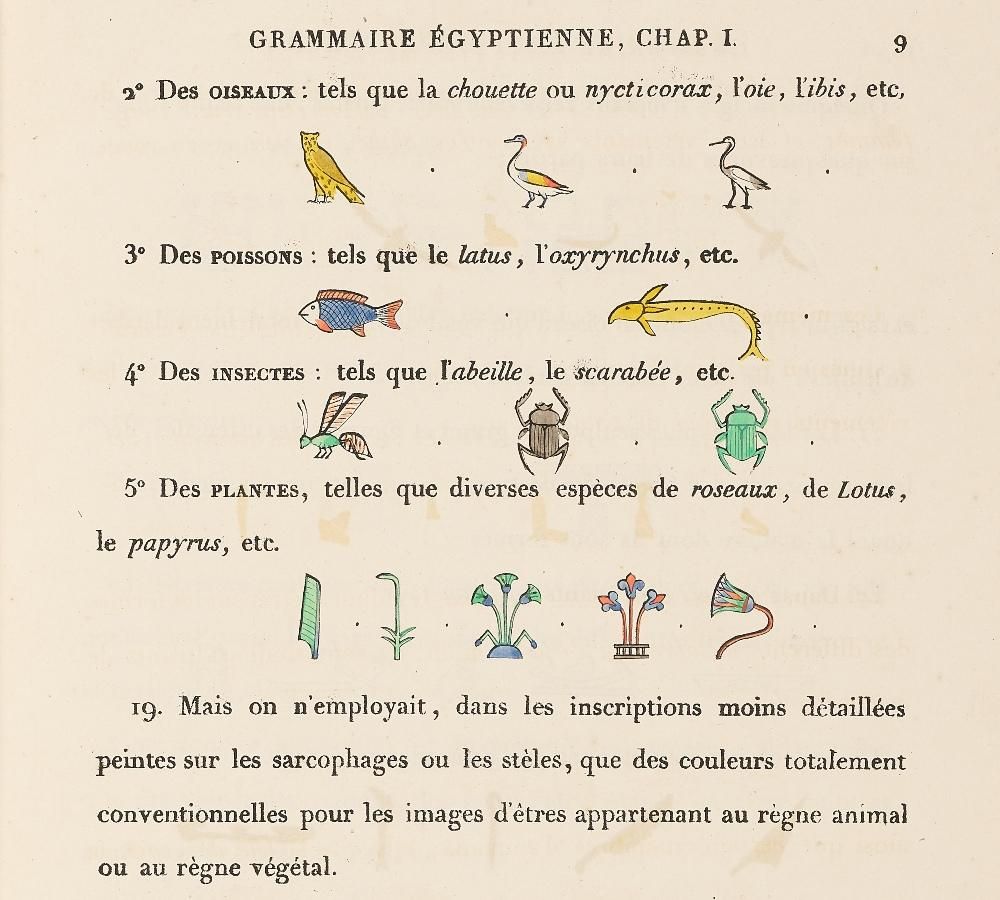

Champollion's Grammar of Egypt, printed edition with hand-coloured hieroglyphs, 1836, Paris, France.

Champollion's Grammar of Egypt, printed edition with hand-coloured hieroglyphs, 1836, Paris, France.

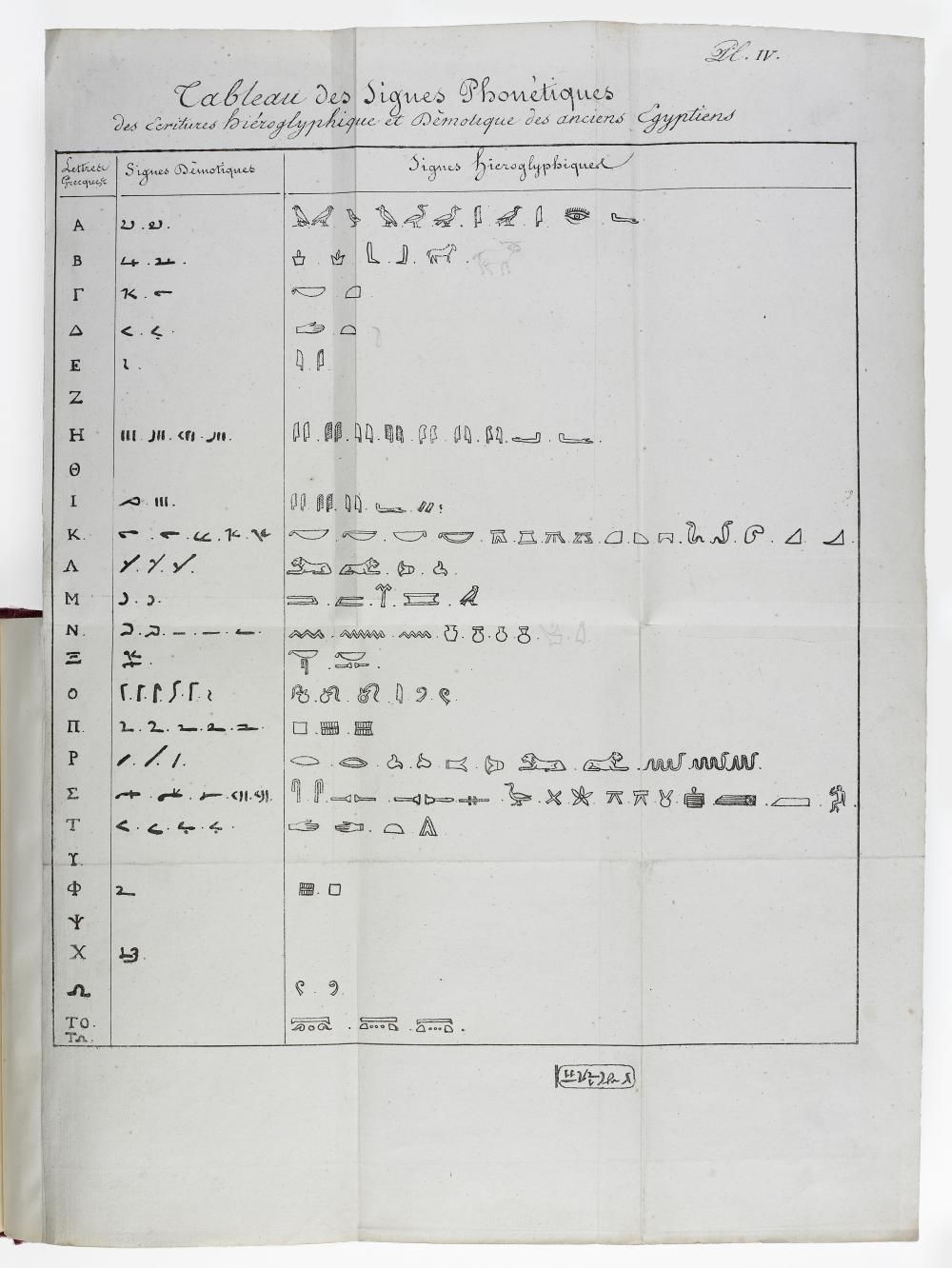

Letter from Champollion to M Dacier on the Phonetic Hieroglyphic Alphabet, Paris, 1822.

In fact, Champollion began to study the Rosetta Stone as early as 1808 through Abbé de Tersan's rubbings. In 1822, Champollion officially published a comprehensive study of the translation and grammatical system of hieroglyphics. In his "Letter to Dacier on the Phonetic Hieroglyphic Alphabet" to Bon-Joseph Dacier (1795-1833), President of the French Academy, he systematically reported the results of deciphering the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone. He wrote: "I believe that long before the Greeks came to Egypt, the same phonetic symbols were used in their hieroglyphs to denote the pronunciation of Greek and Roman proper names, and that these reproduced sounds or pronunciations Consistent with the scroll decorations previously carved by the Greeks and Romans. The discovery of this important and decisive fact is entirely based on my own study of pure hieroglyphics." Like many of his colleagues, Thomas Young also publicly praised his work. However, Thomas Young is said to have subsequently published a report on new discoveries of hieroglyphic and ancient Egyptian writing, and suggested that his work was the basis of Champollion's research.

With the death of Thomas Young in 1829, followed by the death of Champollion in 1831, the deciphering of the ancient Egyptian script stalled. However, by the 1850s, the ancient Egyptian script was basically sorted out.

Detail part of the hieroglyph

ancient greek detail

Plain text section details

From the Rosetta Stone, it is a fragment of an ancient stone tablet with the decree written on it. On March 27, 196 BC, the influential priest of a temple in Memphis, Egypt, conferred the sacred honor on King Ptolemy V (reigned 204-181 BC) in exchange for his good deeds to the country. It is one of many steles showing the decrees set up in all the important temples in Egypt. For broad understanding, the decree is divided into three scripts: hieroglyphic (applicable to priest decrees), colloquial (meaning "language of the people"), and ancient Greek.

Exactly 200 years after the deciphering of the Holy Book, "Holy Book: Deciphering Ancient Egypt" is on display at the British Museum, with a special exhibition showing the entire history of the deciphering of the Rosetta Stone—from medieval Arab travelers to the Renaissance Scholars' initial efforts have led to more targeted deciphering by the French scholar Jean-François Champollion and the British Thomas Young. At the same time, it will take you to review the various hardships and tests in the process of deciphering ancient Egyptian texts, as well as the enlightenment brought by this breakthrough achievement.

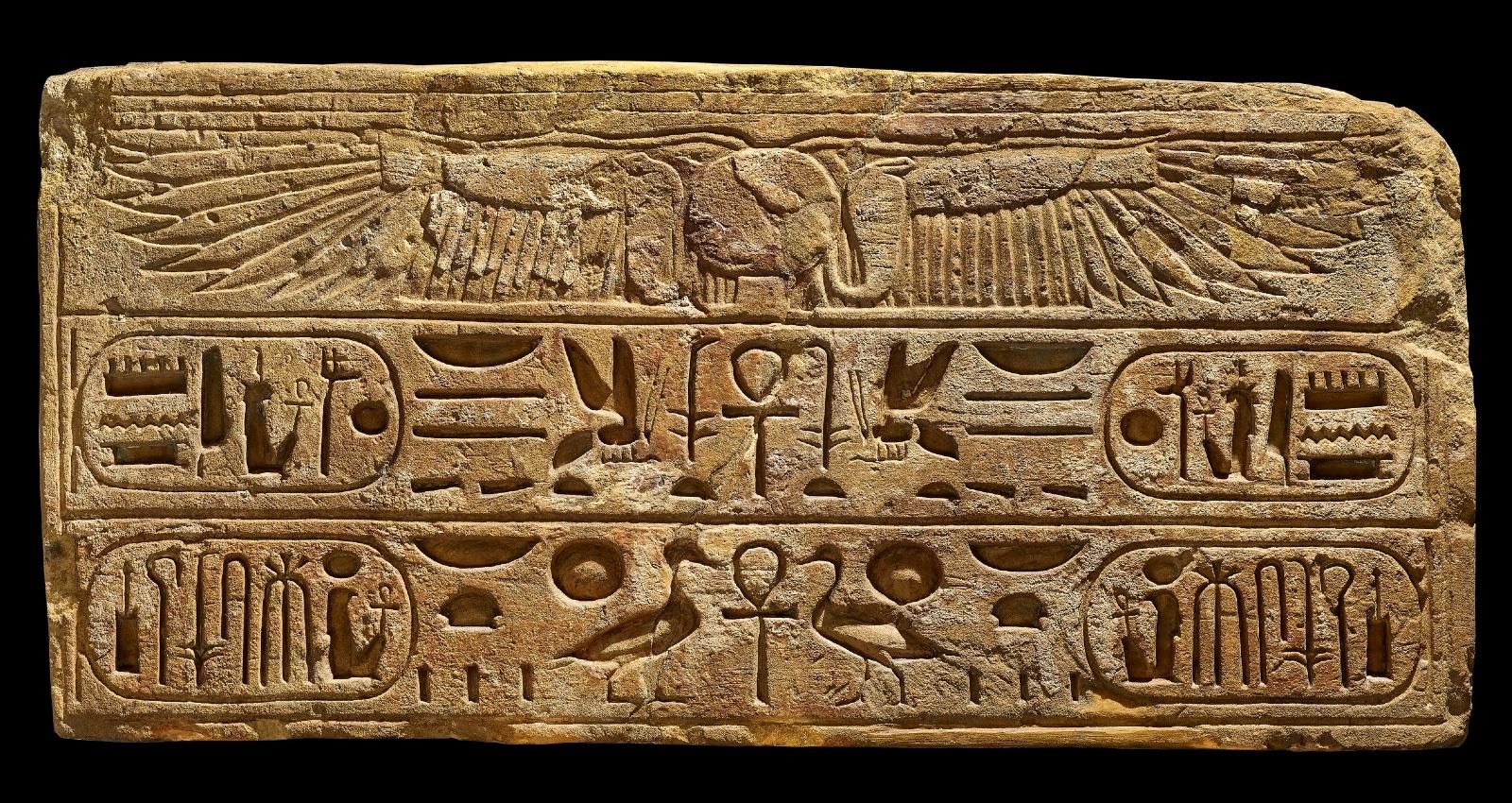

The lintel of the temple of Amenhotep III, found in present-day Fayoum, Egypt, Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt (1855 BC – 1808 BC)

Aberluit's mummy bandage, linen, Egypt, Ptolemaic period, 332-30 BC.

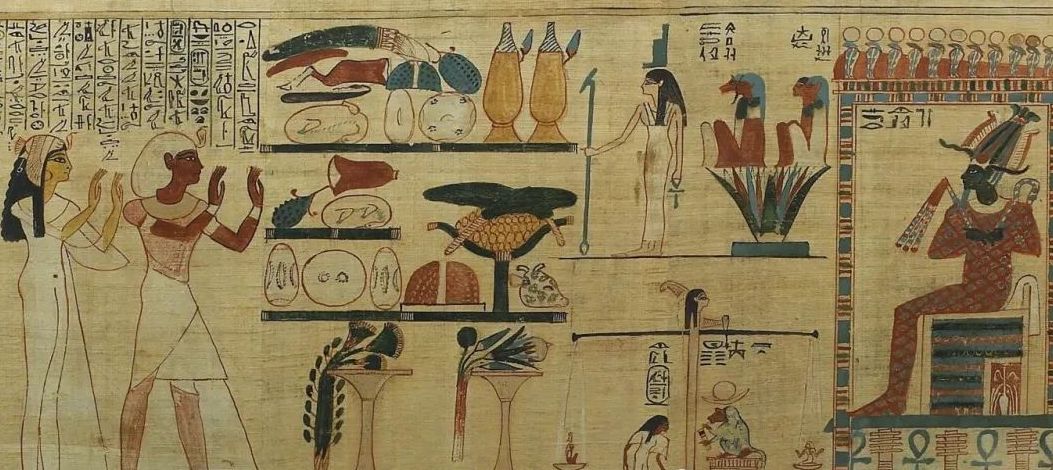

Queen Nojimet's Papyrus Book of the Dead, Egypt, 1070 BC

"Magic Disc". The sarcophagus of Hapumen, black granite, 26th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, 600 BC.

Mummy portrait of Lady Baktenhoe. Egypt, late 22nd Dynasty, 945-715 BC. Licensed by the Northumbria Natural History Society.

Important relics on display include the lintel of the temple of Amenhotep III, Queen Nojimet's papyrus book of the dead, the "Magic Disk", Aberluit's mummy bandage, Ameni Maupe Royal Cubit, Mummy Portrait of Lady Baktenhoe, etc.

It is reported that the exhibition will last until February 29, 2023.

(The graphic and text of this article are combined from the British Museum and the article "Champollion - The Genius Who Rivals Thomas Young".)