Albrecht Dürer's artwork is both traditional and modern. The Renaissance printmaker and oil painter was born in Nuremberg, Germany in 1471 and died there in 1528. His creations are filled with medieval saints and monsters, wildlings in the forest and castles on hilltops—familiar but tingly unsettling images.

The Paper learned that the newly launched special exhibition "Dürer's Material World" at the Whitworth Art Museum in Manchester, UK, is the first major exhibition of Dürer's prints in the museum's collection for more than half a century. The exhibition links the works with Dürer's time and place, inviting the audience to interpret the daily life in Germany 500 years ago from the perspective of the "material world". The curator believes that encountering these prints makes us feel that although we have an irreconcilable time distance with Dürer, we can still be so close.

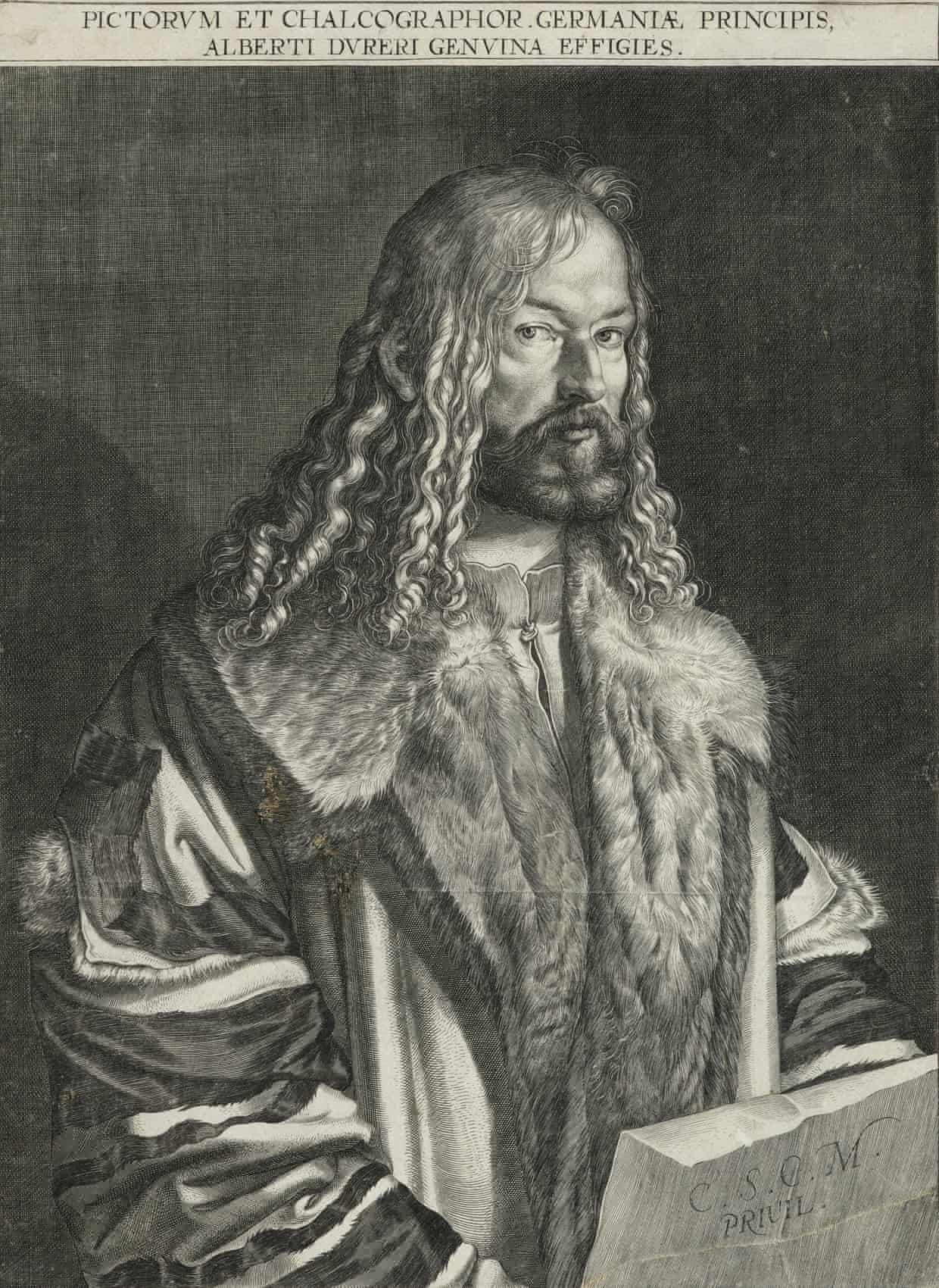

Portrait of Dürer by the German etcher Lucas Kilian, 1608

Composed 80 years after Dürer's death, it reflects his enduring fame. Dürer's understanding of the new technology made him famous, not the first printmaker, but the first to be famous for it.

Since ancient times, industrialists have a tradition of buying and collecting art. When textile magnates in Manchester began collecting Dürer's prints in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they felt the sense of innovation in their works. Just as Dürer adopted new techniques in the field of printmaking, the Manchester factory owners prided themselves on being at the forefront of the manufacturing process.

It was these collectors who established the Whitworth Art Gallery in 1889, and the artworks they owned became the cornerstone of the museum's permanent collection, including many of Dürer's woodcuts, etchings, works that constitute "Dürer's Substance The World" is the subject of the exhibition.

Installation view of Dürer's Material World at the Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester.

"Dürer's travels and connection to nature have been intensively studied over the years. This exhibition focuses on objects that figured prominently in his life and work." Exhibition co-curator Edward H. Walker said.

In the exhibition, Dürer's engravings are displayed alongside the many objects he depicted: from books, hourglasses, compasses, textiles, ceramics, clocks and furniture, to armor and scientific instruments. Dürer depicted the "real" world of objects with an almost hallucinatory precision. Dürer reflected his own fascination with these objects with a masterful engraving technique.

Dürer's family moved to Nuremberg from Hungary. As the son of a goldsmith, Dürer was naturally close to the mastery and application of technology. Dürer began to study and live after he was 15 years old. He studied painting and woodcut with Waghamot. The most important study tour experience was two trips to Italy, during which Dürer met the painters Giovanni Bellini and Raphael. At the same time, he studied Da Vinci's works and art theories, and got in touch with and learned the style of thought of the Renaissance. Since then, science, trade, and philosophy have intersected in his life and art.

Dürer, Great Wealth (Nemesis), circa 1501 The goddess holds a golden Nuremberg goblet similar to those designed and produced by Dürer's father's shop. Depictions of such extravagant items advertised not only his father's business, but his own ability to display luxury as well.

Dürer had a keen eye for new technologies in print production. He believes that oil painting only constructs a single object, but prints can be everywhere, and he uses the popularity of prints to promote himself. Equally astute about ownership of his work, he is said to have litigated early intellectual property lawsuits, and the "AD" monogram is now one of the most recognizable symbols of his era.

Dürer also designed his own shoes, and there is a drawing in the exhibition, cut to the shape of his foot, with precise instructions for the shoemaker and a drawing of what the shoe would look like. Although, this combination of design, production, marketing and ultimate profit is very attractive to the business world. But it all boils down to art—Dürer's depiction of the physical world around him.

Dürer, St. Jerome in His Study, 1514 Dürer added depictions of everyday objects to traditional Christian imagery, bringing myth into the immediate realm. Here the Latin translator of the Bible is surrounded by the latest brass candlesticks and furniture produced in Nuremberg at the time.

From common tools like scissors and drinking vessels to instruments for calculating planetary motion, Dürer's work evokes a sense of both familiarity and wonder. In the etching "St. Jerome in the Study", Dürer carefully designed the work space - St. Jerome concentrated on his desk, an inkwell in the alcove, and an hourglass next to the hat hook , the benches are lined with books and cushions, while two large windows bring plenty of light into the room.

Dürer's precise control over engraving and metal panels created this cozy wooden room, which he then covered and printed with ink. Although there are a few exquisite sketches in this exhibition, most of the works are prints on paper, which contain the magical world of microprinting.

Dürer, Melancholy I, 1514

Hourglasses, dividers, scales, rulers, etc. reflect the world in which people's lives are increasingly affected at that time, and the accuracy of time and measurement is its expression.

Delicate etchings on metal, woodcuts with a deliberately rougher effect, and some experimental, acid-etched rich tones, like the later Impressionists. For example, in "Desperate Man", a naked man covers his face and pulls his hair, making people feel that he is suffering; while other depressed men are brooding, and a woman is unconscious.

Dürer, Desperate Man, circa 1515

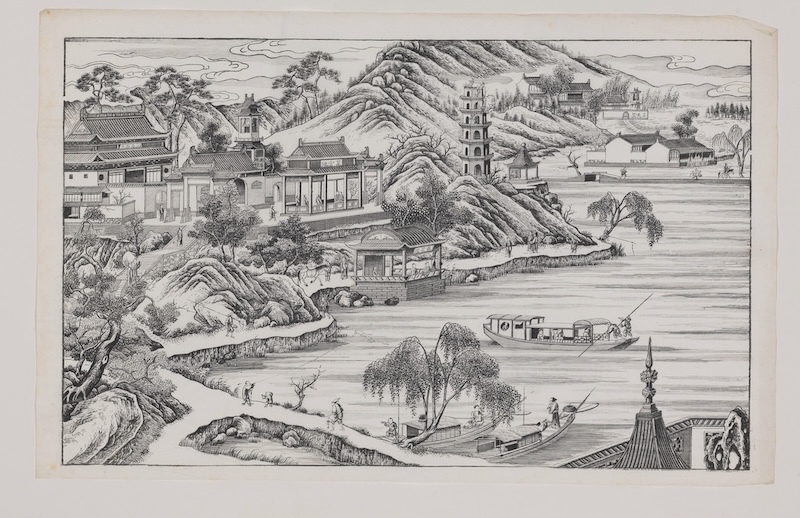

Perhaps, we in our time are more arrogant about art than Renaissance Germans, and we cannot escape our reverence for oil painting. But for Dürer, art was a form of communication rather than a narrow luxury, and he was not the first European artist to use printing. In China, printing has a much older history. When it became popular in Germany in the 15th century, it was discovered that it could reproduce words and images. In particular, when Dürer burst out detailed and complex images, he pushed the exploration of this medium to the sublime in an unprecedented way— —In Madonna and Child in the Meadow, the mother is fondling her baby, but your eyes wander to the little blade of grass behind her.

The more detailed, the more expressive. In this vignette, the blank space behind the weeds expresses the power of nothingness, a modernist idea that, while drawn from the Eastern tradition, was first employed in Europe by German Renaissance printmakers.

Durer, Madonna and Child on the Meadow

More nothingness makes people feel lost. In "Knights, Death, and the Devil," a man in plate armor with his mask raised walks through a spooky forest, his eyes staring straight ahead, trying to ignore his terrifying surroundings. But Reaper turned to him, held up the hourglass, and Reaper's rotten nose, shriveled face was pressed against the skull, and worms and snakes tangled in his hair... Above the dense forest was an empty sky, and under the horseshoes was a barren earth. The knight may have become a spirit, clad in armor against fear and temptation. It's an existential journey through a landscape of dread. In the 20th century, Otto Dix (Otto Dix, a German painter and one of the representatives of New Materialism) saw the face of death described by Dürer on the battlefield of the First World War, and wrote it in his engraving " Recorded in The War.

Dürer, Knight, Death and the Devil, 1513

Although, this exhibition cannot fully reveal Dürer's time or his "material world". But Walker believes, "It's a contact with a recognizable world. Renaissance clocks, antique crossbows, bird decorations have emotional resonance for people." Maybe the real objects are not as vivid as Dürer's performance, but encountering these objects, It makes us feel that although there is an irreparable time distance with Dürer, we can be so close.

Dürer, The Sea Monster, 1498-1501

Note: The exhibition is part of the research project "Dürer's Material World" and will last until March 10, 2024. This article is compiled from "The World of Precisely Printed Medieval Monsters and Savages" by Jonathan Jones of "The Guardian" and "Dürer Changes the Design World" by Nicholas Rowe.

"Dürer's Self-Portrait", 1500, in the collection of the Old Painting Museum in Munich (not exhibited in this exhibition)